Editorial

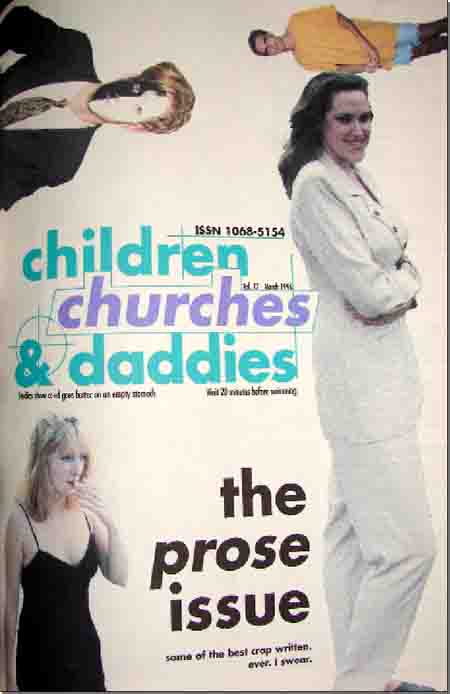

There is so much to discuss that I don’t know where to begin, but a good place is always the cover. The people on the cover are your editorial staff, so now you get a little peek into who makes up these issues (Mike, our cover coordinator, didn’t get us a photo - how ironic...) Which brings us to the inside of this issue - our second prose issue to date. We’ve received so many good stories lately that we thought we’d just put them all (or at least a good number) of them together. So for those of you who like short stories, you’ll really like this issue. There has been a lot going on in the personal lives of the editorial staff here at cc+d, which has made the production of these recent issues a little difficult. My mother and Eugene Peppers’ father were recently diagnosed with cancer - his father is going through chemotherapy after one round of surgery; my mother required three rounds of surgery. But the outlook is good for both Mr. Peppers and Mrs. Kuypers, which makes it a little easier for all of us to work, to say the least. Our thoughts are with you both. AIDS Watch is now a regular part of cc+d, it seems - and there are a bunch of great political and news stories in this issue, too. So relax, read on, but wait 20 minutes before swimming. And enjoy! -Janet Kuypers

lunchtime poll topic

In the Movie Heathers, four snotty high-school women would come up with a weekly question, and poll everyone in the cafeteria for an answer. The called it the Lunchtime Poll Topic, and answers would be funny, bold, interesting - but at least they made you think. We here are Children, Churches and Daddies thought it would be a good idea to foster some discussions - or debates - of our own with a monthly version of the Lunchtime Poll Topic. If you’re interested in being a part of the Lunchtime Poll Topic questioning, email me with your email address, and your answers can be printed here. If you’re interested in responding to a Lunchtime Poll Topic that you’ve seen in print, email or mail us and we may use your letter in the Letter To The Editor section. so, riddle me this, batman: abortion. what do you think? pro-abortion or anti-abortion? pro-life or pro-choice? and what do you think of protests in front of clinics? and... do you think legislation will ever change it back, make it illegal?

Teresa Huminik, Eve Bartlett, Dawn McCallum, Amanda Chaseman and Jack McCallum - at LRPro Pro-Choice. I think protesting in front of clinics is a constitutional right, as long as they don’t interfere with those entering the clinics. The minute the step in front of someone who is entering or chain themselves to the door, they are blocking the other person’s constitutional rights. Potential life should never be given more value than life. And yes, I believe that if we’re not careful and take a more active approach to ensuring a woman’s reproductive rights, abortion could become illegal again. By the way, I don’t notice any of our law makers stepping forward to introduce legislation where men have to have vasecotomies (or however it is spelled). If they can tell a woman what to do with her womb, why can’t they tell a man what to do with his... lower region?

Ted Kusio, Editor. i go with fat elvis.

Ben Whitmer, Writer. certainly i’m anti abortion. i wish we lived in a time and place where abortion didn’t need to be an option. where there were things like health care, food, and educational options open to all. y’know, someplace something like this pretends to be. i am, however, thankful for the debate. there’s nothing to a bring a smile to my face like seeing christians and capitalists howl about the sanctity of life.

Alexandria Rand, Writer. I find it irritating that all the terminology for pro-choice sounds worse than pro-life. They say pro-life is the same as pro-family - does that mean people who believe that women have a right to their own bodies don’t believe in families, in the family unit? No, I’m sure they do - and they probably believe in a healthy, less dysfunctional family than their pro-family counterparts. Does the fact that they are pro-life mean that we as pro-choicers are against life? No, we’re for life - we’re for a life that is taken care of, that is nurtered, that is able to have a chance. That isn’t hated by the parents for spoiling their misspent youth, that isn’t the pawn of parent attempting to get more welfare money. No, we’re for life - the life of the woman, who is alive and independent (unless you talk to the pro-lifers again).

Gary Pool, Free-lance writer and editor, Bloomington, Indiana I am not “pro abortion.” I doubt there are many involved in this emotional debate who would refer to themselves as such. I do, however, believe in a woman’s right to have control over her own body. I am therefore pro choice. I do not think, were I a woman, that I would ever have an abortion, but I am not a woman and therefore will never be faced with that agonizing decision. Though there are many, among the ranks of the so-called “pro-life” movement, who are women, I find it more than a little presumptuous that the debate over a woman’s right to choose an abortion is being, and has been, carried out largely by men. Certainly the most vociferous, and the most violent proponents of the “pro-life” agenda are self-righteously motivated males. I see this quite clearly as a continuation of the centuries old assertion of bodily control and subjugation of women by men. It is indeed sad to imagine abortion. But is it not equally sad to imagine the lives of many thousands of unwanted, uncared for children? Those of the extremist religious right, whose opposition to abortion is by far the shrillest and the most emotionally based, are also among the same groups that oppose AFDC and other welfare and educational programs that benefit poor, often unwed, mothers and their children. Though there is, from time to time, some token support for adoption of unwanted children, these religious zealots spend a good deal more time and money trying to prevent abortion of the fetus than they do the adoption of the unwanted child that results when that fetus reaches maturity and is born into this world. Like other such emotionally charged debates, it is hard to see this one clearly through the clouds of vitriol that surround it. One wonders at times if a reasoned and rational discussion is even possible in the present social and political climate, especially when the leaders of the “pro-life” movement so often encourage their followers to resort to doing violence, even murder, and many of those followers are all to eager to cmply. Of course, as is true everywhere in our society today, the total lack of any kind of responsible political leadership is also a tremendous contributing factor to the rancor and confusion. As long as politicians continue to pander to certain of their constituencies and play games with such hot-button issues, the situation is quite likely to remain the same for the foreseeable future. I do not believe, however, that the Supreme Court, or the Congress, will completely outlaw abortion. But I do feel that we are going to see stricter limitations enacted and upheld, especially on the state level.

Stefani P., Region 1 director, WRL. I work with Right to Life, and I have to put in my two pennies on this. I am pro-life, in all instances except when a womans life in in danger. I also feel that it is NOT a womans body. The baby has its own blood stream (even blood type) which never mixes with the mothers, its own DNA code, its own brain and its own sense of awareness....this indicates that it is its own person, NOT a part of the mothers body. I am pro-woman AND pro-life.

Gabriel Athens, Writer They talk about the rights of the unborn child, but they forget about the rights of the already-born woman, the woman who would have to give up the remainder of her life to take care of that child, or at least the next year if she were to have an adoption. And there are waiting lists for babies - but they’re for newborns, white ones at that. Let me see these republicans say they’ll take care of all the black welfare crack babies in America and then I’ll believe that adoption in our country is a feasible solution.

Andy Lowry, Editor, Fuel (alowry@mcs.com) I’m voraciously pro-choice. I don’t care what people’s opinions are on the subject, but keep your hands off my body. And the fact that the rich old white men are making these laws are another whole topic. Plus, aborions WILL continue even if they are illegal, it’s proven. Also, what about all those babies (esp. of color) waiting to be adopted (30,000 in Chicago/Cook County alone).

Shannon Peppers, Writer This shouldn’t be a political issue. I’ve worked with women who have been raped, and if I ever had to tell a woman pregnant from a rapist that she had to keep what this animal did to her... God, I can’t even imagine it. Imagine having this most traumatic experience happen to you, something that’s going to take a very long time to recover from, something that alters your life and you’ll never forget, that you’ll always have to live with. Then imagine being told that you have to give birth to and raise this monster’s child, that you have no choice, and that every time you look at this child, you’ll see the eyes of the man who raped you. Imagine that. Just imagine it. If that’s the way it is supposed to be, then that’s a clear sign that we don’t care for the women living in this country. And if we can’t do that, how are we supposed to care for the unborn?

