Rhetoric and the Written Word

cc&d magazine

v267, January 2017

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

poetry

the passionate stuff

|

stuck

Patrick fealey

it’s Sunday

my head hurts

I have to review

A book

Before I review it

I have to read it

It’s Sunday

My head hurts

I might feel better

If I could write

My own thoughts

But I have to review

This book

I’ve read 14 pages

And it sucks

Like no toilet paper

It sucks like turbulence at 30K feet

It sucks like finding your car

Has been towed

It sucks so bad

I can hear the trees mourn

But I have to review

This book

It’d been published

By nepotism

And so I am required to review it

I guess I should go now

And read it

If I lie

And say some good things

There’s a chance the publisher

Will look at my work

The words I don’t have time

To write

But I won’t do that

Because whoever published this

Sucks shit out of the brown eye

I will read it and it will suck

I will worsen my headache

Carefully writing a negative review

Without saying

Anything negative

Like it sucks

And the publisher will complain

And the writer may complain

And my editor

The author’s friend

Will pay me

And more books

Will arrive

In Monday’s mail

|

rabble

Patrick Fealey

the edges of our dreams if we had them are worn smooth as the cobblestones at our stinking feet, flat as our asses on the only bench they gave us . . . here comes a green jaguar, british racing green, to adjust my perceived material security: got $4 in my wallet, half a pack of camels, and eight rolling rocks in the tiny fridge . . . tomorrow's hustle is distant and i am lifted strong by the morphine pulsing through my head. i live in a cell upstairs so they think they can give me their diseases. they strangle one another and the cops interrogate me; they think i am one of them. i have fallen and they have never imagined a phoenix boy. to them, i am never getting out of here because nobody does. i am one of them. they see me at the soup kitchen with my mouth shut. they believe my stupidity brought me to the world they own. i am less than one of them. they beat one another with hammers and overdose and rot like any old liars . . . the jaguar eases down farewell street . . . tomorrow's suicide asks me for a cigarette. i say yes.

|

Prescription

Patrick Fealey

My back’s against a brick wall, a camel warming my head as i listen to the buzz of locusts flooding the lot with copper light. a plague of light. inside, they’re cooking up my salvation, a these and those cocktail stronger than any doctor ever saw. a moth flies past with the history of my life written on one wing, the other wing lucid as skin. he is moving too fast, but i catch the drift. there was a time when a thing i mistook for courage flickered before my eyes like a bug caught in a wine glass. i don’t know anything anymore. i can’t find a cause but silence, stillness, ears and ears. the brick wall is cool, my back aches. the nicotine finds the channels. a pizza delivery car goes by. i haven’t eaten. i will not eat. i have to go now, stepping on a butt and into the greeting card brightness. my surrender is prepared.

|

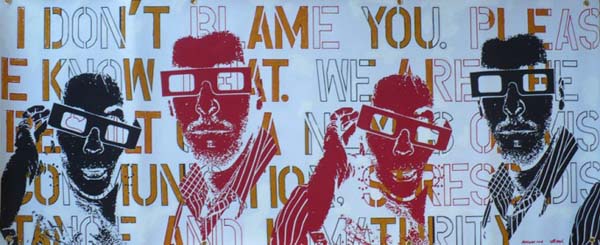

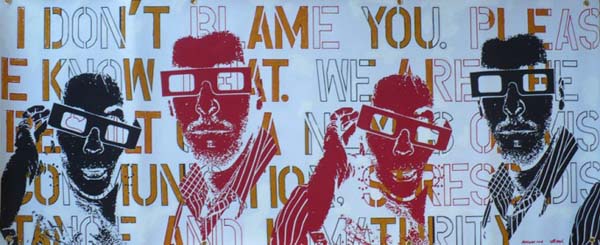

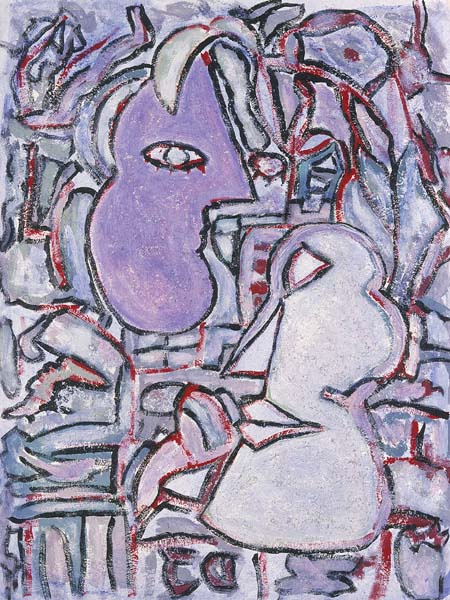

Elephantine Curioso, art by Brian Looney

Medication

Janet Kuypers

spring 1992

I

I set my alarm for 4:30 instead of 5:30 so I could

roll over, take a pill, and fall back asleep. I’d leave two pills on the

night stand with a glass of water every night. I could feel the pain

in my leg, my hand, when I reached over to take the drugs. I’d

feel it in my back, too. And sometimes in my shoulder. The

water always tasted warm and dusty. It hurt to hold the pills

in my right hand.

I closed my eyes at 4:32. I hated that damn alarm clock. And

taking the pills early still wouldn’t make the pain go away

before I woke up. I knew that. But I took them anyway. And

I tried to fall back asleep. And I dreaded 5:30, when I’d have to move.

5:40, I couldn’t wait any longer, I couldn’t be late, we

couldn’t have that, so I’d finally swing my legs to the floor.

I’d put on my robe and limp into the kitchen. The trip to the

kitchen lasted for hours. And picking up the milk carton from the

refrigerator hurt like hell. This wasn’t supposed to be happening,

not to me. Just pour the damn milk. I’d wipe the tears from my chin

and sit down for breakfast.

II

The doctor doubled the dosage, and he was amazed

that I needed this much. He told me to follow the directions

strictly, STRICTLY. “You can’t take these in the morning the way

you have been,” he’d say. “You have to take them with food.”

That doesn’t help when I’m crying from the pain in the morning.

But I could get an ulcer, he’d say. And I wouldn’t want that.

Of course not. I just wanted the pain to go away.

Take one tablet three times daily, with meals.

Do not drink alcohol while on medication.

Take with food or milk. Do not skip medication.

Do not take aspirin while using this product.

Do not operate heavy machinery. May cause ulcers.

III

All I had to do was get through the mornings. The mornings

were the hardest part. Just take a little more pain, and

by the afternoon it will all be fine. Just fine.

An hour after the pills, and I’d start to feel dizzy.

I’d stare at a computer screen and it would move, in circles, back and

forth. I wanted to grab the screen and make it stay in place. But

I’d look at my fingers and they would go in and out

of focus. I’d feel my head rocking forward and backward;

I couldn’t hold myself still. I’d sit at my desk and my eyes would

open and close, open and close. Before I knew it, ten minutes passed

and I remembered nothing. I could have been screaming

for ten minutes straight and I wouldn’t have known it. Or crying.

Or sleeping. Or laughing. Or dying.

I had just lost ten minutes of my life, they were just taken

away from me, ripped away from me, and I could never

get them back.

And I could still feel traces of the pain, lingering in my bones.

IV

I’d sit up at night and just stare at the bottle. It was a

big bottle, as if the doctors knew I’d take these drugs forever.

Hadn’t it been forever already? I’d open a bottle, look at a pill.

They looked big too. Pink and white. What pretty colors.

And then I’d think: If one tablet, fifty milligrams, could put me

to sleep in the morning, could make me dizzy, could take

a part of my life from me, then think about what the other

thirty-six could do. 1800 milligrams. It could kill me.

I wouldn’t want that. Of course not.

But just think, the bottle isn’t even full.

May cause ulcers. May cause dizziness. Side effects may vary

for each patient. May cause weight gain. May cause weight loss.

May cause drowsiness. May cause irritability.

Medication may have to be taken consistently

for weeks before expected results. If effects become severe,

consult physician immediately.

V

I began to count. In the mornings I took eight pills:

one multivitamin, one calcium pill, one niacin pill, one

fish oil capsule, one garlic oil pill, and one pink-and-white

pain killer that I was special to have, because you need

a doctor’s permission to take those. Then I took diet pills:

one starch blocker, one that was called a “fat magnet.”

As if the diet pills worked anyway. But I still took them.

And then I had to watch the clock, take a pink-and-white

at one in the afternoon, a different pill at five o’clock,

another pink-and-white at six o’clock, and there was also

usually sinus medication that I had to take every

six hours in there, too. Or was it eight hours? I started to

watch the clock all the time, I bought a pill container

for my purse so that I would always have my medication with me.

When I’d feel my body start to ache again, I’d look at the clock.

It would be fifteen minutes before I had to take another pill.

|

Inside America’s Studio:

What Sound or Noise Do You Hate?

