|

Dusty Dog Reviews The whole project is hip, anti-academic, the poetry of reluctant grown-ups, picking noses in church. An enjoyable romp! Though also serious. |

|

Nick DiSpoldo, Small Press Review (on Children, Churches and Daddies, April 1997) Children, Churches and Daddies is eclectic, alive and is as contemporary as tomorrow’s news. |

|

Kenneth DiMaggio (on cc&d, April 2011) CC&D continues to have an edge with intelligence. It seems like a lot of poetry and small press publications are getting more conservative or just playing it too academically safe. Once in awhile I come across a self-advertized journal on the edge, but the problem is that some of the work just tries to shock you for the hell of it, and only ends up embarrassing you the reader. CC&D has a nice balance; [the] publication takes risks, but can thankfully take them without the juvenile attempt to shock. |

Volume 226, November 2011

Children, Churches and Daddies (cc&d)

The Unreligious, Non-Family-Oriented Literary and Art Magazine

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

Cover art by Peter LaBerge

(who also has artwork at flickr)

see what’s in this issue...

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

|

Order this issue from our printer as a a $7.57 paperback book (5.5" x 8.5") perfect-bound w/ b&w pages You can also get this from our printer as a a ISBN# paperback book (6" x 9") perfect-bound w/ b&w pages titled No Return: |

from “Watching the World” in March 2011 Awake! magazineTrust in Church Had Plummeted“Most people no longer trust [the Catholic] Church,” says a headline in the Irish Times. The report places the Catholic Church in the same category as other institutions in which a majority of the Irish have lost confidence–the government and the banks. In a country where loyalty to the church has been legendary, over half those interviewed in a recent poll said either that they did not trust the church “at all” (32%) or that they did “not really” trust the church (21%). Scandals that have recently rocked the church are blamed for the fact that public trust in it has “plummeted.”

|

poetry

the passionate stuff

My Conversations with Death:

Mel Waldman |

BIOMel Waldman, Ph. D.Dr. Mel Waldman is a licensed New York State psychologist and a candidate in Psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies (CMPS). He is also a poet, writer, artist, and singer/songwriter. After 9/11, he wrote 4 songs, including “Our Song,” which addresses the tragedy. His stories have appeared in numerous literary reviews and commercial magazines including HAPPY, SWEET ANNIE PRESS, CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES and DOWN IN THE DIRT (SCARS PUBLICATIONS), NEW THOUGHT JOURNAL, THE BROOKLYN LITERARY REVIEW, HARDBOILED, HARDBOILED DETECTIVE, DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE, ESPIONAGE, and THE SAINT. He is a past winner of the literary GRADIVA AWARD in Psychoanalysis and was nominated for a PUSHCART PRIZE in literature. Periodically, he has given poetry and prose readings and has appeared on national T.V. and cable T.V. He is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Private Eye Writers of America, American Mensa, Ltd., and the American Psychological Association. He is currently working on a mystery novel inspired by Freud’s case studies. Who Killed the Heartbreak Kid?, a mystery novel, was published by iUniverse in February 2006. It can be purchased at www.iuniverse.com/bookstore/, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. Recently, some of his poems have appeared online in THE JERUSALEM POST. Dark Soul of the Millennium, a collection of plays and poetry, was published by World Audience, Inc. in January 2007. It can be purchased at www.worldaudience.org, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. A 7-volume short story collection was published by World Audience, Inc. in June 2007 and can also be purchased online at the above-mentioned sites. |

What Aesha said

Kelley Jean White MD |

When I find Jesoo in the gutter,Fritz Hamilton

When I find Jesoo in the gutter,

slurs his words, “The congress wouldn’t

went back to my favorite addiction, which

asks me for some bread for wine, but

stump, & I think that’s the way to go, but

Muhammed, because Jesoo’s getting !

