|

Dusty Dog Reviews The whole project is hip, anti-academic, the poetry of reluctant grown-ups, picking noses in church. An enjoyable romp! Though also serious. |

|

Nick DiSpoldo, Small Press Review (on Children, Churches and Daddies, April 1997) Children, Churches and Daddies is eclectic, alive and is as contemporary as tomorrow’s news. |

Volume 199, August 2009

The Unreligious, Non-Family-Oriented Literary and Art Magazine

Internet ISSN 1555-1555

see what’s in this issue...

...You can also click here for the

e-book/PDF file for this issue.

poetry

the passionate stuff

The Fire

Julia O’Donovan

I was getting blemishes on my face

My pores were dirty

Then I realized

I hadn’t showered since the fire

Would have been no use

There was smoke damage everywhere

The shower. I would have mixed soot and water

And made myself worse

We went out of town that week-end

To get away from it all

I couldn’t relax, I kept seeing flames

Shooting in my face

Beyond the Sea

Michael Ceraolo

The lobsters interviewed in the newly-discovered cave colonies

expressed extreme surprise that the humans,

by their flailing and wailing,

were objecting to being boiled alive before being eaten

Sorry, Your Soul Just Died

(Ms.) James Savage

If you saw a child drowning

You’d jump in and save them, wouldn’t you?

Well, apparently not, apparently no one cares

When parents who’ve known every day

That their children were being raped

Throw up their arms and say “Well, what could we do?”

If you saw women being mauled by rabid animals

You’d try to save them, wouldn’t you?

Well, apparently not, apparently no one cares

When a rapist is given three years in prison

After being convicted of one of the most heinous crimes there is

While everyone throws up their arms and says “It happens”

If a plague outbroken was killing people daily

You’d try to stop the spread of the virus, wouldn’t you?

Well apparently not, apparently no one cares

That there are virgin children

And faithful wives dieing of AIDS

And everyone just throws up their arms and says “What do I care, it’s not me”

If you were slowly getting frostbite that would become gangrene

You’d try to save yourself from dieing, wouldn’t you?

Well apparently not, apparently you don’t care

You want to be cold and numb

And blackened to dead inside

Then tell others you’re happy but never believe yourself

My Dead Daughter

Janet Kuypers

I keep getting this image in my head

of a little girl, and she has long straight dark hair

and she is quiet and she comes to me and asks me questions

and I am working, but I turn around to answer her

and she sounds really intelligent

and I treat her that way and I answer her like an adult

and then I wonder if I’m not spending enough time with her

so while I’m answering I turn off my computer

and I turn around to her and I continue to look at her

I make a point to make eye contact when I communicate with her

and I get up so we can walk to the library

as I finish answering her question

and we get to the library and I ask her

is there is anything else she wants to know

because I want to be the one to tell her the truth

and she says no

she says she doesn’t need anything

and underlyingly she makes me feel as if she doesn’t need me

and I think,

I gave birth to that girl, she has to need something from me

and maybe she’s a smart girl

and maybe she’s learned to do things on her own

maybe she does all the things I have had to do in my life

maybe she understands more than I ever did

but these are my memories

these are the memories of something that has never happened

and will it ever?

I always imagined a girl

maybe that’s the maternal side of me,

being a mom and knowing women

but I never knew who the father was

and I never got her name, whenever I would have these memories

maybe she never had one

Order this iTunes track:

in different styles:

from the Chaotic Collection

...Or order the entire 5 CD set from iTunes:

CD:

Listen (2:54)  (mixed 04/23/08)

(mixed 04/23/08)

to this poetry, combined with music

from the HA!Man of South Africa

creating “from Chicago the South Africa”

Listen  to the DMJ Art Connection,

to the DMJ Art Connection,

off the CD the DMJ Art Connection Disc One

Watch this YouTube video

of this poem read live in Chicago 09/12/03 at the “the Cycle of Life” DvA art gallery show

Or watch the FULL video

from the Internet Archive of the whole live the Cycle of Life DvA art gallery 09/12/03 Chicago show

Listen

Listen  to the live track (1:54, 09/12/03) or listen

to the live track (1:54, 09/12/03) or listen  to the studio track (1:32, 10/25/06) from the DvA Art Gallery Chicago 09/12/03 performance The Cycle of Life.

to the studio track (1:32, 10/25/06) from the DvA Art Gallery Chicago 09/12/03 performance The Cycle of Life.

Order this iTunes track:

from the poetry audio CD etc.

etc.

...Or order the entire CD set

from iTunes or Napster

CD:

CD:

CD:

Order this iTunes track

from the poetry audio CD

“Oh.” audio CD

...Or order

the entire CD set from iTunes:

Listen: (2:43)

to this recording from Fusion

Order this iTunes track from the collection poetry music CD

the Final ...Or order the entire CD from iTunes:

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem My Deal Daughter live 6/24/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem My Deal Daughter live 6/24/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (filmed with a Canon fs200)

Heart of the Child, art by Mark Graham

Why I’m Not Submitting

to your Magazine

John C. Erianne

Sure kid, I’m flattered by

the offer and in another life,

I might be persuaded

to stuff something

in an envelope

for you.

But, you see, I’ve

learned the meaning

of futility -- beat my head

against its stoney

silence daily for

40 years.

Literary rags offer

a dubious kind

of fame and

on my worst day

I cannot write

badly enough

or be well-liked

enough for

most of those

places to publish

me.

And although

I am sure you are

good people,

I doubt you offer me

anything I can’t

get standing in

the middle of

traffic shouting

at the sky.

I’ve long accepted

that I will be a

posthumous

man.

When I die they

will assemble

to piss on my grave

or make love at my grave.

Clergymen will

set themselves on fire

and there will be

weeping and cursing

and singing.

Beautiful women

will get wet reading

my poems

drunken rednecks will

run around naked with

4th of July sparklers

dangling from their

assholes.

When all is said and done --

when I am dead

they will all finally be

made to remember.

How Many Doors, art by Edward Michael O’Durr Supranowicz

Poem from the Blue Danube

Lounge & Restaurant:

Fine Dining, Cocktails, and

Every Night Polka Music (Drinking)

Kenneth DiMaggio

“It’s either us

or the drinking”

--but so far

the record

goes to Earl & Phyllis

for threatening

to secede

from a marriage

that may not have

much love or sex

anymore

but would always

have enough alcohol

to pass out together

--for which

they had their own

special corner

--their stupor

never very long

once the bikers

at the bar

pelted them with

bottle caps pretzels

and salt & pepper shakers

--rousing from

Phyllis & Earl

“Sons a bitches!”

“Fuckers!”

“Let’s go kick their asses!”

--Phyllis fist-ready

to slug one or two

of those bad boys

who were young enough

to be her sons

But Earl

pulling her back

more sober in

knowing

if not for their drinking--

--who would there be

to protect him

and who would he have

to save & support

when he no longer

needed protecting

MaiI

John P. Campbell

i love receiving tons of mail

i read every piece of mail i get

the way i see i don’t receive any junk mail

one piece of mail is as important as any other piece of mail

i closely examine every piece of mail that is sent to me

i don’t miss a thing when it comes to my mail

i even read the advertisements and special offers

i never if they will have something i’m looking for

mail is a very important part of my life

without my mail i would have nothing

mail is the only contact i have with the outside world

mail is how i pay my bills and keep in touch with friends

waiting for the mail everyday fills me with excitement

cause i never know what kind of mail i’ll be getting

receiving mail is the highlight of my life

i look forward to the mail each and every passing day

theres nothing more gratifying to me than getting mail

i feel like an important person when i receive tons of mail

i read every letter as if it were to be my last one

i read every word with intense interest

i respond to most of my mail

but only to further my efforts to get more mail

some people say i should see a therapist

i would but only through written correspondence

i don’t see myself as a crazy person

simply because i like to receive lots of mail

i thought about taking a correspondence course on mailology

to expand my knowledge on the mail system

i don’t have a telephone or even a television

all the information i get is strictly through the mail

i and my mail carrier have a special bond

we’ve gotten to know each other very well over the years

i tip my mail carrier every chance i get

and write him thank you notes whenever i can

if it wasn’t for my mail carrier delivering my mail

i would be lost and shut off from the world

if it wasn’t for my mail i would be a wondering soul

lost in the unclaimed pile for eternity

theres nothing more satisfying than sorting through my mail

for it is my only link to civilization

for me receiving mail is what sustains me

except on sundays and holidays

Six Apartments, art by Peter Bates

who also has an art gallery at pixelpost

Argyle

Natalie Williams

Ashen faced;

her soul now weaved into moments of loss and

despair. Coloured by grief-stricken

tears; death is her loom.