CEE

Stumped by the shock

Of persons learning of persons

Hurt and harmed for protesting,

Most people, of course,

Don’t know how to protest

They do it lone wolf

(or Cap with sucker-Bucky friend)

In a kind of

“if no guns, we’re not vigilantes

so, it shouldn’t count”

Protest, in our Brave New Edward Munch

Is one or two or the Bombastic Four

Doing the shit Cheech-class in

Sister Mary Elephant

In our “Shut Up ad Sit Down”-nation

I always speak of with—yes—disdain,

Whatever candidate or Amy Schumer

The summer school gang’s gonna

Ambush Ye,

Why are persons shocked

By persons hating and beating

Persons?

Cain set precedent

And cops are tired the of 52-Pick Up

Of going to jail

|

Home Away From Home

Richard Schnap

It was the place

I first performed in

On a night when

No one showed up

And it was the place

I found my ex-wife

Our eyes embracing

In the blinding smoke

For it was the place

I first discovered

Every beginning

Carries its own end

And now this place

Of broken music

Is a restaurant where

I dine with ghosts

|

No Pets Allowed

Richard Schnap

Sometimes it seems

Like a shadowy confession booth

Where I ask for forgiveness

For the sins I might commit

And sometimes it seems

Like a solitary prison cell

Where I serve out a sentence

For someone else’s crime

And sometimes it seems

Like a physician’s waiting room

Where I’m given a number

And told I will be called

But mostly it seems

Like a salesman’s cubicle

Where I deliver my pitches

And prepare for the reply

|

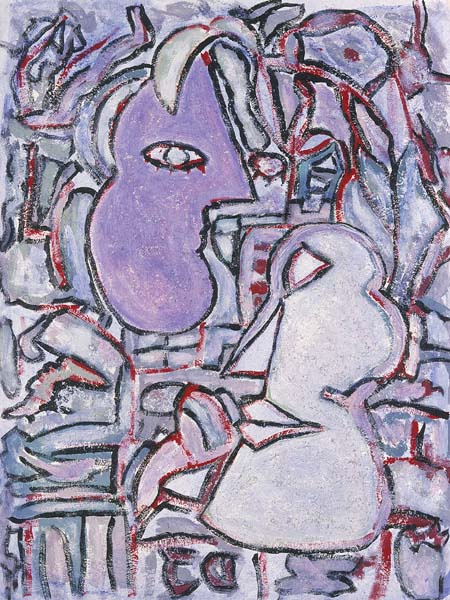

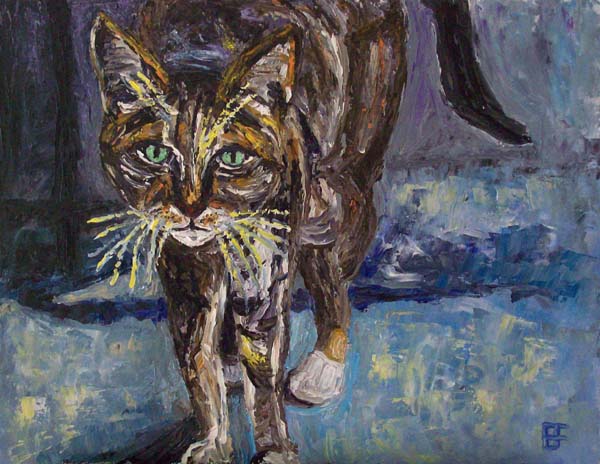

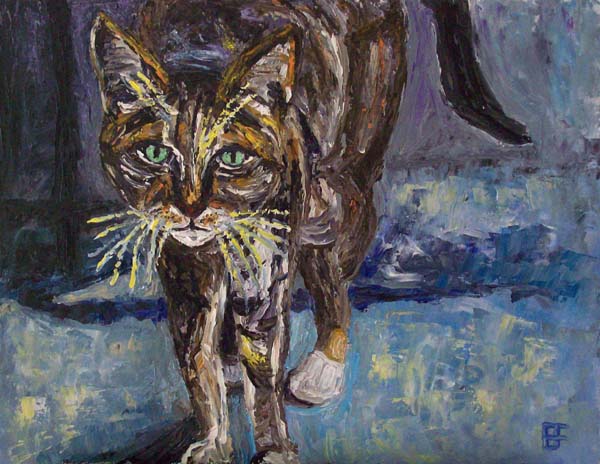

Brian Forrest Bio:

Born in Canada and bred in the U.S., Brian Forrest works in many mediums: oil painting, computer graphics, theatre, digital music, film, and video. Brian studied acting at Columbia Pictures in Los Angeles, digital media in art and design at Bellevue College (receiving degrees in Web Multimedia Authoring and Digital Video Production.) He works in the Seattle, WA area in design/media/fine art. Influenced by past and current colorist painters, Brian’s raw and expressive works hover between realism and abstraction.

http://brianforrest-art.blogspot.com/

|

freeing mermaids

Linda M. Crate

i’m more than all the things

you never said to me

or the pink and red

lipstick stains i left

down the

sides of your cheeks and lips

which you never

deserved,

but even the pied piper

fooled a dame or two;

i know now not to fall for the music if it’s

too sweet because if it’s too good to be true

it always is—

false and insincere

you struck with me with the crescendo

of mountains,

but i am a moon child

daughter of silver and waves

i will devour you in the eye of the storm and crash

my hurricanes into your mountains

free all the sirens

in your eyes;

because once they were just mermaids

with dreams.

|

i will live

Linda M. Crate

your mother was constantly offended

by me:

what i wore, what i said, if i talked

or if i didn’t speak;

i couldn’t win for losing

so when i lost you

it wasn’t as big a tragedy as i first thought—

because if i am to love

it will be a man,

and not a boy like you;

stuck in the cogs of a machine of people pleasing

you can’t see how foolish you are

consider yourself a saint and a genius

but you are neither—

i couldn’t live life the way you do

always afraid of offending someone because i am

not going to wax and wan into nothingness

like my moon mother

i am going to crash like her moodiest of waves

crash a few egos if i have to

because life is not meant to be lived in closed doors,

and i have had enough of keeping my toes

in line and walking on egg shells

they can choke on the yolk of my dreams if they must

i am me and that’s all i ever could be;

there will be no apology

for that.

|

Vanishing Scars

Janet Kuypers

2/9/16

“They tell you how it was...

and how it happened

again and again. They tell

the slant life takes when it turns

and slashes your face as a friend.”

— William Stafford, from “Scars”

Any wound is real, he says,

and yes, it’s true, I know it.*

For the faces of promise

are also the places

the scars will be.

Yes, bright-eyed children,

this is the battle

you have to look forward to.

Brace yourself,

if you know how.

It might hurt less then.

For once we are grown

we are all too aware

of past tortures and traumas,

they leave physical and emotional scars

we wear like badges,

while knowing

these scars

scar us.

Hide the marks from your face,

your stomach from when

you were hospitalized

against your will for months.

Hide the bruises around your neck

as you leave the country

to escape the man

who once claimed he loved you.

Force yourself to forget

the disappointing diatribes

your disappointment of a father

gave you, while you struggle

to be stronger than him,

despite him.

If you internalize some scars,

turn them around,

then watch your helplessness

transform to rage,

then to solace and insight

to help others recover

from their own physical

and sexual traumas.

They say that time heals all wounds,

and you wish for the scars to vanish;

your brutish, broodish demeanor

is a blemish

you wish would perish —

but wait a minute,

search for that scar

on the cleft of your chin

from when you scratched

when you had the Chickenpox.

You would swear

that scar was there,

but

where did it go.

Then you turn

to the one you love.

They tell you

they’ve never seen the scars.

That you’ve always been

a bright white beam of light,

almost too blinding

for anyone to fully take in,

which is why

you can never

be fully understood...

And this is all they think

when they see you,

and all they can say

is

I love you.

And maybe that

is the treatment

for the traumas...

and the scars

to hard

to handle.

Any wound is real,

for scars too hard to handle.

And any wound is real,

as long as you give it the power

to take over your soul

and fester into a fiendish demon.

So just remember

that despite those vanishing scars

that are now

too taxing to tally,

despite those battle scars...

you are a blinding light

that no one,

thankfully,

will ever

fully

understand.

Italicized portion of this poem are quotes

from the William Stafford poem “Scars”.

* line toward he end of the Ai poem

“The Good Shepherd: Atlanta, 1981.”

|

Juxtaposition,

or Irony?

