down in the dirt

welcome to volume 18 (February 2005) of

internet issn 1554-9623

(for the print issn 1554-9666)

Alexandira Rand, Editor

http://scars.tv - click on down in the dirt

down in the dirt

welcome to volume 18 (February 2005) of

internet issn 1554-9623

(for the print issn 1554-9666)

Alexandira Rand, Editor

http://scars.tv - click on down in the dirt

![]()

you are short but you don’t know it, there is always

a Bud Light in your hand, you are always talking among

friends, one hand in your pocket,

balled into a loose fist. I sit on the big red

couch by your side then follow

you around, vaguely, like a bleached-out shadow. I would like

your attention, or most of it. I couldn’t ask, please would you

validate my existence; that never goes over well, it sounds desperate.

I danced the other night, had to get drunk to do it. I didn’t care though.

I just puked into the toilet, four times, tasted Jager in my nostrils, then fell

backwards on my ass in the women’s bathroom in your

frat house and there was no one in there to help me up.

I know you don’t understand, I don’t have a home, there’s no water

pressure in my shower. That’s what makes me cry.

![]()

![]()

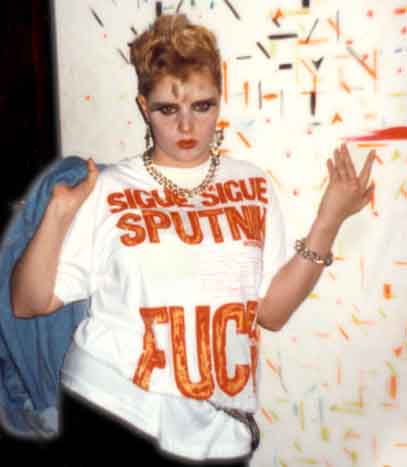

“Tampax” photos by Kyle Ramsay

|

Michelle Greenblatt

Far too long women have

Been bleeding and told to stop

Up our wounds with Tampax

![]()

![]()

![]() As if her sudden death wasn’t enough, there is more. Now I find myself attracted to a man. And I am sick of listening to Reverend Talbot telling me about God’s plan. Would he say it was God’s plan if I told him about Michael? For me, this supposed plan, this answer for all unanswerable questions, is phoney. It does not bring solace. It is a worthless cliche so often spewed from the mouth of a white suited TV evangelist, the one recently arrested with a prostitute.

As if her sudden death wasn’t enough, there is more. Now I find myself attracted to a man. And I am sick of listening to Reverend Talbot telling me about God’s plan. Would he say it was God’s plan if I told him about Michael? For me, this supposed plan, this answer for all unanswerable questions, is phoney. It does not bring solace. It is a worthless cliche so often spewed from the mouth of a white suited TV evangelist, the one recently arrested with a prostitute.

![]() During the five months she has been gone I have been invited to dinner in the homes of several kind old ladies on the Caring Committee from church. Small talk is difficult when I want to scream about what is fair. None of the couples we know have invited me. Evidently I don’t fit in any more. At church I listen to their stumbling words and want to respond with sarcastic laughter.

During the five months she has been gone I have been invited to dinner in the homes of several kind old ladies on the Caring Committee from church. Small talk is difficult when I want to scream about what is fair. None of the couples we know have invited me. Evidently I don’t fit in any more. At church I listen to their stumbling words and want to respond with sarcastic laughter.

![]() Our son and daughter call every week to see how I’m doing and I cover well. We had another son but he died suddenly three years ago. That was supposed to be God’s plan too. Reverend Talbot said so.

Our son and daughter call every week to see how I’m doing and I cover well. We had another son but he died suddenly three years ago. That was supposed to be God’s plan too. Reverend Talbot said so.

![]() I had expected to have difficulty, but not with this other dimension. Often I spend the night walking through our empty house, unable to sleep, asking the un-answerable why. I sit down and try to read but don’t see the words, then go back to bed until it is light.

I had expected to have difficulty, but not with this other dimension. Often I spend the night walking through our empty house, unable to sleep, asking the un-answerable why. I sit down and try to read but don’t see the words, then go back to bed until it is light.

![]() Michael is one of the company representatives I talk to on the phone. We’ve had several business lunches together, but always with management people from the company he works for. Sometimes he has walked to my car with me. We’ve never seen each other socially or talked about personal things.

Michael is one of the company representatives I talk to on the phone. We’ve had several business lunches together, but always with management people from the company he works for. Sometimes he has walked to my car with me. We’ve never seen each other socially or talked about personal things.

![]() But he knows.

But he knows.

![]() He has called twice since she has been gone, to our home phone rather than the business line.

He has called twice since she has been gone, to our home phone rather than the business line.

![]() It is morning. It takes great effort even to get dressed. I find the empty bourbon bottle under the bed and throw it into the trash. My hands shake so much I drop the coffee carafe then kick its broken pieces across the kitchen floor. Finally I sit down in despair thinking about my gun in the kitchen drawer. The telephone rings.

It is morning. It takes great effort even to get dressed. I find the empty bourbon bottle under the bed and throw it into the trash. My hands shake so much I drop the coffee carafe then kick its broken pieces across the kitchen floor. Finally I sit down in despair thinking about my gun in the kitchen drawer. The telephone rings.

![]() “This is Michael. I want you to come to the beach this weekend. I think it will be good for you.”

“This is Michael. I want you to come to the beach this weekend. I think it will be good for you.”

![]() Goose pimples rise on my arms. “I’d like that,” I say. It is a defiant choice, not compulsion.

Goose pimples rise on my arms. “I’d like that,” I say. It is a defiant choice, not compulsion.

![]() Michael lives two hours away. When we meet he suggests we continue on to the beach in his car. Riding in it gives me a lift but it is noisy with the top down.

Michael lives two hours away. When we meet he suggests we continue on to the beach in his car. Riding in it gives me a lift but it is noisy with the top down.

![]() We change into our bathing suits at the motel. My fantasy had him in a small bikini but he wears cutoffs. We walk on the beach and I feel the accumulated tensions leaving my body. A single, pleasant one takes their place. When we hold hands I imagine others watching.

We change into our bathing suits at the motel. My fantasy had him in a small bikini but he wears cutoffs. We walk on the beach and I feel the accumulated tensions leaving my body. A single, pleasant one takes their place. When we hold hands I imagine others watching.

![]() We go into the water for a short time then back to the room and take a shower together. We soap each other. Michael likes it. I do not. I wonder if it is because everything about me is tangled and distorted.

We go into the water for a short time then back to the room and take a shower together. We soap each other. Michael likes it. I do not. I wonder if it is because everything about me is tangled and distorted.

![]() We go to a restaurant Michael knows. I have been to Oceanside many times but never noticed it. Candles are the only lighting. All of the couples are men. Conversation is subdued and a pianist plays softly. The food is excellent, the waiters attentive. I wonder if they think I am Michael’s father, then realize men probably don’t come to places like this with their fathers.

We go to a restaurant Michael knows. I have been to Oceanside many times but never noticed it. Candles are the only lighting. All of the couples are men. Conversation is subdued and a pianist plays softly. The food is excellent, the waiters attentive. I wonder if they think I am Michael’s father, then realize men probably don’t come to places like this with their fathers.

![]() Back at the room we hang up our clothes without speaking. Still silent, we stand for a moment looking at each other before getting into bed. For me, fantasy and reality look at each other across a chasm of guilt, anger and ten thousand must nots.

Back at the room we hang up our clothes without speaking. Still silent, we stand for a moment looking at each other before getting into bed. For me, fantasy and reality look at each other across a chasm of guilt, anger and ten thousand must nots.

![]() I am afraid but he is gentle, almost delicate. Then he tells me what he needs. Afterward I turn off the lamp. He lies against my chest, his head under my chin. The hoped for relaxation does not appear. Only guilt.

I am afraid but he is gentle, almost delicate. Then he tells me what he needs. Afterward I turn off the lamp. He lies against my chest, his head under my chin. The hoped for relaxation does not appear. Only guilt.

![]() “This is new for me,” I say.

“This is new for me,” I say.

![]() “Not even on camp outs when you were thirteen?”

“Not even on camp outs when you were thirteen?”

![]() “No, I was the last to mature. Being teased about something over which I had no control left me feeling inferior and afraid. Some of that has carried over into my adult life.”