The threads of her forgotten self

knitted back; now shabby coat, shag-piled and

broken.

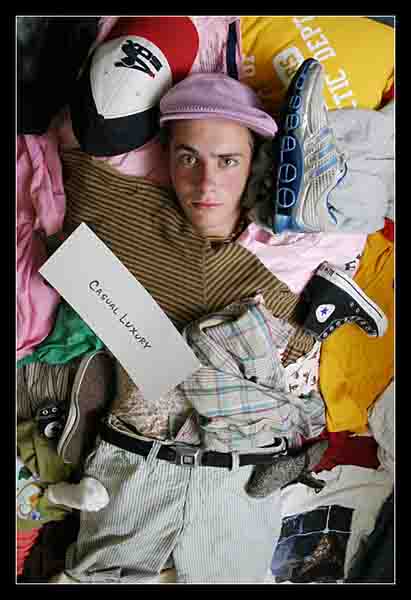

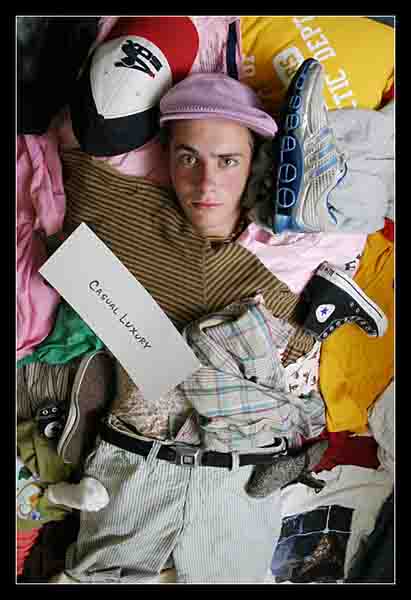

Clothes, art by Nick Brazinsky

If I Breathe

David J. Thompson

November then; the trees had lost

their splendor. We were up the Hudson,

in the woods past Poughkeepsie, talking

poetry at a conference when we heard

that Dylan Thomas was dying. My friend,

John Berryman, said, I’m breathing for Dylan,

if I breathe for him, perhaps he will remain alive.

He and I got to back to the City in the morning,

went straight to Dylan’s room at St. Vincent’s.

A nurse told us his wife was there the day before,

a bottle of rye stashed in her coat. She screamed

she felt like a bride, tried to climb in bed with him,

and tore a crucifix down from the wall. Security came,

took her away, probably to Bellevue.

When I came back with sandwiches and coffee

for lunch, the lights were out and the shades drawn.

I put my arm around John’s shoulders and we stood

bedside, swaying slightly from side to side to the rhythm

of some silent hymn we both were hearing. I could sense

him trying so hard not to cry that I pulled him closer

to me, felt his beard against my cheek, and whispered

to him to remember always to breathe.

Foil Leaves, art by Mike Hovancsek

Evil Floats

(the mind of John)

Janet Kuypers

Evil floats

it is lighter than air

it will always rise to the top

Watch this YouTube video

John Yotko reading live, the 2009 Cana-Dixie Union 05/09/09, Memphis

Watch this YouTube video

(studio session 03/16/09)

American Cathedral

J. Neff Lind

If you dropped

a Wal-Mart superstore

into a dusty

third world village

they would all

gladly spend their souls

on credit cards

and worship

at the altar

built of

row on row

of things they didn’t

realize

that they needed

‘til they saw them

under fluorescent lights.

At Wal-Mart

you can buy

a frozen pizza

a big screen TV

a lawn mower

and a 12 gauge

pump shotgun

with one swipe

of your credit card.

They even have

black powder

which I use

to make

signal flares

when I can’t find

anyone

to lead me to

the Aspirin.

a bit about J. Neff Lind (in his own words)

I have worked as a Parisian busker, a medicinal cannabis cultivator, a bar-tender, a bouncer, a short order cook, a house flipper, a French tutor, and a Hollywood intellectual prostitute.

I’m allergic to ball point and roller ball pens, as well as pencils. I collect fountain pens, but earn minimum wage. My collection grows slowly.

I can dunk a basketball behind my head. I can bench press 350 pounds.

I have never gone to jail or to church. I have gone to six different colleges (and quit five times with a cumulative 3.9 gpa). Sixth time’s the charm!

I sleep every night with my dog Killer. Every morning I wake at 4:00 to bang my head against the walls of the ivory tower. Poetry must be freed! The foundation is slowly cracking. My skull is only getting thicker.

846559187_4365afafcb, art by Paul Baker

They Watched From Their Windows

Mel Waldman

When I was a younger man, a man of dreams and vision,

I read about the poor woman who was raped.

They watched from their windows and did nothing. It’s

true. It really happened. No one called 911. No one

helped her.

In the Times, I read about the heinous act that humans

witnessed. Later, we talked about it in my psychology

classes.

From above, they watched. Yet no one made the call.

What have we learned since that brutal day?

It’s far away in our past, and it’s here-buried in our psyche.

We share the guilt, for it’s our sin of omission.

Beware! Evil’s lurking in the postern of our fractured souls

and out there-in the dark, blemished earth.

Tomorrow, someone will need our help. Shall we find

redemption or by the sin of inaction, condemn ourselves

to Hell?

BIO

Mel Waldman, Ph. D.

Dr. Mel Waldman is a licensed New York State psychologist and a candidate in Psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies (CMPS). He is also a poet, writer, artist, and singer/songwriter. After 9/11, he wrote 4 songs, including “Our Song,” which addresses the tragedy. His stories have appeared in numerous literary reviews and commercial magazines including HAPPY, SWEET ANNIE PRESS, CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES and DOWN IN THE DIRT (SCARS PUBLICATIONS), NEW THOUGHT JOURNAL, THE BROOKLYN LITERARY REVIEW, HARDBOILED, HARDBOILED DETECTIVE, DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE, ESPIONAGE, and THE SAINT. He is a past winner of the literary GRADIVA AWARD in Psychoanalysis and was nominated for a PUSHCART PRIZE in literature. Periodically, he has given poetry and prose readings and has appeared on national T.V. and cable T.V. He is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Private Eye Writers of America, American Mensa, Ltd., and the American Psychological Association. He is currently working on a mystery novel inspired by Freud’s case studies. Who Killed the Heartbreak Kid?, a mystery novel, was published by iUniverse in February 2006. It can be purchased at www.iuniverse.com/bookstore/, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. Recently, some of his poems have appeared online in THE JERUSALEM POST. Dark Soul of the Millennium, a collection of plays and poetry, was published by World Audience, Inc. in January 2007. It can be purchased at www.worldaudience.org, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. A 7-volume short story collection was published by World Audience, Inc. in June 2007 and can also be purchased online at the above-mentioned sites.

Dr. Mel Waldman is a licensed New York State psychologist and a candidate in Psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies (CMPS). He is also a poet, writer, artist, and singer/songwriter. After 9/11, he wrote 4 songs, including “Our Song,” which addresses the tragedy. His stories have appeared in numerous literary reviews and commercial magazines including HAPPY, SWEET ANNIE PRESS, CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES and DOWN IN THE DIRT (SCARS PUBLICATIONS), NEW THOUGHT JOURNAL, THE BROOKLYN LITERARY REVIEW, HARDBOILED, HARDBOILED DETECTIVE, DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE, ESPIONAGE, and THE SAINT. He is a past winner of the literary GRADIVA AWARD in Psychoanalysis and was nominated for a PUSHCART PRIZE in literature. Periodically, he has given poetry and prose readings and has appeared on national T.V. and cable T.V. He is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Private Eye Writers of America, American Mensa, Ltd., and the American Psychological Association. He is currently working on a mystery novel inspired by Freud’s case studies. Who Killed the Heartbreak Kid?, a mystery novel, was published by iUniverse in February 2006. It can be purchased at www.iuniverse.com/bookstore/, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. Recently, some of his poems have appeared online in THE JERUSALEM POST. Dark Soul of the Millennium, a collection of plays and poetry, was published by World Audience, Inc. in January 2007. It can be purchased at www.worldaudience.org, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. A 7-volume short story collection was published by World Audience, Inc. in June 2007 and can also be purchased online at the above-mentioned sites.

