Capable of Cruelty

Maria D’Alessandro

In the last row of flexible, composed ninth graders, Susan danced self consciously. Her breathing came quickly as if she was being chased, but the only thing following her were the eyes of the audience. As she moved, she couldn’t remember what in the world had made her think she liked dancing. Her body was pink and her movement clumsy, but not wholly unattractive. The same friends who had convinced Susan to take the dance class with them, who had listened to the same Janet Jackson song ad infinitum in her basement and applied their own make up onto her lips and eyes, since she didn’t have any of her own, became her harshest critics on the day of the recital. ‘You forgot to smile,’ Erin said. ‘You kept looking down at your feet,’ Christine scolded. They were right, Susan did not want anyone to see her dancing. Against Christine’s advice, Susan positioned herself directly behind Holly Petros. Holly was the kind of girl that boys couldn’t take their eyes off of. It didn’t matter if they were just staring, making cat calls, or shooting balls of wet paper at her. At least they knew who she was. Susan didn’t think any guys at her school even knew her name. However, to everyone’s surprise and against all odds, a truly momentous thing happened after the assembly that day. A guy, and not just any guy, but Robby Sullivan, who she had liked since the 6th grade, asked Susan out on her first date. In the last row of flexible, composed ninth graders, Susan danced self consciously. Her breathing came quickly as if she was being chased, but the only thing following her were the eyes of the audience. As she moved, she couldn’t remember what in the world had made her think she liked dancing. Her body was pink and her movement clumsy, but not wholly unattractive. The same friends who had convinced Susan to take the dance class with them, who had listened to the same Janet Jackson song ad infinitum in her basement and applied their own make up onto her lips and eyes, since she didn’t have any of her own, became her harshest critics on the day of the recital. ‘You forgot to smile,’ Erin said. ‘You kept looking down at your feet,’ Christine scolded. They were right, Susan did not want anyone to see her dancing. Against Christine’s advice, Susan positioned herself directly behind Holly Petros. Holly was the kind of girl that boys couldn’t take their eyes off of. It didn’t matter if they were just staring, making cat calls, or shooting balls of wet paper at her. At least they knew who she was. Susan didn’t think any guys at her school even knew her name. However, to everyone’s surprise and against all odds, a truly momentous thing happened after the assembly that day. A guy, and not just any guy, but Robby Sullivan, who she had liked since the 6th grade, asked Susan out on her first date.

The week before, when Lana Atkins broke up with Robby, Erin asked Susan what she would do if Robby asked her out. The other girls giggled and fell back onto Erin’s bunk beds in mock ecstasy. The week before, when Lana Atkins broke up with Robby, Erin asked Susan what she would do if Robby asked her out. The other girls giggled and fell back onto Erin’s bunk beds in mock ecstasy.

‘For real, do you think you’re ready to date a guy like Robby?’ Erin asked. Being asked a personal question directly, and in front of their entire group of friends, startled Susan. She looked down at the shredded laces of her shoes, and then up at Erin’s completely manicured and composed face, her pursed lips and round eyes. She thought that Erin was beginning to lose all the qualities that she loved. Last year they would have discussed important matters such as this behind the bushes, behind the apartment building that Erin’s mother rented out from her grandmother, or up in the oak tree in their front yard, throwing pebbles into the street and laughing at the possibility of growing up into one of the trendy, polished sluts they watched saunter down the streets, wearing jeweled flip flops and eating fro yo. Erin’s hair would have been down, with bangs hanging over her eyes, wearing shorts that came down almost to her knees because her mom always said, ‘Don’t ask for trouble, enough trouble will catch you without a formal invitation.’ The other thing her mom used to say, brushing hair out of her clear grey eyes, was, ‘Don’t ever date a man you can’t take in a fight, girls, because if it comes down to it, you want to be able to clean the floor with the twerp’. Now Erin was dying her hair from natural blond to platinum, shaving the hair off of every visible and non-visible surface of her body, and criticizing Susan for her naivete. It just wasn’t right for Erin to so purposefully become so ordinary and accepting of conventions like choosing the perfect concealer and growing apart from her best friend. ‘For real, do you think you’re ready to date a guy like Robby?’ Erin asked. Being asked a personal question directly, and in front of their entire group of friends, startled Susan. She looked down at the shredded laces of her shoes, and then up at Erin’s completely manicured and composed face, her pursed lips and round eyes. She thought that Erin was beginning to lose all the qualities that she loved. Last year they would have discussed important matters such as this behind the bushes, behind the apartment building that Erin’s mother rented out from her grandmother, or up in the oak tree in their front yard, throwing pebbles into the street and laughing at the possibility of growing up into one of the trendy, polished sluts they watched saunter down the streets, wearing jeweled flip flops and eating fro yo. Erin’s hair would have been down, with bangs hanging over her eyes, wearing shorts that came down almost to her knees because her mom always said, ‘Don’t ask for trouble, enough trouble will catch you without a formal invitation.’ The other thing her mom used to say, brushing hair out of her clear grey eyes, was, ‘Don’t ever date a man you can’t take in a fight, girls, because if it comes down to it, you want to be able to clean the floor with the twerp’. Now Erin was dying her hair from natural blond to platinum, shaving the hair off of every visible and non-visible surface of her body, and criticizing Susan for her naivete. It just wasn’t right for Erin to so purposefully become so ordinary and accepting of conventions like choosing the perfect concealer and growing apart from her best friend.

