|

Dusty Dog Reviews The whole project is hip, anti-academic, the poetry of reluctant grown-ups, picking noses in church. An enjoyable romp! Though also serious. |

|

Nick DiSpoldo, Small Press Review (on Children, Churches and Daddies, April 1997) Children, Churches and Daddies is eclectic, alive and is as contemporary as tomorrow’s news. |

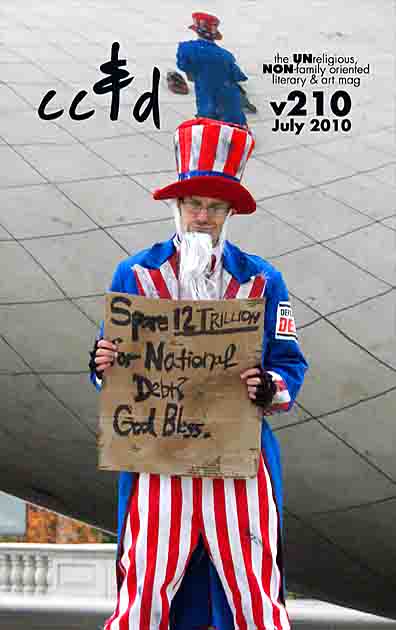

Volume 210, July 2010

The Unreligious, Non-Family-Oriented Literary and Art Magazine

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

see what’s in this issue...

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

|

Order this issue from our printer as a a paperback book (5.5" x 8.5") perfect-bound w/ b&w pages, but also released as a 6" x 9" ISSN# book Follow the link below to order the 5.5" x 8.5" ISSN# book:  Follow the link below to order the 6" x 9" ISSN# book:

|

poetry

the passionate stuff

3.4 Mantra

Charlie Newman

|

|

Charlie Newman reading his poem from cc&d magazine July 2010 (v210) Mantra 3.4 |

|

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 07/06/10 |

Self-RespectJe’free

You said you wanted breakfast,

|

food dish photographed by John Yotko

EruptionErica HegenderferI have created a hurricane to take my fury

You painted my face and called me a clown

I am no cat with numerous lives

The drop of a needle and Hate would make me a talented tailor

|

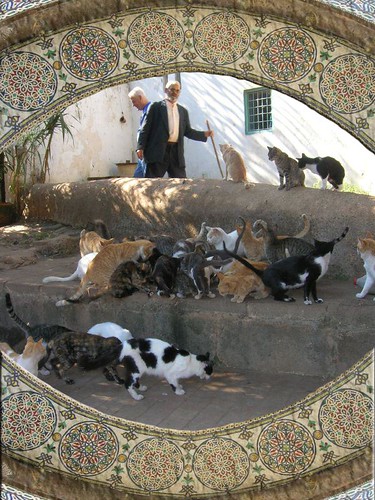

Cats Court Yard, art by Paul Baker

Cats Framed, art by Paul Baker

Probable CauseHenry Sosnowski

If you’ve had

If you’ve had

|

Scream-Sample, art by Tray Drumhann

Late Night Domino TheoryCEE

Maybe the girl lost in the woods

Now, quit arguing with me

|

wood grain, art by Tracy M. Rogers

Tracy M. Rogers BiographyTracy M. Rogers, Editor and Creative Architect for The Aurora Review: An Eclectic Literary and Cultural Magazine, is a photographer, writer, and web designer. She grew up in Fayetteville, a college town in northwestern Arkansas. She holds a history degree from the University of Arkansas and dropped out of graduate school due to “creative differences” with her faculty advisors. Her poetry can be found in Poetry Kit Magazine and the current issue of Prism Quarterly. When she is not masterminding The Aurora Review, Tracy is either busy writing her first novel or working on her ongoing “Clouds” photo project.

|

The Kitchen ManagerMatthew Czerwinski

I’ve just started working

“Hey Don get that order moving.

‘never trust a guy with a white name.’”