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

The Good Olde Days

Arthur Charles Ford

Forced from our distant continent where unspoiled rituals were our daily

prayers, we shared and lived off the land, thus avoiding technocrats feeding

us junk food. The rains came often enough to cultivate our God given earth;

for it was “our supermarket”. Pining for the sight of the morning sun, we

absorbed the freshness of the night carried to us by tribal drum beats. These

beats communicated to us who was healthy, ill, hungry and their location.

We responded!!! We knew not of buying, for “bartering” defined our means

of marketing. Money, memos and contracts were not generated, for we

cherished the trees that God gave us for cosmic ray protection and housing.

Clothing was not abundant, for our bodies were not thought of as a

commodity to be sold, ridiculed or abused. But used to communicate, by way of dance, the pulchritude of God’s most unique machine, and for reproduction-when

He granted it!!

Now here we are today! Encapsulated in a society where avarice, crime,

fame, drugs and nepotism rule. Our surnames are misnomers!!! Our daily

meals no longer blossom in the backyard, but are advertised to us with prices

that depend upon how a Middle East sheik behaves and Wall Street Postings

day to day.The farmer is slowly being replaced by the researching and developing

of synthetic “breakfast”, “lunch” and “dinner. Life itself is being compressed into a pill and a test tube!! Nature is being disobeyed!!!!! Science has yet to categorize racism as a disease, so no cure or treatment is being pursued. The drum beats we now hear are those which lead funeral processions for victims who fell trying to eradicate this disease. This disease (racism) has been modernized and camouflaged. We have succumbed to it, and practice its skullduggeric tactics.

Our concentration on keeping pastures green has been superceded by “the green paper”, which at one time was denied to us. But since then, “some of us” have been allowed to flourish in “some of it”. We lustfully buy elaborate cars, clothing and

waste food, while forgetting or ignoring those of us who are in need of compassion.

But thank God, there are some of us who pensively think about the metamorphic changes we as a people have experienced. Those few, while meeting and greeting at black-tie affairs, devouring caviar, sipping champagne and turning business deals are dying inside to return home, if possible!!!

Yes, return home!!! Way back home!! Back to our culture, honesty and simplicity-back to the good olde days!!!!

Bio-Sketch: Arthur C. Ford, Sr.

Arthur C. Ford, Sr. was born and raised in New Orleans, La. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree from Southern University in New Orleans, where he studied creative writing and was also a member of the Drama Society. He has visited 45 states in the United States and resided for two years in Brussels, Belgium (Europe).

His poetry((lyrics)and prose have been published in newsletter, journals and magazines throughout America and Canada.Recently published by WHIMSIE-E-MAIL OF CANADA, SKYLINE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK, SILVER WING OF CLOVIS, CA.AND KUNTU WORKSHOP OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH. His next book, Reasons for Rhyming (Volume 1), will be released in the near future.

Mr. Ford currently resides in Pittsburgh, Pa. he continues to write, edit and publish poetry and prose.

He has read poetry throughout America, Europe and Canada.

Goodbye, Princess

Christopher Schmitz

Ned briefly looked down from the wheel to use his long, yellowed fingernails to split the pistachio shell. Smiling, he peered over his coke-bottle glasses at his wife; she scowled at him.

“Don’t you look at me like that, pervert.”

“S-sorry,” Ned stuttered, tossing a handful of shells out the window. He couldn’t help it; even though Haroldina had put on more than four hundred pounds these last forty years it just made more of her to love. The mechanics had become more difficult, however, due to Ned’s frail stature as much as Haroldina’s “condition.”

He gulped down a handful of nuts. A couple of them missed his sparsely toothed mouth and lodged into his thick, scraggly beard. Zooming through the Duluth area freeway at a steady forty miles per hour, Ned tilted the bag to offer some pistachios to his beloved.

“Ned! You know I don’t eat salted nuts,” she clutched a half-eaten Double Whopper with both hands. “All that salt is bad for me.” In her revulsion, Haroldina twisted in her seat. “Ow, ouch! Now look what you’ve done, Ned. My fibromyalgia is acting up!”

“Sorry,” Ned repeated. “I didn’t mean ta hurt you.”

“Well ya did!” Haroldina crossed her arms and huffed. “And to think, I was thinking of doing that thing you liked tonight.”

“S-sex?”

“I swear! What is it with you men? It’s never enough that we consummated on our wedding night; you just concentrate on the road. I’m in pain now; there’s no way you’re getting any tonight.”

Ned sighed and looked down to the bay. His daily routine never changed much; truthfully, he felt more like a chauffeur and butler than a husband. Between the weight gain and her fibromyalgia, she couldn’t hardly move without his help anymore. Ned shrugged; at least he had this whole bag of nuts to himself. He cracked a few more shells and ignored the rambling complaints from his wife.

Tossing another nut into his mouth, something caught in his throat. He’d missed a shell and it caught against his uvula. He tried to suppress the gag reflex and cough it out, but couldn’t dislodge it.

Haroldina glared daggers at him. “Are you quite finished?”

Ned smiled at her and nodded. He couldn’t upset his precious. Seconds later, he felt his cheeks flush and his vision got foggier than normal. He shook his head “no.” She wasn’t paying attention any more.

He tried to speak up and tell her he was choking, but couldn’t talk, either. The shell had completely restricted his airway.

Ned picked up his cell phone. Swerving erratically through all three lanes, he scrolled down to an entry titled “Princess” and tried to type a text message to his wife.

Haroldina slapped the phone from his hands; it clattered to the center console. “See why they got this new anti-texting law in this state? You almost killed us, Ned!”

Mustering all his nerve, he glared back at her and sped up an exit ramp. He pulled over near a refinery on the bay side and clambered for his phone. He knew it stunk horribly near the plant but didn’t care; Ned couldn’t smell it because he couldn’t breath. If not the stench, Haroldina would just complain about something else.

He found the entry and furiously hit the keys. Pushing the Send key, Ned got out and walked around to Haroldina’s door and waited for her, his face beginning to purple. He stood there for six seconds while he waited for her phone to chime; she glared at him the entire while.

Taking her time, she methodically dug through her overstuffed handbag and pulled out a pink, jeweled cell phone. She read the message. “‘Give me hemlich?’ Hemlich? I don’t know what kind of crazy stuff you’ve been lookin at on the YouTube, Ned, but I ain’t into that, especially in public!”

His vision crowded with tunnel vision. Wiping a tear from below his thick glasses, Ned typed one more message and clicked send.

The pink phone chimed again. Haroldina read the screen as Ned slumped against the car and slid down to the pavement, his chest fluttering as his lungs panicked.

“‘I lovv you?’ You know what, Ned? You’re a terrible speller!” She slapped her window. “Get up. I’m gonna miss my soaps. You don’t want to see me angry!”

Haroldina peered out her window. “Come on, Ned. Get up. You know I can’t go anywhere without you.”

Ned smiled, exposing a toothless grin with gums blackened from years of chewing tobacco. He tipped over; everything became shaded in tones of surreality.

“Ned? Neddy?”

Haroldina carefully wrapped the remnants of her sandwich in its wrapper and set it down on the dashboard. “C’mon Ned. I ‘lovv’ you too. Now get off the ground.”

His sight fully black now, if he had breath to laugh he would have. Ned suddenly realized that he was just as happy right now as he ever had been in his entire life. He wavered for only a moment, but decided if he had to choose to do it all over again, he wouldn’t change a thing.

In the last flash of life, he imagined himself texting one more message to Haroldina. “Goodbye, Prncess.” And he would spell it wrong on purpose.

The Possibility of Suicide, art by Peter Schwartz

Information on the Artist Peter Schwartz

After years of writing and painting, Peter Schwartz has moved to another medium: photography. In the past his work’s been featured in many prestigious print and online journals including: Existere, Failbetter, Hobart, International Poetry Review, Red Wheelbarrow, Reed, and Willard & Maple. Doing interviews, collaborating with other artists, and pushing the borders of creativity, his mission is to broaden the ways the world sees art. Visit his online gallery at: www.sitrahahra.com.