Janet Kuypers

2/7/16

In Texas, you see

giant U.S. flags waving

and bumper stickers

to secede.

|

See a Vine video 2/7/16

of Janet Kuypers reading her twitter-length haiku (w/ bonus words) Juxtaposition, or Irony? during Super Bowl 50 as a looping JKPoetryVine video in Austin, TX (Samsung)

|

See a Vine video 2/7/16

of Janet Kuypers reading her twitter-length haiku (with bonus words) Juxtaposition, or Irony? after Super Bowl 50 as a looping JKPoetryVine video in Austin, TX (Samsung)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers’ 2 poems Arsenic and Syphilis & Juxtaposition, or Irony? from memory; then she read her 2 Periodic Table poems Potassium Chloride and Thallium at Georgetown’s Poetry Plus open mic at Cianfrani’s 2/26/16 (w/ a Cps).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers’ 2 poems Arsenic and Syphilis & Juxtaposition, or Irony? from memory; then she read her 2 Periodic Table poems Potassium Chloride and Thallium at Georgetown’s Poetry Plus open mic at Cianfrani’s 2/26/16 (w/ a Cps).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers’ 2 poems Arsenic and Syphilis & Juxtaposition, or Irony? from memory; then she read her 2 Periodic Table poems Potassium Chloride and Thallium at Georgetown’s Poetry Plus open mic at Cianfrani’s 2/26/16 (w/ a Nikon).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers’ 2 poems Arsenic and Syphilis & Juxtaposition, or Irony? from memory; then she read her 2 Periodic Table poems Potassium Chloride and Thallium at Georgetown’s Poetry Plus open mic at Cianfrani’s 2/26/16 (w/ a Nikon).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Protect Ourselves from Ourselves” and “Viewing the Woman in a 19th Century Photograph” 9/10/16 at “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library (Cps).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Protect Ourselves from Ourselves” and “Viewing the Woman in a 19th Century Photograph” 9/10/16 at “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library (Cps).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Protect Ourselves from Ourselves” and “Viewing the Woman in a 19th Century Photograph” 9/10/16 at “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library (Sony).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Pluto, Plutonium & Death”, “Your Minions are Dying” and “Salesman” 10/23/16 at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (Canon Power Shot camera).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Pluto, Plutonium & Death”, “Your Minions are Dying” and “Salesman” 10/23/16 at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (Canon Power Shot camera).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Pluto, Plutonium & Death”, “Your Minions are Dying” and “Salesman” 10/23/16 at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (from a Sony camera).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers saying her twitter-length poem “Juxtaposition, or Irony?” in conversation, then reading her poems “Pluto, Plutonium & Death”, “Your Minions are Dying” and “Salesman” 10/23/16 at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (from a Sony camera).

|

Unplug

Drew Marshall

Skateboarding down the four lane boulevard

He would look down at his foot to push off

Then back to his cell phone, smacking the keyboard

Never bothering to look around for passing cars

We were almost at the Penthouse

Before the middle aged woman realized

She had not pressed the button for her floor

After doing so, she continued texting

As the doors were closing

She finally looked up and hopped out

The lady did not move towards her destination

This addict continued playing with her device

The twenty something woman in physical therapy

Is laying on her stomach

Immersed in the video game on her tablet

Ankle weights on her feet

Lifting her legs up

One at a time, moaning

In between painful cries, back to the game

I will loose track of time

When I’m at home on my desktop

But I’m not in physical therapy or skateboarding

When engaging the internet

|

All the news that Fits

Drew Marshall

As per my social worker

As per Dr Andrew Weil

As per my common sense

Several times a year

For several weeks

I try to avoid the news

A daunting task

In this age

Of the information revolution

During those wonderful weeks

I remain, a uniformed citizen, in bliss

I receive a Classic Rock Newsletter

I know who died

What CDs, are being reissued

The artist’s who are touring

At this point

I don’t need to know much else

|

Red Mittens

Judith Ann Levison

He sighed, drank a shot with a pill,

Knew his dramatic sister was in from Paris

To relate near affairs, all going nowhere.

Always tidying his eclectic apartment

His mother sent plaid grey scarves

And his father played pool with a vengeance

For he was denied a pension, denied success

None of this interested him

Outside the bus window the snow stalled

It would dissipate or make a show of it.

The man with baggy eyes beside him

Was quite keen on old cars, antiques and

Never went to church—all that death,

Misused authority, and weeping.

On his right a woman declared everyone

Had their own lodestar angel of light

You just had to look for it.

Then he saw a little curly haired girl turning

Her red mittens over and over

She sniffed the inside of each and bit

The string that bound them

Her brother then grabbed them, with raw laughter

Tossed them in the slushy gutter

|

BR>

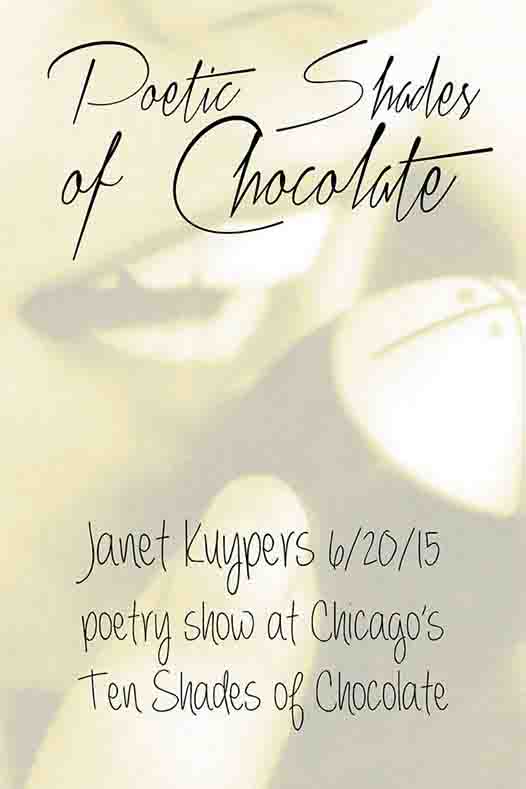

See YouTube video of the 6/20/15 Janet Kuypers show “Poetic Shades of Chocolate” in 10 Shades of Chocolate in 10 Shades of Chocolate in Chicago (Cfs), w/ the poems Under his Bed, oxygen to flame the fire, Fuming in the Morning, PDQ in Tin Foil 2015, melted marshmallow 2015, grandmother charged with murder 2015, Before Taking Over the Controls 2015, and Empty Chocolate Counter.

See YouTube video of the 6/20/15 Janet Kuypers show “Poetic Shades of Chocolate” in 10 Shades of Chocolate in 10 Shades of Chocolate in Chicago (Cfs), w/ the poems Under his Bed, oxygen to flame the fire, Fuming in the Morning, PDQ in Tin Foil 2015, melted marshmallow 2015, grandmother charged with murder 2015, Before Taking Over the Controls 2015, and Empty Chocolate Counter.

|

See YouTube video of the 6/20/15 Janet Kuypers show “Poetic Shades of Chocolate” in 10 Shades of Chocolate in 10 Shades of Chocolate in Chicago (Cps), w/ the poems Under his Bed, oxygen to flame the fire, Fuming in the Morning, PDQ in Tin Foil 2015, melted marshmallow 2015, grandmother charged with murder 2015, Before Taking Over the Controls 2015, and Empty Chocolate Counter.

See YouTube video of the 6/20/15 Janet Kuypers show “Poetic Shades of Chocolate” in 10 Shades of Chocolate in 10 Shades of Chocolate in Chicago (Cps), w/ the poems Under his Bed, oxygen to flame the fire, Fuming in the Morning, PDQ in Tin Foil 2015, melted marshmallow 2015, grandmother charged with murder 2015, Before Taking Over the Controls 2015, and Empty Chocolate Counter.

|

Download these poems in the free chapbook

Poetic Shades of Chocolate

w/ poems read 6/20/15 at 10 Shades of Chocolate show in Chicago

|

oxygen to flame the fire

Janet Kuypers

5/11/15

kept trying to describe him to my friends.

i mean, it was such a red-hot relationship,

sometimes our love would burn so bright

and sometimes it would seem like we’re nothing.

because now i’ve figured him out and now

it all makes sense. he was a cigarette.

our time together was so short, and like those

nicotine sticks, it burned out too fast.

when he was getting me all hot and bothered,

i’d take a deep breath, suck in some oxygen

to flame this fire between us —

and her glowed with a red-hot intensity.

but whenever he got bored with me

he just made ashes of our relationship

and all that was left was a smoke trail,

and a smell i couldn’t name in the air.

everyone was telling me he was no good.

but i didn’t know better. i couldn’t help it.

i was intoxicated — but now that he’s gone

i wonder how much pain this affair has caused.

i wanted to be free. i tried many times.

but it was like he had this spell over me.

i was an addict. i just sucked him in,

adding fuel to the fire that was once our love.

|

Under his Bed

Janet Kuypers

5/27/15

We hadn’t dated that long,

we’re not that close...

and

he brought me to his bedroom,

sat me down on his bed,

and said he had something to show me.

My legs are now hanging

over the side of his bed

and he says,

“Hold on a minute”

and he gets on his knees.

And I’m thinking,

“What does he want to show me?”

But then, while he’s on his knees,

he reached under his bed.

I was sitting there, my legs

were dangling over the edge

and I couldn’t see what he was doing —

until he got up off the floor

and placed the black objects on the bed.

“What is this?”

I ask.

“They’re knee pads,”

he answered.

So he’s brought me

to his bedroom,

I’m sitting on his bed,

and he’s showing me knee pads.