He laughs at his own joke.

knows it well. He knows the poetry

I end the night soaked, grease-stained,

He can mince a pile of cilantro

But just like I don’t tell him, he will not

|

Jack in the Box, art by Christine Sorich

Deep ThroatMichael Ceraolo

Strange

Felt had worked (wormed?) his way up the hierarchy,

Hoover dies

The web version of this poem does not have Michael Ceraolo’s indentations. |

Stand Proud, art by Mark Graham

Just for funkaliforniai reside within you i’ll eat your insides then jump out and skin you make a jacket with your flesh go in your fridge and grab a frash beer and watch tv throw your remains in the ivy take your car and go to the store grab a whore and bring her back to your place fuck her to death then rip off her face and make a mask and dance around like a satanic clown smash pictures of your family and slash myself with the glass i have mass appeal in hell they love me they wanna shove me in a blender and all take a drink i wanna run your family van off the road and watch you all sink in the lake screamin fuckin cryin i’m laughin while you’re dyin no fuckin ryme no fuckin reason i just like to hunt and humans are always in season

|

The Optimism ofthe Criminal MindColin James

The gun had symptoms

|

|

Janet Kuypers reading a poem by Colin James from cc&d magazine July 2010 (v210) the Optimism of the Criminal Mind |

|

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 07/06/10 |

53 ChevyMike Berger, PhD

People laugh at my old beater car.

I don’t care for the glitz, that’s not what

|

art by David J. Thompson

When Daddy Comes AroundJulie Kovacs

He is never around

|

About Julie KovacsJulie Kovacs lives in Venice, Florida. Her poetry has been published in Children Churches and Daddies, Because We Write, Illogical Muse, Poems Niederngasse, Aquapolis, The Blotter, and Cherry Bleeds. She is the author of two poetry books: Silver Moonbeams, and The Emerald Grail. Her website is at http://thebiographicalpoet.blogspot.com/

|

|

Janet Kuypers reading a poem by Julie Kovacs from cc&d magazine July 2010 (v210) When Daddy Comes Around |

|

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 07/20/10 |

cartoon by David Sowards

performance art

Janet Kuypers 06/22/10 live

Chicago poetry, prose & music feature

too farWhen he met mehe told me I looked like Kim Basinger long blonde locks but as time wore on I knew I wasn’t her and I could never be her and I was never good enough thin enough pretty enough I got a perm straightened my teeth bought a wonder bra but it wasn’t doing the trick I bought slimfast used the stair stepper ate rice cakes and wheat germ but I wasn’t thin enough I only dropped twenty pounds so I went to the spa got my skin peeled soaked myself in mud wrapped myself in cellophane bought the amino acid facial creams but I knew they didn’t really work so I went to the doctor got my nose slimmed my tummy stapled my thighs sucked

thought about

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Too Far |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

The Apartment“Could you pull out a can of sardines to have with lunch?”, he asked me, so I got up from my chair, put down the financial pages, and walked into the kitchen. The newspaper fell to the ground, falling out of order. I stepped on the pages as I walked away. I realized he hadn’t been listening to a thing I said. He had to look for a job, I had told him before. This apartment is too small and we still can’t afford it. I put in so many extra hours at work, and he doesn’t even help at home. There are dishes left from last week. There is spaghetti sauce crusted on one of the plates in the sink. I opened up the pantry, moved the cans of string beans and cream corn. There was an old can of peaches in the back; I didn’t even know it was there. I found a sardine can in the back of the shelf. I saw him from across the apartment as I opened up the can. “We have to do something about this,” I said. “I can’t even think in this place. I’m tired of living in a cubicle.” He closed the funny pages. “Get used to it, honey. This is all we’ll ever get. You think you’ll get better? You think you deserve it? For some people, this is all they’ll get. That’s just the way life is.” I looked at the can. I looked at the little creatures crammed into their little pattern. It almost looked like they were supposed to be that way, like they were created to be put into a can. The smell made me dizzy. I pushed the can away from me. I couldn’t look at it any longer. This writing appears in the books Hope Chest in the Attic, (woman.), and Exaro Versus. |

| the Janet Kuypers short prose / flash fiction the Apartment (with John Yotko male vocals) |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

leaving

She walked over to the thermostat again.

“Could you get a can of sardines while

She walked a mile and a half in the cold

She walked to the center of the field.

