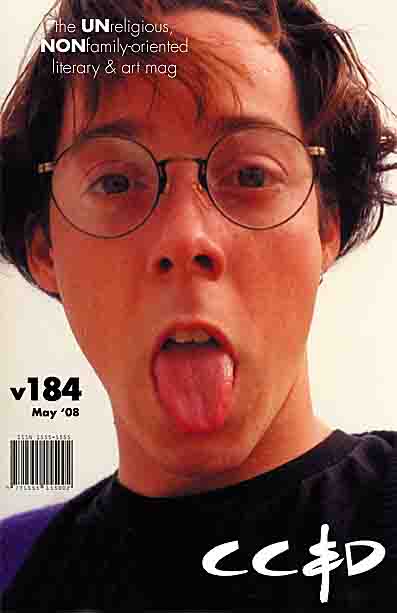

This appears in May 2008 v184 issue (saddle-stitched) of cc&d magazine. Click the issue number or the cover to see that issue online. |

|

This writing also appears in the published 100 page perfect-bound ISSN#/ISBN# issue/book “This was the Time” cc&d v184 May 2008, reprinted in 2019! (the 2019 reprinting of the May 2008, v184 issue, that also contains 3 bonus 2008 live poetry chapbooks!) Order this as a 6"x9" paperback book: |

|||||

|

| |||||||

|

Charred Remnants (b&w pgs): paperback book $18.95 (b&w pgs):hardcover book $32.95 (color pgs): paperback book $74.93 (color pgs): hardcover book $87.95 |

|

|

| |

|

This writing appears in the published 100 page perfect-bound ISSN#/ISBN# issue/book “That was the Time” cc&d v184 May 2008, reprinted in 2019! (the 2019 reprinting of the May 2008, v184 issue, also containing 3 bonus 2008 live poetry chapbooks!) Order this as a 6"x9" paperback book: |

|

|

|

| ||

|

Order this writing in the issue book Among the Debris the cc&d July-Dec. 2019 issues & chapbooks collection book |

|

get the 494 page July-Dec. 2019 cc&d magazine issue collection 6" x 9" ISBN# paperback book: |

| ||

![]()