There was no explanation,

he just brought me

to his bed

to show me knee pads.

So my mind goes into overdrive.

Why did he bring me in here

to show me these? I mean,

we’re not that close,

we havent dated that long,

but is this something he needs

for some sort of sexual act?

Is he concerned about

my scrped knees if I’m getting

him off? My eyes were saucers,

and all I could ask was,

“What are these for?”

He started to grin.

“I just got roller blades,”

he answered,

which I hadn't seen

and didn’t know.

But as I said,

we hadn’t dated that long,

we’re not that close,

so all I could think

when he brought me

to his bedroom

and showed me new gear

he kept under his bed,

all I thought

was that this was

the most bizarre way

to ask someone for the first time

for safe sex.

|

Empty Chocolate Counter

Janet Kuypers

5/21/15, edited for 6/20/15 show 5/31/15

I used to save what change I could when I was little

and I’d ride my bike to the Plush Horse ice cream parlour

to get a scoop of their chocolate chocolate chip ice cream

(that’s chocolate ice cream with chocolate chips)...

But once I got a job there,

only boys were allowed to scoop ice cream there.

But it was under new management —

the brother of the owner of Dove chocolates

took it over, and I was hired

to work for their brand-new candy counter.

So now, for the first time,

this ice cream parlour was open year round,

and I was there to sell chocolates.

So, in the winter

it’s safe to say

it wasn’t very busy.

I was there in the winter

to sell chocolates to no one

along side the designated male

ice cream scooper...

Now, I couldn’t get away

with eating the individual chocolates for sale there,

they’d keep track of their inventory,

but their ice cream,

made in the back room,

was harder to keep track of.

So, every time I worked in the winter

I’d make myself a twenty-for ounce

chocolate chocolate chip shake

out of chocolate ice cream with chocolate chips

(and added fudge, of course).

But one Tuesday night in February,

I was sitting in a chair behind my counter,

with my precious chocolate ice cream

and chocolate chip shake, with fudge —

my shake was in my hand

as the side door opened,

right in front of my counter.

And that’s when the owner,

came through the door.

So I stashed my shake under the counter

and stood at attention.

“Hello, how are you sir?” I asked,

and he just grumbled,

mumbled he was fine

and he walked to the back office.

Whew...

But another day at work with the boss,

when deliveries were dropped off,

I picked up a larger box

and the owner then stopped me.

“Wait, that’s heavy —

you shouldn’t carry that.”

And I laughed, explaining that I carry

fifty pound salt blocks for our water softener,

that I’m fine.

I think maybe him seeing

that women can stand up for themselves

made it okay, in the heat of summer

when the lines are out the door for ice cream,

for me to leave the empty chocolate counter

and be the first girl there

to ever scoop ice cream with the big boys.

#

Looking back, you may say

I’m a feminist pioneer

by being the first female

to scoop ice cream there,

but when I look back

I don’t see it that way.

I just remember home-made

chocolate ice cream

with chocolate chips,

molasses bits and added fudge,

and that, my friends,

was whipped

into the perfect shake —

no matter which gender

did the work.

|

Fuming in the Morning

Janet Kuypers

5/11/15

When I wake up every morning,

unlike everyone else,

I rip the blankets off of me

because I’m boiling hot.

Been trying to figure out why.

When I wake up every

morning alone,

I wonder if my missing you

manifests itself

by leaving me tossing and turning

in my dreams,

until I wake up in a sweat.

These must be my red-hot thoughts

percolating up inside me

in the middle of the night,

leaving me fuming in the morning.

This is what I wonder.

Is this what being without you

makes me do.

I think I run to you all night long.

When I go to bed at night

after a day without you, I’m ice cold.

But my brain spends hours

throughout the night in my sleep

thinking about us together.

Thinking about trying to find you.

It spends hours thinking about

what being without you means.

And I wake up,

like I do every morning,

after feeling like I’ve mentally

run a marathon,

and I go about my day, alone.

Life makes me cold again.

And I wonder what it takes

to get back to you again.

|

|

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006.

She sang with acoustic bands “Mom’s Favorite Vase”, “Weeds and Flowers” and “the Second Axing”, and does music sampling. Kuypers is published in books, magazines and on the internet around 9,300 times for writing, and over 17,800 times for art work in her professional career, and has been profiled in such magazines as Nation and Discover U, won the award for a Poetry Ambassador and was nominated as Poet of the Year for 2006 by the International Society of Poets. She has also been highlighted on radio stations, including WEFT (90.1FM), WLUW (88.7FM), WSUM (91.7FM), WZRD (88.3FM), WLS (8900AM), the internet radio stations ArtistFirst dot com, chicagopoetry.com’s Poetry World Radio and Scars Internet Radio (SIR), and was even shortly on Q101 FM radio. She has also appeared on television for poetry in Nashville (in 1997), Chicago (in 1997), and northern Illinois (in a few appearances on the show for the Lake County Poets Society in 2006). Kuypers was also interviewed on her art work on Urbana’s WCIA channel 3 10 o’clock news.

She turned her writing into performance art on her own and with musical groups like Pointless Orchestra, 5D/5D, The DMJ Art Connection, Order From Chaos, Peter Bartels, Jake and Haystack, the Bastard Trio, and the JoAnne Pow!ers Trio, and starting in 2005 Kuypers ran a monthly iPodCast of her work, as well mixed JK Radio — an Internet radio station — into Scars Internet Radio (both radio stations on the Internet air 2005-2009). She even managed the Chaotic Radio show (an hour long Internet radio show 1.5 years, 2006-2007) through BZoO.org and chaoticarts.org. She has performed spoken word and music across the country - in the spring of 1998 she embarked on her first national poetry tour, with featured performances, among other venues, at the Albuquerque Spoken Word Festival during the National Poetry Slam; her bands have had concerts in Chicago and in Alaska; in 2003 she hosted and performed at a weekly poetry and music open mike (called Sing Your Life), and from 2002 through 2005 was a featured performance artist, doing quarterly performance art shows with readings, music and images.

Since 2010 Kuypers also hosts the Chicago poetry open mic at the Café Gallery, while also broadcasting the Cafés weekly feature podcasts (and where she sometimes also performs impromptu mini-features of poetry or short stories or songs, in addition to other shows she performs live in the Chicago area).

In addition to being published with Bernadette Miller in the short story collection book Domestic Blisters, as well as in a book of poetry turned to prose with Eric Bonholtzer in the book Duality, Kuypers has had many books of her own published: Hope Chest in the Attic, The Window, Close Cover Before Striking, (woman.) (spiral bound), Autumn Reason (novel in letter form), the Average Guy’s Guide (to Feminism), Contents Under Pressure, etc., and eventually The Key To Believing (2002 650 page novel), Changing Gears (travel journals around the United States), The Other Side (European travel book), the three collection books from 2004: Oeuvre (poetry), Exaro Versus (prose) and L’arte (art), The Boss Lady’s Editorials, The Boss Lady’s Editorials (2005 Expanded Edition), Seeing Things Differently, Change/Rearrange, Death Comes in Threes, Moving Performances, Six Eleven, Live at Cafe Aloha, Dreams, Rough Mixes, The Entropy Project, The Other Side (2006 edition), Stop., Sing Your Life, the hardcover art book (with an editorial) in cc&d v165.25, the Kuypers edition of Writings to Honour & Cherish, The Kuypers Edition: Blister and Burn, S&M, cc&d v170.5, cc&d v171.5: Living in Chaos, Tick Tock, cc&d v1273.22: Silent Screams, Taking It All In, It All Comes Down, Rising to the Surface, Galapagos, Chapter 38 (v1 and volume 1), Chapter 38 (v2 and Volume 2), Chapter 38 v3, Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite (Volume 1, Volume 2 and part 1 of a 3 part set), A Wake-Up Call From Tradition (part 2 of a 3 part set), (recovery), Dark Matter: the mind of Janet Kuypers , Evolution, Adolph Hitler, O .J. Simpson and U.S. Politics, the one thing the government still has no control over, (tweet), Get Your Buzz On, Janet & Jean Together, po•em, Taking Poetry to the Streets, the Cana-Dixie Chi-town Union, the Written Word, Dual, Prepare Her for This, uncorrect, Living in a Big World (color interior book with art and with “Seeing a Psychiatrist”), Pulled the Trigger (part 3 of a 3 part set), Venture to the Unknown (select writings with extensive color NASA/Huubble Space Telescope images), Janet Kuypers: Enriched, She’s an Open Book, “40”, Sexism and Other Stories, the Stories of Women, Prominent Pen (Kuypers edition), Elemental, the paperback book of the 2012 Datebook (which was also released as a spiral-bound cc&d ISSN# 2012 little spiral datebook, , Chaotic Elements, and Fusion, the (select) death poetry book Stabity Stabity Stab Stab Stab, the 2012 art book a Picture’s Worth 1,000 words (available with both b&w interior pages and full color interior pages, the shutterfly ISSN# cc& hardcover art book life, in color, Post-Apocalyptic, Burn Through Me, Under the Sea (photo book), the Periodic Table of Poetry, a year long Journey, Bon Voyage!, and the mini books Part of my Pain, Let me See you Stripped, Say Nothing, Give me the News, when you Dream tonight, Rape, Sexism, Life & Death (with some Slovak poetry translations), Twitterati, and 100 Haikus, that coincided with the June 2014 release of the two poetry collection books Partial Nudity and Revealed.