Boy with the Bones

S. William Hepner

art by David Thompson

Heatship

Frank Fucile

As blue Earth loomed closer below the blinding Sun (shaded only slightly by the ceiling filter) we prepared to convert the Prometheus to reentry configuration, beginning by retracting its thirty-three giant photosails. As we neared the Sun in the past few months, we had increasingly shed our clothing until now we were stripped to heatship casual: anti-radiation briefs to cover our bits and our scrawny tattooed bodies tanned to an almost uniform shade of orange-brown despite daily sprayings of relatively effective anti-burn coat. The heatship had been soaking up as much energy as it could and storing it in its batteries for the long trip back to the edge of the solar system, where it would only have a trickle of photons from the perpetual night sky.

Captain OHandley looked like an Irish pirate with his white-streaked red beard and shaggy floating hair, but his eyes and nose were Asian and his voice Plutonian, widening out in flat aaas to comment distantly on the blackness surrounding us. OHandley loved to sail in open space with the clear polymer bubble above us the only thing between our bronze bodies and the blue-orange photosails floating overhead in empty space. In the pinholed night of our year-long voyages he would proclaim, “And this aaalso has been one of the daaark places of the waaarld,” and laugh stupidly at himself. In addition to being a self-styled literary enthusiast, OHandley fancied himself a direct descendant of the old days of sailing in an open boat at the mercy of the winds and the tides. Now he basked in the distant glow of the planets, stars, and moons that had plagued his distant ancestors, harnessing the power of their photons through the Prometheus’s array of solar cells and photosails and amplifying it in massive hydrogen engines, simultaneously heating the deck and cooling the cargo hold. The term Radiation-Collecting PhotoElectric-Steered Thermal Separation Drive Space Vessel seemed too pretentious, so we called it a heatship.

The Prometheus was a custom job OHandley had built with his family’s fortune. He was a decadent gentleman adventurer who traveled with an impressive library and all-male crew at his disposal. His Plutonian forefathers had been renegade members of the intelligentsia who had escaped to the colonies during the anti-intellectual twitch of the late twenty-first century. Even though they had been successful colonists and businessmen well-versed in technology, they never lost their appetite for knowledge in the form of the old-fashioned paperback. As a result, the older members of OHandley’s crew (particularly myself and my buddy Eskimo Joe) were a self-selected bunch of wannabe intellectuals. The same couldn’t really be said of the younger crewmen.

The Prometheus’s cargo hold was full of Kuiper Belt ice bound for The Big Melted Popsicle (as Joe used to call it). Not that they don’t have freezers down there, but if you’re a rich asshole on a dying planet, why not have your ice flown in from the distant outer reaches of the motherfucking solar system? Especially if inside is the famed Plutonian hash grown under UV lamps in microgravity, baked lovingly in hyperpressurized fission ovens, and pressed into blue-black bricks in the cold space ice. The Plutonians had been pulling off this crazy business model since they settled generations ago, and the Earth’s tangle of crumbling and soaring economic classes managed to keep it profitable.

I of course know this story of the reasons for the Plutonians’ unlikely success because OHandley had drilled it into my head with his stoned ramblings for the past fifteen years I’d worked for him. “Once we sailed to harvest whale oil.” (I remember him thumping a battered copy of Moby Dick on the crystalline roof and drifting down to snag a foothold on the deck.) “Then came coal power. Then we hauled crude.” (He opened his arms to the blank sky and let the book drift away from him.) “Now we have a purely heat-based economy.”

After pulling in the sails, we brought up our heat shield, shutting out the swirl of sea and cloud below us and encapsulating the ship’s deck. The artificial light cells came up, and we strapped ourselves into our bridge seats, calculating speed and trajectory. After the bumpy mess of passing through the atmosphere we activated breaking thrusters, deployed chutes, and splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico. The shields came down and the bridge opened up onto blue sky and green sea. A couple of the greenhorns looked a bit weepy, but the shift to blue after almost two years of black was dramatic even for the old salts. Though certainly nothing in my life ever compared to that first moment. For a man to grow up without ever seeing the Sun as anything but a distant star, and for his home, his real original ancestral home, to be an invisible speck snuffed out.

We know after this shore leave we’ll be hauling passengers and products up to the colonies. And it’ll be a serious, fully-clothed, respectable transport of businesspersons, their families, and their consumer goods instead of sexed-up hashed-out pirate anarchy. Joe used to say the civvies we transported were rats leaving a sinking ship. That’s probably what his grandparents told him about abandoning their ancestral oil-field ice sheet for Europa.

As we unbelted, the misty reveries of the greenhorns were literally crushed by a gravitational force greater than any they had felt before (making them realize how useless those half-assed lifting sessions in the inertial gym were). I even felt sluggish under Earth weight then, and I was in my peak condition. Half the crew wanted to lay down on deck, and OHandley wobbled out in a goddam tricorn hat with a cutlass strapped on his waist, lit a corncob pipe, and shouted, “Raise the sails to caaatch the wind or we’ll never make New Aaarlens.”

The greenhorns moaned, some of them maybe expecting OHandley would actually produce a set of masts and canvass sails and force them to climb through the rigging in their weakened state. But they were still in their space minds. Us older crew knew the Captain was on our side, because now all of a sudden this was Earth, and we were spacers, and systemic pariahs at that. As the bubble came down wind breezed across the deck. A breeze with a smell, the first in two years. And if you’ve been on land before you know what that salt smell means. The bubble is off and you stick with your crew and your captain. Because down there you’re weak. You can feel it in your body and see it in people’s faces.

I gave the greenhorns this sermon in my capacity as first mate while the more experienced of us punched up the command sequences for raising a photosail in full Earth gravity. We couldn’t afford to waste energy by running the thrusters on battery power.

After plotting our course, the older mates began drifting below decks to change into their land threads. Even if we couldn’t be as strong as we needed to for the natural world we could at least be covered up. Some crewmen went with nondescript outfits while others went with retro-wear. Though they sometimes won’t admit it, nostalgia for old Earth can be even stronger among space truckers than civvies. I changed into a grey three-piece suit I had picked up on Mars the last trip (but no shoes or tie, for a less restricted feel). Eventually the greenies caught on and put on street clothes or even space threads if they had no other option. I’ve seen kids get beat up on the docks for coming off the ship in nothing but their shorts.

The dockworkers who unloaded our cargo were always burly men in stained clothing who glared at us suspiciously, resented us for our weakness, despised our way of life. It was rare to get off the dock without somebody at least being called a faggot. As we approached port the veterans fixed themselves into a cold posture and attitude. I stole my last glance at Joe in his jeans and leather jacket. He had been ignoring me since we had put the heat shield up. It seemed to happen farther from port every time. I thought maybe we wouldn’t bunk together on the haul back, but it would be a long trip. I watched him grease his hair like he always did in heavy gravity.

We coasted into port at night under battery power to a shadowy crowd of figures pacing on the dock of the city we called New Orleans. Actually it was somewhere in the area that used to be Arkansas, but it’s too depressing to call it New New Orleans. Everybody always expected these dockhands to be gang thugs, but only the oldest salts who knew the secrets of the Prometheus’s amplification engines realized how deep OHandley was in with the syndicates.

Despite the heatship’s exceedingly frugal use of photoelectric and solar energy, its amplification and battery systems required an embarrassing amount of hydrogen to keep running. So Interplanetary Hydrogen secretly sponsored the Prometheus and most other heatships as a distraction from their ongoing rape of Earth’s atmosphere. In return OHandley traded his Plutonian hash to the Delta Mob (which had a controlling interest in Interplanetary Hydrogen) and got dockworkers who didn’t ask questions.

Very few crewmen were actually aware of this system, and in fact a lot of greenhorns saw working on a heatship as some kind of utopian lifestyle outside the pervasive corruption of terran politics.

And maybe this was why the dockmen hated us so openly. We came off our ship wiggling bare toes on the wet wooden planks of the pier, and it must’ve looked like we were convinced not only that Earth was a wonderful place to be but also that we were actually making it better. And the grim-faced workers sneered at our scrawny bodies in the halogen light and murmured insults as we staggered past on unsteady legs. They winked and laughed and whistled at us. Some would flash the guns in their waistbands as a way of telling us what kind of place this was in case we had any doubts.

But there was one man that night whose blank stare straight into me carried something entirely separate from disdain. He was dressed in a polo shirt and khakis, very unlike a dockworker. Cold eyes and face shaded by black hair. A body less robust than the other hands, casually leaning against the lamppost instead of standing with the men near the edge of the dock.

At first I thought he was a new recruit who hadn’t yet developed a disdain for spacers, but when he caught up to OHandley and me later that night in the bar, he and the Captain looked at each other with the kind of vague familiarity that signaled something was afoot.

