|

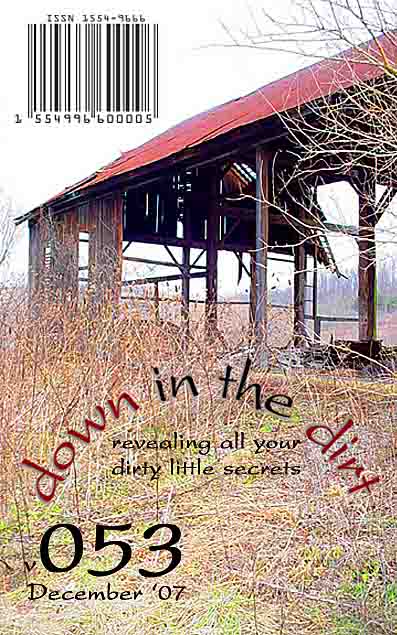

Order this writing in the collection book Revealing All Your Dirty Little Secrets available for only $1995 |

|

|

| |

This appears in a pre-2010 issue

|

|

|

|

| ||

The Volunteer

Pat Dixon

“So, young miss, you already have three college degrees, an’ now you’re working on your fourth one? Well, I won’t hold that against you—but I can’t speak for Roscoe here.”

Patrick Growel squinted at me and pursed his lips in what looked like an angry expression. Two big pussy cats! Two big, mostly toothless, old Toms! were my amused thoughts. I have no idea whether Roscoe, purring in Patrick’s lap with a gnarled, spotted hand kneading his neck, had been neutered, nor did I care to know. I did not speculate about Patrick’s sexuality either—and I trusted that he wasn’t thinking at all about mine. Because my work in the field demands it—both for comfort and to get along with “male native laborers”—and because I’d rather have my brain be the center of people’s attention, almost always I dress androgynously, with my hair tucked up and my figure—unrevealed.

“Roscoe’s one of the great cats,” I said. “He knows it, I know it, and he knows I know it. That makes me all right with him. And as long as he’s in a warm place, he doesn’t care a rat’s ass about any other kinds of degrees.”

I’d hoped my little pun or even my use of the word “ass” would provoke a smile or at least some other reaction from Patrick, but his expression did not change. He just slowly looked down at the tabby’s huge head, which he began scratching where its capital “M” is. Then, without looking up, he said, “Truer words were never spoken, young lady. She has your number, Ross, ol’ fella.”

His mouth stayed open at the end of that sentence, and I expected he would add a comment like “I guess there’s a little hope for her yet,” but he just wheezed a little and said nothing further.

“Can I fix you a cup of coffee, Patrick? Or a cup of tea? I saw you have a nice selection of tea out there in your kitchen. Any preference?”

He squinted over at me and after a long pause said, “Some of the licorice tea would be my preference—a whole pot of it. But I guess you could make us each a cup of instant coffee instead.”

“Why’s that? I’ll be happy to make a whole pot of tea. It’ll only take a minute or two more, using your microwave oven. In fact, licorice tea sounds like a flavor I’d like to sample.”

“Well—I guess, then, you could brew it up in a mixing bowl or something, young lady.”

“Diane,” I said, in case he had already forgotten my name. “You can call me Diane if you want to. Or call me ‘young lady’ if that suits you better. Whatever. So tell me, Patrick: just why a mixing bowl instead of a teapot? Did you have a teapot that got broken or something?”

I suspected that this was the case. Roberta Schwarz, my Hospice supervisor, had said that Patrick Growel would be a special problem for me for a number of reasons. Three days before when I got home from teaching, I found her message on my answering machine and called her back. She’d said she needed a one-time fill-in, because one of the other volunteers had come down with a cold and couldn’t go to his current patient on Friday afternoon from 1:00 to 4:00. She said that I was the only other volunteer who was free Friday afternoons and apologized profusely for giving me a male patient, something very rarely done with female volunteers. I’d told her I could take the case and would be happy to do so.

After Roberta gave me the patient’s name, address, phone number, illness, and prognosis, she added, “Diane, Patrick’s regular fellow—let me paraphrase so that I’m not revealing anything confidential here—the regular fellow seems to think that Patrick is a hostile old coot who is unresponsive—and bitter—angry. You might end up just—mmm—sitting across from him for three hours and never getting word one out of him. It could happen—and probably will. He has no known interests—cards, checkers, chess, Monopoly, or whatever. He doesn’t want to watch any daytime TV or want to have a newspaper read to him. He has a mangy old cat of some sort that he sometimes will let up on his lap. So, if it’s not going well, just feel free to make up a story about needing to be someplace else and just leave early. Do you have enough copies of the visitation forms, or should I mail you some more?”