|

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

|

Always

Charles Hayes

Above the quietness of this little high hollow spot the high pitched call of a Red Tailed Hawk brings my eyes to the sky. Taking a break from the garden work, I watch the large bird float about on the updraft. There is something about watching a hawk on the wing. It draws up a feeling of freedom from the gut. Like hot smoke up a cold flue, it comes naturally, un-worked. Nice. But, telling myself that this sod is not going to get busted if I stand here and look to the sky, I start to go back to breaking up the clumps of dirt. That’s when I see Julie Lewis walking up the dirt road. Dressed in simple jeans, an old hooded jacket, and sneakers, she crosses the little footbridge over the creek and right up to the garden. Stumbling while crossing the clumps of dirt, her unsteadiness betrays her weariness, and I know that she has walked a ways to get here. Big brown eyes present to mine with a sincerity that is not that common around here. Around here it’s mostly lore or ribald tales of one kind or another with a kind of sincerity that is saved for after the punch line. Like an innocent look with an “I swear to God” kicker. Perhaps most real sincerity is too soft for the hard sticks of this part of Appalachia. But even tired, those haunting eyes in a face too young for wrinkles, together with her long coal black hair and comely figure make Julie an attractive woman.

The last time I saw her was right after she married a guy from the next hollow over. I knew then that it wouldn’t last. One day when I was visiting the area to look at some of their goats, her husband, Jack, was at work and I hit on her. She liked it at first but when I tried to take her pants off she got cold feet and put an end to it. A little surprised that she had gone that far, I knew then that it was another one of those marriages that happen in this land of scarcity. I left on friendly terms with her and with a little more respect, though I knew her hardly at all. Just that, like me, she had come into this area from somewhere else.

At first I smile as Julie just stands there for a moment. But her face is so serious that it quickly melts my expression. Did my pass at her cause trouble that is now coming home to roost? As if to reassure me about that, she finally says, “Don’t worry, nobody knows that you came on to me.” Seeming to try to put together her thoughts while I quietly watch, she looks to the busted earth, bends down, and fingers an earthworm from the broken ground. Watching it wiggle in her palm for a moment, she drops it aside, stands and seems to brace for some kind of hurt.

“You’ve got no phone, Richard,” she says, “else I would have called. So you can take the seriousness of my being here by the number of miles I’ve walked.”

Thinking that this is the first normal talk that I’ve ever heard from Julie, and at the same time recognizing the intelligence and poise that she brings to it, I try to be encouraging, something I‘m not used to.

“Yes, I can see that,” I say. “I sure hope you’re about to tell me what brings you so far up this way. Is there something that you need some help with?”

Her eyes never leaving mine, like they are locked there by her need to miss nothing, Julie replies, “Jack and I didn’t make it. I think you knew that we wouldn’t. Else why would you have acted toward me the way you did.”

Pausing and lifting her eyebrows, Julie makes her point before continuing.

“I don’t know anybody other than you who is not a friend of Jack’s. I could tell when you tried to bed me that you were not a violent person. From the ways I’ve been, that is no small matter. Can I live with you?”

Having gotten out what she carried miles to say, Julie steps back a couple of paces and looks to the ground.

Never in my days have I been called upon under such circumstances and, though it has been plenty lonely around here, all of a sudden that doesn’t seem the bane that it was. When stacked beside a mismatch with another human being, it’s suddenly small potatoes. But in this land of obscurity and want, there is in Julie and the way she touches me, something that tells me not to run from what isn’t there. Dropping the hoe and feeling a favor pretty uncommon in my life, I say, “Let’s go inside Julie. There’s coffee, not so good, but coffee just the same. And you should see the innards of this place before we go any further.”

I can imagine the edge of Julie’s lips turning the smallest amount. As we walk toward the house we exchange glances, both of us continuing to inspect one another a bit. Trying to bring a little lightness to the situation, I offer up a pretty common question around here.

“Where you from, girl? Your speech and manner are not from around here.”

“New York,” she replies. “Where are you from?”

“Just a couple of mountain ranges over,” I say, “in the Coal River Valley, little place called Dorothy, not big enough for a stop light.”

As we cross the yard my two beagles are all noses and whipping tails as they inspect Julie. A good sign that she acknowledges with a couple of pets and kind words.

“Is that New York City?” I ask as we climb the two steps to the rough back porch and kitchen door.

“Brooklyn,” she replies.

Moving in with her cardboard suitcase, Julie takes up the little cot in my spare room where I keep most of my gun collection. For the first week or so we sort of get used to having each other around. She is good with the little wood stove and up before me to start or stoke it on the cold early spring mornings. And if need be, she doesn’t mind going to the well to draw water. The dogs love her regular feeding routine and, all and all, she is a good house mate. Plus I have more time for my cartoons, which a couple of papers pay me for. Not much, but enough for subsistence living. Neither of us expected more than that when we chose these hard rocks of living to begin with. But there is still that not so natural space between us. I try to show that I don’t need to jump into her pants to get along, give her space to drop the load I know she arrived with. Plus I am now living with her, not just passing by. To me there is a difference. Sometimes I think she knows this as we share coffee in the morning. There is a look in her eyes that reminds me of one of my funny characters—the would be girlfriend of a shy boy from the same block. But Julie shortly puts an end to all this. After getting the fire going one morning, she strips and comes to my covers to wait for the house to warm up. The change is not big. But certainly enough to soften our steps a little.

As onion sets turn to glossy green shoots and cabbages begin to look like broad fanned bonnets, spring warms to summer. Pretty quick it seems, Julie receives her mail order divorce without any trouble. The local law center was glad to do it with only one visit by a paralegal. My presence was treated as if it’s not uncommon to have divorces lagging behind new partners. Jack and his large clan were happy to be rid of the “City Girl” on an even-steven basis. Truly their differences were irreconcilable and neither had money nor property to fool with.

Having spent part of my life in resourceful areas, I know that one thing about the sticks that blessedly doesn’t tick in divorces are battles over wealth of one kind or another. Maybe, I consider, that is one reason why conjugal unions here are not the capital deal that they are some places. So Julie and I become as married as many people around here ever become....without the back speak of being married to someone else.

Kneeling on the couch and looking out the window to the far ridges beyond the lower end of the hollow, divorce papers scattered at our knees, Julie and I sip a rare cup of tea using the window ledge as our table. It is a time for reflection as we playfully clink our cups and smile at each other and the pretty view. Admiring the luster of her look as she gazes at the hazy mountains, I feel a goodness that moves me above the coarse, the practical. Something that would have scared the shit out of me before Julie.

Noticing my stare, Julie blushingly laughs and locks me with those pools of brown.

“What,?” she asks.

Thinking that to put into words my thoughts would be too wide open, I simply shake my head.

Julie places her tea on the window ledge beside mine, puts her arms around my neck and pulls me over her as we slide to the couch.

“Tell me Richard,” she says, “I want to know about you.”

A scent of lemon comes with her words and seems to float above her face and the nest of raven hair that holds it. My embarrassment melts as I realize that I can not deny this woman.

“I was thinking how nice it is that we are here together,” I say. “Like something made to be that way. You and me.”

Julie’s eyes well up as her words catch in her throat. After a moment, feeling like she has been called from afar, she whispers.

“Come here you.”

It’s an easy stroll out of the hollow to the lazy Greenbrier river that meanders through the little towns and countryside of this part of the wrinkled earth. Imagining ourselves a little like the Seneca Indians that used to roam and live along these banks, Julie and I set a couple of fish lines, start a small fire, and strip down to our swim wear. Somewhere in that cardboard suitcase Julie must have found a beautiful rainbow bikini. The way she wears it with the high sun flashing from its colors reminds me of Frank Sinatra’s Girl From Ipanema. However, I figure that Julie is just as nice as any girl along Frank’s Brazilian beach.

Using an old rope swing in a nearby River Sycamore, I teach Julie how to swing out over the water and drop in. I have never seen a girl that was able to do this kind of thing because of the arm strength required but Julie picks it right up. So lovely and bright as she arcs from the tree shadow into the sunlight, she seems to leave a contrail of beautiful flesh and color to savor. We even manage to both ride the rope out together, dropping into the clear stream, the yellowish green glow of its sandstone bottom clearly visible before it swallows us. Far across to the other side and near a heavily wooded bank a beaver disapprovingly tail slaps the water.

By the time we are done with our water play our appetite is built. Cutting a couple of small green branches, we roast hot dogs and enjoy the thoughts that a slow stream of passing water can bring.