Even though Susan could never understand what Erin was thinking, Erin always seemed to read Susan’s thoughts. She knew, for instance, that Susan wanted badly to go out with Robby, but didn’t want to become the kind of girl Robby would go out with. When it was just the two of them, Susan would tell her the funniest secrets, fantasies she had about guys she liked, but, in reality, she knew that Susan wouldn’t act on her impulses. She wouldn’t go all the way with a guy just to make him like her: second base, third maybe, but only if he promised not to tell anyone. She didn’t want to be labeled a skank like Holly Petros. Deep down Susan was different. Her parents didn’t use profanity, and they didn’t tolerate dating, immaturity or lying. Her parents tried to protect her like a favorite bracelet, to be worn only on the safe streets, the same streets on which she had lived for her entire life. Even though Susan could never understand what Erin was thinking, Erin always seemed to read Susan’s thoughts. She knew, for instance, that Susan wanted badly to go out with Robby, but didn’t want to become the kind of girl Robby would go out with. When it was just the two of them, Susan would tell her the funniest secrets, fantasies she had about guys she liked, but, in reality, she knew that Susan wouldn’t act on her impulses. She wouldn’t go all the way with a guy just to make him like her: second base, third maybe, but only if he promised not to tell anyone. She didn’t want to be labeled a skank like Holly Petros. Deep down Susan was different. Her parents didn’t use profanity, and they didn’t tolerate dating, immaturity or lying. Her parents tried to protect her like a favorite bracelet, to be worn only on the safe streets, the same streets on which she had lived for her entire life.

Two weeks ago, Susan had told her parents she was going to sleep over Christine’s house, and she packed a change of clothes and a fake ID. They were going to take the ferry to the city, to go dancing at a club that the other girls frequented. On the drive to Christine’s house, her mother played Z100, her favorite radio station, and looked at her in the rearview mirror. Her eyes squinted at her daughter, not out of suspicion, but wonder. It was almost as if she could not recognize her. Susan got sick as soon as she arrived, and did not go to the club with the others. Instead, she watched Friends on TV and ate an entire bag of marshmallows, before falling asleep on the floor. When the girls got back, their frantic laughter woke Susan, but she pretended to be sleeping. They stepped over her pink and white pajamas and she wondered if they were pointing to her while they laughed, or if they didn’t notice her at all. Two weeks ago, Susan had told her parents she was going to sleep over Christine’s house, and she packed a change of clothes and a fake ID. They were going to take the ferry to the city, to go dancing at a club that the other girls frequented. On the drive to Christine’s house, her mother played Z100, her favorite radio station, and looked at her in the rearview mirror. Her eyes squinted at her daughter, not out of suspicion, but wonder. It was almost as if she could not recognize her. Susan got sick as soon as she arrived, and did not go to the club with the others. Instead, she watched Friends on TV and ate an entire bag of marshmallows, before falling asleep on the floor. When the girls got back, their frantic laughter woke Susan, but she pretended to be sleeping. They stepped over her pink and white pajamas and she wondered if they were pointing to her while they laughed, or if they didn’t notice her at all.