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Leaving (with John Yotko male vocals) |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

|

This writing appears in the books Close Cover Before Striking, Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite and Wake-Up Call from Tradition, and it also appeared in the collection book Weathered. |

A Socially Accepted Targetrape is connectedto the frustration produced by living in this society

rape is anger

i didn’t get the promotion i deserved

this traffic is always in my way i’m angry all the time

and the damn kids are banging i just want a fucking beer, you bitch it’s all your fault

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem A Socially Accepted Target with C Ra McGuirt video and vocals |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

for better or for worsefor better or for worsebut all you’re offering me is worse & I just can’t see it getting better

|

| the Janet Kuypers twitter-length poem for Better or for Worse |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Most Accurate Metaphorsrape is one of the most savageone of the most accurate metaphors for how men relate to women in this society

it is a political crime

rape is an attempt by men Bob Lamm, 1976

now there’s two ways

you know you want this

i saw the way you were

did you think those drinks

how long did you think

just do as i say

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Most Accurate Metaphors with C Ra McGuirt video and vocals |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

i’m really going this time

i pack my bags

you throw my bags

before you get more violent

i’m sitting in my car

see you at the window

why do i have to think

why do i come back,

what you’ve done to me,

you’re about to lose.

you’ll call me once

forgotten. other times,

i’ve come back. but i

to the ground, strangled.

lost that night, i’m

remember that you

i’m really going this time,

carry this with you,

the pain you’ve given me.

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem I’m Really Going This Time |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

| This writing appears in the books Close Cover Before Striking, and (woman.). |

precinct fourteenit was a long night for us, starting outat your apartment with your roommate’s coworkers coming over and making

margaritas until two in the morning,

and so off to the blue note we went,

first time i ever did that, closed a late-

and i know it angles, and you can see

but i’m sure the light was green, and not

trouble that night, no insurance, no city

over a year now, a cracked windshield,

and all they did was write you a ticket,

you drove me home, and the cops met

was a lot of fun, even with the involvement

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Precinct Fourteen |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

| This writing appears in the books Contents Under Pressure and Oeuvre. |

Losswalked with you in an ALS rallyafter I had locked my keys in my car

saw you a few times

you looked fine I couldn’t see anything wrong with you *

finally, I would call you

and I invited you to visit me

and you would say, why

I didn’t want this to happen to you,

your family watch lupis take a loved one

your mind is just fine

it’s just that your nervous system

and your crystal clear, sharp mind

I know this is rare

and watching you go through this

as you live through your days now

like the flapping of hummingbird wings

I know I’m not the one suffering *

I know I’ve lived through hell just to watch this happen to you *

went to a funeral today

wheelchair bound, slurred speech

but still smiling when you saw me

with you, who could barely speak

your friend held your cigarette outside with you

so you could inhale, then he pulled it away *

I couldn’t stay at the funeral too long

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Loss |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

my love for you |

| the Janet Kuypers / MFV song My Love For You Will Stay the Same |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the “extract” filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the “find edges” filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with an metallic filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (w/ “Blue Screen Key”) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (w/ “old film” & “page curl”) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the “pastel sketch” filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the solarize filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

|

This writing appears in the books The Window, Sing Your Life, and Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite. |

Keep Them Apartthey say headlights run in parallel linesthe never touch but you know, when humans try to recreate science they never get it right and i don’t care how many miles it takes i don’t care how long it takes but eventually they will touch they will cross they will intermingle for one brief moment

you think they’re meant to stay apart

but they’ll come together

it doesn’t matter where that car is traveling

even if it’s only to cross each other

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Keep Them Apart |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Only For One NightI had left everythingand I stumbled upon you

I didn’t know what I was looking for

you had the same anger in you as I

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Only For One Night |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Got on the Road AgainI slept in my carwaiting to see you

after scrubbing my clothes

when I was with you,

and it was harmonizing

but I had to pack up again

|

| the Janet Kuypers poem Got on the Road Again |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

what we need in life(a song)

I don’t know where this highway’s taking me anymore and

nothing ventured

but you go your way what we need in life what we need in life

I watch the ashes from your cigarette

nothing ventured

so you go your way what we need in life what we need in life

I can’t stay bitter and lonely and restless anymore and

nothing ventured

you go your way what we need in life what we need in life

|

| the Janet Kuypers / MFV song What We Need In Life |

Watch this YouTube video live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

|

Watch this YouTube video (with the solarize filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

|

Watch this YouTube video (w/ extract/page curl filters) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the “find edges” filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (w/ an metallic/page curl filters) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (w/ Blue Screen Key) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (w/ old film/page curl filters) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