While reclining by the embers and admiring Julie’s lithe figure for the umpteenth time, I see the small thin scar just above her bikini line. Something that I had noticed before but never mentioned, thinking that if I needed to know she would tell me. I trace the line with my finger and lift my eyes to her.

After holding my look, Julie looks to the river as a shadow passes over her face. Finding in the waters what she was looking for, she brings her eyes back to mine.

“I can’t have babies,” she says. “About three years ago I had stage three ovarian cancer and had to have my ovaries removed. They thought that they got it all but that’s the price. I’m sorry, Richard.”

The way Julie says this leaves me with questions that she must know are going to follow because she suddenly looks defensive. And Julie is not the defensive type.

“Hey darling,” I say. “I’m not into kids. Child free suits me just fine. There’s plenty around to take any of mine’s place to start with.”

Pausing to poke around in the coals with my stick, I too look for the words to go where I need to go. Where Julie, I can tell, doesn’t want to go.

“You’ve become a pretty import part of my life,” I say. “Thank God you got through it. Was this in New York?”

“Yes. It was all pretty simple. I was in and out of the hospital in a couple of days. They wanted me to do a regimen of chemo then get retested but I refused.”

Beginning to see where she is coming from, I can’t help but get a little uneasy.

“Why babe?”

“Why what?”

“Why did you refuse?”

Taking a deep breath, then letting it go, as if the extra air was needed to continue, Julie opens the gates to a part of herself that had been closed.

“Because I’d had enough,” she says. “I’d lost my reason to be a woman. Now they wanted me to give up even my appearance of being a woman. And get sick to boot. Plus they couldn’t really tell me why except a bunch of mumbo jumbo. Expensive mumbo jumbo. I was just another poor Jewish girl with no health insurance to them, one that must have money somewhere in the family tree. But there is no tree. I am it. And until I met you, not much of an it.”

For the first time, perhaps getting an inkling of what brought Julie to this obscure land, I can see all of her. And that makes her precious. Too precious to push because of my ins and outs. I can only accept this woman that I have fallen in love with for what she is. And this, indefinably, puts a little edge to who I am.

“Ok Julie,” I say, “but if you decide that things aren’t right we can get help. There are ways. Don’t ever feel that you must go without.”

Falling silent, we sit by the dying fire and watch the shadows grow long. I throw another drift log on the coals, watching the fast smoke chase the mosquitoes. Sounding like a .22 rifle shot, the beaver pops a tail, wishing us long gone as the sun kisses the ridge. But we are not moving. Julie leans her head on my shoulder and we stare at the smoking log, waiting for it to burst into living fire.

***

The mountains are aflame with red and orange colors as the autumn winds send their leaves tumbling across the garden. Picking and husking the last of the yellow bantam corn, Julie and I leave a back trail of weathered husks and apple butter colored silk. Dropping the fat yellow ears into a shoulder bag, we move along, a duet of rhythm. Julie will eventually shave the surplus ears and can the rich kernels for the coming winter while I block and bust up some downed timber for the wood burner. The garden has been good to us and the Beagles, their favorite time of year at hand, have helped with bringing in some protein rich game to go with the vegetables. Fall has always been my favorite time. A time when past and future meet in one clear display. Thought is heavy, looking to the test of hard weather ahead, yet carrying the satisfaction of a recent harvest and vigilant preparation.

Finishing up the last row and dropping her sack on the back porch next to mine, Julie suddenly holds her stomach and goes to her knees. Like a person I had once seen shot in the gut, she tips over to her side and curls into a fetal position, grimacing in pain.

Dropping the garden rake, I run over and drop to the ground next to her. Holding her head above the grass and seeing her face twisted in pain, I am scared shitless.

“What’s wrong, Julie, Please tell me babe, what’s going on.”

With her eyes squeezed shut and her breath coming in short gasps, she reaches up and pulls my head to. In not much more than a whisper she says, “I think you’d better get me to the emergency room, Richard. I’m hurting something fierce in my guts. It feels like something ruptured down there.”

Half carrying, half dragging Julie over to the old jeep that we use for groceries and emergencies only, I strap her in and get us to the hospital which is just down river a few miles and across a bridge. When the E.R. staff see her condition they take her right in and have me wait outside.

Sitting in the waiting room for what seems like a couple of hours, first filling out paperwork, then just trying to come to grips with being in a place where people die, I am pretty anxious. Not since the war and its grind of human loss have I felt like this. And that was mostly for my own skin. This is new. What if I lose Julie. In a morass of emotions, I don’t see the ER Doctor until he puts his hand on my shoulder.

A dark kindly looking man of middle eastern descent, wearing a white coat with a stethoscope sticking out of the pocket, he takes a chair next to mine. As he sits I notice that his name tag says Dr. Amjad.

“You are Richard Jones,” he asks, “the husband of Julie Lewis?”

It is the first time that I have ever been called a husband and suddenly I realize that this is about me as well as Julie.

“Yes,” I say. “Is she ok? What’s wrong?”

“I have admitted her,” Dr. Amjad replies. “She is sedated and fine for now, but her preliminary tests together with her medical history suggest some serious problems. She said that you know a little about it.”

Thinking that the only thing that I know about is her previous cancer, I ask Dr. Amjad, “Does she have cancer, can you fix it?”

“We suspect that a piece of malignant ovary was not removed properly,” Dr, Amjad says. “According to our imaging, it has grown into a sizable tumor. We will remove it as soon as possible, and that should help some with the pain. But considering metastasis and the amount of time that it has been growing, her prognosis is quite guarded.”

Dr. Amjad pauses for questions but I mostly understand what he is saying. All of my what if thoughts have seen to that, so he quickly continues.

“She feels that chemotherapy will make her sicker and any benefit from that may be questionable to begin with. Once the surgeon has a look things will become clearer. But our oncology unit will do what it can. For now she needs all the support that she can get. She is in room 202. When she is able to talk why don’t you let her tell you how she feels. She has a great deal of concern about you. That is where I suspect you can help her most. Just go to the second floor nurses station. They will be glad to direct you. Now, if you will excuse me, I must get back to my other patients.”

Watching Dr. Amjad disappear through the white swinging doors, I can feel my heart sink to my stomach. Suddenly I feel hollow inside, like a once full vessel ripped of its contents in an instant. Going to the bank of elevators, I press the up button and hope that I can be what Julie needs. All the way.

On the way home from the hospital, Julie and I detour to Sandstone Falls and its little park. Walking out a ways on the boardwalk, we sit watching the cascading water drop and pass below our observation bench. The trees are mostly bare with just a few scattered evergreens and die hard poplars adding patches of green and orange to the steep grey timber around us. Watching the water swirl, spitting curls of white froth as it passes over the rocks, we hold hands and pull our collars close, the November nip reminding us of an approaching winter. Julie’s far away look, lacking the pleasant aura it used to wear, breaks my heart but I do my best not to show it.

Tracing a raised tendon on the backside of my hand with her finger, Julie breaks the back noise of rushing water.

“I hope I can make it without much pain,” she says. “You’ll have all the planting to do by yourself in the spring. When the time comes I hope the earth can be the purest white of snow. I always loved the snow. It makes me feel clean and new. Loved.”

Feeling busted inside and swept along like the waters beneath us, I try to put on a face.

“Don’t be silly Julie, you’ll be here. Of course you will be here.”

Gripping me with her look, Julie lifts her eyebrows in that way she has. For a moment I feel like a liar and am ashamed. Dropping the sham, I can only say what is.

“Know that I love you more than words can ever tell, Julie. Just as the sun rises and beyond, I will always love you.”

Dropping her eyes to my hand, Julie seems to see it for the first time. Lifting it to her lips, her face covered by falling hair, she trembles.

I cry too.

***

The yellow daffodil bonnets seem to shoot from the earth daily as spring opens its door and a tough winter subsides. Redbud trees near the hollow’s rising woods are glorious in their displays. And the grass has once again called the lawn mower out of my tool shed for its yearly maintenance. But I can not feel the new life appearing all around me. There is no joy. Someone once said that April is the cruelest month and now I know for sure what they meant. Julie sleeps most of the time, the time is near. But we are both thankful to have been given the winter together and the small meaningful Christmas that we shared. A palliative care nurse makes a round every couple of weeks to make sure that we have the morphine injections necessary for the increasing pain. The other related medicines mostly just set in the other bedroom along parts of the gun rack. It’s a strange almost surreal feeling I get on the rare occasions that she has a use for them. When I see them lined up there and paired with my guns I choke. I still let the dogs run for fun but I had to give up hunting. I only keep a couple of house guns now. The couch has become my permanent bed except when Julie wants company and that is not much now. And it’s easier from the couch to feed the fire and stay attuned to Julie’s needs during the night. Sometimes, like now, I just sit by the bed watching her. When her eyes twitch a little I wonder where she is and what she is dreaming. And I hope that I am there too. Being with her is everything.

Slowly opening her eyes, Julie looks to me and turns her near hand over for me to hold.