The man tapped his fingers on the dark countertop and smirked at the Captain, who ordered him a beer. His sweaty hair stuck out in all directions.

I turned my blurry eyes away from him to Joe in the corner, sipping his whiskey and staring at his shoe.

“Who’s this scrawny weirdo you’re with?”

I looked up to see the dockworker chuckling at me. It wasn’t quite an insult, so I didn’t say anything, though I did find it odd for him to call me weird when I was sitting next to a grown man in what amounted to a pirate costume.

“Sammy,” OHandley said, gesturing to me with one hand as he stroked his beard with the other, “meet Tyler, our man inside.”

I squeezed hard as I could on the handshake and didn’t look him in the eye.

“You boys better be careful around here.”

Boys? Careful of what?

“Gonna be some big changes.” Tyler swigged his beer and tilted his head towards me.

“Go ahead,” OHandley said, then murmured something into his hand about trade secrets.

Tyler and OHandley guffawed for a second.

Then Tyler leaned in. “Hydrogen market’s goin bust.”

He said it so quickly I wasn’t sure he meant it. Especially when Interplanetary claimed the economy would be stable for at least another century. But I’ve already established what crooked fuckers Interplanetary Hydrogen were.

“Overhead’s skyrocketing. They’re running out of materials. Plants are either shutting down or being forced out by the locals, and they’re running out of places to dump the carbon. We’ve got about a month, maybe a month and a half before hyperinflation hits.”

It had happened before after all, with gas, with coal, with ethanol. It was only a matter of time.

OHandley looked into his foamy mug.

I clenched my toes on the wet tile floor.

Tyler leaned in closer, spoke faster, whispering. “You can’t fuck around with this long-haul space captain shit anymore. You gotta break with the Delta Mob and get on board with my plan.”

OHandley spat. “The faaack can you do fer me?”

“Even if you sail back out before the crash you won’t be able to make it back without a refuel. And out there you’ll be up shit creek with those useless photosails.”

OHandley shook his head and slammed his empty glass on the table. “Some faaackin beer daaammit!”

“The only way you can stay afloat is to drop that rig of yours into a Mercury orbit and convert it into a sunmill. And I’ve got the plans to do it. We’ll make a killing selling the energy to Interplanetary.”

It was cruel to tell such an old and passionate man he could never go home, but Tyler was right. The business model was completely fucked without cheap hydrogen.

The Captain finally had his heat economy.

Sensing either an argument or very secret dealmaking coming on, I slid off my stool and padded over to Joe in the corner. He was still alone, finishing that glass of whiskey, and scratching something into the table with his butterfly knife.

“Having fun?” I said.

“Fuck off,” he muttered.

I sat down across from him. His hair was brushed over to the side apparently from falling asleep somewhere, making him look like a drunken Inuit Fonzie.

“Buy me a beer,” he said after a long silence.

When I came back with the beers he had reanimated enough to be flipping through a pocket book of poems.

“Oh come on you’ll have time to read on the way back. Now’s the time to party.”

“I’ve been drinkin since we got in.”

“Fuck you put that book away and talk to me.”

He slapped the book on the table. “Who you talkin to over there?”

“Don’t get jealous. That guy was talking to the Captain.”

“Guy’s a mobster.”

“Wrong again.”

Joe shook his head at me.

“Just because a guy hasn’t had the luxury of spending the past fifteen years with his nose in a book not even having to bother to stand up doesn’t make him a thug automatically.”

“I’m not a fuckin idiot.”

We sat and fumed at each other. I wondered if it would be possible to go home with Tyler.

Joe snorted. “Fuckin Delta assholes.”

I wanted something to storm off on, but instead I chose a more thoughtful exit: “You know it isn’t going to last,” I said. “Men of leisure like ourselves, sailing the system stoned, living off the surfeit of others, reading” (I grabbed the book from under his hand) “Ginsberg or whatever.” And walked on cold tile back to the bar.

OHandley and I stayed for the next week in Tyler’s dusty brown apartment. It turned out he had been a solar power engineer before the smog got so thick that terrestrial units became unfeasible. We went over the modifications that would have to be made to the Prometheus and agreed to bring Tyler on as a partner. He seemed level-headed enough, even though he showed outright disdain for our intellectual and literary tendencies.

There was, however, one topic on which everyone, intellectual or otherwise, had an opinion.

“I’m sure we’ll always be able to come up with new energy sources,” Tyler said nonchalantly.

“Always is a long time,” I said.

I never ended up getting in bed with him. Every time I felt I was getting close he would look at me with those cold eyes and I could feel him laughing behind the mask of his face.

The crash hit a lot faster than we thought it would. In a week and a half the space elevator hiked up tow fees again and the dockworkers threatened to strike if their pay were cut. Suddenly we were in a position where the hash had to sell like gangbusters for us to even make it back out to orbit. But by then the recession had started, and only the richest of assholes were willing to shell out the money for Plutonian Ice Hash. Consequentially we would be forced to sell the bulk of it at a huge loss and install the conversion components for the Prometheus ourselves. But it ended up taking longer than a month to move the hash, and the dockworkers were getting agitated. Tow fees went up again, and soon whole commodity chains started to fold.

With coal and gas plants shutting down everywhere, the overburdened nuclear infrastructure couldn’t keep up with demand. Any kind of energy was suddenly ridiculously expensive. Inter- and intra-planetary commerce fell to pieces. Cities started shutting off power at night. Civil unrest was imminent. The dockworkers threatened us daily. Just when everybody wanted to get off the dying puddle it was most expensive to leave. All the high rollers (including the executives of Interplanetary Hydrogen, who knew they were going under in time to sell their shares) evacuated to the colonies, and we were marooned with only a useless spaceship and a hold full of melting hash.

OHandley withdrew his family’s savings only to find it inadequate compared to the vast sum of money required to fund the expedition. Once hyperinflation set in, we realized there would be no way to get off the planet without a massive loan, and it just so happened that Tyler knew some people who could help us. Never mind they were sketchy people; never mind they were dangerous people. All we had to do was finish those modifications to the Prometheus, tow out to space, drop into orbit for a few years, and we’d come back with more than enough battery power to pay off the loan and ship back out for the next cycle.

Banks were collapsing all around us, and the only people who had the kind of money we needed were the upper echelons of the Delta Mob, so while Tyler had originally come to us claiming we’d be free of them, he ended up taking us right back when we had nowhere else to go.

We took Tyler’s skimmer down the floodplain and through a coastal marsh that probably used to be great farmland to a watery villa. It must have been built before the last melt because the water came up over the front porch. Most of the walls on the first floor had been knocked down (presumably because they had rotted to uselessness), leaving a forest of improvised support columns holding up the second level of the building. Two men in olive drab uniforms meant to imitate mid-twentieth-century Army fatigues stood on the wet porch, long black imitation M-16s pointing into the air. One tilted his head and waved us forward.

We beached the skimmer on the submerged front steps and stepped onto the slimy wooden porch. The water came to my ankles, soaking the cuffs of my dirty grey suit pants. The guards stared at my feet through the murk.

I laughed. “And you guys are getting pond scum all over those nice boots.” I was excessively stoned after deciding there was no way we could unload the rest of our hash.

Tyler smiled and shoved me quickly into the building. Not that there really was anything to go into. More like being under a building.

When the sharks came clunking down the stairs from the upper floor, I had to stop myself from cracking up again. The two of them were dressed in full Napoleonic gear: long blue double-breasted jackets, knee-high leather boots, giant plumed hats, and yellow fringed epaulets. Nostalgia garb is pretty common on Earth, but these were mobsters. It was difficult to take anyone seriously when they were dressed like that on a planet like this. I wondered whether they had planned their style together to impress us with their atavisim or if they dressed like this all the time.

The one on the left spoke in a gravelly voice. “You pansies would be trapped in gravity forever if it weren’t for us.”

“Your corporation’s going baaankrupt.”

The one on the right laughed at him. “You don’t think we have a whole fleet of ships already sailing to the Sun?”

“Obviously not or you wouldn’t be helping us.”

“That’s what you think we’re doing?” The right one smirked.

The leftward Napoleon splashed down off the stairs and paced in front of me kicking waves of muck onto my pants. I decided he was the commanding officer because his motions were those of a leader. As his left hand massaged the pommel of his sabre with lascivious intensity, his right stuffed itself in between the buttons of his jacket. All he needed was something stuffed down his pants to complete the look.