Cheryl Townsend, Editor, Impetus

BLESSED ARE THE PRO-CHOICE CHILDREN

Garbage pails make uncomfortable bassinets and belt buckles leave strange tattoos Little girls can only stretch so far for daddy before their time Arms are odd ashtrays Closets are dark and basements as cold Cocaine is hard to get when you can’t walk yet Flesh bleeds and bones break Murder more justifiable before they have a chance

I’m begginig to favor mandatory sterilization.. 1 death to a living child from abuse...you don’t get another chance. Pro-choice means you control your own body...not that of the child you give birth to (beyond NORMAL child-rearing.) All those Pro-lifer’s who carry a fetus with them to a protest (no respect for it OUTSIDE the womb, eh?) should be countered with police photos of children who have been killed by the hands of their parents. Let them see what they are fighting for.

MATTER OF

I don’t force you to raise it so don’t you force me to bear it

And where are they when you need them??? Oh well, MY job is done, The child is born... It’s outta my hands now. Hrumph! What would they do if everyone they scared away from an abortion clinic left their children on their doorsteps after they gave birth to it...unwanted... call the cops?

CONNECTION

A child was found in a dumpster this morning still breathing in harmony with 117 anti-abortionists demonstrating outside a clinics walls that a fetus has a right to life

I agree w/ Gary Pool’s response. I am not pro-abortion... I am pro- choice/pro-life. Life is a gift, don’t be an indian-giver and take it away as soon as you give it. NO ONE SHOULD HAVE TO BEAR AN UNWANTED CHILD. NO CHILD SHOULD HAVE TO BE BORN UNWANTED! When will pro-lifers realize they are not saving anything, but actually jeapordizing lives? Don’t they read the newspapers? Aren’t they appalled by the number of children killed every day by their own parents? Is it worth the hours or days or weeks or months or maybe years they survived, unwanted, just to die such a horrendous death? Possibly tortured every day they did live? I think my pro-choice stand point is more for the children than for the woman (tho I am 100% for the right to choose)... I do not condone abortion as a means of birth control. I wish more mothers would give their (unwanted) children up for adoption. I wish that adoption were easier. I wish there were more counselling and options available to women who are unaware that they even exist (options)... Nine months is a long time to fester. anyway, I can (and usually do) go on for hours... maybe I’ll do this in installments..but on-line time is costly, so I’ll end my say with a God Bless you Gary Pool... may you multpily in spirit worldwide!

Joe Speer, Editor. Dear Janet, i like to hear different opinions. for example, i can say: let the contentious croats, serbs, and bosnians learn to duck walk. We can’t stop people in America from killing each other, how can we stop the killing overseas? We can’t. If the U.S. military has to get involved, let them sell guns and cigarettes to the combatants. every combat zone provides a market for U.S. arms. Bosnia is not my problem. discontinue news coverage. do like the police do in America when there is a riot in the ghetto, like in south central LA, cordon the area off and let them slug it out. but you asked about abortion. the decision to abort a fetus is the problem of a pregnant female. Men do not get pregnant so men should have no say so in the decision making process. abortion should be a legal option. abortion is like a car accident, it can and should be avoided. we take drivers training and drive sober etc to avoid accidents. we need to educate couples on the techniques of how to avoid unwanted pregnancy. if a pregnancy occurs, then a woman needs to know all the ways to deal with it; let grandma raise it, sell it on the black market, adoption, etc. giving birth to a child is not the real problem, to nurture a child and provide for their education and love them and raise them to be creative members of society, that is the real concern. reproduction for the sake of reproduction is not the issue. rabbits and cockroaches reproduce freely. so what do you get? more rabbits and cockroaches. anyway, thanks for asking.

short stories

The Electric Chair, by Lance C. Burri

“Dinner!” Billy heard his father’s voice, muffled as it reached his room through the floor. He wasn’t hungry, but put down the comic he was reading and went out into the hallway anyway. He could see well enough by the light from the living room on the stairway walls, so he didn’t bother turning the hall light on. The door to his sister’s room was still closed, and Billy pressed his ear against it as he went by. Sometimes he could overhear her talking on the phone. He couldn’t hear anything this time, though, and went on down the stairs. “Dinner!” Billy heard his father’s voice, muffled as it reached his room through the floor. He wasn’t hungry, but put down the comic he was reading and went out into the hallway anyway. He could see well enough by the light from the living room on the stairway walls, so he didn’t bother turning the hall light on. The door to his sister’s room was still closed, and Billy pressed his ear against it as he went by. Sometimes he could overhear her talking on the phone. He couldn’t hear anything this time, though, and went on down the stairs.

His father had set up TV trays, one in front of his chair and two more in front of the couch. A second chair sat opposite his father’s, and a coffee table which had been moved to accommodate the trays. A polished wooden plaque on the wall above the television read “Home of The Joneses” in lavender paint. “Sorry dinner’s so late,” said his father. Billy jumped onto the couch, sliding his feet underneath the tray. The lasagna was still steaming. His father had set up TV trays, one in front of his chair and two more in front of the couch. A second chair sat opposite his father’s, and a coffee table which had been moved to accommodate the trays. A polished wooden plaque on the wall above the television read “Home of The Joneses” in lavender paint. “Sorry dinner’s so late,” said his father. Billy jumped onto the couch, sliding his feet underneath the tray. The lasagna was still steaming.

“S’okay,” he answered. “I had a snack after school.”They watched Pat Sajak introduce the contestants. Billy drank milk from a plastic cup, waiting for the lasagna to cool. “S’okay,” he answered. “I had a snack after school.”They watched Pat Sajak introduce the contestants. Billy drank milk from a plastic cup, waiting for the lasagna to cool.

“Where’s your sister?” “Where’s your sister?”

“Her room, I guess.” Billy’s father called upstairs again, then moved his tray, grumbling to himself, when there was no response. He rose and walked to the stairs. “Her room, I guess.” Billy’s father called upstairs again, then moved his tray, grumbling to himself, when there was no response. He rose and walked to the stairs.

Billy blew on a small fork-full, testing it gently with his tongue before eating it. He could hear his father’s knock upstairs, then his voice, but couldn’t make out what he was saying. His heavy footsteps thudded down the hall, and a minute later the middle-aged man walked back into the living room. He went to the third tray and picked up the plate. “You want any of this?” he asked, his voice hard-edged. When Billy shook his head his father scraped most of its contents onto his own plate, then picked up the unused cup and carried them into the kitchen. Billy heard the milk go down the drain. Billy blew on a small fork-full, testing it gently with his tongue before eating it. He could hear his father’s knock upstairs, then his voice, but couldn’t make out what he was saying. His heavy footsteps thudded down the hall, and a minute later the middle-aged man walked back into the living room. He went to the third tray and picked up the plate. “You want any of this?” he asked, his voice hard-edged. When Billy shook his head his father scraped most of its contents onto his own plate, then picked up the unused cup and carried them into the kitchen. Billy heard the milk go down the drain.

His father was pulling his shirttails out of his pants when he came back in. His tie had already come off, draped over the briefcase he had left near the front door. The snap would be next. Billy’s father was always saying he needed new pants, and his mother always said that it was cheaper to lose weight. He pulled the tray up to his lap and began to eat in earnest, barely looking at America’s favorite game show. His father was pulling his shirttails out of his pants when he came back in. His tie had already come off, draped over the briefcase he had left near the front door. The snap would be next. Billy’s father was always saying he needed new pants, and his mother always said that it was cheaper to lose weight. He pulled the tray up to his lap and began to eat in earnest, barely looking at America’s favorite game show.

Twenty minutes later Billy carefully slid under his tray, ducking his head until he knew he was clear. His father was already finished and had pushed his tray to one side so that he could kick the footrest out of his chair. His 7-up can was propped against the inside of his leg. Twenty minutes later Billy carefully slid under his tray, ducking his head until he knew he was clear. His father was already finished and had pushed his tray to one side so that he could kick the footrest out of his chair. His 7-up can was propped against the inside of his leg.

“Done, Billy?” he asked, glancing at the eight-year old. “Done, Billy?” he asked, glancing at the eight-year old.