Watch this YouTube video (with the “pastel sketch” filter) live at the Café in Chicago 06/22/10 |

|

This writing appears in the books Close Cover Before Striking, Sing Your Life, Chapter 38 v1 and Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite. This song was original performed by Mom’s Favorite Vase (music by Warren Peterson) at bars in Chicago (inclding a venue with Poi Dog Pondering for a political event and a concert where the Grateful Dead tribute band Uncle John’s Band opened for Mom’s Favorite Vase), but this song has been performed this millennium (with John Yotko) live in Chicago, Tennessee, Alaska, and over the Pacific Ocean to audience members from the United States, Canada, Ecuador and Austria. |

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

The Long Road HomeValor Brown

This drive is different than other drives. Normally I might be looking at the saguaro cacti or the vast, arid and strangely refreshing beauty of the desert. This drive is over an hour when speeding and there is usually a balance of peace and urgency due to the monotony. One straight line, while on both sides escorted by purple mountain tops. Tempting and unattainable they seem, for they are far from this flat landscape; even more so knowing I don’t won’t be looking at them again. At least I have the breeze of a moving vehicle. My palms are sweating and my heart is spasming uncontrollably it seems. If I dared to look at my chest, I might see it like never before amid its desperation. I don’t.

|

Rage Militia, art by Aaron Wilder

Tube TravelMike Wilson

They came for him early that morning. Not even allowing him to eat breakfast, they slapped some handcuffs on him and said, “This is your day. If you live through it, you get to go free.”

“But we need to do some of this right away, while your memory is still fresh. Now, please, Mark.”

Mark Maulsby was walking down Main street on a sunlit morning. He was free now, and feeling full of love, and in love with life. He loved every ounce of the world, every dirty cigarette butt on the ground, every soiled park bench, every grimy bus sign, every stumbling, slobbering homeless drunk. He still had some cash from the modest amount given to him by the correctional facility upon his discharge. As another panhandler approached him, noting how he had handed out some bills already, he gave the man a big smile. “Do you need help, sir? I want to make a difference in this big, beautiful world.” And handed him one of his last dollar bills.

He didn’t get a chance to finish. Dennis produced a 12-inch long hunting knife, and plunged it into Mark’s side one, two, three times. Mark gasped in pain and surprise, his hands trying to block the knife and getting cut in the process.

Dr. Sanderson sat stunned in a break room at the institute, watching the news report with several other doctors and aides. “Mark Maulsby, a former inmate who recently took part in a groundbreaking experiment in long distance travel, was found stabbed to death on a bus bench in central ......”

“The fact of Mark Maulsby’s transformation from a hardened convict to a charitable person is something that requires further study. The fiber-optic transport system that we thought would revolutionize travel now seems to have an additional benefit. It seems that during Maulsby’s transit and reassembly, the computer programs that reassembled him made some automatic adjustments to his brain.” Drs Sanderson and Kagin were lecturing an assembled group of specialists at an institute office in Los Angeles.

Dr. Kagin thought to himself, you just can’t help it, you old fool. Always having to be the adventurer.

“Are you sure you won’t stay a little while longer, Doctor?” Dr. Sanderson looked at Kagin, concerned.

The meeting room had built up an aura of tension almost as thick as the odors of sweat and stale coffee.

Renie Abelson stared at the strange apparatus facing him. What he saw were hundreds of protrusions all around his ‘chair’ and facing him was a small glass tube about 1 inch in diameter. They told him he was going to be sent through that? <>IMaybe this will be my execution, they just didn’t want to tell me outright. Well, no turning back now. I signed all the papers. If I make it, I get to go free - a commutation by the Governor himself.

They sent more inmates through. The results were mostly what they had hoped. The meaner, more vicious death-row inmates came out the kindest, sweetest people one could hope for. But the last one, who was merely a convicted small-time drug dealer, came out the least changed. He was still a bit worldly. And he was showing some ill aftereffects.

Meanwhile, Dr. Kagin was enjoying the sights, sounds and smells of Portland street life. He had been patient, biding his time, selecting a victim carefully. We didn’t get to use a knife like this in med school. But then I never got to do an autopsy on a live person before. He could already smell the blood, hear the screams, and this gave him an erection. His intended victim, a small girl, ran and skipped away down a street. He followed from a distance, figuring out the best place to do his thing.

Dr. Sanderson waved a copy of the LA Times at the assembled board of the Institute, in consternation.