|

My nose is running, &Fritz Hamilton

My nose is running, &

sidewalk/ my bones mix

pray to Jesoo to save my

street like a sheep who’s

with my nose he catches like

homeless like everybody

about it, which is to

nose that ran will be

! (so

|

SighDan Fitzgerald

An exhalation

|

image by John Yotko

End of the Year - Business Style.Matthew Roberts

There’s smoke on my plate

important men with expensive

|

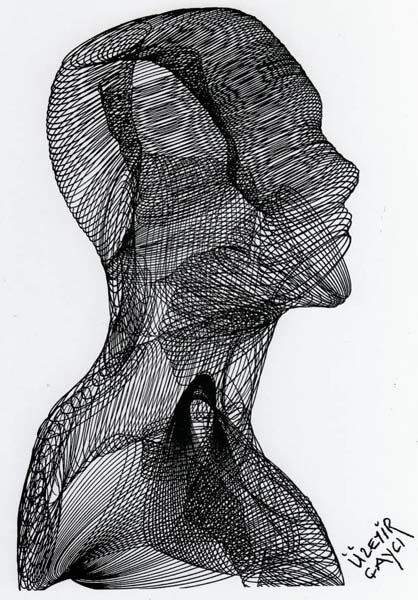

Art 384 K, by Üzeyir Lokman ÇAYCI

Virgins Gale Acuff

I know where the dead go, I mean, when they

up, I don’t know why, I couldn’t feel my

I’m a poet and not just a preacher

at any time, even when our time’s not

if so then they’re not perfect so how can God

Miss Hooker after class. Last Sunday I

was Sunday morning and time for our class.

down at Miss Hooker’s open-toe shoes and

could see the tops of her chests and that place

Miss Hooker. Then she said, I love you, too,

which seems a lot to ask of me to learn

again, I want to die and get life right

|

NewspapersMaxwell BaumbachI wish newspapers were interesting

the business section

talking about the environment

world news is stupid.

newspapers should talk more about celebrities

you know,

|

Poem From

Kenneth DiMaggio |

| John Yotko reads the Kenneth DiMaggio 11/11 cc&d poem Poem from the Hartford Epic: Kids from the cc&d collection book Fragments |

Watch this YouTube video read live 12/04/11, at the Café weekly poetry open mike in Chicago |

First to Fight, Die or BuyDavid S. Pointer

A beach mounted machine gun

|

Duikboot, ar by the HA!man of South Africa

The Avant-Garde Swan SongLisa Cappiello

You take a giant step to avoid the mahogany framed full-length mirror

|

from

The De-Greening of America,

Michael Ceraolo |

GovernmentEric Shelman

Giving into others’ plans to deceive their country

|

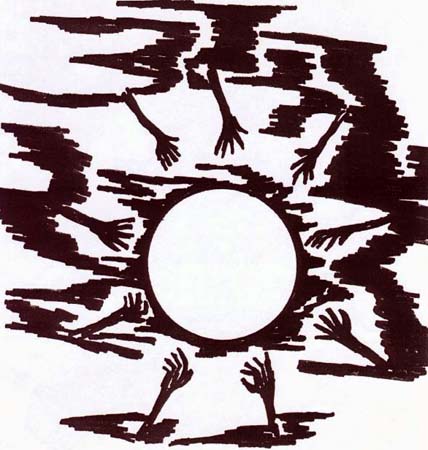

Need, art by Edward Michael O’Durr Supranowicz

Seal WatchingMatthew Guzman

After the pub,

Dublin air keeps our sway & swagger

Rolling our cigarettes,

You whistled like a canary,

|

Before it Occurred to MeJanet Kuypers03/29/11

as the extra kitchen cleanser the fumes rose

i opened a window coughed

before it occurred to me

no, i’m no Nazi

and sometimes

|

On a Downtown Chicago Light PoleJanet Kuypers04/05/11

Saw a sticker

someone wrote

|

one by one, the beech trees fellJanet Kuypers03/11/11

i have lived at this grove all my life

everything was blooming by the end of May

could hear noise in the distance one morning

Rommel was sure an attack was immanent

looked out the front door, saw our stripped land

they didn’t do this everywhere:

what lives are worth saving, i thought

|

No ReturnJohn Grey

There comes a point where I realize that train’s not coming back,

When I was younger, I was more attuned to the side

But eventually, I threw in my lot with moving vehicles

So I live in the side of a house. I inhabit a rock.

|

August Regatta AfternoonWilliam Doreski

Not like shark fins but napkins

the boats look like punctuation

This is how the gentry live—

we’ll learn who won, if we care.

sparkling in our frosty glasses

|

Mandy on the South SideMark D. Cohen

I saw Mandy crossing South Park St. from West to East

Actually, I don’t know her real name—

She was extraordinarily beautiful,

Mandy is a white woman in a “colored” neighbor— But European-Americans (like Mandy) are definitely in the minority