“Yeah,” the boy answered, trotting away from his half-empty plate and around the end of the couch. He headed for the stairs, but stopped as the front door opened. His mother followed the door as she pushed it, holding a briefcase and a purse awkwardly in one hand, bracing the door with the same arm and jiggling the key out of the lock with the other. That done, she stepped in and dropped her things. “Yeah,” the boy answered, trotting away from his half-empty plate and around the end of the couch. He headed for the stairs, but stopped as the front door opened. His mother followed the door as she pushed it, holding a briefcase and a purse awkwardly in one hand, bracing the door with the same arm and jiggling the key out of the lock with the other. That done, she stepped in and dropped her things.

“Hi, sweetie,” she said to Billy as she removed her coat. “Hi, sweetie,” she said to Billy as she removed her coat.

“Hi, Mom. ‘Nother late day, huh?” “Hi, Mom. ‘Nother late day, huh?”

His mother smiled apologetically. “Yeah. I’m afraid so.” She closed the door and walked into the room. Billy’s father turned around in his chair and acknowledged his wife’s entrance. “Hi, hon,” she said in reply. “You learn a lot in school today, Billy?” His mother smiled apologetically. “Yeah. I’m afraid so.” She closed the door and walked into the room. Billy’s father turned around in his chair and acknowledged his wife’s entrance. “Hi, hon,” she said in reply. “You learn a lot in school today, Billy?”

“Naw,” he said. “Jeff hadda go to the office for yelling at the teacher, though.” “Naw,” he said. “Jeff hadda go to the office for yelling at the teacher, though.”

“Great,” she said, a sardonic hint in her voice. “Any dinner left?” she asked her husband. “Great,” she said, a sardonic hint in her voice. “Any dinner left?” she asked her husband.

He shook his head. “I just cooked up that frozen lasagna,” he said. She nodded, kicking off her shoes. He shook his head. “I just cooked up that frozen lasagna,” he said. She nodded, kicking off her shoes.

Billy headed upstairs. Halfway up, he heard his sister’s door closing, and she passed him as he reached the top. “Watch out,” she said, nudging him over with her elbow. Tanya was fifteen, with straight blondish-brown hair like her mother’s. She was wearing a pair of blue jeans, ripped at the knees, and a tank top cut off at the middle. Billy headed upstairs. Halfway up, he heard his sister’s door closing, and she passed him as he reached the top. “Watch out,” she said, nudging him over with her elbow. Tanya was fifteen, with straight blondish-brown hair like her mother’s. She was wearing a pair of blue jeans, ripped at the knees, and a tank top cut off at the middle.

Billy sat cross-legged at the top of the stairs and peered through the banister, where he could see nearly the entire living room.“Where are you going,” his father asked as she came down the stairs. Billy sat cross-legged at the top of the stairs and peered through the banister, where he could see nearly the entire living room.“Where are you going,” his father asked as she came down the stairs.

Tanya pulled a windbreaker out of the closet. “To Laurie’s,” she answered. Tanya pulled a windbreaker out of the closet. “To Laurie’s,” she answered.

“It’s getting kind of late,” her mother said, standing by the couch. “It’s getting kind of late,” her mother said, standing by the couch.

“How come you’re going to Laurie’s?” “How come you’re going to Laurie’s?”

“I won’t be gone long, Mom.” “I won’t be gone long, Mom.”

“Is anyone else going to be there?” she asked. “Is anyone else going to be there?” she asked.

Tanya finished pulling on her jacket and zipped it, keeping her eyes lowered to her business. “I don’t know, Mom,” she said. Tanya finished pulling on her jacket and zipped it, keeping her eyes lowered to her business. “I don’t know, Mom,” she said.

“Kevin isn’t going to be there, is he?” “Kevin isn’t going to be there, is he?”

Tanya slammed the closet door and turned angrily toward her mother, her hands planted firmly on her hips. “Are you ever going to give me a break, Mom?” she asked. Billy pressed his face up to the banister, not wanting to miss the argument he knew was coming. Tanya slammed the closet door and turned angrily toward her mother, her hands planted firmly on her hips. “Are you ever going to give me a break, Mom?” she asked. Billy pressed his face up to the banister, not wanting to miss the argument he knew was coming.

“I’m just trying to look out for you...” “I’m just trying to look out for you...”

“Well I can look out for myself!” Tanya interrupted, her voice rising into a screech. “Well I can look out for myself!” Tanya interrupted, her voice rising into a screech.

“Honey,” her mother continued, her own voice hardening, “Kevin is not the kind of guy we think you should be dating.”

“Oh, Jesus Christ,” Tanya spat, turning around dismissively. “Oh, Jesus Christ,” Tanya spat, turning around dismissively.

“Hey, you watch your mouth,” her father called, turning around in his chair. “And you listen to your mother, young lady.” “Hey, you watch your mouth,” her father called, turning around in his chair. “And you listen to your mother, young lady.”

Tanya just shook her head in apparent frustration and reached for the door. Tanya just shook her head in apparent frustration and reached for the door.

“Hold on, Tanya,” her mother said, taking a few steps toward her and assuming a stern demeanor. “Have you even done your homework yet?” “Hold on, Tanya,” her mother said, taking a few steps toward her and assuming a stern demeanor. “Have you even done your homework yet?”

Tanya only looked back for a moment. “Christ, Mom, will you get off my case!” She walked out, slamming the door behind her. Tanya only looked back for a moment. “Christ, Mom, will you get off my case!” She walked out, slamming the door behind her.

Her mother watched the door for a few seconds before dropping her hands in futility and turning back to the living room. She walked around the living room set, dropped herself into the other easy chair across from her husband. “That girl just doesn’t want to listen anymore,” she said. Her mother watched the door for a few seconds before dropping her hands in futility and turning back to the living room. She walked around the living room set, dropped herself into the other easy chair across from her husband. “That girl just doesn’t want to listen anymore,” she said.

Her husband shrugged. “What’re you gonna do? Kids are like that all over the place these days.” He lifted the can to his lips, forgetting that it was already empty. He reached out and placed it on the coffee table, disappointed. “Maybe we should ground her, you know?”His wife was shaking her head. “Maybe we should see a counselor or something.” Her husband shrugged. “What’re you gonna do? Kids are like that all over the place these days.” He lifted the can to his lips, forgetting that it was already empty. He reached out and placed it on the coffee table, disappointed. “Maybe we should ground her, you know?”His wife was shaking her head. “Maybe we should see a counselor or something.”

She pushed the footrest out of her chair and leaned back with her eyes closed. The man sighed out loud and focused his attention on the television. She pushed the footrest out of her chair and leaned back with her eyes closed. The man sighed out loud and focused his attention on the television.

“I’m so tired,” said his wife. “I think I’ll just fall asleep right here.”“Seinfeld’s on later,” he answered. “I’m so tired,” said his wife. “I think I’ll just fall asleep right here.”“Seinfeld’s on later,” he answered.

“Hmmm,” she considered. “Maybe you could tape it?” “Hmmm,” she considered. “Maybe you could tape it?”

“Sure. We gotta tape?” “Sure. We gotta tape?”

She shrugged and rolled her shoulders, pressing deeper into the chair. She shrugged and rolled her shoulders, pressing deeper into the chair.

Billy stood up quietly, the excitement apparently over. He had hoped to hear how his parents were going to punish Tanya, but it looked like they weren’t going to talk about it anymore. He walked into their bedroom and switched on the television there. The Simpsons would be on in a few minutes. Billy stood up quietly, the excitement apparently over. He had hoped to hear how his parents were going to punish Tanya, but it looked like they weren’t going to talk about it anymore. He walked into their bedroom and switched on the television there. The Simpsons would be on in a few minutes.

A Bad Day In Paradise, by d. v. aldrich

There are two things I hate in life - war and Elvis Presley look-alikes; other, less serious, problems seem to fall into one of those gray areas, very much like the boredom I’m experiencing right now. I was banished from my bedroom tonight for reasons I don’t understand, and I’ve already spent my inheritance dialing 1-900-PSYCHIC. So, unless I want to play with my wife’s collection of Barbie dolls or harass the cat again, I need to find something else to occupy my time. Perhaps the best thing for me to do is to take a few minutes an reflect on what got me into this mess in the first place. There are two things I hate in life - war and Elvis Presley look-alikes; other, less serious, problems seem to fall into one of those gray areas, very much like the boredom I’m experiencing right now. I was banished from my bedroom tonight for reasons I don’t understand, and I’ve already spent my inheritance dialing 1-900-PSYCHIC. So, unless I want to play with my wife’s collection of Barbie dolls or harass the cat again, I need to find something else to occupy my time. Perhaps the best thing for me to do is to take a few minutes an reflect on what got me into this mess in the first place.