Dr. Kagin sat in the busy police precinct office, gazing around. An officer finished typing his report, turned to him and said, “one of your colleagues is coming down to pick you up.”

|

KeltonBillie Louise Jones

Kelton House was a home for old folks who needed watching over. On a quiet, leafy old street in Hot Springs, Arkansas, it was a turn of the century house, white with green shutters and shingles, a wrap around porch, a side wing that had been a conservatory and ball room, and ramps convenient to walkers and canes.

|

Iron Steps, art by Cheryl Townsend

The Girl who Pulled Down the SunKevin Phillips

Soft as a snowflake

Once upon a—

Once upon a tower there was a girl who pulled down the sun.

She was born backwards and upside down. I know, for I was there. It was a cold winter’s day, and all the men were at work. Lydia Shepaug, my mother, lay beside the fire, panting her prayers up the chimney. The midwives were tending to others, and I, well, I was a boy. What good was I?

The day after, the sun once again retreated to the top of the sky and turned away, ashamed of what it had done. My mother, in the cold shadows of the front porch, accepted her child to bosom for the first time. Revolted at first to clasp such a strange, otherworldly face to her breast, she was still a mother, and her instincts were strong. For our parts, feeding time was the best time of the day. It was when my sister buried herself in my mother’s blouses. It was when she was hidden. It was when we could almost forget.

You want a confession? Here’s one: I loved my sister. It didn’t matter what Agnes Wilton said, it didn’t matter that, in her eyes, Ellie was a freak. She was my sister. She was my blood.

Perhaps you are wondering where God was in all this, why He didn’t pull the sun down himself.

We stored her in the silo after that.

But I had no power, at least not yet, and Rumor was a hawk.

“Stay away from those men,” I told her one evening as she braided her hair out the window. By then I thought I knew what men like these could do.

A week later the town commissioned The Tower. It was an audacious project, an odd project, since most of the building I had ever seen went into the earth, not above it. We were miners. What did we know about towers?

Weeks passed, months, during which the Tower slowly rose, in beams and scaffolds, into the pale blue sky. Maybe someday, I thought, it would stand higher than the sun itself. Maybe Ellie would sit above it in the end.

Soon enough, the men came. Young men, old men, married men, the men of town, the men of the mines.

Agnes Wilton, however, saw the Devil in Ellie’s teeth. Not only had the old woman’s brothers abandoned her for beauty, but so too had her husband, the Boss. When he wasn’t supervising The Tower site, he was standing beneath Ellie’s window reciting poetry he’d written for her himself.

I had achieved one concession, although in doing so I condemned my sister to further humiliation. I convinced the council to let Ellie choose her punishment freely. Given the choice, she would climb, I knew, and she wouldn’t need the town at her back. She deserved to leave this world as she entered it, I told them—bathed in light and full of wonder.

I hope you’ll forgive me—

Naked as I instructed her, Ellie climbed to the top of Roxbury Hill. Hidden behind rocks and machines were the men of town, but they dared not stir. She was timid as a deer, or so they thought, and their darting eyes might scare her away.

Roxbury Hill changed almost overnight. With each touch of skin it grew softer. Worms and roots spiraled up out of the earth, on the scent trail of death, only to find life waiting for them on the surface. No bodies to take back with them. None of God’s stricken. So they returned to the dark, unwanted and unfulfilled. But their work was done. In their rummaging wake they had left rocks broken, the clay split, and all the hard earth turned.

I’m an old man and I’m tired. We’ll save Agnes for another day. Now, if you’ll excuse me. There’s nothing left to tell.

The old man pushed his way through the forest, a smile upon his lips. Finally. He was finally finishing what he had started seventy years ago.

|

BeastsAlison Balaskovits

Gran-ma-ma would fill my head with any number of tales, each one similar to the one that came before: the hapless heroine, played by yours truly, would end up the glorified meal to some toothy, touchy beast.

|

Creepy Uncle Is Watching YouBrian Haycock

Welcome to the not-so-brave new world. Don’t get too comfortable. Try not to relax.

