|

Order this writing in the collection book Unlocking the Mysteries available for only $1795 |

|

|

| |

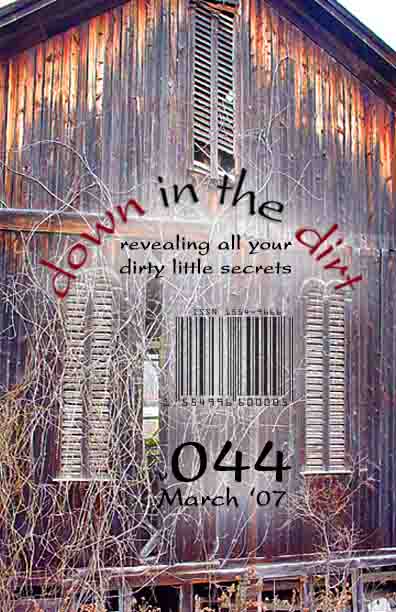

This appears in a pre-2010 issue

|

|

|

|

| ||

Mules and Mules

Ben Orlando

In the end it wasn’t the heat or the sweat that dripped out of his skin from a thousand leaky faucets. It wasn’t his heart or the thirst or the precarious position in which he found himself, balanced atop a wobbly mule with a thick piece of hemp wrapped around his neck.

It was his voice, nonstop and penitent, and it was my hand, my fingers pushing against the rump of the ass that silenced him for good.

I guess I’m writing this because I’m trying to perform my own sort of penance. But this way, at least, if you don’t want to hear me, you don’t have to listen.

We were together, he and I, for a couple of weeks, and they saw us together, at the diner, our interactions. It was only a few minutes, but it was enough for them to read the vibe, for them to learn me up and down. They knew me better than I knew myself, because I like to pretend. I like to pretend that I’m stronger than I really am, that my will is great and my resolve steadfast. I don’t think he knew, but they did. They followed us home.

Home: a ten-dollar-a-night motel with stains that would crack the lens of a blue light-stains that I can feel all around me right now without any technical assistance. The last rentable shower and lumpy mattress for the next hundred miles. The closest thing to an oasis on the fringe of society.

I met him, Jackson, on the concrete, three in the afternoon with the sun burning holes in my work boots, both of us waiting under the sliver of awning on the Palo Verde Funeral Home, waiting for our first assignment. That was three weeks ago.

I don’t know his deal, what he was all about, except that he was a drifter, place to place, job to job like me. But he hinted at prison time. I never pressed it, though I think he wanted me to.

His lip always curled up to the right when he got close to spilling it; curled right under that speckled orange mustache. When he said things like “But I wasn’t around to see that,” or “and I would have gone to the game but I was (lip curl) otherwise engaged.” And his mustache, his orange eyebrows and his reddish orange hair and white, white skin were other indications of his state of mind.

He told me four or five jobs he’d had in the past, all eight to ten hour gigs busting a gut in the dry southern California sun, and there in the parking lot on our first day I could see the skin on his forearms peeling away, bubbling, minute by minute as he talked.

But he didn’t talk about that. I didn’t press it.

I’m the quiet type. I like to write things down. I’m a writer, I guess, but if I call myself that I’d have to attach “failed” to the front, kind of like a bunch of pallbearers leading the casket out to the hole.

It’s the only thing I’ve ever done, and it’s kept me from a steady job and a normal life, but not doing it well has kept me from security, from avoiding near-fatal jams.

I’d heard about the rackets, the rumors of the things that go down in Palo Verde, in the homes and parlors.

Something about taxes, something about drugs, but like most things you here, the words kind of died on their way to my better judgment. It was a job: digging holes, dragging bodies, dumping bodies and dumping dirt over top for twenty dollars an hour. No families present. No explanations. Who questions that? No one applying for that kind of job, that’s for sure, and whether Jackson knew about it from the start I never learned. I don’t think it would have mattered.

We’d always wait in the lot for the bodies, and the guys that met us that day didn’t have a clue. In fact, they probably got theirs a little while after we left with the goods: a teenage Hispanic girl, pretty, and she must have been something. I mean, I don’t know if it’s sick to say, but they didn’t spend a lot of time fixing her face like they do with some folks.

You could tell by the coloring, the droop of the eyes, the vacant expression. Yet she was still pretty, even in that state, even inside of that bag. He pulled back the plastic a little. I wouldn’t have, but he was right. She was pretty, and that’s what started it, when he opened that bag.

It was twenty dollars an hour because we did it all.

We loaded the bodies, we transported the cargo, we dug the hole, dropped them in and covered them up. The whole package. Only us, all alone in the middle of a dusty plot.

When we got to the site, after we dug the hole and hauled the body out of the truck, when he tore the plastic back all the way down the seam, I got kind of scared, awkward scared, like I knew nothing was going to happen to me, but I thought that if I stood there and watched, witnessed what I thought he was going to do, I’d change, become someone different, maybe, like him. But he didn’t do it.

He opened the bag and ripped off her clothes, but that was it. Said he just wanted to see if the body was as good as the face. That’s when I took my first breath, and that’s when the white bubbles dribbled out from her lower portions. Like I said, I thought he’d spent some time behind bars. After what he did next, I had no doubt.

The finger, his right index finger, slid around inside his mouth for a minute, like he was trying to coat every part of his gums with it. Then he smiled and looked up at me, and walked to the truck.

Another mule, this time a different sort. She’d somehow slipped the noose of her employers only to die from an internal leak. We weren’t coroners, but that’s what we thought happened. Or she didn’t slip.

We slipped.

I helped cut her open. We used an Exacto knife from the glove compartment. A few years back I spent a summer gutting fish on the Oregon Coast. I told Jackson. He said it was the same thing.

He was good with the knife, didn’t cut any of the other bags, eight in all, not counting the one that leaked. We couldn’t salvage that one.

He held up each bag like the contents were sacred artifacts from the tomb of some Egyptian king. That’s when I got scared. I knew he wouldn’t give them up, and people like this, I told him, don’t just forget about missing drugs, hundreds of thousands of dollars of missing drugs. But he wasn’t worried, and his complete lack of fear steered me into his court, though I was never fully convinced. Thankfully.

They must have overheard me at the diner trying to talk him out of it, trying to get him to leave the goods near the body or at the funeral home. That’s why I figure they only stabbed me, repeatedly; left me for dead under the Cottonwood tree. Under him. But they left me with some kind of chance. He was screwed from the start.

It was still light out when they jumped us at the motel, but nobody cared-a few eyes on the other side of the glass distracted for a moment from their cable TV. Nobody cared. We were outside of that part of the world.

I don’t know where they got the mule, the real mule, but on the way there I was more concerned with the turnout, bitter at the score, my four wounds to his none. But then I got it. I felt better, if you can feel any better, propped up against the cottonwood with a little more hope than the man teetering a few feet above me. As it turned out, I was almost as strong as I believed. But my patience was a bit lacking, and he was a big pussy.

I couldn’t have helped him if I’d wanted to, but after ten minutes of gapless dialogue he cleared up any internal conflict I might’ve been feeling. And twenty minutes after that, with the last of my strength, I leaned over as far as I could, buried thepain in my side and, with as much force as I could generate, slapped the back of the mule. And that was that, and fifteen minutes later a beet farmer, the only resident within eighty miles, spotted us from his brown Cherokee. He got a mule and I got my life back.

I guess I could have held out for a few more minutes. But then he might have lived, and feel-good’s not my kind of ending.

![]()