Last evening my wife and I stopped at a cafe, alongside the Gulf of Mexico, trying to kill about an hour before, hopefully, enjoying a beautiful sunset off one of Florida’s beaches. “Will that be all?” the waiter questioned us in snippy tones after we had ordered only shrimp cocktails and a couple of beers. Speaking politically correct, I’m not financially challenged, but I thought the price of a shrimp cocktail was exorbitant. “Let’s see, six dozen live shrimp for $6.00 at a bait shop vs. one dozen dead shrimp for $8.00 at this restaurant, there’s something wrong with this picture,” I complained to my wife. Last evening my wife and I stopped at a cafe, alongside the Gulf of Mexico, trying to kill about an hour before, hopefully, enjoying a beautiful sunset off one of Florida’s beaches. “Will that be all?” the waiter questioned us in snippy tones after we had ordered only shrimp cocktails and a couple of beers. Speaking politically correct, I’m not financially challenged, but I thought the price of a shrimp cocktail was exorbitant. “Let’s see, six dozen live shrimp for $6.00 at a bait shop vs. one dozen dead shrimp for $8.00 at this restaurant, there’s something wrong with this picture,” I complained to my wife.

“We are paying for the atmosphere and the cooking of the shrimp,” she cordially offered. “Okay, I’ll buy that,” I responded, then observed the tattooed biker chick sitting to my left, the cigarette butts on the floor, and our waiter’s look of anger when I requested he bring us the urn since we were obviously paying for the shrimp’s cremation rites. “We are paying for the atmosphere and the cooking of the shrimp,” she cordially offered. “Okay, I’ll buy that,” I responded, then observed the tattooed biker chick sitting to my left, the cigarette butts on the floor, and our waiter’s look of anger when I requested he bring us the urn since we were obviously paying for the shrimp’s cremation rites.

Well, that was yesterday, and today would be a new day. “Let’s go back over to the beach this morning and grab a few rays,” I suggested to my wife, hoping to make up for the hissy fit I’d thrown last night. “Sounds good to me,” she replied, and we were off to the beach. Well, that was yesterday, and today would be a new day. “Let’s go back over to the beach this morning and grab a few rays,” I suggested to my wife, hoping to make up for the hissy fit I’d thrown last night. “Sounds good to me,” she replied, and we were off to the beach.

We always have a great time at the beach, except for one thing - quarters needed for the stupid parking meters; I never have enough, and today was no exception. Even though I had robbed $3.00 worth of quarters out of my daughter’s lunch money, I don’t think the sun’s rays ever penetrated the sun blocker we were using before we ran out of quarters. Deciding the meter maid probably wouldn’t believe our claim of diplomatic immunity, we packed up our beach supplies and headed home. We always have a great time at the beach, except for one thing - quarters needed for the stupid parking meters; I never have enough, and today was no exception. Even though I had robbed $3.00 worth of quarters out of my daughter’s lunch money, I don’t think the sun’s rays ever penetrated the sun blocker we were using before we ran out of quarters. Deciding the meter maid probably wouldn’t believe our claim of diplomatic immunity, we packed up our beach supplies and headed home.

“The toll road is bumper to bumper today,” my wife commented after we had been sitting in traffic form some time. While patiently awaiting our turn to donate our share of money to the governor’s swimming pool fund, my only two thoughts were I hoped my license tags wouldn’t expire and prayed my bladder wouldn’t burst before finding relief in my bathroom at home.Having no change, I offered the tolltaker the sum of my weekly allowance to which he tersely responded, “Do you have anything smaller than a $20.00 bill?” “I have a $15.00 bill from our veterinarian,” I came back with a smirky grin on my face. You know, I’m pretty sure the tolltaker signaled me I was ‘number one’ on his list of favorite people. How kind, I’ll have to send him a Christmas card this year. “The toll road is bumper to bumper today,” my wife commented after we had been sitting in traffic form some time. While patiently awaiting our turn to donate our share of money to the governor’s swimming pool fund, my only two thoughts were I hoped my license tags wouldn’t expire and prayed my bladder wouldn’t burst before finding relief in my bathroom at home.Having no change, I offered the tolltaker the sum of my weekly allowance to which he tersely responded, “Do you have anything smaller than a $20.00 bill?” “I have a $15.00 bill from our veterinarian,” I came back with a smirky grin on my face. You know, I’m pretty sure the tolltaker signaled me I was ‘number one’ on his list of favorite people. How kind, I’ll have to send him a Christmas card this year.

After checking my tires and my wife’s yelling out the window, “You’re gonna get arrested for indecent exposure!”, we stopped by the supermarket on our way home. After checking my tires and my wife’s yelling out the window, “You’re gonna get arrested for indecent exposure!”, we stopped by the supermarket on our way home.

“Paper or plastic?” the zit-faced bag boy asked. Having stood in the check-out line long enough to determine the cashier’s name tag would still read Anna spelled backwards and hungry enough to enjoy possum noodle soup, I boldly stated, “Forget the paper or plastic crap! Bring us a can opener; we’re going to eat right here!” I really wish I hadn’t made such a rude remark. I just know my wife is not going to cook for a week, and you can bet Anna, the cashier, will make confetti out of my check cashing card the next time I’m in her check-out line. “Paper or plastic?” the zit-faced bag boy asked. Having stood in the check-out line long enough to determine the cashier’s name tag would still read Anna spelled backwards and hungry enough to enjoy possum noodle soup, I boldly stated, “Forget the paper or plastic crap! Bring us a can opener; we’re going to eat right here!” I really wish I hadn’t made such a rude remark. I just know my wife is not going to cook for a week, and you can bet Anna, the cashier, will make confetti out of my check cashing card the next time I’m in her check-out line.

Okay, so we finally made it home, and I immediately opened the mail. “Look, honey, you’ve won ten million dollars in the magazine sweepstakes,” I joked and tossed Ed McMahon’s personalized, heart gripping letter to her. I have a message for Ed’s cronies should they ever bring a ten million dollar check into my neighborhood, “May the force be with you, the entire police force, that is.”In hopes of getting my wife in a better mood, I spent the entire afternoon replacing some broken wall tiles in our bathroom, which turned out to be a disaster. I admit there was no excuse for my not warning my wife I had dripped some glue on the toilet seat before she sat down. Okay, so we finally made it home, and I immediately opened the mail. “Look, honey, you’ve won ten million dollars in the magazine sweepstakes,” I joked and tossed Ed McMahon’s personalized, heart gripping letter to her. I have a message for Ed’s cronies should they ever bring a ten million dollar check into my neighborhood, “May the force be with you, the entire police force, that is.”In hopes of getting my wife in a better mood, I spent the entire afternoon replacing some broken wall tiles in our bathroom, which turned out to be a disaster. I admit there was no excuse for my not warning my wife I had dripped some glue on the toilet seat before she sat down.

I was still alive by nightfall and thought the best thing for me to do was to join my wife in watching a little television. Since there was no dinner served at our house tonight, which I’m hoping is only a temporary problem, I grabbed a few snacks and caught up with her in the living room. I was still alive by nightfall and thought the best thing for me to do was to join my wife in watching a little television. Since there was no dinner served at our house tonight, which I’m hoping is only a temporary problem, I grabbed a few snacks and caught up with her in the living room.

I flipped on the TV and surfed through all the stations, finding only sex and violence on nearly all the programs. “Let’s cut to the chase and cut down on our viewing time,” I suggested, and we began watching the national news. I flipped on the TV and surfed through all the stations, finding only sex and violence on nearly all the programs. “Let’s cut to the chase and cut down on our viewing time,” I suggested, and we began watching the national news.

I’ve noticed my wife goes into some sort of trance whenever Peter Jennings is on television. I wonder if he ever glued his wife to the toilet seat? Anyway, Mr. Goodlooks took a break and I heard the Hollywood reporter say, “More nude photos of Madonna to be released soon.” For whatever reason, I suddenly remembered I hadn’t fed the dog. I’ve noticed my wife goes into some sort of trance whenever Peter Jennings is on television. I wonder if he ever glued his wife to the toilet seat? Anyway, Mr. Goodlooks took a break and I heard the Hollywood reporter say, “More nude photos of Madonna to be released soon.” For whatever reason, I suddenly remembered I hadn’t fed the dog.