Taking her hand, I look out the bedside window and see an Easter snow beginning to rapidly cover everything.

Squeezing my hand slightly and with the barest voice, Julie says, “It’s time, Richard. You be good and always know that I am here. I will help you. I love you. We will always be.”

Suddenly grimacing in pain, Julie’s eyes grow large for a moment as I reach for the needle on the nightstand. But before I can administer the morphine Julie stops me. In the clearest voice that I have heard from her in many days she says, “No Richard, now you must help me....in another way. Look under the window sill.”

Moving around the bed to the window, I see nothing under nor on the window sill. Looking to Julie to tell her that there is nothing there, I am stopped short as she reads my expression.

“Lift up on the center part,” she says, again showing a wave of sharp pain.

Pulling up on the sill, I see a small hidden pocket containing a large ampoule of morphine. Enough for a week or more. Knowing what it is for, I start crying but pick it up anyway.

Using only her eyes, those soulful brown lights of life, she brings me back to my chair and again whispers me close.

“Because I love you,” she says, “I know you can do it. It will be fine. I’ll still be here. Just let me go from the rest, Richard. It is time.”

Julie’s eyes follow my movements as I fully load the needle, leaving only a trace amount in the ampoule. I have to stop and wipe my tears away a couple of times to see what I am doing. And each time Julie whispers encouragement, helping me along with each of the little steps.

When it is done and both her hands are turned to me, I take them as she shows the faintest smile before her eyes close. Laying my cheek to her, I silently weep as Julie, in three shallow breaths, leaves her words.

“Thank you....my dearest...love.”

***

Two Red Tailed Hawks, mates I suppose, circle high above the waters of the Greenbrier River as I stoke the little fire and make ready near the old rope swing and Sycamores. On a nearby river rock the old beaver perches and stares. It is the first time that I have ever seen it out of the water. New growth is all about from the spring rains and the current flows swiftly, cold but fresh and clear. Julie and I adopted this river as our own and loved it for it’s continuity—-flowing, no beginning, no end. We thought of it like Siddhartha’s flowing waters, and how they imitate life. Always here but never in one spot. Julie is like that and that’s how we feel. Always residents together and in touch, but moving.

Removing her urn from my backpack, I carry it out thigh deep in the stream of current as the Red Tails kite their floats of freedom, sending shrieks among the ridges. The beaver turns to get a better view and starts sounding, like a crying infant.

Unscrewing the top of the urn, I pour a little of Julie’s ashes into my hand and let them slowly sift through my fingers to the passing current. Looking to the sky, I see the hawks weaving peaks and dips around each other. The beaver, now in the water, salutes with a smart tail slap. Then they wait on, watching.

Pouring the rest of her ashes to my hand, I let them fall to the freedom of the current. No beginning, no end. Always a part of what is.

We love her.

|

Charles Hayes bio

Charles Hayes, a multiple Pushcart Prize Nominee, is an American who lives part time in the Philippines and part time in Seattle with his wife. A product of the Appalachian Mountains, his writing has appeared in Ky Story’s Anthology Collection, Wilderness House Literary Review, The Fable Online, Unbroken Journal, CC&D Magazine, Random Sample Review, The Zodiac Review, eFiction Magazine, Saturday Night Reader, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Scarlet Leaf Publishing House, Burning Word Journal, eFiction India, and others.

|

symptoms (of madness)

Patrick Fealey

down by the nightmare, the smell of burnt leaves hangs over the bank. it’s yesterday spoiling our dreams. the dead are never fully digested, just as the beautiful are never fully ignored. i was staring at the starer. the starer stared back. the wall was the best. it was blank and white and hurt less than colors and wallpaper patterns. i was pretty sure this meant i was insane.

YEAH, IT IS FUNNY HOW A MUSTACHE ISN’T ALWAYS WHAT ONE EXPECTS. I SAW A BARE-FOOTED BLACK HONDA STRETCHED OUT IN THE TREE-TOPS. I TOOK SIX SHOTS BEFORE I REALIZED IT WAS DEAD AND I COULDN’T EAT IT. AND HERE WE GO, THE HEDGER IS AT IT, ALWAYS AT IT WITH HIS SHEARS AND DUST MASK. ROBBING THE TREES OF THEIR LEAVES WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM BLACK & DECKER AND THE ELECTRIC COMPANY’S IN THERE TOO, IN ON A PIECE OF THAT AESTHETIC OF STRAIGHT BRANCHES SQUARED AND FLAT LIKE THE WORLD BEFORE COLUMBUS. I MUST LIVE ON A REGRESSIVE STREET. WHERE ARE THE ANGELS WHEN INSANITY ABIDES LIKE THE SEA? ROLLING COMING. ROLLING GOING. BUT NEVER GOING GOING.

the artist i had met in san francisco, malakami, and a girl from the villa spaghetti, shared our space on the east side of providence. it was the third floor of an enormous house. when malakami saw me staring at the wall he bought a plane ticket to hawaii. he was afraid of me, he said later. he was my friend and had been drawing art to go with my short stories. he was a skateboarder and skeptic, read h.p. lovecraft and was a pinball wizard. malakami was one of those beautiful people who acts harmless. malakami abandoned me, but he’d been working on it for awhile.

when i’d taken him in at the villa spaghetti, we were a pair of nocturnal heathens. i wrote and malakami drew. we went to bars and we broke open the night. then we moved to providence and he became a contrarian and took a step back. he disagreed with me so often it was impossible to talk with him. his patent response to everything was a deflective “really?” and that’s all he’d offer. no thoughts to follow it, just the hanging dismissal, which got to sounding idiotic in its repetition. he didn’t believe anything. “malakami, i saw your girlfriend on thayer.” “really?” “it’s starting to rain.” “really?” “the narragansett police got busted for looking at child pornography – in the police station.” “really?”“i think i need some new shoes.” “really?”

i supposed he thought i was a sell-out to be working as a newspaper reporter. it was too mainstream. he never said it, because he was reluctant to reveal himself, but i sensed his disdain. malakami was ten years younger than me and was a part of that generation which emphasized to everyone that it had given up before it had started. it had dropped out before tuning in. he never said or asked anything about my work. he got me wondering if i was a bigger asshole than i knew i was, not that i could do much about it. i don’t think malakami and his unfriendly slacker friends understood what i was writing. and it seems to me malakami should have known. he’d read my short stories and knew my sensibility. maybe he did know i was accomplishing more than i would have as a slacker, working as a newsroom iconoclast, pushing boundaries and fighting to get stories into print. maybe he didn’t like me chasing corrupt mayors out of town. i expanded the paper’s vocabulary to include words the readers used and appreciated seeing in print. you know, words like “boobs” (barbara eden) and “shit” (norman mailer). i hurt a fascist police chief so bad he traded nine millimeters for .45s and built a moat of silence to keep me out (didn’t work). i had the distinction of being the only reporter dragged into the publisher’s office for a whipping in the last 100 years. i received fan mail and had beautiful stalkers sending perfumed letters and following me to meetings. i won more journalism awards than anyone in the state, awards judged by the maine press association, the arizona press association, and the connecticut press association. these are just the facts. but the publisher didn’t care any more than malakami. i was waging war on his class, his golf buddy who was paying kickbacks to get city contracts. his friends meant more than that during my first year on his paper, circulation went up 30% on my beat. editors said kind things, but to the publisher i was the antichrist. some co-workers who were better telephone operators than writers were jealous, though content in the cowardice that meant job security. they sat at their desks with their noses in their computer screens and their ears to the telephone while i was out in the air with the man on the street – a practice i was bitched-out for countless times. actually, i was bitched-out for hanging with the man in the street for eight years. i nearly lost my job twice because i believed the man in the street knew more than the mayor. newspapers were killing themselves and i felt headed toward extinction.

malakami was the voice of youth and reason in that house. he gained most of his wisdom from comic books. he broke up fast with a sweet, humble and funny, and gorgeous blonde to go out with a self-centered egomaniac who called herself nova. nova came from santa cruz to study sculpture at rhode island school of design. she had a full scholarship. she quickly started a band for herself, called “slippery pork.” malakami was the bass player. nova once asked me “what are your views on art?” she ambushed me with this at 6 a.m. as i was on my way to the toilet. i was not awake and hadn’t noticed her sitting on the kitchen couch. she scared the shit out of me and i nearly threw up on her. malakami stopped coming into my room and avoided me well before i was staring at walls. maybe it was his girlfriend. maybe he was afraid of me in general. maybe he wanted to deny me. i never believed he envied me, but he had an attitude. as artists, we were opposites. he was very controlled, conscious, and obvious, whereas i was barely involved.

once we were on a pabst kick and i bought him a 12-pack before leaving for the weekend. i told him it was for him. when i returned, the 12-pack was still there, untouched. he had to have drunk beer during those two days. the pabst sat for almost a week and then i drank it. within hours, he bought a six of pabst and placed it like a condemnation in the exact same spot in the refrigerator. he didn’t want anything from me. i saw less and less of him. when i got sick, he vanished, then he bought that plane ticket home. i can’t blame him for being afraid now, but at the time i didn’t understand. the truth is a lot of people are afraid of those with an illness, especially mental illness, even people who love what the sick create – which makes them hypocrites.

