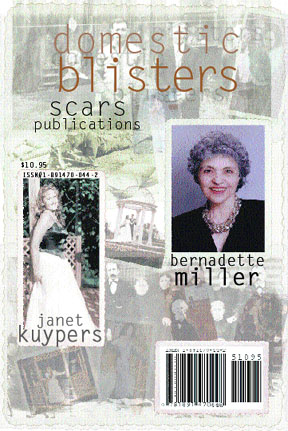

About Bernadette Miller