Mandy had a lot of energy—

I was glad to watch Mandy through my car window

|

Translucent Brick, art by Rose E. Grier

Birds: The BluebirdSarah Lucille Marchant

the bluebird picks through the snow

red, hardened with age,

the bluebird’s eyes no longer shine

‘neath layers of tainted snow

|

Birds: The BlackbirdSarah Lucille Marchant

the blackbird digs through the sky the blackbird releases his spirit in a wisp

breathing out senses

|

FragmentsDeborah Nodler Rosen

We are all Lot’s wife, Orpheus,

|

adviceEmerald Scott

just play with your kids

you love to wade in misery

forget the man

|

Two images photographed in Washington state by Brian Hosey

Letter to Suicide (an old friend)Emma Eden Ramos

We go way back.

Passing the mostly gone window, I heard the sound of crackling egg fat when yoke hits the butter laden pan.

I saw him then,

We met first then

So I’m writing you now like an Irishman signaling the banshee.

Cancer has me most of the time.

|

Emma Eden Ramos Bio (2010)Emma Eden Ramos is a writer and student at Marymount Manhattan College in New York City. Her fiction has appeared in BlazeVOX, The Legendary, and The StoryTeller Tymes. She also has a piece forthcoming in Yellow Mama.

|

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

Proper ToolsRichard E Marion

It’s simple. Travel light. Do the work using the proper tools.

|

Coffee Grinds in ParadiseLinda Webb Aceto

I had to go. I was court committed to Western State Hospital for Mental Illness during that podunk hearing, brought together to decide my fate. The judge said that there was an alcohol and drug treatment center there, and he had noticed that, along with my psychotic episode, I also had a slight problem with alcohol. Perceptive little man.

There was a sputtering gasp around the room. My father began to speak, “She doesn’t really need that...” but I interrupted him, saying, “Yes, I want to go there. I’m an alcoholic, and I need treatment”. Little did I know about state hospitals.

The transfer ended at a hulking mass of red brick buildings with locked doors and barred windows. The sprawled out campus was tightly girdled by escape proof cyclone fencing. Once inside the hospital grounds, I was unceremoniously dumped in the waiting room of the admissions office, still doped, but un-cuffed, while the staff papered and processed me into the system. I dozed, skittered in and out of reality, dozed a bit more, then ate the food they brought me. Very kind of them, I thought, serving me like that. More of that pesky state of delusion. Once I was housed in the ward, I would be brought my food for quite a while, since I was not allowed past the locked door, not even to go to the cafeteria.

I was in hog heaven. Not only was I the only woman, I was still very pretty in the bleary, besotted eyes of my fellow inmates. They courted me, did my chores; one relatively cute guy brought me a cookie. I thought I might be in love until I noticed that he had no teeth, a definite deal breaker. Still, the attention was nice, and I was manic enough to not notice the truth of my surroundings. We played cards for diversion from that truth. There was a pool table, and mock AA meetings edged us toward recovery of some sort or other. We also played volleyball, but I irritated the piss out of the program director for ducking each time the ball came my way, In fact, I irritated him all the time. I did not mean to be the way I was—manic, happy as a fool, having a good, old time.

At first it wasn’t so bad. Still on heavy duty psychiatric drugs, I shuffled and drooled, explored the ward, and engaged in meaningless conversations with my new room-mates. I still dozed a lot, a welcomed diversion. Time passed pleasantly enough.

In the women’s ward, the events were far less violent and often more amusing. One woman put lipstick on her cheeks to entice men to “take her to the bushes”, while Shirley simply had no teeth as a calling card for her suitors. Gnarled old women, waiting for their passage to the ward for the demented, snatched cigarettes from those who were not so quick or alert. I sat and ate bags of hard candies and drank my coffee sludge, watching and waiting for some sport that might perk up the hours.

That was it. Mostly we just sat and smoked, bartered for food, and hoped that a visitor might come, or even just mail.

I think that my parents came once during my 5 month hospitalization, but I don’t recall anything memorable about it other than my father peeking around corners, trying to get a good look at the residing madness. He was as misguided as the boy. All he had to do was look at me.