“No, I was the last to mature. Being teased about something over which I had no control left me feeling inferior and afraid. Some of that has carried over into my adult life.”

![]() “Yes,” Michael says,”maybe that’s why you’re always jumping up to do things for others, as if you need their approval. That’s how you are at our business lunches with the big guns. I’ve wanted to tell you to relax.”

“Yes,” Michael says,”maybe that’s why you’re always jumping up to do things for others, as if you need their approval. That’s how you are at our business lunches with the big guns. I’ve wanted to tell you to relax.”

![]() There is no need to respond. He is right.

There is no need to respond. He is right.

![]() “With all the interesting things you’ve done in your life and all the places you’ve lived,” I ask, “why are you in that terrible job?”

“With all the interesting things you’ve done in your life and all the places you’ve lived,” I ask, “why are you in that terrible job?”

![]() “Because it is something not many can do. Knowing that gives me a feeling of self respect.”

“Because it is something not many can do. Knowing that gives me a feeling of self respect.”

![]() “The training you’ve had is way above that,” I say.

“The training you’ve had is way above that,” I say.

![]() His hand rubs my face. “You look beyond the prejudice that keeps others from hiring me,” he says. “Don’t you do things because you need to feel self respect?”

His hand rubs my face. “You look beyond the prejudice that keeps others from hiring me,” he says. “Don’t you do things because you need to feel self respect?”

![]() I think of the worthless college degrees I have collected but don’t answer, changing the subject instead. “I’m pleased but surprised you would call. I’m thinking about our age difference.”

I think of the worthless college degrees I have collected but don’t answer, changing the subject instead. “I’m pleased but surprised you would call. I’m thinking about our age difference.”

![]() His smile reassures. “Age has nothing to do with it,” he says.

His smile reassures. “Age has nothing to do with it,” he says.

![]() He sleeps well. I don’t, afraid I have made a horrible mistake. I look at Michael. The guilt always waiting in the wings again comes to center stage, its weight crushing any good feeling there might be.

He sleeps well. I don’t, afraid I have made a horrible mistake. I look at Michael. The guilt always waiting in the wings again comes to center stage, its weight crushing any good feeling there might be.

![]() I get up early, put on my pajamas, and read the paper. Our motel room is new and I wonder who did the finish work. The pocket door to the bathroom is an inch short. The plastic base board material is loose. A curtain rod is low on one end. Everything not quite right. I identify with that.

I get up early, put on my pajamas, and read the paper. Our motel room is new and I wonder who did the finish work. The pocket door to the bathroom is an inch short. The plastic base board material is loose. A curtain rod is low on one end. Everything not quite right. I identify with that.

![]() Michael wakes up. I make him a cup of coffee and sit on the edge of the bed.

Michael wakes up. I make him a cup of coffee and sit on the edge of the bed.

![]() He touches my back. “This was new for you but I have always been this way,” he says. “It is lonely and I am not one to indiscriminately reach out.” His voice is soft. “I’m attracted to you because you allow yourself to be open, to show your feelings.”

He touches my back. “This was new for you but I have always been this way,” he says. “It is lonely and I am not one to indiscriminately reach out.” His voice is soft. “I’m attracted to you because you allow yourself to be open, to show your feelings.”

![]() Far too sensitive, I say to myself. Too open to hurt and guilt. Vulnerable. Feminine. We talk for hours. He asks a lot of caring questions about her. I cannot think of a way to tell him what I have to. At noon we have champagne cocktails at an outdoor restaurant, then lunch.

Far too sensitive, I say to myself. Too open to hurt and guilt. Vulnerable. Feminine. We talk for hours. He asks a lot of caring questions about her. I cannot think of a way to tell him what I have to. At noon we have champagne cocktails at an outdoor restaurant, then lunch.

![]() We go to the beach then to a little shopping mall where Michael buys me a container of violet starts for my garden. In the early afternoon we take showers separately and get ready to leave. We embrace before we dress but men’s bodies don’t fit together like those of man and woman.

We go to the beach then to a little shopping mall where Michael buys me a container of violet starts for my garden. In the early afternoon we take showers separately and get ready to leave. We embrace before we dress but men’s bodies don’t fit together like those of man and woman.

![]() The noisy convertible makes conversation difficult, giving me time to decide what to say.

The noisy convertible makes conversation difficult, giving me time to decide what to say.

![]() He stops next to my car and speaks before I can.

He stops next to my car and speaks before I can.

![]() “This isn’t right for you,” he says, “I can tell.”

“This isn’t right for you,” he says, “I can tell.”

![]() “Michael, I don’t know and I’m afraid.”

“Michael, I don’t know and I’m afraid.”

![]() He rubs the back of my neck. “Its OK,” he turns his face away, “you aren’t the only one who is afraid. I’ve never found anyone who I really wanted to be with,” he swallows. “Until...”

He rubs the back of my neck. “Its OK,” he turns his face away, “you aren’t the only one who is afraid. I’ve never found anyone who I really wanted to be with,” he swallows. “Until...”

![]() He turns to me and I see the tears in his eyes. It rips my guts out.

He turns to me and I see the tears in his eyes. It rips my guts out.

![]() I try to find things to do at home. The next morning I go to the China cabinet and take out the good China I never liked, have it packed and sent to our daughter. I buy a simple blue and white set to replace it. After planting the violet starts Michael gave me I pull out all the dwarf Barberry bushes that line the front walk and replace them with Dusty Miller.

I try to find things to do at home. The next morning I go to the China cabinet and take out the good China I never liked, have it packed and sent to our daughter. I buy a simple blue and white set to replace it. After planting the violet starts Michael gave me I pull out all the dwarf Barberry bushes that line the front walk and replace them with Dusty Miller.

![]() Goodwill comes to pick up the heavy coffee table I don’t want any more. I start to empty its single drawer, then stop. Her reading glasses are there. The auger in my stomach makes another turn and I dread finding other things of hers.

Goodwill comes to pick up the heavy coffee table I don’t want any more. I start to empty its single drawer, then stop. Her reading glasses are there. The auger in my stomach makes another turn and I dread finding other things of hers.

![]() I invite two couples for lunch after church. I always did most of the cooking. It was a secret she and I had. They like the chicken salad. It is the one with red grapes and toasted almonds with the chicken marinated in raspberry vinegar. I make cheese sticks and the wine is a dry semillon.

I invite two couples for lunch after church. I always did most of the cooking. It was a secret she and I had. They like the chicken salad. It is the one with red grapes and toasted almonds with the chicken marinated in raspberry vinegar. I make cheese sticks and the wine is a dry semillon.

![]() Later, when I am putting dishes into the dish washer, Maxine Johnson comes into the kitchen. We have known Maxine and Bill for a long time.

Later, when I am putting dishes into the dish washer, Maxine Johnson comes into the kitchen. We have known Maxine and Bill for a long time.

![]() “The salad was excellent, Frank. All these years and we didn’t know you cooked.” She stands too close. “Bill is gone all next week helping his brother.” Her tone of voice says more. “Come over some evening. Late when its dark. We’ll go into the hot tub. It’ll be good for you.”

“The salad was excellent, Frank. All these years and we didn’t know you cooked.” She stands too close. “Bill is gone all next week helping his brother.” Her tone of voice says more. “Come over some evening. Late when its dark. We’ll go into the hot tub. It’ll be good for you.”

![]() She has never been like this before. Perhaps it is something she too, has wanted to try.

She has never been like this before. Perhaps it is something she too, has wanted to try.

![]() “I’d like to come over when both you and Bill are there,” I say.

“I’d like to come over when both you and Bill are there,” I say.

![]() She blushes. Bill comes into the kitchen. “There you are,” he says, looking at both of us. He takes her arm. “C’mon,” he says. His look tells me he thinks I was hitting on her. I know I am crossed off their list.

She blushes. Bill comes into the kitchen. “There you are,” he says, looking at both of us. He takes her arm. “C’mon,” he says. His look tells me he thinks I was hitting on her. I know I am crossed off their list.

![]() Next I invite the Rawsons. Recently retired, they have just moved here so there is no history on either side. I had spoken to them the first time they were in church.

Next I invite the Rawsons. Recently retired, they have just moved here so there is no history on either side. I had spoken to them the first time they were in church.

![]() Don Rawson calls a couple of days before the dinner. “Frank, my sister is visiting us unexpectedly. OK if we bring her? She recently lost her hubby.”