‘Of course you’d say yes if a guy like Robby, or any of his friends, for that matter, asked you out,’ Christine said. In grammar school Christine had been an A+ student and a teacher’s pet, but high school changed her priorities. You could tell by the way she combed her hair she wished she could be popular. ‘Of course you’d say yes if a guy like Robby, or any of his friends, for that matter, asked you out,’ Christine said. In grammar school Christine had been an A+ student and a teacher’s pet, but high school changed her priorities. You could tell by the way she combed her hair she wished she could be popular.

‘And what if Andy asked you out, Chris? What would you give to go out with him?’ Erin asked. ‘And what if Andy asked you out, Chris? What would you give to go out with him?’ Erin asked.

‘There isn’t a single freshman who would say no to Andy Breaks,’ Christine said with conviction, and the other girls agreed simultaneously. ‘There isn’t a single freshman who would say no to Andy Breaks,’ Christine said with conviction, and the other girls agreed simultaneously.

‘It’s not like we don’t have a choice,’ Susan said. ‘It’s not like we don’t have a choice,’ Susan said.

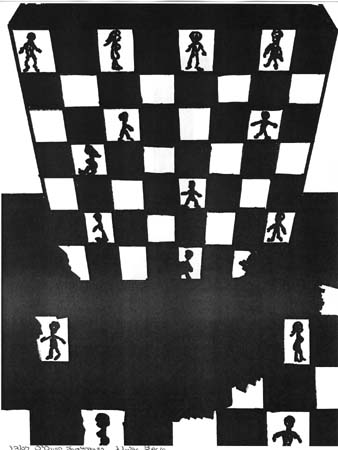

Usually, Susan kept her mouth shut when Christine put her down. Lately, Susan had to brace herself when she approached her peers: girls, boys, friends or enemies, it didn’t matter. She felt like she was always auditioning to be a character in a play that she hated. Still, she convinced herself that her friends just wanted to help her. Usually, Susan kept her mouth shut when Christine put her down. Lately, Susan had to brace herself when she approached her peers: girls, boys, friends or enemies, it didn’t matter. She felt like she was always auditioning to be a character in a play that she hated. Still, she convinced herself that her friends just wanted to help her.

The girls choreographed dances together in Susan’s basement, where adults wouldn’t venture to listen to their music or their words. Sometimes when she was dancing, Susan remembered why she liked the girls so much. Erin wasn’t afraid to make a fool of herself by twirling and leaping across the cold cement floor, singing, ‘I feel pretty, oh so pretty!’ When it was just the two of them, Susan actually displayed some rhythm and skill at dancing, even if she couldn’t be taught routines or stage presence. She couldn’t help thinking that if she could only look and dance the way Erin and Christine instructed her, that maybe she could win Robby’s interest. The girls choreographed dances together in Susan’s basement, where adults wouldn’t venture to listen to their music or their words. Sometimes when she was dancing, Susan remembered why she liked the girls so much. Erin wasn’t afraid to make a fool of herself by twirling and leaping across the cold cement floor, singing, ‘I feel pretty, oh so pretty!’ When it was just the two of them, Susan actually displayed some rhythm and skill at dancing, even if she couldn’t be taught routines or stage presence. She couldn’t help thinking that if she could only look and dance the way Erin and Christine instructed her, that maybe she could win Robby’s interest.

In the past few months, Robby went from being a class clown to ‘the man’. He had hazel eyes and big ears that stuck out a little too far, and his laughter was affectionate, never mean, like other boys’. Even a girl like Susan could picture Robby liking her. In the past few months, Robby went from being a class clown to ‘the man’. He had hazel eyes and big ears that stuck out a little too far, and his laughter was affectionate, never mean, like other boys’. Even a girl like Susan could picture Robby liking her.

When he asked for her number, his eyes didn’t meet hers. Then, when he called her, his voice sounded different, older and much more confident. He said, ‘My friends keep telling me they think you’re hot.’ When he asked for her number, his eyes didn’t meet hers. Then, when he called her, his voice sounded different, older and much more confident. He said, ‘My friends keep telling me they think you’re hot.’

Susan was so nervous talking to him on the phone that she didn’t suspect a thing. Susan was so nervous talking to him on the phone that she didn’t suspect a thing.