Some of the aides were very kind and attentive. I got my hair done up by one who had been a hair dresser. (Like the word retarded, we still used those demeaning names.) I got so that I could leave the ward by myself for meals and other outside activities. I wandered throughout the grounds, I tested the musings in the library, and I found the art therapy room, a place where I could play without reservation. We were carefully monitored as we cut, pasted, and/or painted our treasures—creations that were basic enough for our simple minds and safe enough for our craftiness. I still have the little box that I stained. I pasted on a smiley picture of the sun, adding lacquer to guarantee its trip to my future. Good times.

|

The Birthday PartyRobert Turner

I was standing in front of Woolworth’s on Main Street on the fifth of October, 1943 when I began to realize how things worked in our town. James, my seventh grade classmate, and I were watching an olive skinned yo-yo master, in a bright yellow silk shirt and crimson trousers, rock a spinning red disk back and forth on a string extended between his fingers. He allowed it to fall, and just as its momentum seemed spent, retrieved it with a flick of his middle finger into the palm of his right hand. The crowd applauded as the master, who was not much taller than I, removed his white cowboy hat, bowed, and extended one sequined arm toward the store entrance.

|

Robert Turner Brief BioRobert Turner, M.D., was born in New Jersey and grew up on the Chattahoochee River in West Georgia and East Alabama. His work has appeared in a variety of medical publications and his short fiction has been published and is forthcoming in several literary magazines. He lives with his wife in West Palm Beach, Florida, where he is at work on his first novel.

|

“Interrogate My Heart InsteadElaheh Steinke

To each and every person who fought for freedom.

He has forgotten that he used to exist and that he used to love him. He doesn’t even think about him while taking a shower. They have told him that if he stabs people in the chest or hits them in the streets of his own hometown, he would make God happy.

She’s strong, beautiful even with the blindfold on, held together and ready. He doesn’t like the last part, READY. Readiness makes it hard to get over a genius mind. She won’t suffer, she won’t scream, she wouldn’t beg. He doesn’t like it. He has seen hundreds of young girls in the torture room. They all expect to be saved; saved by a call, a miracle, saved by God. But this one, this girl, she’s ready for everything to happen. The blindfold has made her even scarier.

He wakes up from a dreamless sleep. It is weekend but he has bones to crush, smiles to make disappear, lives to get. It’s a new day, it’s a new dawn and he’s goanna be a step closer to heaven and God.

Ali is in the other room; they call it “The Second Unit” of the city’s prison. They say if you get in there, there would be no way back. You’ll be gone forever. And that’s exactly where he is right now: Nowhere.

Dear Darius,

|

Elaheh Steinke BioElaheh Steinke is a 23-year-old story writer. She studies Genetics at Tehran University and teaches English. Some of her previously published works are “IWIHKY Disorder”, “No Exception”, “Falling for the Second Time”, “When the Day Is Blue, I’m Sitting Here Wondering about You”, and “January Went Lost”. She has published her works at Best New Writing 2009 and 2010 and has been the Hoffer award finalist of 2009/2010.

|

Capping, art by Oz Hardwick

MudAmanda ThossShe rifled through the leaves of the Dream Book. She had dreamt last night that she had had a baby, and bit her lip as she searched for what it could mean. Her friends had always told her these books were a load of crock, and that dreams didn’t mean anything. She usually agreed.

Her work was not tedious, and she performed well enough at it. She made sure to nod to Maggie when she showed off the photos of her children, agree when Thomas told her stories about his boss, console Becky about her break up. She ate her lunch at her desk, watching everyone else leave in groups, talking to one another.

|

Palete Peony, art by Cheryl Townsend

The Price of HonorBrian MontalbanoMy name is unimportant. My time is inconsequential. Where I live makes no difference. The only thing that matters is the events that take place. Resemblances may remain, but each person who reads these words is free to interpret it the way they wish. Stripped away of setting, the meaning still remains. Technology may improve and tactics change, but what war is will and always has been the same. War brings out the most basic of human instinct: To kill or to die. One’s mind enters insanity and whoever can control that insanity will come out the victor. There has rarely been a time in human history where society was at complete peace. There have been armed conflicts littered across our history books, making us ask the question: What is human nature? Is it to fight or is it to make peace? Peace continues to lead to more fighting, so perhaps it is in our nature to kill. Inside every person there is the ability to defend oneself, but what happens at war is an animal all its own. This is the story of the human’s mind at war.