I told her I was well supplied with forms—in fact, I added that whenever I run short, I just make extras off the copying machine where I work part time.

She thanked me for taking this assignment and apologized for sticking me with a grouch.

“Growel seems to be an appropriate name for him, Diane. Anyways, I’ll try to give you a sweet little old lady next time. Okay?”

“Make her black, Roberta, if you can, or Muslim. That would be my preference to try to increase human understanding in this sad crummy world of ours.”

She explained once again that such people seldom chose to become part of the Hospice program here, and I told her it was all the more reason to let me have them if and when they ever did. I know she thinks I weird, but sometimes weird is good.

But I digress. Patrick stared at the far wall towards the back of his little house for half a minute or so before answering me.

“Nope—Diane. The teapot didn’t get broken—at least not by me.”

“What happened, then?” I asked.

After another longish pause he replied: “I don’t want to accuse anybody of anything wrongly—but three weeks ago when that other fella—that Hospice guy who normally comes here, you know, was here—well—it wasn’t here after he left. I can’t say what’s become of it, but I haven’t had any tea since that day. Coffee is what I now make for myself—and what he and I have when he comes here—if he’s in the mood.”

“So you can’t make tea just by the cup?”

“Thrift. I’m on a limited income now, and I don’t want it to run out before I go, which they tell me won’t be long. I make six cups of tea with every bag. The pot held three cups each time, an’ I used each bag twice. But, for guests, I’d use two bags in the pot to make three cups.”

“Patrick, do you remember what I said I do—besides teach at Witherspoon part time, I mean?”

“Yes.”

“I’m an archaeologist—and you know what we archaeologists do for a living—at least part of the time, when we’re not making drawings and measurements and writing up our findings? Huh?”

“Course I do, young lady. I may not’ve finished high school, but I’ve had an education—plenty of ways to get that.”

“Of course your right. I was just trying to be a little playful—and kittenish. I don’t go around treating people with different backgrounds as dumb. But then you and I don’t really know much about each other yet, do we, so I can see where you might’ve thought I was doing that, okay?”

He looked down at Roscoe and suddenly wheezed a bit in a staccato manner for five or six seconds. At first I wondered if Patrick were having some sort of fit or something, but then I realized that this was just his way of laughing. When he looked up at me, he had a small grin on his lips and what might have been a small twinkle in one of his squinty eyes.

“Y’ dig stuff up,” he said.

“Perfect,” I said. “I’m going in there and make us some tea. I’ll be back shortly while it’s ‘baking’ in your oven. Would you like me to get anything for Roscoe while I’m in the kitchen?”

“Maybe two of those fish yummies up in the cupboard over the stove—the regular stove,” he said. “Would that be okay with my big boy?”

Roscoe made no reply but just watched me get out of the soiled stuffed chair and walk to the kitchen. He seemed to sense his food had been discussed, for he hopped off Patrick’s lap and followed me. Or perhaps he really wanted to make sure I didn’t steal anything while I was in there. I bent down and gave the top of his head a short scratch with my short nails, and he rubbed the side of his mouth against the knee of my jeans. Patrick seemed to take no notice of this flirtation between us.

In the kitchen, it took me only forty seconds to locate the teapot. It was a tall grayish thing with the spout being a cat’s right front leg, the handle being a cat’s tail, and the lid being a cat’s head. A small knob had been added to the bottom edge a little to the left of the spout, representing the other forepaw, and the whole thing was crudely painted as if by a young child. I looked inside and found a pair of nasty, moldy tea bags in a shallow brownish broth of nasty, moldy liquid.

After I disposed of the fungi and gave the pot a good scrubbing with some cleanser and ammonia that I found under the sink, I rinsed it five times with hot water. Then I dropped two yummies for Roscoe into his little bowl, and, holding the teapot aloft at shoulder height with both hands, I stood in the doorway to Patrick’s living room.

“Ta-da!” I said. He turned towards me and looked up, raising an eyebrow.

“Is this what I should make our tea in, Master?” I asked, tilting my head.

“Where did you find that?” he said.

“I could tell you I’m an archaeologist and excavated it from under some old letters and flyers and dish towels that are on your kitchen counter—but you wouldn’t believe me, so I’ll come clean instead, Patrick. I am a witch—or, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, a jinn or genie—but not quite the Barbara Eden type—a little bit weirder, maybe. I used magic, Patrick. This used to be Roscoe.”