Don Rawson calls a couple of days before the dinner. “Frank, my sister is visiting us unexpectedly. OK if we bring her? She recently lost her hubby.”

![]() I prepare the pot roast in beer. Potatoes, carrots and onion go in when the roast is almost ready. I had made a relish plate and the green salad before going to church. The last of the Key lime juice she and I got in the Caribbean went into the pie I made last night. A Gamay goes well with the roast.

I prepare the pot roast in beer. Potatoes, carrots and onion go in when the roast is almost ready. I had made a relish plate and the green salad before going to church. The last of the Key lime juice she and I got in the Caribbean went into the pie I made last night. A Gamay goes well with the roast.

![]() Benita Rawson and Don’s sister come into the kitchen after we have eaten. His sister is tall, over weight and wearing a heavy perfume that partially covers her perspiration odor.

Benita Rawson and Don’s sister come into the kitchen after we have eaten. His sister is tall, over weight and wearing a heavy perfume that partially covers her perspiration odor.

![]() “Our turn,” Benita laughs, taking my arm and guiding me out of the kitchen. “The chef cooks but the slaves clean up. We’ve been watching. You’re the quintessential care giver. Time to receive.”

“Our turn,” Benita laughs, taking my arm and guiding me out of the kitchen. “The chef cooks but the slaves clean up. We’ve been watching. You’re the quintessential care giver. Time to receive.”

![]() “How about going fishing with us down the river for a few days?” Don says when they are leaving. “It would be just the four of us.” His sister watches, smiling.

“How about going fishing with us down the river for a few days?” Don says when they are leaving. “It would be just the four of us.” His sister watches, smiling.

![]() “I’ll call you,” I say.

“I’ll call you,” I say.

![]() They leave. I go to the office and check the answering machine for messages.

They leave. I go to the office and check the answering machine for messages.

![]() Michael has called.

Michael has called.

![]() With effort I turn away from the phone, wanting to return Michael’s call and at the same time not wanting to. I drink the rest of the wine, then start on a bottle of bourbon. I look at the drawer with the gun in it.

With effort I turn away from the phone, wanting to return Michael’s call and at the same time not wanting to. I drink the rest of the wine, then start on a bottle of bourbon. I look at the drawer with the gun in it.

![]() On the last day of the fishing trip Don and Benita go hiking at dusk. His sister and I go into the water. When we come out she unzips her bathing suit and looks at me, smiling. It is her third invitation in as many days. I should have gone hiking with Don and Benita. I mumble something about going to look for a good fishing spot. Later she comes to my tent. I tell her to go away.

On the last day of the fishing trip Don and Benita go hiking at dusk. His sister and I go into the water. When we come out she unzips her bathing suit and looks at me, smiling. It is her third invitation in as many days. I should have gone hiking with Don and Benita. I mumble something about going to look for a good fishing spot. Later she comes to my tent. I tell her to go away.

![]() The next afternoon they drop me off in front of the house. I do not invite them in. I rush to the liquor cupboard, take a bottle out and mix a drink. Then another. Several. Oblivion beckons. I go to the drawer and take the gun out. I set it on the counter. I hesitate, then drink directly from the bottle. Vomit runs down the front of my shirt. I look at the gun. I pick it up. The barrel is cold in my mouth. My hand shakes. Then something inside me cries out. I put the gun down and stay up the rest of the night.

The next afternoon they drop me off in front of the house. I do not invite them in. I rush to the liquor cupboard, take a bottle out and mix a drink. Then another. Several. Oblivion beckons. I go to the drawer and take the gun out. I set it on the counter. I hesitate, then drink directly from the bottle. Vomit runs down the front of my shirt. I look at the gun. I pick it up. The barrel is cold in my mouth. My hand shakes. Then something inside me cries out. I put the gun down and stay up the rest of the night.

![]() “I miss her so much, yet I went to the beach with Michael,” I say to the psychologist.

“I miss her so much, yet I went to the beach with Michael,” I say to the psychologist.

![]() “So you’re going to flog yourself forever because you had sex with a man?” he says. “You say what you did isn’t right for you. Or does it just go against what others know and think about you?”

“So you’re going to flog yourself forever because you had sex with a man?” he says. “You say what you did isn’t right for you. Or does it just go against what others know and think about you?”

![]() I can’t answer. I don’t know.

I can’t answer. I don’t know.

![]() He waits, then continues. “Will you tell me more about your relationship with Michael?”

He waits, then continues. “Will you tell me more about your relationship with Michael?”

![]() “I was stupid.”

“I was stupid.”

![]() He holds up his hand. “I asked you a question.”

He holds up his hand. “I asked you a question.”

![]() “We had a good time together and have lots in common, but I guess sex was not, it didn’t seem right for me.”

“We had a good time together and have lots in common, but I guess sex was not, it didn’t seem right for me.”

![]() “Sex with a man isn’t your thing and you’ve said another woman could never measure up to what you had. Do you see what you’ve done to yourself?” he asks.

“Sex with a man isn’t your thing and you’ve said another woman could never measure up to what you had. Do you see what you’ve done to yourself?” he asks.

![]() “Yes, I’ve turned everything into shit!” I spit out the words.

“Yes, I’ve turned everything into shit!” I spit out the words.

![]() “Listen! If you want to feel sorry for yourself you don’t need me to talk to. The world is full of practicing experts in that area. I asked you a question.”

“Listen! If you want to feel sorry for yourself you don’t need me to talk to. The world is full of practicing experts in that area. I asked you a question.”

![]() “I have put myself into an impossible position,” I say.

“I have put myself into an impossible position,” I say.

![]() “Now we’re getting somewhere. Tell me more about your wife.”

“Now we’re getting somewhere. Tell me more about your wife.”

![]() It takes a long time.

It takes a long time.

![]() “I’ve got the picture,” he says. “You can work yourself out of this or go the self pity route. Which is it?”

“I’ve got the picture,” he says. “You can work yourself out of this or go the self pity route. Which is it?”

![]() I start to speak. He holds up his hand again.

I start to speak. He holds up his hand again.

![]() “It would also be a good idea to explore your having to do so much for others. Even with sex. How did you feel when Michael did things for you? Or when your wife did?”

“It would also be a good idea to explore your having to do so much for others. Even with sex. How did you feel when Michael did things for you? Or when your wife did?”

![]() “With her, I had to be so noble. I always had to be the one to do everything. With Michael I’m...I don’t know.”

“With her, I had to be so noble. I always had to be the one to do everything. With Michael I’m...I don’t know.”

![]() “I don’t know. I don’t know. In always doing for others are you blind to people wanting to do things for you?

“I don’t know. I don’t know. In always doing for others are you blind to people wanting to do things for you?

![]() “No!”

“No!”

![]() “Or do you feed others only so you can get what you need from them?”

“Or do you feed others only so you can get what you need from them?”

![]() “Wait just one damn minute!”

“Wait just one damn minute!”

![]() He leans forward. “Ah! Talk about your anger.”

He leans forward. “Ah! Talk about your anger.”

![]() I have a lot to say.

I have a lot to say.

![]() He pushes the box of tissues toward me. “So there’s anger mixed with the fear. I’ve heard some classic examples of wrong thinking too.” He stops. “You OK? What are you feeling right now?”

He pushes the box of tissues toward me. “So there’s anger mixed with the fear. I’ve heard some classic examples of wrong thinking too.” He stops. “You OK? What are you feeling right now?”

![]() “Stupid but relieved now there is someone I can talk to.”

“Stupid but relieved now there is someone I can talk to.”

![]() “This is a start. I can help but you have to find the answers for yourself and you can’t reason if you are depressed. I’ll call your medical group and get a prescription. Make sure you pick it up today. I’m guessing your booze consumption has gone way up too. With the meds you’ll be taking that has to stop.”

“This is a start. I can help but you have to find the answers for yourself and you can’t reason if you are depressed. I’ll call your medical group and get a prescription. Make sure you pick it up today. I’m guessing your booze consumption has gone way up too. With the meds you’ll be taking that has to stop.”

![]() He leans forward again. “One last thing. I need a commitment that you will call me rather than kill yourself.”

He leans forward again. “One last thing. I need a commitment that you will call me rather than kill yourself.”

![]() “I can give you that.”

“I can give you that.”

![]() “Then you’ve decided to live?”