Impending Gloom

Musket balls are flying all around. With each one that doesn’t hit me I can’t help but almost feel disappointed. Anticipation is the worst part of the battle; it’s nerve-racking not knowing whether you’re going to live or die. For every ball I send racing out of my barrel I know two more are flying back at me. Those are usually the numbers we face; I don’t think I’ve been on a battlefield when we weren’t outnumbered. I fire shot after shot, slowly forgetting the reasons behind each one. Standing next to me is my childhood friend. We enlisted together back when the revolution was something to believe in. I was young and naîve then; that was six months ago. Wars have a way of changing people, and I don’t mean that in a tough, macho, right of passage kind of way. They wear down your spirit, test the edge of your sanity, and most of all measure just how far your faith can take you. They don’t tell you that when you enlist. There were promises of glory and honor; so far I’ve only witnessed the silent promisedeath.

Then There was One

“What’s it say in the letter?” my friend asks following my long silence. “My brother,” I respond without even looking up from the letter “he’s dead.” This has been an all too common theme recently. Before I enlisted, we got word that my eldest brother died on the battlefield. It broke my mother’s heart. Every day from then on she would look out the window, scared to see another messenger coming. Every time my other brothers would send a letter home she would almost collapse when the courier dropped the mail off. It was heart wrenching to take the letters not knowing what news they contained inside. A letter came home a month before I enlisted, telling us that one of my other brothers had been killed. He was the one closest to me. He was older than me by two years and he always stood up for me. We did everything together when we were little. He was like my guardian angel, I guess his wings have been clipped. His death was hard for me to bear.

From the HeartTo My Love, This will be the first letter I write and I’m beginning to fear it will be my last. It has been hard to get a hold of paper and some ink, but I was determined to get this out to you. With every day I spend freezing out here is one more day I lose with you. I long to see your gorgeous face and stare deep into your eyes. It’s been one-hundred and twenty nine days since the last time I saw you, since that bleak day I left for training. I picked the worst time to join up. We were already losing the revolution when I joined and the days were just starting to get turn cold. It’s been a dreadfully long winter. The nights can get so bitterly cold, the only thing that keeps me alive is to think of the warmth of your heart. In the beginning, I was optimistic and feeling patriotic. Now I feel downtrodden and my actions, futile. Each day I have more reason to grieve than the last. I have heard that all three of my brothers have been slain and my dear friend since youth fell in the last battle. I am the last of my line without a friend in this dreadful place. I never knew hell could be so frigid. I ache for this war to be over, but I’m not sure I care which side wins anymore. I just want to be back at home with you in my arms. I don’t regret joining the cause; I just see through the lies that the propagandists have told me. As long as my countrymen fight, I shall be right there beside them. I remain here because it is my duty as a citizen, but I do not believe anymore, quite frankly I don’t think many men do. The problem is, giving up and quitting just isn’t something our pride will allow. We would wait until we all perished before we accepted defeat. Some days it seems like that is the course fate has decided for us. I can’t remember the last time we won a battle, or even gained a little ground, but we fight on with what dignity we have left. I feel I will be returning to you soon, we can’t keep this up for much longer. My heart mourns every moment I am without you, but I hope that is something I can remedy. I will never stop loving you and I promise I will return to you soon. I love you with all my heart and soul.

Sincerely, A Hopeless Battle

I can hear the muskets firing all around me, but it doesn’t affect me anymore. There was once a time when I would get startled as a musket ball flew by my head, but I’m too cold now to even flinch. This war has dragged on for too long. No one knows the cause anymore; they just fight and die. The next round of muskets fire around me, but it never really matters how much we shoot. The enemy advances, overwhelms us, moves on to the next battalion, and does it again. This is not how to win independence; this is how you kill an entire generation of good men. They have more men, more guns, and more supplies. We have no chance, but our “revolutionary leaders” think it’s better to send our men to die for the cause. “It’s better to die trying to obtain freedom than to die under the tyranny and oppression of another country,” all the officers say. I think they have just been brainwashed to say that. Every officer will give you the same iteration. I’m not even sure they know what they’re saying. The generals like to make speeches to raise the morale, but they talk bout “fighting for the cause” and how “dieing for our freedom is honorable” when I don’t see them doing anything of the sort. They sit comfortably in the warmth of their mansions as we freeze on a battlefield, barely able to grasp our muskets. The only warmth we get is grasping the warm barrel of our muskets while we reload or the feeling of a searing, hot musket ball burning through our flesh.