|

BioBrian Haycock lives in Austin, Texas, where he has worked mainly for nonprofit organizations. He enjoys running (especially in the summer heat), hiking and reading stories of all kinds. His stories have appeared in Thuglit, Nefarious, Yellow Mama, Amarillo Bay, Crime and Suspense, Reflection’s Edge, Darkest Before the Dawn, Pulp Pusher, Swill, and other highly respectable publications. His book about modern Zen practice, Dharma Road, will be published in Fall 2010 by Hampton Roads Publishing. Check him out at brianhaycock.blogspot.com/. Unlike the people he writes about, he is law-abiding and reasonably sane. Really.

|

Telemundo Telecast, art by Nick Brazinsky

The PerformerBob Rashkow

He’d been job hunting all afternoon and had finally scored a point. The elderly woman at the YMCA on 87th and Roosevelt had taken his application, asked him only a few additional questions, and promised that someone in administration would call him back—about working the front desk evenings for 8 dollars an hour, 26 hours a week. Well, it was something; it would help pay his bills and his food. Now he was trying to relax. The Junction Boulevard bus wended its way south toward home. Crowds of passengers got on at every stop or got off. It was getting close to rush hour, maybe 4:30 or so. He sat way in the back of the bus, the classifieds tucked neatly under his arm, and almost started to doze. At Corona Avenue, a huge black woman dangling two shopping bags filled to the rim insinuated herself next to him, coming within inches of crushing his hand. He barely looked up.

|

Sing Out, painting by Jay Marvin

She Dances, art by Edward Michael O’Durr Supranowicz

DTF Bangin Hot 01, art by David Matson

Fake It ‘Til You Make ItJess DunnRachel is a girl. She collects shiny rocks. She spends hours listening to raindrops collect in jars on her window ledge. The rain falls through the open window, landing on her face and arms, but she does not care. Rachel lies on her back and watches the ceiling fan go around and around until all the blades blur together. She does not smile like other children. When she laughs, the sound she makes is flat. If they touch her, she screams and bangs her head on the floor until she loses consciousness. That is because Rachel is crazy.

I look down at my stomach. It is round and hard, like a melon. I move my head closer to it and rap it with three fingers like old ladies do with cantaloupe in the grocery store. Once, one of the ladies told me that if you heard a hollow sound that meant it was ripe. I listen to see if my stomach makes a hollow sound. A few minutes later, there is a tap from the inside and I wonder if the thing within is listening to see if the world makes a hollow sound.

Rachel will not put her feces in the toilet. She hides them in the bottom of her toy chest. Even when they make her use the toilet, she will not flush it. She just stares down at the pieces of her floating outside. When they tell her to flush it, she ignores them. When they flush it for her, she hits them and they hold her down and let her scream until she can not make another sound. That is because Rachel never lets anything that was inside her go so far away.

Sharon tells me that cutting it out will leave a scar. She says that natural childbirth is best. Sharon works in the library and so do I. She talks to me because I am very quiet and she believes this means that I am a good listener. Sharon asks me if I know who the father is. I say that I know who made me pregnant. I say pregnant because I know that is what you are supposed to say when you have a thing in your uterus and that thing is not a tumor.

Rachel is eight years old. She can multiply numbers like 3,598 by 1,569 in her head. She can remember a random string of up to twenty-five digits after seeing it written once. These are games that she likes to play. When others hear her games, they make her take tests for hours. Some of the tests are puzzles, which are fun, but most of the tests are pictures that you have to make into stories. These tests make Rachel angry because stories are not pictures and making things into something they are not is not fun. If she does not finish the tests, they make her talk to strangers, as many as three at a time. When the strangers talk to her, she hums until she can not hear them anymore. Eventually, she stops playing her games and, eventually, they stop testing her. That is because Rachel can play their game.

Sharon says “Rachel, having a baby is the most wonderful experience” and I nod because do not want to talk about my uterus anymore. But if I say this, she will ask me a question and then I will have to answer the question or she will ask me why I do not want to answer the question...ad infinitum, which means ‘unto infinity.’ Sharon continues, because she thinks that when I nod, it is an invitation to continue and not an invitation to go away. This is why I do not like gestures; because they are ambiguous, like the picture of a white vase on a black background that is also two faces in profile. If I try to see both pictures at once, I get a headache, and it is the same with gestures.

Rachel lies on her back in the room with the couch and watches the ceiling fan. Sometimes she holds her hand, fingers splayed, above her eyes and moves it back and forth, slowly at first, and then faster and faster. The pattern of light and shadow makes her calm. This is because when she is looking at the pattern, nothing else can get in and she is alone, even when there are people around. When someone else is in the room with the couch, they stand over her, so that she can not see the fan. She continues to move her fingers back and forth, but the pattern is not the same. They tell her to look them in the eyes.