I couldn’t help but chuckle under my breath a little.

The man spun throwing a wave off from his ankles. “What makes you think we didn’t just bring you here to kill you?”

The silence was finally broken by the man’s laughter.

On that signal, a young man, maybe only forteen, slinked down the staircase in some retro-avant-garde chainmail getup with a briefcase handcuffed to his arm.

The lesser Napoleon unbuttoned his jacket and removed a small stack of papers and a pen, stepped awkwardly through the water, and handed them to OHandley, who flipped through the pages, signed them, and handed them back. Then the kid splashed forward and placed the briefcase in the Captain’s hands. The mobster with the sword tossed a single key onto the briefcase. OHandley unlocked the handcuff from the briefcase, and the two generals walked slowly back upstairs with the boy.

When we opened the briefcase, it was filled with pure silver bars, something that was actually gaining value.

We would be able to make it to Mercury and still have enough left over to pay the dockworkers extra for their wasted time so we wouldn’t be attacked when we came back down.

After a year of chasing that planet around the Sun our crew was ready for the trip back to Earth. I had attempted to read Marx’s Capital over the trip but found it filled with hilariously confusing equations attempting to ascribe actual value to things. We knew nothing had any value except what value people thought it did. Numbers are arbitrary.

I asked Joe about it. I remember he used to mention Marx sometimes. He had been reading an absurd amount this time around, even for him. Shirking his duties, hiding in the engine rooms sometimes, his nose in books even I hadn’t ever heard of and probably couldn’t understand. He had been ignoring me since we’d taken Tyler on board, presumably out of jealousy. Now he was tied down in his bunk flipping through a black book with the word Adorno on it.

I pulled myself to him on the handrail and flicked the huge tome in his direction. “Fuck does any of this shit mean.”

He glanced at the cover and smiled. “Nineteenth century obsession with quantifiability. Like a lot of theory, it’s just a fancy way of saying something everybody already knows.”

“Which is...”

“We don’t get paid what our work is worth.”

Silence a moment. Then I pointed to his book and said, “I’ve never seen that one in the library.”

And he erupted. “So you’re gonna bust me for smuggling extra books on ship?”

Technically it was my duty to. Before we launched, the order had come down not to bring anything extra on board that would add to inertial mass. Tyler had wanted to dump the Captain’s whole library to cut down the tow fee, but that proposal was rejected by various hyperliterate crewmen as something that would make the trip unbearable.

I pulled myself onto his bunk. “Your secret’s safe with me, baby,” I whispered.

His face flashed contempt, and he shoved me off.

I spun and pushed off the opposite wall with my foot.

“Leave me alone.”

“Fuck’s your problem?”

He shoved his book angrily under a strap. “I told you we shouldn’t have brought that thug on board.”

“He’s not a thug, he’s an engineer.”

Joe rolled his big eyes again.

For some reason he hated me, and it hurt more than I wanted to admit.

But at that moment a call came over the intercom for a full crew meeting. We assembled on deck, taking care not to face the Sun, which was blindingly close even with full ceiling filters up.

OHandley (in radiation briefs and cutlass, feet clipped to the deck) and Tyler (stubbornly in full land threads, floating) at the front of the bridge shouting to each other in whispers the way married couples do when they don’t want their children to hear. The Captain threw his hand out to the side in what looked like anger. Tyler pushed over to our floating crowd.

“We’ve caaallected enough battery power to make a good profit, aaand I’m suggesting we return now since the paaawer’s needed so much.”

At which point Tyler very rudely pushed off my shoulder to propel himself to the front of the group. I recovered against the ceiling.

Tyler pulled a sheaf of paper from the inside of his (quite inappropriate) jacket. “Unfortunately part of the contract with our lenders promises to maximize profits, meaning we need to orbit another year before...”

He was drowned out by a chorus of moans from the crewmen. “Let’s vote,” someone shouted. Voting on such matters wasn’t uncommon in those days.

Tyler let out an annoying scoff. “It’s a contract. You’ve already signed on. You don’t get to vote on it now.”

“We’ll get enough caaash to pay off the loan aaand have enough energy left to make it to Pluto,” said OHandley. “I say we go home.”

Tyler shook his head and waved his hands in frustration. “You people don’t understand. This isn’t some game where you get to float around the solar system for fun. You’re supposed to be turning a profit. You’re supposed to be businessmen. You...” (and he didn’t have the courage to say it) “...are so caught up in your books and your drugs and your...” (and he didn’t say it again) “...stupid, homoerotic” (he hedged) “fantasy world that you have no idea how to do anything right.”

That’s when Joe grabbed Tyler by the neck and we had to pull the two of them apart.

OHandley stood scowling up at us in the glare of close sunlight, contract papers floating by. “Don’t ever question the way I run my ship, you goose-stepping dirtcrawler. My aaancestors left Earth to get away from aaasshole beancounters like you.”

Tyler said, “Who do you think you’re working for?”

It took us all a few seconds to figure out what happened next. Tyler moved suddenly and there was a loud pop as the Captain fell. But that didn’t make sense in freefall orbit. OHandley had been pushed onto the deck as Tyler flew back into the ceiling. A bullet. From a gun.

Never mind that firearms are completely prohibited on ship. Never mind that firing one in space is completely insane and threatens the whole crew. Thankfully Tyler had been above OHandley so the bullet only went through the deck and not the ceiling enclosure.

But OHandley was dead. We would have killed Tyler right away, but we were frozen in disbelief. Then he spun upside-down and turned the gun on us. We were terrified his next shot would decompress the whole ship.

Tyler kicked off the ceiling bubble and propelled himself to OHandley’s body, where he pulled the Captain’s sabre from the dead man’s belt. “I’m taking command of this vessel in the name of the Delta Trust as stipulated in the contract.” He waved vaguely at the cloud of papers with the sword. “Captain OHandley, having violated the terms of his contract, has been executed as a mutineer. You’ll do better without him anyway. Who’s ready to make some serious cash?”

About half the crew grunted tentative acceptance. They had no loyalty to OHandley. I had overestimated the man’s charisma.

“It’s time you sailors ran this ship like a business and not some queer intellectual adventure.”

Some greenhorns nodded in agreement.

“It’s time to stop floating around like idiots just getting by when you can make a killing off that thing.” Tyler pointed with his gun as he squinted into the blinding Sun.

More nods from the less-experienced crewmembers.

I had never thought there would be a mutiny on the Prometheus, and certainly not a successful one. I was sure Tyler would be dead in a few days and we would be on our way back to Earth.

But instead the crew fell in line behind him. In another week he had us dressing in full space uniforms. Our shift hours were increased with all sorts of meaningless tasks meant to keep us efficient and disciplined. For the first time ever the crew was doing things like cleaning and standing watch. Twice as many crewmen as were necessary would be posted to sail control at any particular time. We were instructed to maintain the solar arrays in the most absolutely efficient positions possible and not to trust the ship’s automatic readjustment systems (which could be off as much as a degree at times).

Eventually smoking was banned on ship. It was deemed counterproductive. People claimed this wasn’t a big deal because they could still find ways to do it secretly. Then came the order to jettison the library. Joe and I took it hard, but only a few other crewmen objected. The atmosphere was one of such fearful seriousness that nobody even spoke as we tossed OHandley’s books into the ejection chamber.

Perhaps knowing we cared the most, the others left Joe and me to finish the job. Joe pushed into the chamber and unzipped his leather jacket, which he had been wearing over his uniform jumpsuit. He motioned for me to get in with him.

Hesitant, but feeling he was the only person I could still trust, I let myself float into the chamber. Joe was already halfway out of his jumpsuit.

He closed the door behind me. The feeling of being in an ejection chamber is a lot like leaning over the edge of a tall building in gravity. As terrifying as it is exhilarating. Joe kicked his jumpsuit off and it drifted to the other end of the chamber.

He fished in his jacket pocket, then nodded and handed me his hashpipe. “Hit this and get out of that gear.”

I took a deep drag from the pipe as Joe stared at the leather jacket in his arms, then passed back to him and started on my zippers.

We were down to heatship casual again, puffing Pluto hash like the good old days. Then Joe grabbed his radiation briefs and, in one quick motion, whipped them down his legs and off his body, exposing the bouncing penis and testicles I hadn’t seen in a year thanks to our tendentious sex embargo.

I let out a cloud of smoke and sneered, squinting into the yellow-orange ball of hydrogen through the tiny window at the far end of the chamber. “You know that’s gonna fuck with your junk.”