PEOPLE ARE EASIER TO SEE THROUGH THAN BLINDS AND I HAVE SEEN THROUGH THE INTERSTATE WITH GLASS EYES. PEOPLE ARE EASIER TO JUMP OVER THAN BUILDINGS AND THO I HAVE YET TO LEAP OVER A BUILDING IN ANY NUMBER OF BOUNDS, MY SKELETON IS THE KEY TO EVERY SOUL. MY GIFT IS FINDING LOVE AND EXPOSING ARROGANCE. I CAN MAKE A MAN LOVE ME OR FLEE IN ONE MINUTE. I CAN INSPIRE GENEROSITY AND GENIUS AND SOULS WITH MY EARS.

i considered doctors and hospitals in the yellow pages and then closed the book.

one day i left the house and walked up to college hill. brown university chicks were looking out the windows of cafes. the cars seemed fast and loud. i didn’t like passing people on the sidewalk. i felt them reading me. i wanted to be alone, but i endured the world because i was on a mission. i went into the army-navy store and picked out a down sleeping bag. the guy there asked me where i was going with it and i told him the catskills. he said i would freeze to death. he tried to sell me a warmer bag. i didn’t want it. spring was coming. i wanted the old down one, not the newer synthetic one. i threw it on the fire escape to air out, grabbed a beer and drank down some percocet. i went into my room and closed the door and played my guitar. i chose the 12 books i could live with for the rest of my life, which would go down in a tent in the new york mountains. there was one woman: marguerite duras.

we had a cat named stew who made a night game of sneaking into my room and getting as close to my nose as possible. when my eyes popped open, he’d run - with a copy of balzac’s seraphita close on his tail. stew was my primary source of humor and entertainment. in the morning he would be standing outside my doorway, the line we had agreed upon, trapping me into a game before i made coffee. we had french roast, columbian, sumatra, kona, cabernet, chianti, bordeaux, pabst, bowmore, johnnie walker black, glenlivet, pernod, absolute, tangueray, newcastle, jim beam, and a bowl of percocets and vicadins. we did not have budweiser.

i was writing for the boston globe, the narragansett times, and reuters. i was making enough to pay the rent, put gas in the car and have a car, have a girlfriend, and indulge my weaknesses. which did not mean i could slack because once you’re in, you’re in, and if you stop for a minute, you’re out. i was caught in a never-ending race to produce bird cage liner. i was manic, and i did not feel strong in the head. i was interviewing all manner of humanity, from presidential candidates and actors to the guys lumping fish heads. they were all the same and none of it mattered to me anymore. my thoughts were fractured. i poured booze on the psychic pain and my thinking became scrambled. my way of life was my life and it was failing. a letter came into the paper, critiquing a story. it was hostile and, for the first time in six years, correct. i had written 1,600 stories and had been impervious. i was slipping.

in this third-story flat, stew was reading the tick and malakami was playing his bass before he headed to work at the laundromat. the chick was on the phone. always on the phone. Her social life was competing with my professional life. malakami had argued that we take this chick on to lower our rent. i had argued against it because i knew she would be ignored. when we had found the place, malakami and i were close, partners in a nocturnal cabal, and the chick had really wanted to move in, so i let it go. she didn’t like living with us and i didn’t care. she was a good chick, but she was taking up space with her need to be fucked. eventually she became a lesbian.

i had started back on my horn and was sitting in with a local jazz band. my hearing had become so acute that i started seeing things: i saw the notes when i closed my eyes, c, Eb, f, f#, g, Bb, c , displayed like a map to possibility. notes flashed while i played. i followed them. i had been playing 20 years and this phenomenon changed everything. i was in an altered state, but i was unaware. i saw these visions as a blessing, not a sign of impending hell.

home from a gig, buzzed, i’d find the globe on the machine wanting shit at 10 p.m. we need all you can get on a vietnamese murderer from providence. we want you to go to his house. do you know vietnamese? do you know anyone who speaks vietnamese? how about a professor at brown? oh, and we need it in 45 minutes. i run out the door and track down a street walled in by graffiti and lit up by shattered glass. i find the house the killer had fled from. there are lights on in the kitchen and basement. i knock. i look through the windows. the place is empty. i interview a neighbor walking his rotweiller near the abandoned house. “haven’t seen him in two days.” back home, i call in a description of an empty house and a guy walking his dog – maybe a cop.

NOBODY LOSES HIS MIND, HE LOSES THE ABILITY TO WARD OFF INVASIONS. YOU LOSE SIGHT OF THE MURAL WHILE YOUR HANDS FIGHT THE ABSTRACT INVASION. YOU BECOME A MONSTER AND AN ISLAND. IT IS THE REPLACEMENT OF THE INDIVIDUAL BY THE ALL, A MARTYRED FLIGHT TOWARD THE SOURCE, LOSING ONE LIFE TO BE A THOUSAND.

i had time to work on the short stories i had written in san francisco two years earlier, which was when i first met malakami. then i had been with jess, who was now a year in the past. jess had worked at an insurance company while i stayed home and typed. she made those short stories possible. malakami was a friend of our neighbors’. he visited them one night while jess and i were there. he was with his girlfriend. malakami was dressed sharply in a long black wool coat and did not say a word to jess or i. actually, he did not look at us despite coming through the front door into a living room where there were only four people, his two friends from hawaii and us. he talked to our neighbor, who was sitting on the couch next to me, but did not look at jess or me. they didn’t stay long. my first impression was not good, but i learned he was an artist. jess and i left california and broke up. malakami and his girlfriend broke up and he came east in a tail-spin. our villa spaghetti days began.

jess was now living in newport. i had run into her twice. it was strange to look at her as somebody else’s girl. at an outdoor flea market i watched a new guy demonstrate golf clubs to her. i had never thought of that. one time i saw her and i missed her. we had been through everything together and no other girl would know that journey. the memories seemed wasted without her. i was now with layne, the tall rhode island school of design student with long black hair. layne was a photography major and almost a normal chick. at first, her pedigree and family history seemed to have corrupted her very little. she was irish and she drank well and laughed a lot. her body and her sense of humor made me happy in the beginning. she was also one of the best photographers i had ever met and i brought her out on a story where she compassionately captured peter wolf’s pallor and decay for the world.

jess was now living in newport. i had run into her twice. it was strange to look at her as somebody else’s girl. at an outdoor flea market i watched a new guy demonstrate golf clubs to her. i had never thought of that. one time i saw her and i missed her. we had been through everything together and no other girl would know that journey. the memories seemed wasted without her. i was now with layne, the tall rhode island school of design student with long black hair. layne was a photography major and almost a normal chick. at first, her pedigree and family history seemed to have corrupted her very little. she was irish and she drank well and laughed a lot. her body and her sense of humor made me happy in the beginning. she was also one of the best photographers i had ever met and i brought her out on a story where she compassionately captured peter wolf’s pallor and decay for the world.

HER LONG ARMS AND LEGS MOVED THE BED. UNDER THE SHEETS I WAS RIGID IN THE SUNLIGHT, WATCHING HER SLEEP. SHE CRAWLED ON MY FLOOR, THROUGH MY CLEAN LAUNDRY, LOOKING FOR HER PANTIES, THE SUN BURNING LACE PATTERNS ON THE PINE. IN THE BACK ALLEY, A DALMATIAN NAMED SPOT BARKED AT SATURDAY MORNING GHOSTS. LAYNE’S EYES WERE THE DAWN. HER EYES BLUE LIKE HAVANA, SPECKLED WITH AZTEC GOLD FLAKES. BLUE AND GOLD WHEN SHE OPENED THEM. HER EYES IN THE MORNING SUN, I NEVER WANTED TO LEAVE THEM. WHEN SHE CLOSED THEM, I WONDERED WHAT SHE MEANT. IS IT STILL NIGHT? I WAS ALONE, WATCHING, WAITING. IF SHE WAS BLINKING, I WAS A FOOL. A FOOL, I FELL INTO HER BREASTS. I WAS JUST A MAN IN THE SUMMER OF HIS LIFE, WRITING POEMS ON HER BACK WITH HER BEAUTIFUL FACE IN MY EYES AND HER BLOOD ON MY FINGERS.

layne revealed herself to be very conservative for a liberal democrat. she was a liberal not in favor of proving it: the poor deserved to suffer. i was a-political and didn’t vote, but i knew there were more nobles among the poor and nobody deserved to suffer. layne’s family were millionaires and she had an allowance. she began to live in restaurants and bars. she had been studying art in italy before we met, had lived on wine and bread and simple foods. six months back in america and she was covering herself in bed. she was aware and it seemed to make her eat more richly. i was not nice near the end, but i was losing my grip on niceties. she was naïve in many ways, young and bourgeois. i could not educate fat.