“Here we go again,” I thought when I noticed three cans of dog food costs about the same as one hamburger at the fast food joint. You don’t suppose? No, they wouldn’t do that, would they?Bed time finally arrived, and my last thoughts before retiring for the night were maybe I’m too old fashioned, and maybe I just need to get with the plan. “I can fix that,” I said to myself, thinking I’m not over the hill yet. “Here we go again,” I thought when I noticed three cans of dog food costs about the same as one hamburger at the fast food joint. You don’t suppose? No, they wouldn’t do that, would they?Bed time finally arrived, and my last thoughts before retiring for the night were maybe I’m too old fashioned, and maybe I just need to get with the plan. “I can fix that,” I said to myself, thinking I’m not over the hill yet.

I splashed on my best designer fragrance, Old Spice, and, “yo, ho, ho” I jumped into bed. I snuggled up next to my wife and softly whispered into her ear, “Honey, I think you’re so bitchin’. Wanna tread back over to the beach tomorrow and knock the heads off a couple of brewskis?” I splashed on my best designer fragrance, Old Spice, and, “yo, ho, ho” I jumped into bed. I snuggled up next to my wife and softly whispered into her ear, “Honey, I think you’re so bitchin’. Wanna tread back over to the beach tomorrow and knock the heads off a couple of brewskis?”

As you’ve probably guessed, we won’t be going to the beach tomorrow. I’m going to be spending my time shopping for a convertible sofa. This couch I’m now forced to sleep on leaves a lot to be desired, which is the exact same phrasing my wife uses when describing my attitude since I found out postage rates have gone up. Goodnight. As you’ve probably guessed, we won’t be going to the beach tomorrow. I’m going to be spending my time shopping for a convertible sofa. This couch I’m now forced to sleep on leaves a lot to be desired, which is the exact same phrasing my wife uses when describing my attitude since I found out postage rates have gone up. Goodnight.

Screams in America, by David Caylor

I wasn’t sure when it happened, but an old Cambodian lady had moved in across the hall. I had seen The Killing Fields six times, so I knew she was Cambodian. At first, I felt bad for her. She had come thousands of miles and landed in a one-room efficiency. There she was, packed in with cockroaches. There had to be 100,000 roaches in the building. I wasn’t sure when it happened, but an old Cambodian lady had moved in across the hall. I had seen The Killing Fields six times, so I knew she was Cambodian. At first, I felt bad for her. She had come thousands of miles and landed in a one-room efficiency. There she was, packed in with cockroaches. There had to be 100,000 roaches in the building.

My address was 809 1/2 Second Avenue, Apartment 127. She was in apartment 128. The longer the address the worse the place. Nice places have addresses like 29 North Street. My address was 809 1/2 Second Avenue, Apartment 127. She was in apartment 128. The longer the address the worse the place. Nice places have addresses like 29 North Street.

I first saw her one afternoon as I cam back from work. It was warm, ninety-three degrees. The walk home had beaten me. I only wanted to get inside, turn on the air conditioner and read the afternoon newspaper. I went through the buildings’ front door, down a short flight of steps and saw her. She was standing in the hallway leaning up against the door. She looked like an old yellow whore working the building. I assumed I’d be able to walk right past her. As I got closer, she took notice and straightened up. I got out my key and thought I was home. I first saw her one afternoon as I cam back from work. It was warm, ninety-three degrees. The walk home had beaten me. I only wanted to get inside, turn on the air conditioner and read the afternoon newspaper. I went through the buildings’ front door, down a short flight of steps and saw her. She was standing in the hallway leaning up against the door. She looked like an old yellow whore working the building. I assumed I’d be able to walk right past her. As I got closer, she took notice and straightened up. I got out my key and thought I was home.

“Excuse me, sir,” she said. she pulled out a map of the downtown area. It was actually a photocopy of a map. “Do you know where is Land-gon?” I pointed Langdon Street out on the map. It was as hot in the hallway as it was outside. I wasn’t in the mood.“If I go there will I be a Doctor?” she asked smiling up at me. Half of her teeth were rotten. “Excuse me, sir,” she said. she pulled out a map of the downtown area. It was actually a photocopy of a map. “Do you know where is Land-gon?” I pointed Langdon Street out on the map. It was as hot in the hallway as it was outside. I wasn’t in the mood.“If I go there will I be a Doctor?” she asked smiling up at me. Half of her teeth were rotten.

“I don’t know if there is a doctor on that street or not.” I turned toward my door and she followed me. She pointed down to Gorham Street. “I don’t know if there is a doctor on that street or not.” I turned toward my door and she followed me. She pointed down to Gorham Street.

“What street is this?” Her breath was terrible. “What street is this?” Her breath was terrible.

“Gorham.” “Gorham.”

“If I go here and to here,” she said moving her finger down Gorham to McKinley Boulevard, “will I be a Master?” I had no idea what she was talking about. She continued, “If I go here and here and here, I’ll be a Doctor?” She seemed to be referencing academic degrees. “If I go here and to here,” she said moving her finger down Gorham to McKinley Boulevard, “will I be a Master?” I had no idea what she was talking about. She continued, “If I go here and here and here, I’ll be a Doctor?” She seemed to be referencing academic degrees.

“I really don’t know, lady.” I finally got inside and turned on the air conditioning. “I really don’t know, lady.” I finally got inside and turned on the air conditioning.

The next day wasn’t as bad. She was standing out in the hallway again, but our conversation was brief. The next day wasn’t as bad. She was standing out in the hallway again, but our conversation was brief.

“Where do you work?” she asked. “Where do you work?” she asked.

“At a law firm,” I said. “At a law firm,” I said.

“You’re already out of law school?” I was surprised she even knew there was such a thing as law school. “You’re already out of law school?” I was surprised she even knew there was such a thing as law school.

“No, I work for the lawyers.” I got past her and went inside. I had a horrible apartment. It was one room and a small shower. The walls were uncovered brick and the carpet was a worn out brown. I was constantly tearing pictures out of magazines to cover the brick. “No, I work for the lawyers.” I got past her and went inside. I had a horrible apartment. It was one room and a small shower. The walls were uncovered brick and the carpet was a worn out brown. I was constantly tearing pictures out of magazines to cover the brick.

There wasn’t anything else I could do. The place was so small that I had started buying the smallest versions of things. I had a coffee machine that would only make two cups at a time and an ironing board with three inch legs. I used a little toothbrush and those miniature bottles of shampoo. The smallness of everything made me feel like King Kong as I walked around the place. There wasn’t anything else I could do. The place was so small that I had started buying the smallest versions of things. I had a coffee machine that would only make two cups at a time and an ironing board with three inch legs. I used a little toothbrush and those miniature bottles of shampoo. The smallness of everything made me feel like King Kong as I walked around the place.

A few hours after talking to her there was a knock. I walked to the door and looked out the peephole. Her wrinkled face stared back at me. The radio was on, so she knew I was there. I looked through the hole for a minute. She stood and stood and stood. Finally, I went back and sat on my mattress. She knocked a few more times and I ignored her. A few hours after talking to her there was a knock. I walked to the door and looked out the peephole. Her wrinkled face stared back at me. The radio was on, so she knew I was there. I looked through the hole for a minute. She stood and stood and stood. Finally, I went back and sat on my mattress. She knocked a few more times and I ignored her.

The next day I grabbed a bag of trash to toss out and snuck out past her. I got to work, flipped through some spreadsheets and forgot about her. The next day I grabbed a bag of trash to toss out and snuck out past her. I got to work, flipped through some spreadsheets and forgot about her.

It hadn’t cooled off. It was ninety-one at 5:00 p.m. My walk home was five blocks, a little up hill. I was about halfway home when she came to mind. I turned a corner, went into the building and checked my mail. There was nothing but advertisements addressed to STUDENT/OCCUPANT. I keyed the main door and went down the hallway. My room was at the end. It hadn’t cooled off. It was ninety-one at 5:00 p.m. My walk home was five blocks, a little up hill. I was about halfway home when she came to mind. I turned a corner, went into the building and checked my mail. There was nothing but advertisements addressed to STUDENT/OCCUPANT. I keyed the main door and went down the hallway. My room was at the end.