“Then you’ve decided to live?”

![]() “Yes.”

“Yes.”

![]() “OK,” he sits back,”bring me the gun.”

“OK,” he sits back,”bring me the gun.”

![]() In the last three months Michael and I have had no contact. The confusion remains and I keep telling myself I’m handling it OK. Then late one night the phone rings. It is Michael. I am afraid.

In the last three months Michael and I have had no contact. The confusion remains and I keep telling myself I’m handling it OK. Then late one night the phone rings. It is Michael. I am afraid.

![]() “How have things been going for you?” he asks.

“How have things been going for you?” he asks.

![]() “You already know.”

“You already know.”

![]() “Don’t be so hard on yourself,” he says.

“Don’t be so hard on yourself,” he says.

![]() “Always that,” I respond.

“Always that,” I respond.

![]() “I hope things will get better for you,” he says.

“I hope things will get better for you,” he says.

![]() “The violets are growing,” I say, wanting to tell him I’m lonely.

“The violets are growing,” I say, wanting to tell him I’m lonely.

![]() “I’m living in Vermont,” he says.

“I’m living in Vermont,” he says.

![]() An instant sadness comes over me. “I had something to do with that. I’m sorry.”

An instant sadness comes over me. “I had something to do with that. I’m sorry.”

![]() “I knew that’s what you would say,” he responds. “Don’t be sorry. I move a lot.”

“I knew that’s what you would say,” he responds. “Don’t be sorry. I move a lot.”

![]() There is a long pause. I wait for him to speak. “I’m calling on the chance you might come here and be with me.”

There is a long pause. I wait for him to speak. “I’m calling on the chance you might come here and be with me.”

![]() I close my eyes and take several quick, shallow breaths. In that instant my confusion disappears.

I close my eyes and take several quick, shallow breaths. In that instant my confusion disappears.

![]() “Yes, Michael, yes. Give me your phone number.

“Yes, Michael, yes. Give me your phone number.

![]() “I was so afraid...I didn’t think that...I’m so glad.”

“I was so afraid...I didn’t think that...I’m so glad.”

![]() He gives me his phone number and address. “Hurry,” he says.

He gives me his phone number and address. “Hurry,” he says.

![]() “There are some things I’ve got to take care of here.”

“There are some things I’ve got to take care of here.”

![]() “Hurry,” he says again.

“Hurry,” he says again.

![]() I go to the kitchen window and watch the full moon come up.

I go to the kitchen window and watch the full moon come up.

![]() For the first time in many months, I am sleepy.

For the first time in many months, I am sleepy.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() I had just finished studying for my Comparative Literature mid-term and was dashing off a letter to my dear parents in the UK and enjoying some chamomile tea when Bones exploded into the room, bringing with him a sudden gust of wind that carried the odor of stale tobacco and cheap ale. With Bones, so named for his fondness for playing dominoes, it was not an entirely unusual circumstance for him to stumble back to the dormitory late at night, inebriated and wild of tongue. But this was different. His face was slate gray, and his eyes so wide I thought they might pop out at any moment and roll under the bunk. I was already halfway out of my chair when he collapsed into my arms and started gibbering unintelligably. I hauled him to the bunk and tried to lay him down, but he clung to me like a man dangling from the precipice of a bottomless canyon.

I had just finished studying for my Comparative Literature mid-term and was dashing off a letter to my dear parents in the UK and enjoying some chamomile tea when Bones exploded into the room, bringing with him a sudden gust of wind that carried the odor of stale tobacco and cheap ale. With Bones, so named for his fondness for playing dominoes, it was not an entirely unusual circumstance for him to stumble back to the dormitory late at night, inebriated and wild of tongue. But this was different. His face was slate gray, and his eyes so wide I thought they might pop out at any moment and roll under the bunk. I was already halfway out of my chair when he collapsed into my arms and started gibbering unintelligably. I hauled him to the bunk and tried to lay him down, but he clung to me like a man dangling from the precipice of a bottomless canyon.

![]() When I finally managed to wrest myself from Bones’ steely grip, my first instinct was to retrieve a cold compress for his head. Instead, I grabbed a bottle of corvousier from the bookshelf, poured a capful and brought it to his quivering lips. The poor boy’s whole body spasmed as he choked it down, and a deep flush bloomed in his cheeks. His eyes, those terrible eyes, squinted gratefully shut for a moment, then reopened and resumed their wild search.

When I finally managed to wrest myself from Bones’ steely grip, my first instinct was to retrieve a cold compress for his head. Instead, I grabbed a bottle of corvousier from the bookshelf, poured a capful and brought it to his quivering lips. The poor boy’s whole body spasmed as he choked it down, and a deep flush bloomed in his cheeks. His eyes, those terrible eyes, squinted gratefully shut for a moment, then reopened and resumed their wild search.

![]() “Easy now, Bones, easy,” I said, cradling his head. I was afraid that if he didn’t calm down soon, I might have to phone the ambulance. My First Aid training as a lifeguard in Sothesby two summers ago would only take me so far here before his well-being might run completely out of my hands. “Tell me the matter, man. What perturbs you so?”

“Easy now, Bones, easy,” I said, cradling his head. I was afraid that if he didn’t calm down soon, I might have to phone the ambulance. My First Aid training as a lifeguard in Sothesby two summers ago would only take me so far here before his well-being might run completely out of my hands. “Tell me the matter, man. What perturbs you so?”

![]() Just then, a breeze rattled the window and blew the letter I’d been writing off my desk. Bones snapped his head toward the sound, leaped off the bed and scrambled madly toward the door. Despite being caught off-guard by his sudden movement, I managed to hook an arm around his legs and trip him. His chin smacked the floor with a sound like billiard balls clacking together, and I felt his body go limp as he fell unconscious.

Just then, a breeze rattled the window and blew the letter I’d been writing off my desk. Bones snapped his head toward the sound, leaped off the bed and scrambled madly toward the door. Despite being caught off-guard by his sudden movement, I managed to hook an arm around his legs and trip him. His chin smacked the floor with a sound like billiard balls clacking together, and I felt his body go limp as he fell unconscious.

![]() I sprang to my feet and rolled him over, cursing myself for having tackled him so violently. Now that he was nearly comatose, I couldn’t query him further on the source of his terror-stricken demeanor. I patted him down, searching for anything that might give me a clue as to his whereabouts earlier in the evening, and came across a damp spot on his leg. When my fingertips came back red, I hastily grabbed my Bowie knife from the bureau and slashed apart his denim trousers. I felt my jaw unhinge and fell backward onto my buttocks at the sight before me: a six-inch gash running from Bones’ ankle to his calf. My blood ran cold at the thought of who or what was responsible for this abhorrent assault. Given Bones’ distress, this cut was not the result of a drunkenly prance through rose bushes or even the loss of equilibrium on his sojourn home from the tavern. This dastardly deed must have been perpetrated by a malicious hooligan or strung-out opium addict.

I sprang to my feet and rolled him over, cursing myself for having tackled him so violently. Now that he was nearly comatose, I couldn’t query him further on the source of his terror-stricken demeanor. I patted him down, searching for anything that might give me a clue as to his whereabouts earlier in the evening, and came across a damp spot on his leg. When my fingertips came back red, I hastily grabbed my Bowie knife from the bureau and slashed apart his denim trousers. I felt my jaw unhinge and fell backward onto my buttocks at the sight before me: a six-inch gash running from Bones’ ankle to his calf. My blood ran cold at the thought of who or what was responsible for this abhorrent assault. Given Bones’ distress, this cut was not the result of a drunkenly prance through rose bushes or even the loss of equilibrium on his sojourn home from the tavern. This dastardly deed must have been perpetrated by a malicious hooligan or strung-out opium addict.

![]() Fury must have gotten the better of me at that moment because I leapt to my feet, tore open the closet, and retrieved a slender pine box from the top shelf. Inside it was the Remington rifle my father had bestowed upon me with the understanding that I would use it only when absolutely necessary. Now was one of those times. The campus was largely deserted for spring break, so there were no colleagues to call upon for help in this matter. The campus security personnel were utterly inept; those good-for-nothing fools were probably tipped back by the telly, snoring away among empty Krispy Kreme boxes and tattered pornographic magazines. And since ours was a rural college, the fastest the local constable could motor here was 40 minutes, and by that time the perpetrator would probably be long gone. No, the time to act was now, and alone with only my wits and a keen sense of loyalty to my criminalized friend.