A Jeep pulls up in front of her house at 6:00. When she sees Andy, and not an actual adult, in the drivers seat, she begins to have second thoughts. (What is she expecting anyway, for Robby’s dad to take them out?) She suppresses the urge to look back at her parents’ house, and hops right in. She hasn’t told her parents, who think 14 is too young to date. The only people who know are the kids from school. Just the idea of her secret makes her feel more grown up, sexier even. She concentrates on the look of surprise on Christine’s face when she told her where she is going tonight. ‘Well, I guess our little girl is all grown up,’ Christine said. A Jeep pulls up in front of her house at 6:00. When she sees Andy, and not an actual adult, in the drivers seat, she begins to have second thoughts. (What is she expecting anyway, for Robby’s dad to take them out?) She suppresses the urge to look back at her parents’ house, and hops right in. She hasn’t told her parents, who think 14 is too young to date. The only people who know are the kids from school. Just the idea of her secret makes her feel more grown up, sexier even. She concentrates on the look of surprise on Christine’s face when she told her where she is going tonight. ‘Well, I guess our little girl is all grown up,’ Christine said.

‘Hi Chicken,’ Vein calls. ‘Hi Chicken,’ Vein calls.

Susan doesn’t see Robby right away. Instead there is Andy, Brian and Vein. Vein calls all girls chickens, so Susan tries to calm the pacing in her chest, and she hopes the boys can’t sense her fear. She thinks she can smell something like a skunk, maybe pot. Christine said that pot smelled like a wet dog sometimes. Susan doesn’t see Robby right away. Instead there is Andy, Brian and Vein. Vein calls all girls chickens, so Susan tries to calm the pacing in her chest, and she hopes the boys can’t sense her fear. She thinks she can smell something like a skunk, maybe pot. Christine said that pot smelled like a wet dog sometimes.

Robby appears from the back seat, holding a bottle of dark colored liquid. Robby appears from the back seat, holding a bottle of dark colored liquid.

‘Robby, what’s going on?’ she manages to say with a smile, though she looks like she is about to cry. ‘Robby, what’s going on?’ she manages to say with a smile, though she looks like she is about to cry.

‘Here, have some of this,’ he says, eyes darting from her to the other guys. ‘Here, have some of this,’ he says, eyes darting from her to the other guys.

He looks apologetic, but only for a second. He looks apologetic, but only for a second.

Obligingly, Susan takes two sips of ‘Puerto Rican Rum 40% alcohol by volume,’ as Robby takes the seat next to her. Andy doesn’t wait for her to fasten her seatbelt before stepping on the gas. As she sits with her knees pressed tightly together she can feel her inner thighs sweating. She wishes she hadn’t chosen such a short skirt. Susan looks out the window, but she can barely see her parents’ blue and white house disappear. Obligingly, Susan takes two sips of ‘Puerto Rican Rum 40% alcohol by volume,’ as Robby takes the seat next to her. Andy doesn’t wait for her to fasten her seatbelt before stepping on the gas. As she sits with her knees pressed tightly together she can feel her inner thighs sweating. She wishes she hadn’t chosen such a short skirt. Susan looks out the window, but she can barely see her parents’ blue and white house disappear.

Susan is too nervous to look at Robby, whose leg is twitching next to hers, kind of like her dad’s leg would twitch at the dinner table, like he wasn’t sure if he was coming or going. Susan is too nervous to look at Robby, whose leg is twitching next to hers, kind of like her dad’s leg would twitch at the dinner table, like he wasn’t sure if he was coming or going.

‘Take off your jacket and stay awhile,’ Andy says. ‘Take off your jacket and stay awhile,’ Andy says.

Andy’s a junior, but he seems even older than 17. He has two visible tattoos, one of a cross with some kind of swords going through it, the other a tribal band that rides the muscles of his right biceps. Andy’s a junior, but he seems even older than 17. He has two visible tattoos, one of a cross with some kind of swords going through it, the other a tribal band that rides the muscles of his right biceps.

Suddenly, the Jeep skids to a halt. Susan gasps and lunges forward, and Robby puts his arm out to catch her. Suddenly, the Jeep skids to a halt. Susan gasps and lunges forward, and Robby puts his arm out to catch her.

‘Look at this fat bitch, she almost made me hit her,’ Andy exclaims. ‘Look at this fat bitch, she almost made me hit her,’ Andy exclaims.