Instead of playing along with my humor, Patrick said, “I guess that’s just one more sign I’m slipping. My niece has been saying so for the last four months. I guess this is a clear example.”

“Patrick, in some ways from the moment of birth all of us start slipping. That’s why I think it’s important to put out our hands to each other from time to time. I’m not a religious person, Patrick—I’m as secular as they come—but I still believe in the Golden Rule, which, by the way, was independently invented in at least six different ancient cultures as a basis for morality. So is this what we make our tea with—or do you want me to do it in a mixing bowl?”

“Use the pot—Diane—but be careful—please. My son made us that back when he was a kid, and I don’t want it to go before I do—if that’s at all possible.”

Widower. World War II vet. Lost his son in the Vietnam War. Lost his wife to cancer about twenty years ago. Only known relative is a niece that lives in Storrs and visits him about once a month to check his own cancer’s progress. I heaved a sigh and made us a nice pot of tea, noting the brand of licorice tea he used so I could send him a box anonymously in the mail.

“Other than that teapot of mine, what was the biggest find you’ve made so far, Diane?” he asked me after inhaling the vapors of his tea.

“Well, you know I’m not one of those tomb raiders like Indiana Jones or Lara Croft or such. What I do is try to find evidence for how people used to live long, long ago. In my case, I work in southern Mexico now, at a site that was abandoned about a thousand years before Columbus ever landed. My ‘biggest’ discovery was one day, on a level nobody expected it, I found a kind of platform made of mud bricks. Not a golden mask or a crystal skull or an emerald crown—just a plain ol’ platform of mud bricks. We don’t even have a clue what it was used for, but now we know those people were making ‘em—or at least made one of ‘em long before we’d previously thought they were. It could be an altar—or a workbench—or breakfast table. But I’m the one that found it, and the project director nearly expired on the spot from excitement. It was chiefly on that basis that he asked me to come back each year afterwards.”

“So—Diane—you’re still working on a doctorate, right? What is your—your topic for your—dissertation—about? Not that platform, is it?”

“No, no—not that platform—or even platforms in general. I’m doing pottery analysis. I get to classify the types of pottery we dig up—long hours of backbreaking work sorting thousands of basically smashed house-ware pieces by type and trying to set up a chronology based on where they were found and what else was near them—and their style, of course. Sometimes a style is copied for generations, diverging in a way like, say, evolution, into other styles. Or a new style may suddenly come in, either by a new potter having a hot idea, maybe, or by trade with outsiders, maybe, or a combination—a potter sees something in other people’s pots that he—or she—wants to adapt or adopt. And I’ve got permission now to use the collections of at least forty museums that have pots from that period and area as well as nearby areas of that period. It’s a huge thrill, I can tell you.”

Roscoe rubbed his lips against my knee again and then leaped onto my lap. Patrick smiled his first broad smile.

“Well, he was a one-man cat.”

“Patrick, Roscoe still is a one-man cat—but I know what you’re saying.”

“So—Diane—what do you want a doctorate for? Will it improve your income to have it?”

“Hmm. Good question. Probably not. It’ll probably make it harder for me to find a job, actually—especially as a teacher. I’ll be competing with people like me now, who don’t have a doctorate—and who are a dime a dozen-dozen. I’ll probably price myself out of the market. Most colleges are only hiring adjuncts now—that’s all I am at Witherspoon—an adjunct teacher. We’re just filling in because a real prof is on leave or out sick—or because they don’t have permission to hire a tenure-track person when somebody retires or—otherwise leaves—the slot—vacant.”

“Or dies,” he said, with a smile and a little snort. “You can say ‘dies’ around me. I’m not some frail chunk of pottery that’s going to crack at the word. Dying is one of the things that all of us do. Some sooner, some later. Some easily, some—not.”

“Would you like to talk about—dying—Patrick?” I asked.

“Not really. I just want my money to last till I go. I don’t want to be a burden to anyone. Not my niece—not the state of Connecticut—nobody. I’ve got the pain under control—pretty well. They told you I’ve got cancer of the liver? And it’s spread?”

I nodded.

“Good. The other fellow dances around and tries to be Little Mary Sunshine when he’s here. Says, ‘Who knows what cure could be discovered tomorrow?’ and all that horse hockey. An’ never uses the word ‘cancer.’”

He paused and looked down at his hands. I watched him and petted Roscoe, who was rumbling with a deep bass purr.

“Ol’ Ross likes his shoulders squeezed—gently, ‘cause he’s gettin’ old, too—an’ he likes the fur of his stomach gently tugged at, too. Anyways, getting back to what we were talking about, you know what I think?”