A Field of Red

Light, so much light. It blinds my eyes. Am I dead? Is this heaven? I feel cold. The feeling returns to my hand and my arm and my legs. A sharp pain rushes through my head, like I’ve been hit in the head with a shovel. I’m not dead. A little shaken up, I manage to stagger to my feet. Quickly scanning my body, I seem to be fine. No blood or bullet holes, just a cut on my forehead. I try to move, but nearly fall again. I stand upon a sheet of ice, which caused my fall. I look down at my feet and notice rocks protruding through the ice. I must have hit one of them on the way down and was knocked unconscious. But how was I not taken prisoner? Where has everyone gone? The field has been abandoned.

Home Sweet Home

There’s my village, calm and serene. They all know nothing of yesterdaym that our army has failed and has been massacred. How could they know? With no one alive, no messenger could bring the news. I will have to reveal this gruesome event to everyone. I’m not sure I have come to terms with it enough to utter such a horror. Maybe this is all a bad dream and I will wake up any second. This nightmare is far from over. The lone soldier who is ‘privileged’ enough to return to his people, the one who will linger long after all the ones he fought with have perished. My journey is at last over for my body, but the journey of my soul is about to begin.

Inner Toil

I wake up in my own bed for the first time since I can even remember. I’m the only man in my army that has that luxury. My comrades woke up at the golden gates of heaven, while my soul awoke burning in one of the deepest circles of hell. My thoughts once again drift back to me being the only one. I am the only one living from my unit and, no matter what I do, that’s where my mind winds up. I wish I could eradicate these thoughts from my mind that have plagued my dreams and wake me in the night. This is the life I have returned to; nothing but pain and torture. The ghosts of the fallen poison my mind, haunt my dreams, and drain my soul. I have become an empty shell of a man. Will the brouhaha ever cease? Will my mind ever be able to cope with the death of my comrades? I wish it would all just stop.

Broken Silence

It’s the middle of the night. Everyone is sleeping soundly in their beds. I lay awake staring into the darkness of my ceiling; I find no peace under the shade of night. Even in total darkness I can see the images of all those dead soldiers. They’re burned into my head. They’re all I can see, never letting me sleep. I close my eyes, but that’s no escape. Closing my eyes just enhances their image. They stare at mecall out to me to join them. It’s so inviting and yet I am stuck among the living. What kind of man wishes death upon himself? Most people would be glad they survived, but I am just tormented. It’s been nearly a week I think. I haven’t truly slept a single night. Insomnia, awake when I want to sleep, yet when I’m awake I feel like I’m sleeping. Nearly one week and I haven’t said a word to my father nor has he said anything past his first, scathing remark.

Paternal Confession

I stand in the doorway, silent and confused. It seems fitting, that the only two things my father have said to me have been bitter and mean. He always was hard on me, pushed me as far as I could go. No matter what I did it seemed he expected better of me, but I grew to accept that. “What have I done father?” I ask turning and staring him in the face. “You disgraced the army!” he screams, slamming the hammer down on the anvil.

Final Goodbye

So the village thinks I’m a coward; they think that I fled in the face of adversity and danger? Could I tell them the truth that everyone fled? What is my honor worth? Can I seriously reveal the truth just to clear my name? Do I even deserve that? No no one must know. I can’t ruin the reputation of all those men, all my comrades, all my friends. They died as heroes to their country, who am I to take that away? It’s a secret only the gravediggers know, and that is the way it shall remain. But how can I live with the entire village hating me and thinking me a deserter? How can I expect the village to forgive me, when my own father will not? I believe he will never forgive me and I could tell in his voice that no part of him wishes me to be here. There is no worse feeling in the world. “I’m sorry,” are the only words that I can find to say as I walk out the door, a bastard child.