I could already see her, a dark little figure with no shape. I became convinced that she was waiting specifically for me. There was no way around her. I could already see her, a dark little figure with no shape. I became convinced that she was waiting specifically for me. There was no way around her.

“Sir, what does this mean?” She had the newspaper and was pointing at the legal notices. There were tiny paragraphs about people requesting zoning changes and the county was taking bids on truck equipment. “What does this mean?” she smiled as she asked again.“They’re to let people know what is going on,” I said. She pointed down to a specific section. “Sir, what does this mean?” She had the newspaper and was pointing at the legal notices. There were tiny paragraphs about people requesting zoning changes and the county was taking bids on truck equipment. “What does this mean?” she smiled as she asked again.“They’re to let people know what is going on,” I said. She pointed down to a specific section.

“Tom Crawford, owner of property located at 2218 Seminole Hwy., requests a rear yard variance to construct an addition onto his home.” “Tom Crawford, owner of property located at 2218 Seminole Hwy., requests a rear yard variance to construct an addition onto his home.”

I tried to explain that someone wanted to add onto his house and needed permission. I tried to explain that someone wanted to add onto his house and needed permission.

“What does this mean?” she asked again, pointing to ‘construct and addition’. “What does this mean?” she asked again, pointing to ‘construct and addition’.

“Make his house bigger.” I could see she didn’t understand. “Make his house bigger.” I could see she didn’t understand.

“What does this mean? Where is it?” I had no choice but to turn away from her. I went inside and turned on the television and air conditioning, as usual. “What does this mean? Where is it?” I had no choice but to turn away from her. I went inside and turned on the television and air conditioning, as usual.

This was crazy. I was her best friend in America. There were hundreds of rooms in the building and each room had one or two people in it. Still, she was the only person I ever saw. Once in a while I’d hear people shouting at each other or a dog barking, but that was it. This was crazy. I was her best friend in America. There were hundreds of rooms in the building and each room had one or two people in it. Still, she was the only person I ever saw. Once in a while I’d hear people shouting at each other or a dog barking, but that was it.

It was Friday and after it got dark I wanted to go get some supplies. It was Friday and after it got dark I wanted to go get some supplies.

I checked the hallway before leaving. It was clear. I did most of my shopping at Bucky’s Corner Market. It was a little place that had one of everything in stock and was a popular even thought the prices were high. I picked up two six packs, a magazine and a $2.39 bag of pistachios. It was a few blocks from the store to home. The streets were filled with cars. Everyone was going out to the bars and clubs. I got to my building. If she tried to stop me, I would ignore her completely. I walked as quickly as possible. My paper bag was rustling. I imagined her sitting in her apartment and hearing me coming down the hall. She’d jump up, run out and start with more ridiculous questions. Maybe she would have a picture of some stranger and demand I tell her who it was. I checked the hallway before leaving. It was clear. I did most of my shopping at Bucky’s Corner Market. It was a little place that had one of everything in stock and was a popular even thought the prices were high. I picked up two six packs, a magazine and a $2.39 bag of pistachios. It was a few blocks from the store to home. The streets were filled with cars. Everyone was going out to the bars and clubs. I got to my building. If she tried to stop me, I would ignore her completely. I walked as quickly as possible. My paper bag was rustling. I imagined her sitting in her apartment and hearing me coming down the hall. She’d jump up, run out and start with more ridiculous questions. Maybe she would have a picture of some stranger and demand I tell her who it was.

“Who is this? Who is this? Where are they?”None of this happened. I got into my room and started my weekend.Monday morning I bagged some more trash, showered and got dressed for work. The law firm required us to be well dressed. I picked out a black and red tie and a white shirt. I opened the door to leave and she was already standing there. She was holding a bag of something as if she was moving in with me. She looked ugly and insane. It was about seven in the morning and I wasn’t fully awake yet. I thought I might be dreaming. I decided to scream. “Who is this? Who is this? Where are they?”None of this happened. I got into my room and started my weekend.Monday morning I bagged some more trash, showered and got dressed for work. The law firm required us to be well dressed. I picked out a black and red tie and a white shirt. I opened the door to leave and she was already standing there. She was holding a bag of something as if she was moving in with me. She looked ugly and insane. It was about seven in the morning and I wasn’t fully awake yet. I thought I might be dreaming. I decided to scream.

“AHHH-AHHHH!” She just stood there. I let another scream fly, “AHHH-AHHHH!” It wasn’t a dream. I slammed and locked the door. “AHHH-AHHHH!” She just stood there. I let another scream fly, “AHHH-AHHHH!” It wasn’t a dream. I slammed and locked the door.

I looked out the peephole. she just stood there. I thought she would understand screaming. People in Cambodia must scream. She stood there and I was trapped. I couldn’t go out there and pretend like nothing had happened. Those had been loud screams. Then minutes went by. Every thirty seconds she reached up to gently knock. There wasn’t anything to do. I was going to be late for work. Another ten minutes passed. I stepped back to sit on my mattress. I called work and told them I had an emergency errand to do and I would be an hour or so late. I looked out the peephole. she just stood there. I thought she would understand screaming. People in Cambodia must scream. She stood there and I was trapped. I couldn’t go out there and pretend like nothing had happened. Those had been loud screams. Then minutes went by. Every thirty seconds she reached up to gently knock. There wasn’t anything to do. I was going to be late for work. Another ten minutes passed. I stepped back to sit on my mattress. I called work and told them I had an emergency errand to do and I would be an hour or so late.

There was a loud knock. There was a loud knock.

“This is the Madison Police, open the door.” Someone had heard the screaming. It would be hard to explain why a twenty-four year old blonde man was afraid of a ninety pound, unarmed woman. I got up and answered the door. The cop was in full uniform, cap included. “This is the Madison Police, open the door.” Someone had heard the screaming. It would be hard to explain why a twenty-four year old blonde man was afraid of a ninety pound, unarmed woman. I got up and answered the door. The cop was in full uniform, cap included.

“What happened here?” he asked. I gave him the truth but stretched it. “What happened here?” he asked. I gave him the truth but stretched it.

“This lady’s been harassing me,” I said pointing at her.“And?” “This lady’s been harassing me,” I said pointing at her.“And?”

“This morning she just burst into my room and started making these sexual comments. I’ve told her to stop. This had been going on for a week, and like I said, this morning she just burst in.” “This morning she just burst into my room and started making these sexual comments. I’ve told her to stop. This had been going on for a week, and like I said, this morning she just burst in.”

“What was the screaming for?” he asked. “What was the screaming for?” he asked.

“I was telling her to get out.” The cop went over and spoke to her. “I was telling her to get out.” The cop went over and spoke to her.

He’d ask a question and she would say “yes” or “no”. We stood out in the hallway for quite some time. I hoped that my story would hold up. He’d ask a question and she would say “yes” or “no”. We stood out in the hallway for quite some time. I hoped that my story would hold up.

The cop started lecturing her, in English. I’m not sure how much she understood. He was telling her to stay away form me. The cop started lecturing her, in English. I’m not sure how much she understood. He was telling her to stay away form me.

“She’s not going to bother you anymore and you aren’t going to scream at her,” the cop said. “I could take you both in next time.” I nodded and agreed to the deal. We went back to our rooms and the cop left the building. I waited a few more minutes and went to work. “She’s not going to bother you anymore and you aren’t going to scream at her,” the cop said. “I could take you both in next time.” I nodded and agreed to the deal. We went back to our rooms and the cop left the building. I waited a few more minutes and went to work.

I don’t know what she did next, if she cried or if she was angry. I saw her around the building once in a while for a few weeks, and then she was gone. She either died or moved out. I don’t know what she did next, if she cried or if she was angry. I saw her around the building once in a while for a few weeks, and then she was gone. She either died or moved out.

