|

Dear Janet:

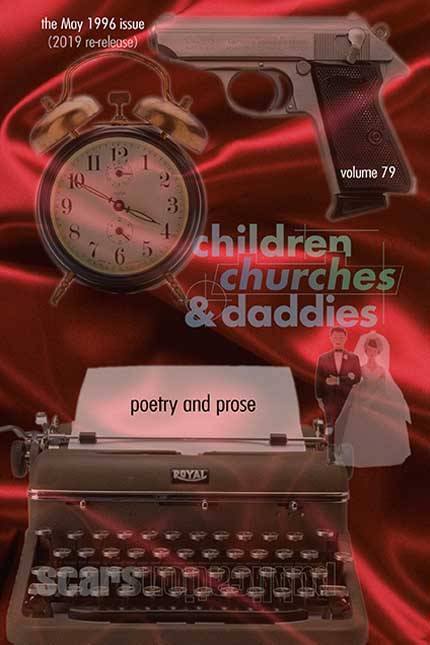

I received Children, Churches and Daddies just the other day, and you were right about the ‘96 issues being HUGE. Actually, I wasn’t expecting something quite that large, but then, I don’t really know what I was expecting either. Anyway, though, I really enjoyed it - not just the poetry, but everything about it, really, especially the articles and letters about various things - it was interesting, too, reading about the origin of the title of your Scars Publications.

With the poetry you included, I really enjoyed the pieces by Alexandria Rand, C Ra McGuirt, Lyn Lifshin, Mark Sonnenfeld (his writing style is so engaging) and Greg Kosmicki. I also liked your poems “i want love” and “dandelions for a passing stranger.”

|

|

by Janet Kuypers

i’m laying here in bed

and i’m looking over at him

he’s sound asleep

perfectly happy

you know, i can’t remember

the last time he’s held me

he has no idea what i’m thinking

he’s perfectly content this way

i decided to spend the rest

of my life with him

he’s my best friend

but i don’t know if he loves me

damnit

i want love

|

|

by Janet Kuypers

I loved my silly red tricycle, the type that every suburban three year old probably had. I would play on my driveway, riding past the evergreens, past the white mailbox... But I’d usually turn around before I rode past the gravel and onto the neighbor’s driveway and ride back toward the security of my own garage. I would sometomes play on the neighbor’s driveway, since it was on a hill. I would scale to the top by their maroon colored garage, navigate my trusted tricycle around by its rusted handlebars, hop on the seat and zoom downhill. But those times were only for when I thought no one was home at their house, and for when I was feeling particularly adventurous.

Once I was riding up and down my own driveway and I saw another little girl walking on the neighbor’s yard. I watched her approach my driveway, walking on the edge of our lawn. I was fascinated by this girl. There was a new face to look at - a girl with long blonde hair, so different from my own. She came from the lawn behind my house and was walking along the side of my driveway, away from my home. I just watched her walk. When she passed me, I looked over to the neighbor’s yard. Our lawn was full of green grass. Theirs was full of dandelions. I rode over to the side of my driveway, got off my tricycle, hopped over the ledge and ran onto the neighbor’s lawn. I picked a dandelion.

I quickly ran back to my tricycle. It patiently waited there, just where I left it... I pedaled fiercely to the end of my driveway, and caught up with that little girl. Still sitting on my

tricycle, I looked up at her until she stopped walking right in front of me. I held up the dandelion to her.