Joe just shook his head.

When we finished smoking we floated silently, rebreathing the green-brown carbon dioxide cloud around us.

Joe stared out the window a moment then turned back to me. “You ever wonder why we’ve never come into contact with any aliens?”

“You mean we this ship or we us humans?”

“We anybody.”

“They’ve found lots of alien microbes. All over the system. Mars, Venus, Europa, Callisto, Titan.”

Joe sighed. “I mean intelligent life. Spacemen in flying saucers. That kind of thing.”

I shrugged. “Maybe interstellar travel isn’t workable.”

He raised his eyebrows and a finger, very pedantic. “Ahh, but why?”

I didn’t see what he was getting at.

“I have this theory,” Joe said, “that there are two kinds of species in the universe. Either they’re like us or they aren’t.”

“Well...yeah...but what do you mean by that? That isn’t terribly specific.”

“Either they’re the type of species that has a compulsion to grow beyond their means, or they’re not.”

I stared at him blankly.

“If they keep their numbers and technology under control, we would have no way of detecting them. And if they have a technology fetish like us, they inevitably...” He rubbed his forehead.

There was nothing I could say.

Joe shook his head. “And we’re all marching to self-destruction.”

I wanted to say something about the new power theories I’d been reading about. Researchers were going crazy trying to find new fuel sources, and they were actually making good progress. But what Joe had said made so much sense I felt any attempt to cheer him up would be disingenuous.

“Take this,” he said, pushing the leather jacket into my arms. “Let me stay with the books.”

“What?”

He slid the door open. “Get out of the chamber, shut the door, and hit the button.”

“I can’t do that, Joe.”

“Will you please just listen to me this once?” He looked into my eyes, something like exhaustion on his face.

I touched his bare shoulder before slowly pulling myself back into the ship. I wanted him to suggest mutiny instead. I hoped he would want to take back the ship. Maybe we would die, but at least we would die fighting.

He shut the door.

I watched him through the window and waited for him to change his mind. I put his jacket on to waste time. I waited as long as I could. But I could see in his eyes he had given up.

I heard hands pulling their way towards us down the tunnel.

Joe shouted silently to me, lips flapping wide, and I could see what he was saying: “Hit it fucker.”

The handsteps came closer. I put one hand over my eyes and slammed the jettison button with my other fist.

Eyes closed, I jammed my shaking hands into the jacket’s pockets and found something heavy, cold, metal. When I finally turned around and opened my eyes, Tyler was hanging in front of me.

He looked my half-naked body up and down, squinting his whole face. “What happened to that bookworm butt-buddy of yours?”

Without thinking, I flipped out Joe’s butterfly knife and buried it in Tyler’s throat. Blood plumed out from the stab wound like a sail.

Deadfall

Antonin Dvorak

There’s something out there, I thought, staring through the cracked and dusty windshield of my Dodge Ram, and I need to know what it is.

This was the late 1980s, a time when the nation looked to the sky only to watch the Challenger felled by an O-ring. Bush held office then, I think, and we lived in Canard, California. It’s a place we haven’t visited in years.

The sun was already falling when I set out. It pushed its rays through the mountains and trees just enough to streak the road with a patchy, dusty light. My pickup bucketed down this dirt road on weak shocks, though I’m happy to say that the O-rings were in frisky-fine order, thank you very much. The woods bore down on me from the left, a dense forest that wasn’t completely pine yet. Behind the trees, a sharp-faced mountain jutted up into the sky.

I need to know what it is. My hands clenched the wheel, knuckles gleaming white.

I’ll never forget the way the forest looked that day. It was as if it knew that it was going to let its secret out. When I looked hard enough, I could make out sneering lips and squinty eyes born of twigs and leaves. Those visions frowned and glowered as the winds played through them.

Samantha, my wife, hated what I was doing. She thought that I should have been tending to my daughter and not this tracking nonsense.

“You’ve got stupidity in spades,” she always said, only half-joking.

I pulled the Ram to the side of the road, where the long grass tickled the undercarriage. This wasn’t one of the new Rams, of course. Dodge reinvented the Ram long after this one was on its way out. Mine was boxy and rugged, not sleek like the new ones.

For a moment I just sat there smelling the oily cabin — no rush, as I hadn’t actually heard the howling yet. It was Teddy who had heard her, and I had gone out straight after work.

Climbing out of the truck, my back cracked and I winced a little. If I got lost out there, or if she was to get me, I wanted people to know who and where I was. Just leaving my driver’s license on the dashboard would do the trick. So I fumbled through my pocket, pulled out the license, and a few dollars fluttered to the ground like dying butterflies. I don’t carry a wallet. When people carry wallets, all their spare change ends up there, and they start thinking that they have more change than they can spare. I raked up my money and slipped it into my pocket.

My license caught my eye that day. I don’t know why that was. Maybe it was the way the woods seemed alive. Maybe I was more scared than usual. There I was. The picture had been taken almost four years earlier, and I hadn’t even cared so much as to flatten the cowlick that sat on the back of my head. I looked like Opie on a bad hair day. My name was printed beside the picture and looked too grand to be next to it: Frank Shepherd.

I stared at that snapshot for a minute before deciding that when I got back, we’d all have to go out and get some good pictures taken of us. They had just opened a new photo place in town. Why let it go to waste?

The driver’s license ended up on the dashboard, and I pulled my shotgun — for protection, only protection — from the pickup bed.

I turned away from the truck, slowly, like I was in one of those B movies where there’s some Swamp Thing, Vampire or, yes, Bigfoot. I felt like an actor; this scene couldn’t have been real. The wind eddied at the edge of the forest, making those faces and making the grass ripple like water. It eddied under the truck, the grasses clipping against the underbelly and making a sound like distant applause.

All that wild thought left me once I was in the forest. All thought, really, fled from me. I stepped through the forest skirting and into the shadows. Inside, there was almost no wind. Just squirrels and chipmunks rummaging through the underbrush.

I buttoned up my flannel against the late autumn air and soon I was climbing at an odd angle. It was cool enough down in the valley, but as I went up into the Klamath Mountains, the air went from cool to cold.

I had done this many times before, this tracking, always done it alone and always done it hoping more that I wouldn’t find anything than that I would. For the first hour, with my ears straining to hear her, I walked with just one word in my head: bucolic. My mom called me that when I moved from San Diego to Canard. For a long time I was actually scared to look it up in the dictionary, but when I did, it wasn’t so bad. In her eyes, I was just living the rural life.

Higher and higher I went, the shotgun bouncing against my back. The first hunger pangs picked at my stomach, and I ignored them.

I looked down at my watch: 5:30 pm. An hour gone.

“Where the hell is she?” I whispered. “Teddy said that she was out here. Said he heard her howling, loud and clear.”

And then my eyes fell on what looked like a footprint. I crouched down to the pine needle-blanketed ground and studied the imprint. It was deep, maybe two inches. It was long, too, at least twice as long as my feet. I shifted uneasily, my thick clothes concealing the goosebumps that had sprouted all across my skin.

Damn, I thought.

Huge, I thought.

I didn’t think, Turn back you idiot.

I ran my hand over the cold print. Whatever it was, it had to have been heavy to crush the cold earth down like that. The idea that it might have come from something else never crossed my mind: some rock’s old resting place, some rotted-out root system, some natural phenomenon — no, this was her. I was sure of it. It was her, or it was something.

After a while, one of those feet caught on a knot of tree roots, and I fell forward onto the stiff dirt. I picked myself up and looked down at my watch: 6:28.

By now the hunger pangs weren’t coming and going; they were just there. It was like some tiny rodents were scuttling around in my gut, clawing and spitting angrily, waiting to be fed. I ignored the pain. More important things needed tending.

I walked on. I walked, and I eventually came upon a clearing in the woods. There was no field of grass — this was high in the mountain, remember. All that lived here were scruffy bushes and a chipmunk that hightailed it out of there when I came. Funny that I had never been to the spot before, never noticed it before.

The view from that clearing sticks with me. I can see it like a photograph in my mind, like one of those new photographs, those panoramas or whatever they’re called. I could see for miles out over the green canopies of tree. The Klamath Mountains rolled up and down, into and out of valleys, over and under the milky white fog that had gathered in the dales. The clouds were thick and gray above me. Wherever the sun was now, it was no longer casting its patchy, dusty light here. It wasn’t dark by any stretch of the imagination, not yet, but it wasn’t light either.