Cul De Sac, by patricia fitzgerald

When I couldn’t sleep, which back in my high school days was often, I used to go for 2:00 a.m. walks down my block. I’d wait on the front steps of my parents’ split-level ranch house until the neighborhood noises gradually ceased. I would imagine them stopping one by one, like harmonizing voices dropping out of a round - TV’s turned off, garage doors grinding shut, water sprinklers not even dripping, the lawns drying in the suburban dark. Then I would start my one-block traveling, barefoot because the asphalt was finally cool enough to allow it. Sometimes I’d swipe a bottle of beer from my father’s stash in the small garage refrigerator. If he noticed the gaps in the well-stocked rows, he never said anything about it to me. When I couldn’t sleep, which back in my high school days was often, I used to go for 2:00 a.m. walks down my block. I’d wait on the front steps of my parents’ split-level ranch house until the neighborhood noises gradually ceased. I would imagine them stopping one by one, like harmonizing voices dropping out of a round - TV’s turned off, garage doors grinding shut, water sprinklers not even dripping, the lawns drying in the suburban dark. Then I would start my one-block traveling, barefoot because the asphalt was finally cool enough to allow it. Sometimes I’d swipe a bottle of beer from my father’s stash in the small garage refrigerator. If he noticed the gaps in the well-stocked rows, he never said anything about it to me.

The cars in the driveway were cold to the touch, their motors only dead pistons and hoses under the hoods. No one had car alarms. I’d have bet that most of the front doors were open, too. It pleased me to think I could’ve just walked right in, looked into their pantries, rubbed the palms of my hands over their vacuumed carpets. These people slept the secure, well-fed sleep of parents, obedient children, men and women with jobs in air-conditioned buildings. Even at night, the wind on my street was warm. It was like the breath of a possessive lover, hovering suspiciously over my shoulder. It kept me walking in a slow, sneaky prowl. The cars in the driveway were cold to the touch, their motors only dead pistons and hoses under the hoods. No one had car alarms. I’d have bet that most of the front doors were open, too. It pleased me to think I could’ve just walked right in, looked into their pantries, rubbed the palms of my hands over their vacuumed carpets. These people slept the secure, well-fed sleep of parents, obedient children, men and women with jobs in air-conditioned buildings. Even at night, the wind on my street was warm. It was like the breath of a possessive lover, hovering suspiciously over my shoulder. It kept me walking in a slow, sneaky prowl.

The neighborhood cats were out. Not quite the same creatures who purred on the arm rests of over-stuffed couches, who preened in front of windows. They hissed and rubbed against each other, their eyes glowing and unfamiliar in the bushes. They would show up on the doorstep in the morning, bleeding from gouges, hungry, very hungry, and tired. I never tried to pet the cats at 2:00 a.m. But I enjoyed their camouflaged and crouching presence. The neighborhood cats were out. Not quite the same creatures who purred on the arm rests of over-stuffed couches, who preened in front of windows. They hissed and rubbed against each other, their eyes glowing and unfamiliar in the bushes. They would show up on the doorstep in the morning, bleeding from gouges, hungry, very hungry, and tired. I never tried to pet the cats at 2:00 a.m. But I enjoyed their camouflaged and crouching presence.

Big Wheels sprawled, turned over and upside down, in front yards. Empty bird baths caught the moon’s light. In the summers, sun-bathers often left their lawn chairs outside, half-full bottles of sun tan lotion, the coconut-smelling contents seeping into the grass. Grass was not green at this time of night. There were no colors, just shades, different densities of shadow. Occasionally there would be a light left on inside a house, in the hallway or an upstairs bedroom or kitchen. I would wonder if these were the signs of others not able to sleep. Men and women maybe working on crossword puzzles, watching their children twitch with dreams, souring the burnt bottoms of sauce pans. I had listened to the next door neighbor talking to my mother once. Reveling that she would wake up at night sometimes and go downstairs to the kitchen and count the silverware. Knives, forks, spoons, just to make sure that nothing was missing. That woman’s home was the one with the tree house in the front. Her kid had fallen out of it one summer and broken his back. The accident had paralyzed him from the waist down, and they had attached ramps to all their doorways. The tree house was still there, like a monument. On my sleepless walks, I would pause and touch the skid marks his wheel chair left on their driveway. Big Wheels sprawled, turned over and upside down, in front yards. Empty bird baths caught the moon’s light. In the summers, sun-bathers often left their lawn chairs outside, half-full bottles of sun tan lotion, the coconut-smelling contents seeping into the grass. Grass was not green at this time of night. There were no colors, just shades, different densities of shadow. Occasionally there would be a light left on inside a house, in the hallway or an upstairs bedroom or kitchen. I would wonder if these were the signs of others not able to sleep. Men and women maybe working on crossword puzzles, watching their children twitch with dreams, souring the burnt bottoms of sauce pans. I had listened to the next door neighbor talking to my mother once. Reveling that she would wake up at night sometimes and go downstairs to the kitchen and count the silverware. Knives, forks, spoons, just to make sure that nothing was missing. That woman’s home was the one with the tree house in the front. Her kid had fallen out of it one summer and broken his back. The accident had paralyzed him from the waist down, and they had attached ramps to all their doorways. The tree house was still there, like a monument. On my sleepless walks, I would pause and touch the skid marks his wheel chair left on their driveway.

Three houses down from us lived a man whose wife had left him. She had cooked me a hot dog once at a barbecue, had asked me if I wanted relish. She had nice teeth, small and glossy like chiclets. They were both young, mid-thirties. I don’t remember how I had heard she was gone, but her leaky black pick-up had suddenly vanished form the driveway, leaving behind an oil stain. The man mowed his lawn every week after his wife’s pick-up had disappeared, his shirt off, his body and face violently red, like he was on big blood clot. He was a nice man, mostly a friendly guy, but wouldn’t say hello or even look at you when he was shoving around that mower. Three houses down from us lived a man whose wife had left him. She had cooked me a hot dog once at a barbecue, had asked me if I wanted relish. She had nice teeth, small and glossy like chiclets. They were both young, mid-thirties. I don’t remember how I had heard she was gone, but her leaky black pick-up had suddenly vanished form the driveway, leaving behind an oil stain. The man mowed his lawn every week after his wife’s pick-up had disappeared, his shirt off, his body and face violently red, like he was on big blood clot. He was a nice man, mostly a friendly guy, but wouldn’t say hello or even look at you when he was shoving around that mower.

My street was a cul de sac, so I never had to worry about cars coming by at that hour. The curb was lined with trees that looked like old men in the dark. No street lamps, but most people left a porch light on. I used to imagine that they kept them on form me, for my midnight wanderings. Moths and junebugs grouped inanely around the glow, struggling and searching for something their instincts told them was there. It was quiet, utterly quiet, except for the occasional bug zapper. Lizards would climb inside the cages, thinking they had found themselves a bug feast. They were electrocuted in long, sizzling bursts that no one heard but me. There was this older boy on the block who knew how to make lizards bite the end of his nose. He’d run after the little kids, screaming in mock horror, with a lizard dangling off the front of his face. I thought it was pretty funny, but then he went away to college and had forgotten to teach someone else the trick. My street was a cul de sac, so I never had to worry about cars coming by at that hour. The curb was lined with trees that looked like old men in the dark. No street lamps, but most people left a porch light on. I used to imagine that they kept them on form me, for my midnight wanderings. Moths and junebugs grouped inanely around the glow, struggling and searching for something their instincts told them was there. It was quiet, utterly quiet, except for the occasional bug zapper. Lizards would climb inside the cages, thinking they had found themselves a bug feast. They were electrocuted in long, sizzling bursts that no one heard but me. There was this older boy on the block who knew how to make lizards bite the end of his nose. He’d run after the little kids, screaming in mock horror, with a lizard dangling off the front of his face. I thought it was pretty funny, but then he went away to college and had forgotten to teach someone else the trick.

My best friend lived down at the end of the cul de sac. He had trouble sleeping, too. I used to climb up the stone pillars holding up his balcony, swing myself over the railing and knock on the window to his bedroom. I’d bring him one of my father’s beers, and we’d dangle our legs off the side of the balcony, watching the sun come up and the kitchen lights in the houses flicker on. We’d talk about moving away, moving either into the city where there was traffic all hours of the night, or into the absolute country where there weren’t even enough people to scare away the mountain lions. Not this in between place, this dead end where lost drivers turned their cars around and headed back out again. Around junior year of high school, my best friend fell in love, and not with me. With a girl who drove a white Volkswagen convertible. Some nights I’d walk by his house and see that car parked in his driveway. His parent were liberal that way; they listened to Joni Mitchell a lot. Eventually, I think I forgot how to climb stone pillars and sneak quietly on balconies. My best friend lived down at the end of the cul de sac. He had trouble sleeping, too. I used to climb up the stone pillars holding up his balcony, swing myself over the railing and knock on the window to his bedroom. I’d bring him one of my father’s beers, and we’d dangle our legs off the side of the balcony, watching the sun come up and the kitchen lights in the houses flicker on. We’d talk about moving away, moving either into the city where there was traffic all hours of the night, or into the absolute country where there weren’t even enough people to scare away the mountain lions. Not this in between place, this dead end where lost drivers turned their cars around and headed back out again. Around junior year of high school, my best friend fell in love, and not with me. With a girl who drove a white Volkswagen convertible. Some nights I’d walk by his house and see that car parked in his driveway. His parent were liberal that way; they listened to Joni Mitchell a lot. Eventually, I think I forgot how to climb stone pillars and sneak quietly on balconies.