‘Hey, fat ass, watch where you’re going!’ Andy calls out the open window, and the guys in the back seat whistle mockingly. ‘Hey, fat ass, watch where you’re going!’ Andy calls out the open window, and the guys in the back seat whistle mockingly.

Susan peers out her window to see the girl that Andy is talking to. Susan’s face turns red and the heat permeates from her forehead all the way into her chest. Sometimes, Susan thinks that she might hate girls. Why else would she let the boys say those things? Why else would she laugh? What if Susan were the girl out in the street - what would Andy say to her? Then, she realizes that she is not like the girl in the street. She is the girl sitting in a car full of guys, after all. Susie starts to feel good. Her knees relax and she puts a brave hand on Robby’s leg. Susan peers out her window to see the girl that Andy is talking to. Susan’s face turns red and the heat permeates from her forehead all the way into her chest. Sometimes, Susan thinks that she might hate girls. Why else would she let the boys say those things? Why else would she laugh? What if Susan were the girl out in the street - what would Andy say to her? Then, she realizes that she is not like the girl in the street. She is the girl sitting in a car full of guys, after all. Susie starts to feel good. Her knees relax and she puts a brave hand on Robby’s leg.

‘Where are we going, anyway?’ She flips her perfectly straight hair a little when she speaks. Her lips feel moist, and she wonders if the other guys are watching her. ‘Where are we going, anyway?’ She flips her perfectly straight hair a little when she speaks. Her lips feel moist, and she wonders if the other guys are watching her.

‘To the fair out by South Beach,’ Robby answers, passing her the bottle again. ‘To the fair out by South Beach,’ Robby answers, passing her the bottle again.

By the time they arrive, Susie finally knows what it feels like to be tipsy. The fair, which to most people would seem drab and unimpressive, strikes Susie as the most magical place she has ever seen in Staten Island. It’s all lit up, orange, blue and yellow. The popping and whooshing of arcade games, the crank and screech of Ferris wheels turning, and above all the laughter, which nearly drowns the mechanical noises out, give Susie the sense that anything is possible. This is what she has been waiting for, preparing for, for her entire life. Robby seems to really like her. Wait until she tells the girls about this. Each of the guys brings her something. Brian gets her a beer. Vein gets her a choker with a rhinestone in the middle. Robby even wins a little purple stuffed bear for her at the ball toss. She clutches it like the prize that it is, and lets him put his arm around her waist. The colors of the tents and the flashing game stations remind Susie of the ‘twinkle’ setting of Christmas tree lights. When Susie takes a deep breath to calm her nerves, she is overwhelmed by the odor of French fries and, more subtly, salt. These smells, and the awkward touch of Robby’s fingers on her bare hip, make her giddy and she can’t control her laughter. When she looks around, it seems to Susie that boys are everywhere. By the time they arrive, Susie finally knows what it feels like to be tipsy. The fair, which to most people would seem drab and unimpressive, strikes Susie as the most magical place she has ever seen in Staten Island. It’s all lit up, orange, blue and yellow. The popping and whooshing of arcade games, the crank and screech of Ferris wheels turning, and above all the laughter, which nearly drowns the mechanical noises out, give Susie the sense that anything is possible. This is what she has been waiting for, preparing for, for her entire life. Robby seems to really like her. Wait until she tells the girls about this. Each of the guys brings her something. Brian gets her a beer. Vein gets her a choker with a rhinestone in the middle. Robby even wins a little purple stuffed bear for her at the ball toss. She clutches it like the prize that it is, and lets him put his arm around her waist. The colors of the tents and the flashing game stations remind Susie of the ‘twinkle’ setting of Christmas tree lights. When Susie takes a deep breath to calm her nerves, she is overwhelmed by the odor of French fries and, more subtly, salt. These smells, and the awkward touch of Robby’s fingers on her bare hip, make her giddy and she can’t control her laughter. When she looks around, it seems to Susie that boys are everywhere.

Just as Susie is beginning to wonder what time it is and if she should be getting home, Andy says, with what sounds like finality, ‘Let’s take a walk.’ Just as Susie is beginning to wonder what time it is and if she should be getting home, Andy says, with what sounds like finality, ‘Let’s take a walk.’