I stood there for probably ten minutes, just relaxing, the howling completely out of my mind. The air was so rich. Cold, yes, but rich. It was intoxicating. And in the end, I had to drag myself from the clearing. I still needed to know what was out there.

I pushed on for another ungodly length of time. The cold only got colder. My need only grew stronger. When the next stop came — I stood between a fallen pine, very near to Deadfall Lake — I glanced down at my watch again, 7:48. Only this time I had to look through a shuddery puff of my own breath to see the time.

The hunger pangs would no longer go ignored. My fingers were tight with cold as I unwrapped my sandwich, but I would find her. If she was anything worth finding, I would find her tonight. And I sat down in-between patches of snow like icy toadstools.

The noise started soft and deep, almost like a rhino’s whistle might sound. It grew in intensity until it was echoing in the trees. I could feel the sound against my body; the animal couldn’t have been more than half a mile away.

The animal — I haven’t even told you what I was looking for, have I? No? Well, you’ve probably figured it out by now; this part of the world is Bigfoot country. And Canard, California, seems to be Bigfoot country’s capital. It’s a small tourist town that sits on the Rouge River. Mr. and Mrs. Riley own the Bigfoot Bed and Breakfast. There’s Bob Hastings who owns the Bigfoot Bar and Grill. Teddy Rumsey operates Howl Lodge, a resort very near to where you can always seem to hear the animal screaming. Howl Lodge is where I worked, as a front desk manager. The names are corny, I know. But if there’s a buck to be made, people will do corny.

Some towns are built on legends and myths. That’s all good and well. Some towns make their lives of the legends. My life was part of the legend.

But I was close now. I could practically feel her breath on me. Or was that just the wind?

Now I’ve got to get something straight with you. I was a skeptic, too. I wasn’t sure if there was a Bigfoot out there. That’s why I was in the woods to begin with, tracking for answers. I needed to know.

I put away the half-eaten sandwich and shouldered my pack. I followed the howling with squinty eyes. I walked as quickly and quietly as I could. My hands trembled. The wind blew around me in waves. I clutched my shotgun with swollen fingers.

How could it howl for so long? The sounds came in such excruciatingly long stretches. This thing must have huge lungs, I thought.

Then, after my foot stupidly snapped a twig, the howling faded away into the wind. Now I ran. I ran in the direction I thought the sound had come from. I ran like a jackass, my legs bucking under me, my body just along for the ride. This part I remember only as a blur. I remember seeing more and more moss. Then the moss was replaced with clumps of lichen. And then my lungs clenched like there were fists around them. I stopped running. I panted.

The woods had grown shadowy.

Where was I running to? If you ask me, I’m lucky that I didn’t find Bigfoot then. She surely would have gotten the jump on me.

I spun around, peering through the trees wildly. An icy sweat held the goosebumps at bay, but I shivered anyway. And my legs weakened: I was lost. My insides flinched. I’m lost.

I had had the foresight to leave my driver’s license on the dash, but not the foresight to bring a compass or a map. Hell, these were my backwoods, practically my backyard. How could I get lost in them?

And there were real things to worry about — screw Bigfoot — real things that were more than legends. There were grizzly bears and cougars and moose. I’m not sure what a moose could do, but I bet a moose would have had its way with me just then.

That’s when I saw it. Not Bigfoot. Only the strangest-looking tree I’ve ever seen.

Its lifeless limbs reached out into the air, holding shiny bunches of snow in their crooks. Its bark had probably been eaten by elk and deer during some particularly nasty winter, because its white innards were exposed. And there was a splintery hole in the middle of it. Lichen lolled out of this hole like a tongue. Two trees had fallen right next to it, their branches stretching yearningly across the ground and over the useless roots of the first one.

I smiled at this tree. At the very least, its absurdity framed my own. It was something I could talk about when I got back.

The adventurous spirit had finally run out of me. I was just a tired idiot lost out in the woods; another Bigfoot hunter stumbling over his own shadow. I had “stupidity in spades.” My wife — as with every idiot’s wife — was right as usual.

I sat down, rested against a tall pine, and stared at that odd tree. I retrieved the peanut butter and jelly sandwich and wolfed it down.

I peered out from under heavy eyelids: 9:02.

Sleeping out here is a horrible idea, I told myself. I might just as well shoot her in the toe and then climb into her arms to see how she’d react.

No. I shouldn’t have slept out there and I did my best not to. But every time my mind resolved to get up, my body lacked the energy. I was weighted down with cold, fatigue, and mounting fear. The last thing I can remember thinking that evening was, I wonder if there are any bats in that tree. After that thought, it was all just sensation and memories.

The temperature dropped as I drifted towards an unrewarding sleep, dropped far below freezing. Darkness crept into the forest and lurked through the trees. I don’t think it ever gets quite as dark out in the open — not by Deadfall Lake, anyway, not as dark as it got out there on the tree-covered mountain. I can remember playing as a kid late into the night, playing by the quiet waters of good old Deadfall. My brothers and I had stayed out so late, telling wild stories and scaring each other.

I slept.

I woke to the howling — the howling, practically in my ear.

My eyes had trouble adjusting to the darkness. And for those few seconds, it was all I could do to keep from pissing my pants. The adjustment made things look unreal, made the darkness stretch in places it shouldn’t have stretched. It made hairy arms out of branches.

There were no hairy arms, though. There wasn’t even a whisper of howl.

“Stupidity in spades,” Samantha said from somewhere inside me. “There’s no medication for that, you know?”

I clawed at the ground, trying desperately to find my shotgun. But the darkness was thick and heavy, like I was under icy black water; I couldn’t see anything. I tried to feel it out, but to my numb fingers, everything felt cold and smooth. My fingers finally closed over the barrel though, and I held the gun against my chest. I sat there, my back pressed hard against the tree trunk — so hard that the indentations from the bark would linger for hours.

Numbness like I had never felt climbed through me. It had already taken my fingers and hands, my toes and feet. Now it worked on my nose.

Still, there was no sound except for some pestering owl off in the distance. I waited to hear Bigfoot’s bellow again. I waited to feel her sticky breath against my skin.

Now and again — just as I would start to let my guard down, it seemed — I would hear the faintest hint of her. And again, my body would go tight.

I tried to smell her. In any respectable Bigfoot legend, the animal stinks to high heaven — I couldn’t smell anything but cold. I had given up trying to see her. To my eyes, everything looked like her.

Then, about an hour before dawn, the howl came full force again. And now I did piss my pants. I screamed right back in a high, waspy voice. A sharp wind tangled my hair and ran through the trees. And I pulled the trigger on my shotgun. There was a soft, dry snap, like a tree branch splintering in two. A misfire.

And suddenly I knew the howling. It wasn’t Bigfoot. It wasn’t a bear, or a cougar, or a moose. It was that damn tree, that odd-looking tree. The wind had caught in it and gotten all riled up, making those howling noises.

I sat, still shaking, dropping the shotgun down onto my legs.

My last thought before falling asleep was funny; only the stupidest of bats would hide in that tree. And Samantha’s voice came to me again, “So, I guess if you were a bat, that’s where you’d be.” She followed that remark with a little laugh, and I laughed, too. Then — abruptly as anything if I remember it right — I fell asleep again.

I still jittered the next morning though. Snow tumbled from the sky and frosty piss clung to my jeans. And when Teddy found me, he said that I looked like I had seen a ghost, like I had seen Bigfoot.

The snowflakes melted on Teddy’s nose, but seemed right at home on mine. My nose would be fine though. So would my fingers. The doctors would be able to save everything except the pinkie toe on my right foot.

“God, Frank,” Teddy said, “Samantha’s so freaking worried. You’re lucky I’m a better tracker than you.” A pause, then: “Did you see her?”

He was all talk that morning. I wasn’t: I shook my head, no.

“Are you sure?”

As if I wasn’t. What kind of a question was that? Was I sure? Of course I was sure. The idiot didn’t even notice the tree.

“So what did you see?” he asked, eyes as bright as lamps.

“You don’t need to know.”

Not as it May Seem, art by Aaron Wilder

Color, Forms and Family

Brenda Boboige

July, 1976. My five-year-old self sits at the backyard picnic table, floating on a sea of green grass. Sap from a hovering pine tree drips like thick sugar rain on my cheap timber island. My spindly legs dangle from a shaky plank of bench as I open the veritable treasure chest in front of me.