Seven months ago, a man who used to come to the library every day asked to take me home after work. I live in an apartment on the fifth floor of an eight story building. I walk up sixty-five steps to get to my floor. I do not take the elevator because it always smells like a crowd of sweaty people, even when there is no one inside. My apartment has four small rooms: a bathroom, a living room, a kitchen and a bedroom. The bedroom has a ceiling fan with an attached light and my bed is right underneath it. There are two switches next to the door, one for the fan and one for the light. I never use the fan switch.

Rachel screams when anyone touches her and bangs her head against the floor. When they ask her why she does this, she tells them that it hurts. They tell her that being touched does not hurt, unless someone touches too hard. She tells them that it is always too hard and they tell her that she is wrong. They take her into a padded room and someone touches her on the arm to show that it does not hurt.

Sharon tells me that the thing inside me is a piece of me to send out into the world. When you cut an apple into pieces, the pieces are still apple. If I cut a part of myself out, the part is still me. I do not want to flush me out into the world so far away. Sharon keeps talking about pieces of us in the world and I begin to hum so that I can not hear her. She stops and asks me if I am upset; when I keep humming, she reaches out and touches my hand. I want to scream, but screaming is like a gesture and some people think it means you want a lot of them to crowd around you. Instead I stay very still and quiet until she stops. I say that I am sick and need to go home. I say this, because that is how you are supposed to ask to be left alone, even though it is not a question.

Rachel is in the hospital and she has been there for years. They say that she is sick, even though she does not feel sick. They will let her leave when she is better. They believe that she is sick because of the ceiling fans and games and wanting to be left alone. Rachel does not understand this because those things make her feel good and being sick is supposed to feel bad. She stops doing those things, anyway. They believe that if she looks at other people in the eyes and talks to them and plays their games that she will be better. Rachel does not understand this, because those things make her feel bad and being well is supposed to feel good. She starts doing those things anyway. That is because Rachel can fake it.

I am in the hospital and I am not sick. It is time for the thing to come out. The nurse in the doctor’s office asks if I am sure that I want a caesarian section. I say that I want Rachel to be cut out, which is what caesarian section means. The nurse smiles and asks me if I know that it will be a girl and I nod. I do not know that the thing will be a girl, but I do know that it will be me. I nod because I know that saying that the thing inside you is you is a strange thing to say.

We are a woman and a very small girl. We collect shiny rocks. We spend hours listening to raindrops collect in jars on the window ledge. The rain falls through the open window on our arms and face, but we do not care. Sometimes, we lie on the bed together and watch the ceiling fan go around and around until all the blades blur together. We do not smile like other people. When we laugh, we do not mimic anyone and the sound we make is flat. If anyone touches us, we will scream and bang our heads against the floor. That is because we are Rachel.

|

the World is my Embrio, art by the HA!man of South Africa

Old Man Brier MoranSkibo LeBlanc

They still speak of Old Man Brier Moran. They tell tales of his feats in their cozy confines during the night, and sing songs of his legend out in the Field during the day. Parents tell their children bedtime stories of his exploits and, at the end of these yarns, the same children pray for his protection, their own visions of the man dancing around in their tiny minds. They have never known the truth of the circumstances behind his legend, however, and their ignorance continues to this day. He is their hero “now and has always been” they say, but time twists memories, and in reality, ‘twas not always so.

I lived in the House for many years, never finding the motive within to leave, but telling the people about that night, and always hiding my mark. I told whoever cared to know, how the “home” had been attacked by the evil Red Men, and how Brier had smote them down, saving all of us within, at the cost of his own life. I spoke of witnessing him rise into the sky after his death, the ascent of a holy being. He had been one of them and I thought they should care.

|

Interview

Susquehanna University

|

Debra Purdy Kong, writer, British Columbia, Canada I like the magazine a lot. I like the spacious lay-out and the different coloured pages and the variety of writer’s styles. Too many literary magazines read as if everyone graduated from the same course. We need to collect more voices like these and send them everywhere.