That’s when she realizes that Andy is not laughing anymore. He holds her arm tightly, and Robby lets her go. That’s when she realizes that Andy is not laughing anymore. He holds her arm tightly, and Robby lets her go.

‘Listen, is it getting kind of late? Maybe we should be heading home? Robby?’ she stutters. ‘Listen, is it getting kind of late? Maybe we should be heading home? Robby?’ she stutters.

‘You wanted to have fun tonight, right?’ Andy says. His voice gets increasingly lower and more serious, until suddenly he’s become an angry man. ‘You wanted to have fun tonight, right?’ Andy says. His voice gets increasingly lower and more serious, until suddenly he’s become an angry man.

‘‘I see you staring at me sometimes. You’re not so different from the other girls.’ Susie is beginning to wonder what she did wrong. ‘‘I see you staring at me sometimes. You’re not so different from the other girls.’ Susie is beginning to wonder what she did wrong.

He starts pulling at her clothes, and the other guys start in too. Everyone except Robby. Where is Robby anyway? She searches for him, but he’s gone along with the carnival - out of sight. The Ferris wheel is the size of a quarter and only the faint music of laughter reaches her ears. He starts pulling at her clothes, and the other guys start in too. Everyone except Robby. Where is Robby anyway? She searches for him, but he’s gone along with the carnival - out of sight. The Ferris wheel is the size of a quarter and only the faint music of laughter reaches her ears.

‘Susie, I’m sorry to be the one to tell you, but Robby doesn’t like slutty girls.’ Vein adds, following her gaze. ‘Susie, I’m sorry to be the one to tell you, but Robby doesn’t like slutty girls.’ Vein adds, following her gaze.

Everything is in a blur. Andy spits and curses, and the other guys laugh loudly, as if this is some kind of a game. ‘That’s just the way boys are,’ Susie hears in her mind. Then, Susie feels a cold finger between her legs: Andy’s fat cold finger, with a ring that presses against her flesh like a dull knife. Everything is in a blur. Andy spits and curses, and the other guys laugh loudly, as if this is some kind of a game. ‘That’s just the way boys are,’ Susie hears in her mind. Then, Susie feels a cold finger between her legs: Andy’s fat cold finger, with a ring that presses against her flesh like a dull knife.

‘Robby!!!’ She cries, before Andy pushes her hard and she can feel everything slipping out from beneath her. ‘Robby!!!’ She cries, before Andy pushes her hard and she can feel everything slipping out from beneath her.

She hits the sand and it is colder than she would have expected. She can hear the whirring of the sea. She feels like she cannot make a sound, so she is startled to realize that she is screaming. She hits the sand and it is colder than she would have expected. She can hear the whirring of the sea. She feels like she cannot make a sound, so she is startled to realize that she is screaming.

Then, there are flashlights and a booming dark voice. It must be cops. Susie can hear the words ‘assault’ and ‘under-aged’ as she gets up and starts running. The police don’t come after her. Then, there are flashlights and a booming dark voice. It must be cops. Susie can hear the words ‘assault’ and ‘under-aged’ as she gets up and starts running. The police don’t come after her.

The next thing she sees is Robby stepping out from behind the bathhouses, which means they are on the public beach. Susie realizes they are at least two miles from the carnival. Robby stops her. The next thing she sees is Robby stepping out from behind the bathhouses, which means they are on the public beach. Susie realizes they are at least two miles from the carnival. Robby stops her.

‘Where’s the fire?’ he asks. ‘Where’s the fire?’ he asks.

Susie glares. Susie glares.

‘Listen, I didn’t want that to happen. I didn’t know they were going to get like that. I called the police, ok?’ He’s talking so fast that he practically spits the words. ‘Listen, I didn’t want that to happen. I didn’t know they were going to get like that. I called the police, ok?’ He’s talking so fast that he practically spits the words.

There are two other guys with him now. They are looking at her in such a way that Susie realizes how drunk and insignificant she must seem. She starts to feel grateful that Robby is even talking to her. There are two other guys with him now. They are looking at her in such a way that Susie realizes how drunk and insignificant she must seem. She starts to feel grateful that Robby is even talking to her.

‘Jack has his dad’s car; he can drive us home okay? You could come by, hang out for a while...’ ‘Jack has his dad’s car; he can drive us home okay? You could come by, hang out for a while...’