Fury must have gotten the better of me at that moment because I leapt to my feet, tore open the closet, and retrieved a slender pine box from the top shelf. Inside it was the Remington rifle my father had bestowed upon me with the understanding that I would use it only when absolutely necessary. Now was one of those times. The campus was largely deserted for spring break, so there were no colleagues to call upon for help in this matter. The campus security personnel were utterly inept; those good-for-nothing fools were probably tipped back by the telly, snoring away among empty Krispy Kreme boxes and tattered pornographic magazines. And since ours was a rural college, the fastest the local constable could motor here was 40 minutes, and by that time the perpetrator would probably be long gone. No, the time to act was now, and alone with only my wits and a keen sense of loyalty to my criminalized friend.

![]() I loaded the Remington and slipped on my peacoat to guard against the March chill outside. Slipping into the hallway, I was immediately unnerved by the quiet. Usually, a leisurely stroll through this corridor could expose one to a myriad of different sounds: the high-pitched moaning of a couple engaged in coitus, the blaring wail of an electric guitar from a Jimi Hendrix or Led Zeppelin tune, farting and belching from a contest between a gaggle of neanderthalithic pledges hoping to join their favorite fraternity. But the sources of these noises were elsewhere this week, probably in Cancun or South Padre Island or St. Maarten where they would undoubtedly be imbibing cheap ale and grinding body parts with complete strangers in packed nightclubs. Bones had chosen to stay on campus because he lacked the funds to travel to such exotic locales, and, if you believed him, so that he would have his favorite local watering holes to himself. My parents were on a skiing vacation in the Swiss Alps, so the only welcoming sound I would have heard at home was the chime of our grandfather clock or the mew of our cherished cat Gypsy. It was only Bones and I, at least in this section of campus, and that reality was now more than a little unsettling.

I loaded the Remington and slipped on my peacoat to guard against the March chill outside. Slipping into the hallway, I was immediately unnerved by the quiet. Usually, a leisurely stroll through this corridor could expose one to a myriad of different sounds: the high-pitched moaning of a couple engaged in coitus, the blaring wail of an electric guitar from a Jimi Hendrix or Led Zeppelin tune, farting and belching from a contest between a gaggle of neanderthalithic pledges hoping to join their favorite fraternity. But the sources of these noises were elsewhere this week, probably in Cancun or South Padre Island or St. Maarten where they would undoubtedly be imbibing cheap ale and grinding body parts with complete strangers in packed nightclubs. Bones had chosen to stay on campus because he lacked the funds to travel to such exotic locales, and, if you believed him, so that he would have his favorite local watering holes to himself. My parents were on a skiing vacation in the Swiss Alps, so the only welcoming sound I would have heard at home was the chime of our grandfather clock or the mew of our cherished cat Gypsy. It was only Bones and I, at least in this section of campus, and that reality was now more than a little unsettling.

![]() As I came upon the stairwell, I stopped abruptly and reflected upon the situation. Perhaps I should call the campus authorities. For all their incompetence, they at the very least would turn the odds in our favor three to one if there was indeed a single perpetrator. But I discarded the thought, ashamed at my own cowardice. This was my first opportunity to extract myself from academia, to shrug off my cloak of intellect and philosophical endeavor in favor of utilizing more primal instincts, defense tactics and survival strategies. Would I embrace the challenge, slay the beast and avenge my dear friend or run back to the shelter of a textbook?

As I came upon the stairwell, I stopped abruptly and reflected upon the situation. Perhaps I should call the campus authorities. For all their incompetence, they at the very least would turn the odds in our favor three to one if there was indeed a single perpetrator. But I discarded the thought, ashamed at my own cowardice. This was my first opportunity to extract myself from academia, to shrug off my cloak of intellect and philosophical endeavor in favor of utilizing more primal instincts, defense tactics and survival strategies. Would I embrace the challenge, slay the beast and avenge my dear friend or run back to the shelter of a textbook?

![]() My thoughts were interrupted by the sight of blood droplets, crimson dimes scattered on the slate gray stairs that I assumed had come from Bones. They served to reinstill my sense of urgency, and my grip on the Remington grew ever tighter as a leaped down the stairs by threes, grimacing as I sidestepped the grisly spatters Bones had left behind. Perhaps I had gotten too excited, for I stumbled with three steps to go and lost my balance. I could see a likely scenario unfolding before me as I fell: I would crack my head on the concrete floor and lose consciousness. The gun would discharge, alarming the rent-a-cops. They would find me as I lie, with a warm gun, blood droplets on the stairs, and Bones injured in my room. Soon I would be shackled and dragged off to the hoosegow for attempted murder, with Bones, in his stupefied state, unable to confirm what had happened to him.

My thoughts were interrupted by the sight of blood droplets, crimson dimes scattered on the slate gray stairs that I assumed had come from Bones. They served to reinstill my sense of urgency, and my grip on the Remington grew ever tighter as a leaped down the stairs by threes, grimacing as I sidestepped the grisly spatters Bones had left behind. Perhaps I had gotten too excited, for I stumbled with three steps to go and lost my balance. I could see a likely scenario unfolding before me as I fell: I would crack my head on the concrete floor and lose consciousness. The gun would discharge, alarming the rent-a-cops. They would find me as I lie, with a warm gun, blood droplets on the stairs, and Bones injured in my room. Soon I would be shackled and dragged off to the hoosegow for attempted murder, with Bones, in his stupefied state, unable to confirm what had happened to him.

![]() But the gun didn’t discharge. It click-clacked to the corner where I tossed it out of harm’s way and I crashed through the exit door into the cool night. As I lie on the ground, the wind knocked out of me, nursing a sore shoulder, I was immediately taken by how quiet it was outside. There was no traffic on the road, and only a whisper of wind stirred the skeletal trees into symphony. Far off, a dog barked.

But the gun didn’t discharge. It click-clacked to the corner where I tossed it out of harm’s way and I crashed through the exit door into the cool night. As I lie on the ground, the wind knocked out of me, nursing a sore shoulder, I was immediately taken by how quiet it was outside. There was no traffic on the road, and only a whisper of wind stirred the skeletal trees into symphony. Far off, a dog barked.

![]() I got up gingerly, holding my breath for fear of making the slightest noise. I no longer had the protection of being inside the building, and the realization of that made me rest my finger close to the Remington’s trigger. I scanned the moonlit courtyard but sighted nothing suspicious, only a dog poking around in the withered and colorless garden. The sight of him comforted me greatly. I whistled low to him, not wanting to alert a hiding assailant to my presence. He showed no reaction whatsoever, continuing to forage around for Lord knows what. I slapped my leg next and made a smooching sound with my lips, and for the first time he stopped his manic search.

I got up gingerly, holding my breath for fear of making the slightest noise. I no longer had the protection of being inside the building, and the realization of that made me rest my finger close to the Remington’s trigger. I scanned the moonlit courtyard but sighted nothing suspicious, only a dog poking around in the withered and colorless garden. The sight of him comforted me greatly. I whistled low to him, not wanting to alert a hiding assailant to my presence. He showed no reaction whatsoever, continuing to forage around for Lord knows what. I slapped my leg next and made a smooching sound with my lips, and for the first time he stopped his manic search.

![]() All at once, I wish I hadn’t gotten the beast’s attention. He emitted a low growl and, for the first time, turned to face me. His face was obscured in shadow, but I imagined coal black eyes and silver teeth glistening with saliva.

All at once, I wish I hadn’t gotten the beast’s attention. He emitted a low growl and, for the first time, turned to face me. His face was obscured in shadow, but I imagined coal black eyes and silver teeth glistening with saliva.

![]() I took a step back toward the door. Then, I witnessed something that violated everything I knew, all of my university training, the rules of science and evolution. The dog began to stand up. He did it slowly, but my eyes weren’t deceiving me. My rationality was shattered more quickly than I ever thought as I stared at a creature that I had previously believed to be mythical.

I took a step back toward the door. Then, I witnessed something that violated everything I knew, all of my university training, the rules of science and evolution. The dog began to stand up. He did it slowly, but my eyes weren’t deceiving me. My rationality was shattered more quickly than I ever thought as I stared at a creature that I had previously believed to be mythical.