“No, I don’t. What?” I asked, expecting him to philosophize about the meaning of life and death.

“I think you should go to native potters down there in Mexico—and show them some of the broken pieces you’ve got. Can you do that?”

I shivered. What a change of topic. And yet it was what we’d been talking about before.

“I—yes, sure—I can do that. I’m in charge of the analysis, and I hang around our site after most of the others have left when our ‘digging season’ is done. There are four junior grad students I supervise and a couple of trained native helpers—yes, I could do that. But why?”

“Because a potter—a real potter that makes a living at something, not just a person with a hobby or who ‘took a college course in it’—will know stuff about how something was made and why it was done a certain way. Same with stone masons and brick masons—and carpenters—and weavers—and smiths.”

He let this sink in and gathered his thoughts and breath for the next statement he aimed at me.

“I quit high school and became a stone mason. I left my mark on five of the buildings there at Witherspoon back in the late ‘40s an’ early ‘50s, after I got out of the service. I used to be able to point to places on the stone faŤades that I myself laid down—and places that the head mason on the job did—and places that Jimmy Blount did—an’ two or three other fellas whose names I’ve forgotten. Each of us had a distinctive style, though to the untrained, unknowing layman’s eye it all looks the same. I could tell you where each of us ‘settled for’ something because we just were not able to do any better.”

My heart began to race. This sort of idea was news to me. I bit the insides of both my lips—gently, of course—and paid closer attention.

“Diane—have you ever walked around town and looked at the stone masonry? No? Well, if my eyes were still worth anything, and they ain’t, I could point out stuff to you that would make you laugh. Some of the older buildings, like that little granite thing beside the public library and the old garage diagonally across the intersection from it, go back to colonial days and are quality work—but not as good as I saw in Italy that the Romans had done two thousand years ago. Or in England during the middle ages! I just wish I’d been to Peru to see Inca work. Been to those places?”

I nodded. Yes, I had, but I hadn’t seen what he was now talking about.

“If a good stone mason is with you, he can point out stuff about the style of workmanship and can point out how much so-and-so did in a day and how many chief masons were on the job at any given point. The crap that is put up as a faŤade nowadays would make most real masons puke with disgust. It’s like the pie crust black top patches that the road crews lay down on pot holes every February and June—deliberately making something that won’t last so’s they’ll have another job to do in a little while. Most buildings nowadays are made to fall down in less than forty years, I think. Their faŤades are just the thinnest cosmetic things, slopped on with epoxy in some cases and bitumen in others—a lot like some people’s faces or personalities these days. Anyways, as far as nasty masonry is concerned, that was a problem that began during the Victorian age, young lady. And a Victorian guy name of Ruskin was fussing about it then in several of his books. You ever hear of him—John Ruskin?”

I shook my head no.

“Well, way back in my eighth-grade reader, which was probably printed during the dang Victorian age, we had a long essay by John Ruskin about Gothic architecture—an’ a lot more social comment on the side, so to speak. I liked what he said, and I made it my business to read more of him later—on my own. Quite a fella. You might want to look him up one day.”

I nodded, feeling a sudden tightness in my throat, touched by Patrick’s sudden passionate outburst about masonry and its styles and skill levels—things he obviously cared much about. And my mind was racing to the implications for my own field.

Patrick leaned forward suddenly, like some kind of water fowl about to grab a fish, and then stood up. He grinned at me.

“Never seen an old-timer get out of a stuffed sofa the right way before? I bet you thought I was going to pitch over on my head. No, not this time. Not yet. The dang seat cushion has no body to it. The other young lady at the rehab place—back when I had my surgery that disclosed what was what—she taught me five or six good tricks, ol’ dog as I am. Anyways, as Mr. Newton’s wet nurse must’ve told him, ‘What goes in, must come out.’ A fella needs to answer when Nature calls—or suffer the very gross embarrassment of something I can’t discuss in a lady’s company.”

Roscoe hopped off my lap and followed Patrick to his bathroom, perhaps expecting a side trip to the yummy box would be coming soon.

I leaned down and then stood up and stretched my back and arms. The ‘lean forward’ technique did indeed work. Without it, I would have had to press down on the arms of the chair to raise myself out of it—something I would have done without even thinking before Patrick educated me in the physics of standing.

I looked around his living room. Behind my chair was an old, scarred bookcase with an old set of books in red bindings. The works of John Ruskin, I saw. There must have been over thirty volumes in it. I was reading their titles when Patrick returned.

“Ruskin was a crazy duck in some respects, sorry to say, but a powerful genius in some others. Had what you might call a ‘quality-control problem’—like most of us.”