Her eyes lift hopefully, but her body tells her to turn her back on the boys and keep running. As she runs red tears stream down her face, and she can’t get the sound of the boys’ laughter out of her mind. Her eyes lift hopefully, but her body tells her to turn her back on the boys and keep running. As she runs red tears stream down her face, and she can’t get the sound of the boys’ laughter out of her mind.

She keeps thinking,‘That’s just the way boys are.’ Where did she hear this phrase before? Then she remembers, without really wanting to. She keeps thinking,‘That’s just the way boys are.’ Where did she hear this phrase before? Then she remembers, without really wanting to.

Two years ago, Susan was hiking with her parents in the Catskill Mountains. It was the beginning of winter, and there was a thin layer of snow on the ground. The view at the fire tower was breathtaking. Everything was so quiet; she sensed a peace, a calmness that was abnormal in her family. There was a cabin, where campers could stay in the summer. Susan was curious and tried to open the door, but it was bolted shut. The wood was cold against her chapped hands. Under the handle there was something scratched into the wood. It read ‘Please stop I’m begging you Please don’t hurt me anymore Mama.’ Two years ago, Susan was hiking with her parents in the Catskill Mountains. It was the beginning of winter, and there was a thin layer of snow on the ground. The view at the fire tower was breathtaking. Everything was so quiet; she sensed a peace, a calmness that was abnormal in her family. There was a cabin, where campers could stay in the summer. Susan was curious and tried to open the door, but it was bolted shut. The wood was cold against her chapped hands. Under the handle there was something scratched into the wood. It read ‘Please stop I’m begging you Please don’t hurt me anymore Mama.’

It wasn’t until they were back at home in the kitchen, trimming a chicken and chopping onions, when she finally had the courage to tell her mother about the etching on the wooden door. Her mother laughed and said, ‘It was probably some mean teenage boys who wrote that, just to scare you.’ How do you know?’ Susan asked. ‘That’s just the way boys are,’ her mother answered. It wasn’t until they were back at home in the kitchen, trimming a chicken and chopping onions, when she finally had the courage to tell her mother about the etching on the wooden door. Her mother laughed and said, ‘It was probably some mean teenage boys who wrote that, just to scare you.’ How do you know?’ Susan asked. ‘That’s just the way boys are,’ her mother answered.

Susan finds herself alone on the beach. There are still a few people on the horizon laughing, innocent people who don’t know her. Susan finds herself alone on the beach. There are still a few people on the horizon laughing, innocent people who don’t know her.

She takes a path that separates a patch of trees from the water. There are a couple of men alone, smoking. There is a desperation in the distance they place between themselves and civilization. Standing in the shadows, they look like ghosts or murderers. She tries not to make eye contact. She pushes down fallen reeds with her feet, and they sink into the mud. Mud cakes on her Mary Janes. It’s not as beautiful here as it used to be, she thinks. Then again, she’s never been here. She hardly goes to the beach at all, but remembers it fondly. It’s beautiful, with skin colored sand and the romantic sounds of the ocean crashing into your thoughts and washing them away. It’s lovely at the beach. She thinks she will feel better, cool off, once she disappears into the bank of the anonymous shore. She takes a path that separates a patch of trees from the water. There are a couple of men alone, smoking. There is a desperation in the distance they place between themselves and civilization. Standing in the shadows, they look like ghosts or murderers. She tries not to make eye contact. She pushes down fallen reeds with her feet, and they sink into the mud. Mud cakes on her Mary Janes. It’s not as beautiful here as it used to be, she thinks. Then again, she’s never been here. She hardly goes to the beach at all, but remembers it fondly. It’s beautiful, with skin colored sand and the romantic sounds of the ocean crashing into your thoughts and washing them away. It’s lovely at the beach. She thinks she will feel better, cool off, once she disappears into the bank of the anonymous shore.

She is wrong. She feels the dirt inching up her ankles, and spots all kinds of unwanted things around her: a few Bud bottles, candy wrappers, a popped balloon. She drops the purple bear she has been holding. She is wrong. She feels the dirt inching up her ankles, and spots all kinds of unwanted things around her: a few Bud bottles, candy wrappers, a popped balloon. She drops the purple bear she has been holding.