Children, Churches and Daddies. It speaks for itself. Write to Scars Publications to submit poetry, prose and artwork to Children, Churches and Daddies literary magazine, or to inquire about having your own chapbook, and maybe a few reviews like these.

what is veganism? A vegan (VEE-gun) is someone who does not consume any animal products. While vegetarians avoid flesh foods, vegans don’t consume dairy or egg products, as well as animal products in clothing and other sources. why veganism? This cruelty-free lifestyle provides many benefits, to animals, the environment and to ourselves. The meat and dairy industry abuses billions of animals. Animal agriculture takes an enormous toll on the land. Consumtion of animal products has been linked to heart disease, colon and breast cancer, osteoporosis, diabetes and a host of other conditions. so what is vegan action?

We can succeed in shifting agriculture away from factory farming, saving millions, or even billions of chickens, cows, pigs, sheep turkeys and other animals from cruelty. A vegan, cruelty-free lifestyle may be the most important step a person can take towards creatin a more just and compassionate society. Contact us for membership information, t-shirt sales or donations.

vegan action

Children, Churches and Daddies no longer distributes free contributor’s copies of issues. In order to receive issues of Children, Churches and Daddies, contact Janet Kuypers at the cc&d e-mail addres. Free electronic subscriptions are available via email. All you need to do is email ccandd@scars.tv... and ask to be added to the free cc+d electronic subscription mailing list. And you can still see issues every month at the Children, Churches and Daddies website, located at http://scars.tv

MIT Vegetarian Support Group (VSG)

functions: We also have a discussion group for all issues related to vegetarianism, which currently has about 150 members, many of whom are outside the Boston area. The group is focusing more toward outreach and evolving from what it has been in years past. We welcome new members, as well as the opportunity to inform people about the benefits of vegetarianism, to our health, the environment, animal welfare, and a variety of other issues.

Dusty Dog Reviews: These poems document a very complicated internal response to the feminine side of social existence. And as the book proceeds the poems become increasingly psychologically complex and, ultimately, fascinating and genuinely rewarding.

Dusty Dog Reviews: She opens with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, CA Indeed, there’s a healthy balance here between wit and dark vision, romance and reality, just as there’s a good balance between words and graphics. The work shows brave self-exploration, and serves as a reminder of mortality and the fragile beauty of friendship.

Mark Blickley, writer You Have to be Published to be Appreciated. Do you want to be heard? Contact Children, Churches and Daddies about book or chapbook publishing. These reviews can be yours. Scars Publications, attention J. Kuypers. We’re only an e-mail away. Write to us.

The Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology The Solar Energy Research & Education Foundation (SEREF), a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C., established on Earth Day 1993 the Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology (CREST) as its central project. CREST’s three principal projects are to provide: * on-site training and education workshops on the sustainable development interconnections of energy, economics and environment; * on-line distance learning/training resources on CREST’s SOLSTICE computer, available from 144 countries through email and the Internet; * on-disc training and educational resources through the use of interactive multimedia applications on CD-ROM computer discs - showcasing current achievements and future opportunities in sustainable energy development. The CREST staff also does “on the road” presentations, demonstrations, and workshops showcasing its activities and available resources. For More Information Please Contact: Deborah Anderson dja@crest.org or (202) 289-0061

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA want a review like this? contact scars about getting your own book published.

The magazine Children Churches and Daddies is Copyright © 1993 through 2010 Scars Publications and Design. The rights of the individual pieces remain with the authors. No material may be reprinted without express permission from the author.

Okay, nilla wafer. Listen up and listen good. How to save your life. Submit, or I’ll have to kill you.

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA: “Hope Chest in the Attic” captures the complexity of human nature and reveals startling yet profound discernments about the travesties that surge through the course of life. This collection of poetry, prose and artwork reflects sensitivity toward feminist issues concerning abuse, sexism and equality. It also probes the emotional torrent that people may experience as a reaction to the delicate topics of death, love and family. “Chain Smoking” depicts the emotional distress that afflicted a friend while he struggled to clarify his sexual ambiguity. Not only does this thought-provoking profile address the plight that homosexuals face in a homophobic society, it also characterizes the essence of friendship. “The room of the rape” is a passionate representation of the suffering rape victims experience. Vivid descriptions, rich symbolism, and candid expressions paint a shocking portrait of victory over the gripping fear that consumes the soul after a painful exploitation.

Dusty Dog Reviews (on Without You): She open with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

|