There was one empty house, next door to his. The for sale sign had been stuck in the unfertilized dirt since I had moved to the street. The bright, optimistic blue lettering had faded in the brutal summers. I had heard the rumors about that house, about the old couple who lived there. The husband, a doctor or something like that, had blown his brains out one night on their front porch. Some people had suggested Alzheimer’s, but no one really knew why he did it. I imagined the sirens of the ambulance tearing through this 2:00 a.m. suburban silence, the neighbors already awake and frightened by the sound of the shotgun. I imagined sheet-wrinkled faces peering through windows, everyone’s heart beating at the same rapid, terrified pace. There was one empty house, next door to his. The for sale sign had been stuck in the unfertilized dirt since I had moved to the street. The bright, optimistic blue lettering had faded in the brutal summers. I had heard the rumors about that house, about the old couple who lived there. The husband, a doctor or something like that, had blown his brains out one night on their front porch. Some people had suggested Alzheimer’s, but no one really knew why he did it. I imagined the sirens of the ambulance tearing through this 2:00 a.m. suburban silence, the neighbors already awake and frightened by the sound of the shotgun. I imagined sheet-wrinkled faces peering through windows, everyone’s heart beating at the same rapid, terrified pace.

Sometimes I wished I liked cigarettes, so I could leave half-smoked, crushed butts on my neighbors’ lawns. Instead, I’d set my empty beer bottle on someone’s doorstep, like an old-fashioned milkman. Crazy teenagers, they’d think when they walked out to get the morning paper. But it was just me. I wasn’t crazy. Just couldn’t sleep. Sometimes I wished I liked cigarettes, so I could leave half-smoked, crushed butts on my neighbors’ lawns. Instead, I’d set my empty beer bottle on someone’s doorstep, like an old-fashioned milkman. Crazy teenagers, they’d think when they walked out to get the morning paper. But it was just me. I wasn’t crazy. Just couldn’t sleep.

The walk would take me about thirty minutes. Longer if I stretched out in someone’s grass, staring up at the stars for a while. I’d think how it was funny, that someone in another state, maybe California or Kansas or Alaska, was seeing exactly the same stars I was. I liked the smell of freshly mowed grass, the tickle of the blades on backs of my legs. I’d bury my face deep into the stiff points of the lawn, breathing it in deeply, the essence of my neighborhood. The walk would take me about thirty minutes. Longer if I stretched out in someone’s grass, staring up at the stars for a while. I’d think how it was funny, that someone in another state, maybe California or Kansas or Alaska, was seeing exactly the same stars I was. I liked the smell of freshly mowed grass, the tickle of the blades on backs of my legs. I’d bury my face deep into the stiff points of the lawn, breathing it in deeply, the essence of my neighborhood.

Then I’d walk back to my parent’s split level ranch house. It always surprised me how unfamiliar it seemed, even after six years of living there. Like a distant relative’s home I was visiting for an extended period of time. I’d check the numbers on the mailbox just to make sure this was really the place where I lived. Then I’d walk back to my parent’s split level ranch house. It always surprised me how unfamiliar it seemed, even after six years of living there. Like a distant relative’s home I was visiting for an extended period of time. I’d check the numbers on the mailbox just to make sure this was really the place where I lived.

Ours was the house with the barren yard, even though my parents were always trying to grow something. Grape vines, damaged and dry as dirt, hung shamefully from a wooden frame my father had built specially for them. I wanted it to be different at night, with blooms and fragrances and moistness, as if sometime during my walk I had entered a secret portal that only existed when everyone else was asleep, a portal leading to an overgrown world. But the house was always the same, the grapevines withered even in the merciful dark. Ours was the house with the barren yard, even though my parents were always trying to grow something. Grape vines, damaged and dry as dirt, hung shamefully from a wooden frame my father had built specially for them. I wanted it to be different at night, with blooms and fragrances and moistness, as if sometime during my walk I had entered a secret portal that only existed when everyone else was asleep, a portal leading to an overgrown world. But the house was always the same, the grapevines withered even in the merciful dark.

That was many years ago, the cul de sac and my teenage sleeplessness. I live in a city now, a small, crowded city where I walk out of necessity instead of choice. But not at night. I stay inside at night, and keep my doors locked. It’s too dangerous. I’m no longer alone in my insomnia. I still think about moving to the absolute country, live on a farm somewhere, but the mountain lions might come for me in a territorial rage. In a way, I miss the suburbs, the trees that looked like ancient men. The overturned Big Wheels and the rotting nets of basketball hoops. I guess there were dangers there as well. Small fears that seem as heavy as a split-level ranch house to the hearts and minds of my used-to-be neighbors. That was many years ago, the cul de sac and my teenage sleeplessness. I live in a city now, a small, crowded city where I walk out of necessity instead of choice. But not at night. I stay inside at night, and keep my doors locked. It’s too dangerous. I’m no longer alone in my insomnia. I still think about moving to the absolute country, live on a farm somewhere, but the mountain lions might come for me in a territorial rage. In a way, I miss the suburbs, the trees that looked like ancient men. The overturned Big Wheels and the rotting nets of basketball hoops. I guess there were dangers there as well. Small fears that seem as heavy as a split-level ranch house to the hearts and minds of my used-to-be neighbors.

Beer & Wives, by Daveed Gartenstein-Ross

The little man wanted to see, so he tugged my slacks at the ankles. I almost didn’t notice him. I wondered if he lived in constant fear of begin trod upon by somebody’s sneakers. When I did notice him, I couldn’t hear him, so I lifted him up by his little shirt. I wondered where he got a shirt that small. The little man wanted to see, so he tugged my slacks at the ankles. I almost didn’t notice him. I wondered if he lived in constant fear of begin trod upon by somebody’s sneakers. When I did notice him, I couldn’t hear him, so I lifted him up by his little shirt. I wondered where he got a shirt that small.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ he yelled into my ear. ‘Excuse me, sir, I can’t see. Could I please sit on your shoulder?’ I let him sit there for the duration of the film. It felt awkward, like how people usually don’t broach the subject of physical deformity - Excuse me, sir, how did you lose your leg? Hey man, how long have you had that unsightly growth protruding form your forehead? (You know, I once knew a man with five penises. At this point you should My God, how did his pants fit him? Answer: Like a glove.)But you don’t just ask a midget, ‘Gosh, how did you get so short?’ This seemed all the more difficult. He’s asking to sit on my shoulder, which is some acknowledgment of physical abnormality. But do I ask how he got so small? ‘Excuse me, sir,’ he yelled into my ear. ‘Excuse me, sir, I can’t see. Could I please sit on your shoulder?’ I let him sit there for the duration of the film. It felt awkward, like how people usually don’t broach the subject of physical deformity - Excuse me, sir, how did you lose your leg? Hey man, how long have you had that unsightly growth protruding form your forehead? (You know, I once knew a man with five penises. At this point you should My God, how did his pants fit him? Answer: Like a glove.)But you don’t just ask a midget, ‘Gosh, how did you get so short?’ This seemed all the more difficult. He’s asking to sit on my shoulder, which is some acknowledgment of physical abnormality. But do I ask how he got so small?

I didn’t, at any rate. I almost forgot about him as the film ended, when he grabbed onto my earlobe and hauled himself up to scream directly into me ear. The voice still wasn’t much more distinct than a whisper, but I could make out what he was trying to say. Excuse me, sorry to bother you again, but I have to use the restroom. I didn’t, at any rate. I almost forgot about him as the film ended, when he grabbed onto my earlobe and hauled himself up to scream directly into me ear. The voice still wasn’t much more distinct than a whisper, but I could make out what he was trying to say. Excuse me, sorry to bother you again, but I have to use the restroom.