I nodded and sat down again, smiling with genuine interest.

“I’ve got—besides that old set of his writings—a couple of—of scholarly books about him and his times—I could let you have them, if you think you’d get to them. I know my own eyes will never get through them again.”

I started to speak, but he interrupted me.

“Diane—I know the other fella will be coming back again when he’s over his cold or whatever, an’ he’ll be my regular till he—till he finds out I’m gone—into a hospital or whatever. I’ll probably never see you again, nor you, me. I truly cannot read anymore. My niece knows the value of that set of Ruskin books and has her claws ready to scoop ‘em up—no, I mean it—she’s already asked if she could take ‘em now, before I’m gone, not even lying on the floor, cooling off.”

He coughed and laughed simultaneously so that I could not tell where one sound began and the other left off.

“Sorry. It amused me just now to think how she’d feel to find just one volume was missing from the set. If I can find that essay about ‘The Nature of Gothic,’ would you do me the favor—the courtesy—of taking that with you when you leave today?”

We’d been told it was all right to accept a beverage or a little snack from a patient, but we’d been strictly forbidden to accept any gifts from any. It could cause the Hospice program to be distrusted by patients’ relatives. Patients were often not in a “normal” frame of mind, either knowing they were dying very soon or just from experiencing, as a side effect of their approaching deaths, a decline in their abilities to make “sound” judgments. Much as I trusted that Patrick Growel was of sound mind, I knew that I would be doing the wrong thing to accept a book as a gift.

“No? I thought not. I’m still a pretty fair judge of people’s character, though I would have truly been glad for you to take it. Well, I know the rules as well as you. I don’t want to give it to that other fella on principle—even though I’m almost sure he would take it—just to oblige me—and would probably pitch it in the first trash bin he passed down the street. No, it’s a valuable book—valuable for what it has inside, I mean, though it’s a very costly set now. My niece looked it up on the Internet once, and her son told me what she’d learned—quite a few thousand—quite a few.”

“Maybe you should give the whole set to the library—the public library—or to the library at Witherspoon,” I suggested.

“Library—yes. I like that—Diane.”

“I can look up the phone numbers now and dial them for you, if you’d like.”

“I would. Yes. But first, let me give you two more things—besides that licorice tea and my other comments.”

I started to open my mouth, but he shook his head and said, “Be polite when your elders are speaking—Diane. If you do remember to confer with modern-day potters down south in Mexico, do me this favor. Confer with a cross section of four or five or six or ‘em. With everything, there’s a quality-control problem, and some know stuff another doesn’t, and vice versa. And you have no way of judging which one or two of ‘em is really first-rate—or what gaps each of ‘em might have—at least till you get to be a sharp-eyed judge of workmanship—which may or may not ever happen in your lifetime. That’s one. I thought of it while I was having my pee.”

He held up two fingers now.

“The other is to remember that education and schooling are usually two different things. Don’t confuse the two, especially where your own life is concerned. Don’t ever let your schooling get in the way of your real education—Diane.”

I stood and looked down at him, sitting on his tattered brown sofa, stroking his old cat. Then I took a blank Hospice Report form from my old canvas knapsack and began to write these bits of advice on the back of it. I told him what I was doing.

“You’ll remember them—Diane—without taking notes.”

“Yes, Patrick, but I want you to sign your name at the bottom of it when I’m done—I want to keep it as a treasure to remember you by. Can you see well enough to sign your name legibly for me?”

“I can do that. Then, when we’re done with that, you’ll help me find a new home for Mr. Ruskin’s works. Some place where people will really use them as books are meant to be used.”

I finished writing, and he looked it over with the aid of a large reading glass, nodded approvingly, and carefully signed it. Then, plopping Roscoe onto the floor, Patrick did his standup trick again.

“Nearest phone’s in the kitchen,” he said. “Know anyone who likes pussy cats? My niece is the kind of gal who’d think it a kindness to have him—put down—put to sleep, as they say—but I don’t think ol’ Ross is quite ready for that just yet.”

“Hmm,” I said. “Seems to me Roscoe doesn’t hate me too much. My landlord would have no objection, ‘cause other folks in my building have pets, and if my Hospice supervisor, Ms. Schwarz, approves it, we’ll do it on the up-and-up—as a ‘bequest,’ so to speak. And if she won’t, well, maybe I’ll just have to pay you a private-citizen type of visit some evening next week. I could give you a dollar for him, and once the sale is made, I could lend my great cat to you for the duration—if you like.”

Again Patrick Growel grinned broadly.

![]()