![]() The wind shifted, carrying the beast’s odor to my nostrils — a combination of excrement, old cheese, and something else, a mean smell, the kind of smell that might come from the armpit of a cantankerous deep woodsman who has caught you trespassing on his property. This wasn’t a dog but a werewolf, a monster that had previously only reigned over my dreams and memories of late night television.

The wind shifted, carrying the beast’s odor to my nostrils — a combination of excrement, old cheese, and something else, a mean smell, the kind of smell that might come from the armpit of a cantankerous deep woodsman who has caught you trespassing on his property. This wasn’t a dog but a werewolf, a monster that had previously only reigned over my dreams and memories of late night television.

![]() I was surprised at how steady my arms were as I lifted the Remington and took aim at the beast’s chest. It was barely able to take a defensive stance before I blasted a hole clean through it, the shot ricocheting around the courtyard. Its cry of pain was of the sort I hadn’t expected, more of a weak mewling sound rather than a hellish shriek, the kind an injured feline might make as it gasped its last breath in some dirty alleyway. The thing fell backward and, oddly, lay ramrod straight on the cold turf, as if set out by a mortician.

I was surprised at how steady my arms were as I lifted the Remington and took aim at the beast’s chest. It was barely able to take a defensive stance before I blasted a hole clean through it, the shot ricocheting around the courtyard. Its cry of pain was of the sort I hadn’t expected, more of a weak mewling sound rather than a hellish shriek, the kind an injured feline might make as it gasped its last breath in some dirty alleyway. The thing fell backward and, oddly, lay ramrod straight on the cold turf, as if set out by a mortician.

![]() I took a few careful steps forward, training the gun on the beast in case it hadn’t been mortally wounded by my single shot. What I witnessed made my feel as if I had just chugged a shot of liquid nitrogen, with the freezing pain starting at my mouth, working down my throat and spreading slowly through my innards. It was changing. Metamorphosing. True to the legend, the beast, upon death, was turning back into man. The hair receded, the teeth retracted, the snout caved in. And when the man’s face began to take shape and I began to recognize who it was, I dropped to my knees and began bawling like a child: it was my good friend and mentor Douglas Redmacher, Dean of the School of Liberal Arts.

I took a few careful steps forward, training the gun on the beast in case it hadn’t been mortally wounded by my single shot. What I witnessed made my feel as if I had just chugged a shot of liquid nitrogen, with the freezing pain starting at my mouth, working down my throat and spreading slowly through my innards. It was changing. Metamorphosing. True to the legend, the beast, upon death, was turning back into man. The hair receded, the teeth retracted, the snout caved in. And when the man’s face began to take shape and I began to recognize who it was, I dropped to my knees and began bawling like a child: it was my good friend and mentor Douglas Redmacher, Dean of the School of Liberal Arts.

![]() After laying my hand on Douglas’s chest and saying the Lord’s prayer, I picked up my rifle and trudged head down back into the building. The climb to the third floor felt like an eternity, slowed by my fits of sobbing and cursing. I thought I heard a siren approaching in the distance; perhaps the campus authorities had heard the rifle shot and called the local constable. No matter. The situation would be resolved shortly.

After laying my hand on Douglas’s chest and saying the Lord’s prayer, I picked up my rifle and trudged head down back into the building. The climb to the third floor felt like an eternity, slowed by my fits of sobbing and cursing. I thought I heard a siren approaching in the distance; perhaps the campus authorities had heard the rifle shot and called the local constable. No matter. The situation would be resolved shortly.

![]() In all of my adventures that eve, I had completely forgotten about Bones, who stirred ever so slightly when I entered our room. Although he seemed better, it was clear he would be in a restful slumber the rest of the night. I sat at my desk where only two hours before I had been deep in study and reflection and pondered what would come of the dreadful actions I had been forced to take. It was then I realized there was one final act to perform. I lifted the Remington with what little strength I had left and placed the business end into my mouth. I, too, wanted to rest peacefully.

In all of my adventures that eve, I had completely forgotten about Bones, who stirred ever so slightly when I entered our room. Although he seemed better, it was clear he would be in a restful slumber the rest of the night. I sat at my desk where only two hours before I had been deep in study and reflection and pondered what would come of the dreadful actions I had been forced to take. It was then I realized there was one final act to perform. I lifted the Remington with what little strength I had left and placed the business end into my mouth. I, too, wanted to rest peacefully.

![]()

![]()

![]() My name is William Wright, and I have written a short script (27 pages) entitled FORBIDDEN FRUIT. It’s the story of Adam and Eve with a modern-day twist. Of course, you know Adam and Eve from the Bible – everyone does. But how well do you really know them?

My name is William Wright, and I have written a short script (27 pages) entitled FORBIDDEN FRUIT. It’s the story of Adam and Eve with a modern-day twist. Of course, you know Adam and Eve from the Bible – everyone does. But how well do you really know them?

![]() In this version, when Adam asks God for a partner, God creates Steve. He thinks the two men will make good friends. But when the guys start getting a little too friendly, God finds himself forced to take drastic measures. He creates a woman, Eve, to quench their carnal thirst. The only thing is, Steve isn’t attracted to Eve, only to Adam. Eve is also attracted only to Adam. Adam is attracted to both Steve and Eve and feels torn between them. God is losing his patience, while the serpent licks his chops. Probably not the version you heard growing up.

In this version, when Adam asks God for a partner, God creates Steve. He thinks the two men will make good friends. But when the guys start getting a little too friendly, God finds himself forced to take drastic measures. He creates a woman, Eve, to quench their carnal thirst. The only thing is, Steve isn’t attracted to Eve, only to Adam. Eve is also attracted only to Adam. Adam is attracted to both Steve and Eve and feels torn between them. God is losing his patience, while the serpent licks his chops. Probably not the version you heard growing up.

![]() The film could be made in a week for only a few thousand dollars. Anyone interested please email me for a free copy of the script. Thank you.

The film could be made in a week for only a few thousand dollars. Anyone interested please email me for a free copy of the script. Thank you.

William Wright

bill91932@hotmail.com

![]()

I understood you today.

It swept past in an instant,

firm but gentle as hovering beyond a breaker,

gripping sand with splayed toes.

Rolling lift in warm saline,

planting me softly home.

The hands of God touched her golden child.

I gazed skyward hoping for repeat.

Aisle five’s dingy perforated tiles regarded me.

I winced at their accusation.

Selfish.

I seem the mark of all vile and foul.

This sour milk, this skull

a crucible of scrambled transmission.

So hateful am I, my name can not be spoken

within your country.

I’ve cowered at the gates while children point,

whispering in hushed awe.

Fetid mythic evil to virgin eyes.

You have banished me to aisle five.

I smelled your fear.

Not what one would expect,

it touched my face and filled my mind.

Light and thin yet tangible as custard.

I saw its face, its smile in no way unpleasant.

My own fear bullies and squeals,

pulling my hair with sticky fat infant fists.

Impatient.

Yours faced me, genteel on your behalf.

Our cheeks brushed in aisle five.

Water spun on parallel walls

while fluid roared in my brain.

Equalized.

The universal solvent surrounding, blood within.

There has been no adolescent need

to slice my borders,

achieving parity through fractional anihilation,

each score a murder.

I reel, sneakers producing painful murmurs

on aisle five’s wet linoleum.

Afraid.

I see us arm in arm, tear stained and weary.

Comrades in frosting, you once said

![]() “no one understands what we know.”

“no one understands what we know.”

I stand alone in aisle five. Rainbows right. Africa left.

![]()

![]()

![]() The camera catches Sam in the last minutes of his life. Poor guy. He will die working so hard. Sam bounces in between tables and the main counter of Pico’s Sunnyside Gourmet Deli and Diner, clearing dishes, delivering orders and getting those little extra things that customers always realize they need afterwards. In a rare lull, he is stopped by a gesture then the approach of Greg, the Diner’s manager. They talk for a while. At first, Sam bounces in front of Greg, anxious to continue his route. Then he slows, stops, and listens to Greg intently. Greg appears worried. Greg walks off camera before Sam turns full around and stops again.

The camera catches Sam in the last minutes of his life. Poor guy. He will die working so hard. Sam bounces in between tables and the main counter of Pico’s Sunnyside Gourmet Deli and Diner, clearing dishes, delivering orders and getting those little extra things that customers always realize they need afterwards. In a rare lull, he is stopped by a gesture then the approach of Greg, the Diner’s manager. They talk for a while. At first, Sam bounces in front of Greg, anxious to continue his route. Then he slows, stops, and listens to Greg intently. Greg appears worried. Greg walks off camera before Sam turns full around and stops again.