The End of the Line

An enemy fort is not too far from my village. I might as well go out just like my comrades did in my uniform with my musket in hand. The outpost is a two day’s journey and it will not be an easy one on my soul. When you stand on a battlefield, you know there is a good chance you won’t walk off alive, but there is still the chance that you can. I now go to the enemy fort knowing that I have no choice but death and that’s a sobering thought. This is such a final decision, yet I know it is right. There is no question in my mind this is what I must do. I will finally be at peace, once I face my demons.

|

Jack-O SockJ. Kent Allred

I’ll usually start with my best ‘80s moon-walk across the kitchen floor, the tile cold and smooth against my thin dress-socks, the lack of traction makes the illusion more believable. I am a large, Caucasian male and not the least bit elegant. I coax my 6 and 4 year-olds to come to me in my best mezzo-soprano, “Hey, kids, come see Neverland Ranch.”

|

Portrait of the Artists Highest Potential, art by Aaron Wilder

the Slaughterhouse of Lambs

Writing Copyright © 2011 Ned Haggard |

Greta, painting by Brian Forrest

Afterthoughts

the Real Messages in News StoriesJanet Kuypers04/04/11

So I was watching one of the new channels (I think it was MSNBC), and a woman reporting stated that there was the 4 year-old boy who was trapped in Guatemala. She is from New York, but after visiting Guatemala with her grandfather, they were stopped at Dulles International Airport when they found out that her grandfather had an illegal U.S. entry charge from more than a decade ago. So they wouldn’t let her (Emily is her name) continue home, and she had to go with her grandfather back to Guatemala.

I mean, she said Emily’s father was an illegal immigrant to the United States. Not that he was born south of the border and is living here on a work VISA, or that he married an American woman. So when I started to look up more information on this story, I saw that her grandfather was a non-citizen on a valid work visa that allowed him to travel. THEN I read that her parents (the ones illegally living in the United States, that are here in New York that they apparently are not deporting) either had to have Emily sent to Guatemala, or allow officials to put her in a juvenile facility in the United States, where she could be put in foster care (or otherwise kept away from her parents). I then read in the Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/03/23/federal-officials-4-year-old-us-citizen_n_839700.html) “If Emily’s parents had gone to pick up their daughter from authorities, they could have risked deportation along with her grandfather.” From the Huffington Post I also read: “Rep. Steve Israel (D-N.Y.) intervened on behalf of the Ruiz family on Tuesday, sending a letter to DHS calling for them to return the girl to her mother and father. ... “This bureaucratic overreach and utter failure of commonsense has left a little girl -- a U.S. citizen no less -- stranded thousands of miles from her parents,” Israel said in a statement. “I’m working with the family and their attorney to reunite Emily and her parents and asking for DHS to do a formal review of how this could have happened.”

Most Republicans would probably tell you exactly how this happened: an illegal immigrant couple decided to have baby of their born in the United States so they would have an anchor baby as an excuse to stay here. And I was surprised that the report I saw on television did not highlight that this infant girl had an entire family of people who did not have U.S. Citizenship. I often write these editorial/essays by finishing with more questions. But I wonder with this story, if I am the only one who thinks more about the fact that people had a child here to try to legitimize their existence in this country when they are not U.S. Citizens, and more importantly, does anyone else think about the fact that people are not working on removing he illegal immigrants from this country instead of shipping the 4 year-old to a country that is not her own.

|

Debra Purdy Kong, writer, British Columbia, Canada I like the magazine a lot. I like the spacious lay-out and the different coloured pages and the variety of writer’s styles. Too many literary magazines read as if everyone graduated from the same course. We need to collect more voices like these and send them everywhere.

Children, Churches and Daddies. It speaks for itself. Write to Scars Publications to submit poetry, prose and artwork to Children, Churches and Daddies literary magazine, or to inquire about having your own chapbook, and maybe a few reviews like these.

what is veganism? A vegan (VEE-gun) is someone who does not consume any animal products. While vegetarians avoid flesh foods, vegans don’t consume dairy or egg products, as well as animal products in clothing and other sources. why veganism? This cruelty-free lifestyle provides many benefits, to animals, the environment and to ourselves. The meat and dairy industry abuses billions of animals. Animal agriculture takes an enormous toll on the land. Consumtion of animal products has been linked to heart disease, colon and breast cancer, osteoporosis, diabetes and a host of other conditions. so what is vegan action?