She keeps going, hoping to find a sign, something that she can relate to good memories, a piece of whatever is making those other beach goers happy. She’ll be okay, she thinks, turning it over in her mind. Nothing really happened. It was just a bad joke. She wonders for a moment how she will get home, and if Robby might still answer his phone. She keeps going, hoping to find a sign, something that she can relate to good memories, a piece of whatever is making those other beach goers happy. She’ll be okay, she thinks, turning it over in her mind. Nothing really happened. It was just a bad joke. She wonders for a moment how she will get home, and if Robby might still answer his phone.

Pink and dark blue bruises encircle the moon. She bends over to test the water. It shouldn’t be so cold. Just then, she slips and begins to fall, but catches herself on the rocks. As she recovers her balance, her hand grazes something hard and striated. It’s bone. Taking in the scene slowly, Susan sees another skull next to the first, and then another at her feet, and another a few inches away. What could they belong to? Dogs, deer, rabbits? The elevated skulls are facing each other, as if in the vows of matrimony. She feels the sweat on her body turn icy, the way it does before fainting. Involuntarily, she runs her hands over the one with horns. She feels it before she can see what used to be: a goats face, the place where its eyes, nose, and mouth had been. Who would do this? Pink and dark blue bruises encircle the moon. She bends over to test the water. It shouldn’t be so cold. Just then, she slips and begins to fall, but catches herself on the rocks. As she recovers her balance, her hand grazes something hard and striated. It’s bone. Taking in the scene slowly, Susan sees another skull next to the first, and then another at her feet, and another a few inches away. What could they belong to? Dogs, deer, rabbits? The elevated skulls are facing each other, as if in the vows of matrimony. She feels the sweat on her body turn icy, the way it does before fainting. Involuntarily, she runs her hands over the one with horns. She feels it before she can see what used to be: a goats face, the place where its eyes, nose, and mouth had been. Who would do this?

She drops the dead thing, and looks around her for something or someone. There is no one to tell. She drops the dead thing, and looks around her for something or someone. There is no one to tell.

Susan straightens herself up and begins to walk away from the beach towards the main road. Completely sober now, she finds her way from the boulevard to roads that she can identify. As she gets closer to home she does not recognize her neighborhood. The once orderly, pleasant gardens, guarded by newly built fences, now seem oppressive. The tall, similarly shaped and colored houses now look like boarded up shacks with signs that read ‘Do not Enter.’ Streets where white middle class families build fences and hang flags, signifying not unity but exclusion. Streets where the height of green grass and the site of red white and blue is as predictable as divorce, or violence during hard times. Everything, from the neighbor walking her dog to the blue and white molding on her parents’ two story house, seems capable of cruelty. Susan straightens herself up and begins to walk away from the beach towards the main road. Completely sober now, she finds her way from the boulevard to roads that she can identify. As she gets closer to home she does not recognize her neighborhood. The once orderly, pleasant gardens, guarded by newly built fences, now seem oppressive. The tall, similarly shaped and colored houses now look like boarded up shacks with signs that read ‘Do not Enter.’ Streets where white middle class families build fences and hang flags, signifying not unity but exclusion. Streets where the height of green grass and the site of red white and blue is as predictable as divorce, or violence during hard times. Everything, from the neighbor walking her dog to the blue and white molding on her parents’ two story house, seems capable of cruelty.

She looks down at her hands and her feet; they are covered with sand and spots of dried mud. She feels her knees shaking and runs a hand over the goosebumps, covering her bones. Susan thinks of Erin and Christine, but imagines the way they looked in grade school. It’s as if her mind has taken a picture of what the girls looked like when they were still best friends. She shudders to think what Christine would say to her now. ‘So you thought they really liked you? You thought you were one of them...’ She looks down at her hands and her feet; they are covered with sand and spots of dried mud. She feels her knees shaking and runs a hand over the goosebumps, covering her bones. Susan thinks of Erin and Christine, but imagines the way they looked in grade school. It’s as if her mind has taken a picture of what the girls looked like when they were still best friends. She shudders to think what Christine would say to her now. ‘So you thought they really liked you? You thought you were one of them...’

‘When really you’re left standing outside, completely alone.’ Susan says, breaking the silence. ‘When really you’re left standing outside, completely alone.’ Susan says, breaking the silence.

|