![]() One has to know to notice the lone customer, sitting at the upper right corner of the camera shot, monopolizing a table, sitting before a plate long emptied. Unless, of course, one makes note of his skin color, Eastridge black, a contrast to all the other white customers who fill the shot. Otherwise, he only catches the attention once Sam approaches him with uncharacteristically cautious urgency.

One has to know to notice the lone customer, sitting at the upper right corner of the camera shot, monopolizing a table, sitting before a plate long emptied. Unless, of course, one makes note of his skin color, Eastridge black, a contrast to all the other white customers who fill the shot. Otherwise, he only catches the attention once Sam approaches him with uncharacteristically cautious urgency.

![]() “Excuse me, sir,” a survivor would later corroborate Sam as saying. “My manager wants to know if there’s anything else we can do for you.”

“Excuse me, sir,” a survivor would later corroborate Sam as saying. “My manager wants to know if there’s anything else we can do for you.”

![]() The customer does not appear to respond. Unless one considers the pushing aside of some object or objects to the corner of the table, away from Sam, as if to clear room. One has to know to identify the objects as a syringe and a rubber cord, the kind used to temporarily cut off circulation to an arm.

The customer does not appear to respond. Unless one considers the pushing aside of some object or objects to the corner of the table, away from Sam, as if to clear room. One has to know to identify the objects as a syringe and a rubber cord, the kind used to temporarily cut off circulation to an arm.

![]() The survivor claims to have heard Sam request, “Sir, we’d like you to leave.” Those are Sam’s final words. Unless, of course, one counts the screams.

The survivor claims to have heard Sam request, “Sir, we’d like you to leave.” Those are Sam’s final words. Unless, of course, one counts the screams.

![]() In the last moments, the customer looks at the camera. He knows it is there. “Glory!” he calls through a pained grimace. And then he begins shaking. He holds his fists and arms taut in front of him, atop the table. They quake from the tension. But also from something more, for the muscles seem to ripple as if some fluid rushes below the skin. They swell from it. And the shaking grows to violence as if invisible hands hold the customer and push him back and forth, up and down with a strength beyond human.

In the last moments, the customer looks at the camera. He knows it is there. “Glory!” he calls through a pained grimace. And then he begins shaking. He holds his fists and arms taut in front of him, atop the table. They quake from the tension. But also from something more, for the muscles seem to ripple as if some fluid rushes below the skin. They swell from it. And the shaking grows to violence as if invisible hands hold the customer and push him back and forth, up and down with a strength beyond human.

![]() The other customers become agitated. Most look, some manage to stand. That is the farthest anyone gets. In that last instant, the customer’s frenzied eyes fill and spray with bursting blood and, but you have to know to see, there is the slightest hint of a smile.

The other customers become agitated. Most look, some manage to stand. That is the farthest anyone gets. In that last instant, the customer’s frenzied eyes fill and spray with bursting blood and, but you have to know to see, there is the slightest hint of a smile.

![]() Agent Damon stops the tape. He pulls at his collar, which is browning with sweat despite the cold winter day. The tape makes everyone uncomfortable. Police Captain Steffes shifts in his chair. His voice cracks when he clears his throat.

Agent Damon stops the tape. He pulls at his collar, which is browning with sweat despite the cold winter day. The tape makes everyone uncomfortable. Police Captain Steffes shifts in his chair. His voice cracks when he clears his throat.

![]() But it is Agent Damon who speaks first. “Do you know this man, Sergeant Toomes?”

But it is Agent Damon who speaks first. “Do you know this man, Sergeant Toomes?”

![]() “That’s the wrong question,” Police Sergeant Toomes answers. Despite the attention from the F.B.I. agent and his Sunnyside ally, Toomes sits secure in his chair.

“That’s the wrong question,” Police Sergeant Toomes answers. Despite the attention from the F.B.I. agent and his Sunnyside ally, Toomes sits secure in his chair.

![]() “What’s the correct question, Sergeant?” Agent Damon asks.

“What’s the correct question, Sergeant?” Agent Damon asks.

![]() “Do I recognize the symptoms? Do I know what happens next? Do I know why?”

“Do I recognize the symptoms? Do I know what happens next? Do I know why?”

![]() “And?” Captain Steffes bites.

“And?” Captain Steffes bites.

![]() “The answer is yes. I know what glory is. Show the rest of the tape.”

“The answer is yes. I know what glory is. Show the rest of the tape.”

![]() Captain Steffes looks to Agent Damon, unsure. But Agent Damon does not hesitate in obliging. Although he pulls at his collar again once the tape whirs into action.

Captain Steffes looks to Agent Damon, unsure. But Agent Damon does not hesitate in obliging. Although he pulls at his collar again once the tape whirs into action.

![]() In the video, Sam scrambles to escape, grabbing for surrounding tables and customers to speed himself away. But the monster has his bleeding eyes set on Sam as his first victim. After it looks away from the camera, it becomes a black blur. Its swelled body moves so fast. Only its jitters catch its movement like a strobe light, still-framed before a blinding fast-forward strike at Sam. The sweep of its hand appears to land partially inside Sam’s back, hooking into his meat, pulling him back into the monster’s grinder. The monster rips at Sam, tearing an arm, leg, twisting free the head, each with a geyser of blood, followed by the limbs landing against the people around them, who now scream in flight. But the monster is too fast for them. Only one person escapes before the monster leaps out of frame to cut off their path. Limbs and a steady flow of blood replace it on camera. Until it returns to dismember those in frame.

In the video, Sam scrambles to escape, grabbing for surrounding tables and customers to speed himself away. But the monster has his bleeding eyes set on Sam as his first victim. After it looks away from the camera, it becomes a black blur. Its swelled body moves so fast. Only its jitters catch its movement like a strobe light, still-framed before a blinding fast-forward strike at Sam. The sweep of its hand appears to land partially inside Sam’s back, hooking into his meat, pulling him back into the monster’s grinder. The monster rips at Sam, tearing an arm, leg, twisting free the head, each with a geyser of blood, followed by the limbs landing against the people around them, who now scream in flight. But the monster is too fast for them. Only one person escapes before the monster leaps out of frame to cut off their path. Limbs and a steady flow of blood replace it on camera. Until it returns to dismember those in frame.

![]() Agent Damon and Captain Steffes have long turned away from the screen. Sergeant Toomes joins them now. He doesn’t want to watch what happens to the children.

Agent Damon and Captain Steffes have long turned away from the screen. Sergeant Toomes joins them now. He doesn’t want to watch what happens to the children.

![]() What they don’t see, but already know, is that the monster comes to a kind of rest in the center of the carnage, pieces of furniture and people spread around it, red all over everything. Although it appears at rest, its body still moves, jerking and quivering, less violently, but faster now, like a machine that revs at a steady idle. Red line. The monster screams in triumph or pain or both as it lifts its arms at its side. Then its chest explodes outwards with such force that it breaks the ribs open and splatters its insides with a cannon burst. The shell of the monster crumbles to the floor, joining its victims.

What they don’t see, but already know, is that the monster comes to a kind of rest in the center of the carnage, pieces of furniture and people spread around it, red all over everything. Although it appears at rest, its body still moves, jerking and quivering, less violently, but faster now, like a machine that revs at a steady idle. Red line. The monster screams in triumph or pain or both as it lifts its arms at its side. Then its chest explodes outwards with such force that it breaks the ribs open and splatters its insides with a cannon burst. The shell of the monster crumbles to the floor, joining its victims.

![]() “Sergeant Roberts said it looked like Tel Aviv in there,” Captain Steffes offers. “Autopsy revealed flesh beneath his fingernails, in his teeth.”

“Sergeant Roberts said it looked like Tel Aviv in there,” Captain Steffes offers. “Autopsy revealed flesh beneath his fingernails, in his teeth.”

![]() “You can spare me the details, Captain,” Sergeant Toomes cuts him off. “I know the details. I’ve cleaned up after them too many times now. Eastridge knows glory.”

“You can spare me the details, Captain,” Sergeant Toomes cuts him off. “I know the details. I’ve cleaned up after them too many times now. Eastridge knows glory.”