We can succeed in shifting agriculture away from factory farming, saving millions, or even billions of chickens, cows, pigs, sheep turkeys and other animals from cruelty. A vegan, cruelty-free lifestyle may be the most important step a person can take towards creatin a more just and compassionate society. Contact us for membership information, t-shirt sales or donations.

vegan action

Children, Churches and Daddies no longer distributes free contributor’s copies of issues. In order to receive issues of Children, Churches and Daddies, contact Janet Kuypers at the cc&d e-mail addres. Free electronic subscriptions are available via email. All you need to do is email ccandd@scars.tv... and ask to be added to the free cc+d electronic subscription mailing list. And you can still see issues every month at the Children, Churches and Daddies website, located at http://scars.tv

MIT Vegetarian Support Group (VSG)

functions: We also have a discussion group for all issues related to vegetarianism, which currently has about 150 members, many of whom are outside the Boston area. The group is focusing more toward outreach and evolving from what it has been in years past. We welcome new members, as well as the opportunity to inform people about the benefits of vegetarianism, to our health, the environment, animal welfare, and a variety of other issues.

Dusty Dog Reviews: These poems document a very complicated internal response to the feminine side of social existence. And as the book proceeds the poems become increasingly psychologically complex and, ultimately, fascinating and genuinely rewarding.

Dusty Dog Reviews: She opens with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, CA Indeed, there’s a healthy balance here between wit and dark vision, romance and reality, just as there’s a good balance between words and graphics. The work shows brave self-exploration, and serves as a reminder of mortality and the fragile beauty of friendship.

Mark Blickley, writer You Have to be Published to be Appreciated. Do you want to be heard? Contact Children, Churches and Daddies about book or chapbook publishing. These reviews can be yours. Scars Publications, attention J. Kuypers. We’re only an e-mail away. Write to us.

The Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology The Solar Energy Research & Education Foundation (SEREF), a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C., established on Earth Day 1993 the Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology (CREST) as its central project. CREST’s three principal projects are to provide: * on-site training and education workshops on the sustainable development interconnections of energy, economics and environment; * on-line distance learning/training resources on CREST’s SOLSTICE computer, available from 144 countries through email and the Internet; * on-disc training and educational resources through the use of interactive multimedia applications on CD-ROM computer discs - showcasing current achievements and future opportunities in sustainable energy development. The CREST staff also does “on the road” presentations, demonstrations, and workshops showcasing its activities and available resources. For More Information Please Contact: Deborah Anderson dja@crest.org or (202) 289-0061

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA want a review like this? contact scars about getting your own book published.

The magazine Children Churches and Daddies is Copyright © 1993 through 2011 Scars Publications and Design. The rights of the individual pieces remain with the authors. No material may be reprinted without express permission from the author.

Okay, nilla wafer. Listen up and listen good. How to save your life. Submit, or I’ll have to kill you.

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA: “Hope Chest in the Attic” captures the complexity of human nature and reveals startling yet profound discernments about the travesties that surge through the course of life. This collection of poetry, prose and artwork reflects sensitivity toward feminist issues concerning abuse, sexism and equality. It also probes the emotional torrent that people may experience as a reaction to the delicate topics of death, love and family. “Chain Smoking” depicts the emotional distress that afflicted a friend while he struggled to clarify his sexual ambiguity. Not only does this thought-provoking profile address the plight that homosexuals face in a homophobic society, it also characterizes the essence of friendship. “The room of the rape” is a passionate representation of the suffering rape victims experience. Vivid descriptions, rich symbolism, and candid expressions paint a shocking portrait of victory over the gripping fear that consumes the soul after a painful exploitation.

Dusty Dog Reviews (on Without You): She open with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

|

“Yeah, lets get started cooking them,” I said, glad in a way more of the fifteen people in our class hadn’t come since Eugene only had one package of frankfurters. I knew I was too fat and overly concerned with food. Size had been an advantage when I was younger. As a midget football lineman, I had been able to block out the smaller boys, but now that they were taller and quicker and I was having trouble keeping up with Cranston, James, and the others. Our school was on a hill overlooking the town and it housed all twelve grades. A plateau just outside the old building was our playground where we ran around at recess. Lately the other kids had been turning on me, calling me names and chasing me. I was feeling more like an outsider than ever.

“Yeah, lets get started cooking them,” I said, glad in a way more of the fifteen people in our class hadn’t come since Eugene only had one package of frankfurters. I knew I was too fat and overly concerned with food. Size had been an advantage when I was younger. As a midget football lineman, I had been able to block out the smaller boys, but now that they were taller and quicker and I was having trouble keeping up with Cranston, James, and the others. Our school was on a hill overlooking the town and it housed all twelve grades. A plateau just outside the old building was our playground where we ran around at recess. Lately the other kids had been turning on me, calling me names and chasing me. I was feeling more like an outsider than ever.