![]() “Yah, but now this is happening in my city!” the white Captain responds.

“Yah, but now this is happening in my city!” the white Captain responds.

![]() The comment gets Sergeant Toomes hot. He brings a black fist down on the table before standing and pointing an accusatory finger at Captain Steffes.

The comment gets Sergeant Toomes hot. He brings a black fist down on the table before standing and pointing an accusatory finger at Captain Steffes.

![]() “Don’t you get righteously indignant with me, you donut-eating, bicycle-beat, Sunnyside snob! We’ve been dealing with glory for months! I had a woman shoot up glory at a cornerstore on Third, a guy at a city park packed with families. And I lost half my men, including my captain, when someone brought it in here. So don’t you come in here acting like you’re its biggest victim!”

“Don’t you get righteously indignant with me, you donut-eating, bicycle-beat, Sunnyside snob! We’ve been dealing with glory for months! I had a woman shoot up glory at a cornerstore on Third, a guy at a city park packed with families. And I lost half my men, including my captain, when someone brought it in here. So don’t you come in here acting like you’re its biggest victim!”

![]() Captain Steffes looks horrified. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I didn’t know.”

Captain Steffes looks horrified. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I didn’t know.”

![]() “The story didn’t get out,” Toomes explains. “Just like you two aren’t going to let this one get out. No cop wants any more people to know about this drug, or there’d be bodies lining the streets.” Sergeant Toomes calms himself and taps his finger in the air while thinking. Eventually, he asks, “That’s why you’re here, right? Because now glory is in Sunnyside. And your Sunnyside perpetrator looks Eastridge black.”

“The story didn’t get out,” Toomes explains. “Just like you two aren’t going to let this one get out. No cop wants any more people to know about this drug, or there’d be bodies lining the streets.” Sergeant Toomes calms himself and taps his finger in the air while thinking. Eventually, he asks, “That’s why you’re here, right? Because now glory is in Sunnyside. And your Sunnyside perpetrator looks Eastridge black.”

![]() The Captain’s sympathetic expression disappears.

The Captain’s sympathetic expression disappears.

![]() Agent Damon breaks in. “Let me add some other recent events, and the reason why I’m here. I’ve got a missing agent, missing about a week and a half. And since then, I’ve got a dead agent, regional upper brass, dead in his house from a glory attack. Home invasion. Seems curious though, doesn’t it? Why his house, well out of town? And an F.B.I. agent was at that diner,” he points at the television, “as she is every Tuesday at that time. Why that diner, on that day, at that time?”

Agent Damon breaks in. “Let me add some other recent events, and the reason why I’m here. I’ve got a missing agent, missing about a week and a half. And since then, I’ve got a dead agent, regional upper brass, dead in his house from a glory attack. Home invasion. Seems curious though, doesn’t it? Why his house, well out of town? And an F.B.I. agent was at that diner,” he points at the television, “as she is every Tuesday at that time. Why that diner, on that day, at that time?”

![]() “Were the perpetrators black?”

“Were the perpetrators black?”

![]() Captain Steffes answers coldly, “Yes.”

Captain Steffes answers coldly, “Yes.”

![]() “So you see a connection,” Toomes concludes. “You think this is some kind of terrorism or something.”

“So you see a connection,” Toomes concludes. “You think this is some kind of terrorism or something.”

![]() “What do you think?” Agent Damon finally asks the question for which he came.

“What do you think?” Agent Damon finally asks the question for which he came.

![]() “I think you’re wrong. They might be black, but there’s no conspiracy. Unless you call suicide a conspiracy. The two glory users you know are perpetrators, but the ones I’ve seen are victims.”

“I think you’re wrong. They might be black, but there’s no conspiracy. Unless you call suicide a conspiracy. The two glory users you know are perpetrators, but the ones I’ve seen are victims.”

![]() Agent Damon frowns, unhappy with the answer. Captain Steffes glares.

Agent Damon frowns, unhappy with the answer. Captain Steffes glares.

![]() “Take the first case,” Sergeant Toomes continues. “Ex con. Huggins. Got out of prison and moved back into the area. So I had my eyes on him. A lot of people did. But it didn’t turn out to be the typical situation where the con gets back in with the bad crowd. This guy was really trying to make good. Only me and the others didn’t give him much of a chance. I was riding him every day. And that didn’t help him much with the neighbors. People were suspicious at best, cruel at worst. And like most cons, he didn’t have much luck getting a real job. Maybe he could have worked at a chain store. You know, where they don’t need to know you too well to hire you. But there aren’t many of those around here. Even if there were, are they going to hire a bulked out black brother with tats and scars? No, his best shot was his former friends. But he really wanted to be better than that. He had no chance.

“Take the first case,” Sergeant Toomes continues. “Ex con. Huggins. Got out of prison and moved back into the area. So I had my eyes on him. A lot of people did. But it didn’t turn out to be the typical situation where the con gets back in with the bad crowd. This guy was really trying to make good. Only me and the others didn’t give him much of a chance. I was riding him every day. And that didn’t help him much with the neighbors. People were suspicious at best, cruel at worst. And like most cons, he didn’t have much luck getting a real job. Maybe he could have worked at a chain store. You know, where they don’t need to know you too well to hire you. But there aren’t many of those around here. Even if there were, are they going to hire a bulked out black brother with tats and scars? No, his best shot was his former friends. But he really wanted to be better than that. He had no chance.

![]() “But even so, I really don’t think he meant to hurt anybody. Because when he shot glory, he piled furniture at the front door of his apartment. He just wanted to end it all, maybe rip himself to shreds. But he forgot to block the window. He jumped three stories and shattered a leg and still kept going enough to tear four people apart and pull two others out of their cars before he exploded.”

“But even so, I really don’t think he meant to hurt anybody. Because when he shot glory, he piled furniture at the front door of his apartment. He just wanted to end it all, maybe rip himself to shreds. But he forgot to block the window. He jumped three stories and shattered a leg and still kept going enough to tear four people apart and pull two others out of their cars before he exploded.”

![]() Agent Damon frowns. Captain Steffes face grows more pale.

Agent Damon frowns. Captain Steffes face grows more pale.

![]() Sergeant Toomes continues, “Second case was a drug user. I figure someone sold it to him as heroin, or gave it to him free. I mean, is a heroin user going to pay for a drug he hasn’t even tried? A drug that isn’t heroin? Or, who knows, maybe he knew what he was doing. But the events suggest it wasn’t planned mass suicide.”

Sergeant Toomes continues, “Second case was a drug user. I figure someone sold it to him as heroin, or gave it to him free. I mean, is a heroin user going to pay for a drug he hasn’t even tried? A drug that isn’t heroin? Or, who knows, maybe he knew what he was doing. But the events suggest it wasn’t planned mass suicide.”

![]() “Mass suicide?” Captain Steffes asks.

“Mass suicide?” Captain Steffes asks.

![]() “The junkie brought glory to a crack house, enough of it for a small party, and shared it with the people there. When the five glory shooters tore everyone else apart, they went at each other. Three didn’t stay together long enough to explode.

“The junkie brought glory to a crack house, enough of it for a small party, and shared it with the people there. When the five glory shooters tore everyone else apart, they went at each other. Three didn’t stay together long enough to explode.

![]() “And that’s when I started thinking. This doesn’t make any sense. What’s the use of a drug that doesn’t keep its customers? I mean, how can any dealer profit off that? As you can imagine, at that point my goal was to get the drug dealer. But how can you find him when every user dies after one hit? I was stuck.

“And that’s when I started thinking. This doesn’t make any sense. What’s the use of a drug that doesn’t keep its customers? I mean, how can any dealer profit off that? As you can imagine, at that point my goal was to get the drug dealer. But how can you find him when every user dies after one hit? I was stuck.

![]() “Then came Randy. I knew Randy well, since he was a kid. Poor guy had a hard life. All made worse by mental problems: anxiety and depression. Made it really hard on his wife. Especially when he was committed. She was my sister. Left her with two kids and no wage earner. I tried to help out, but I’ve got my own family.

“Then came Randy. I knew Randy well, since he was a kid. Poor guy had a hard life. All made worse by mental problems: anxiety and depression. Made it really hard on his wife. Especially when he was committed. She was my sister. Left her with two kids and no wage earner. I tried to help out, but I’ve got my own family.