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers, in 3 parts, reading her poetry 10/12/19 at the Georgetown “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library. In part 1, read her poem “Check Your Clock” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, her poem “Other People’s Worlds” from the cc&d v291 7-8/19 book “Of This I am Certain”, then her poem “Queueing in Line and Shaping Your Life” read from the cc&d v292 (Sept.-Oct. 2019 issue) perfect-bound paperback ISBN# book “In The Fall”, both of those last two poems also read from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Know What Planet She’s From” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 2, she read her prose poem “Dandelions for a Passing Stranger” read from the cc&d 2019 reprints of the May 1996 v79 issue book “Poetry and Prose”, then her poem “Ominous Day” from the cc&d v290 May-June 2019 26-year anniversary issue/book “a Rose in the Dark” that also appears in (and is co-read from) her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Etching, Scribbling, Drawing” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 3, she reads her poem “Kind of Like a City” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Zircon, Gemstones, Baubles, and Bling”from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)” (this video was filmed from a Panasonic Lumix 2500 camera, and it was also posted on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram & Tumblr).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers, in 3 parts, reading her poetry 10/12/19 at the Georgetown “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library. In part 1, read her poem “Check Your Clock” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, her poem “Other People’s Worlds” from the cc&d v291 7-8/19 book “Of This I am Certain”, then her poem “Queueing in Line and Shaping Your Life” read from the cc&d v292 (Sept.-Oct. 2019 issue) perfect-bound paperback ISBN# book “In The Fall”, both of those last two poems also read from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Know What Planet She’s From” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 2, she read her prose poem “Dandelions for a Passing Stranger” read from the cc&d 2019 reprints of the May 1996 v79 issue book “Poetry and Prose”, then her poem “Ominous Day” from the cc&d v290 May-June 2019 26-year anniversary issue/book “a Rose in the Dark” that also appears in (and is co-read from) her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Etching, Scribbling, Drawing” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 3, she reads her poem “Kind of Like a City” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Zircon, Gemstones, Baubles, and Bling”from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)” (this video was filmed from a Panasonic Lumix 2500 camera, and it was also posted on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram & Tumblr).

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers, in 3 parts, reading her poetry 10/12/19 at the Georgetown “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library. In part 1, read her poem “Check Your Clock” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, her poem “Other People’s Worlds” from the cc&d v291 7-8/19 book “Of This I am Certain”, then her poem “Queueing in Line and Shaping Your Life” read from the cc&d v292 (Sept.-Oct. 2019 issue) perfect-bound paperback ISBN# book “In The Fall”, both of those last two poems also read from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Know What Planet She’s From” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 2, she read her prose poem “Dandelions for a Passing Stranger” read from the cc&d 2019 reprints of the May 1996 v79 issue book “Poetry and Prose”, then her poem “Ominous Day” from the cc&d v290 May-June 2019 26-year anniversary issue/book “a Rose in the Dark” that also appears in (and is co-read from) her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Etching, Scribbling, Drawing” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 3, she reads her poem “Kind of Like a City” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Zircon, Gemstones, Baubles, and Bling”from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)” (this video was filmed from a Panasonic Lumix T56 camera, and it was also posted on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram & Tumblr).

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers, in 3 parts, reading her poetry 10/12/19 at the Georgetown “Poetry Aloud” open mic at the Georgetown Public Library. In part 1, read her poem “Check Your Clock” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, her poem “Other People’s Worlds” from the cc&d v291 7-8/19 book “Of This I am Certain”, then her poem “Queueing in Line and Shaping Your Life” read from the cc&d v292 (Sept.-Oct. 2019 issue) perfect-bound paperback ISBN# book “In The Fall”, both of those last two poems also read from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Know What Planet She’s From” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 2, she read her prose poem “Dandelions for a Passing Stranger” read from the cc&d 2019 reprints of the May 1996 v79 issue book “Poetry and Prose”, then her poem “Ominous Day” from the cc&d v290 May-June 2019 26-year anniversary issue/book “a Rose in the Dark” that also appears in (and is co-read from) her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Etching, Scribbling, Drawing” from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)”. In part 3, she reads her poem “Kind of Like a City” from her poetry book “(pheromones) haiku, Instagram, Twitter, and poetry”, then her poem “Zircon, Gemstones, Baubles, and Bling”from her poetry book “Every Event of the Year (Volume one: January-June)” (this video was filmed from a Panasonic Lumix T56 camera, and it was also posted on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram & Tumblr).

|

|

I thought “crazy” and “philosophy monthly” were very good, too, and I loved that title “breast cancer in her coffee.” Well, maybe “loved” is too strong a word to use, but it was really a great title.

Thanks again for the great issue of cc+d!

- Joseph Verrilli

Following is the original written piece that prompted the name “Scars publications and Design”:

|

|

by Janet Kuypers

Like when the Grossman’s German shepherd bit the inside of my knee. I was babysitting two girls and a dog named “Rosco.” I remember being pushed to the floor by the dog, I was on my back, kicking, as this dog was gnawing on my leg, and I remember thinking, “I can’t believe a dog named Rosco is attacking me.” And I was thinking that I had to be strong for those two little girls, who were watching it all. I couldn’t cry.

Or when I stepped off Scott’s motorcycle at 2:00 a.m. and burned my calf on the exhaust pipe. I was drunk when he was driving and I was careless when I swung my leg over the back. It didn’t even hurt when I did it, but the next day it blistered and peeled; it looked inhuman. I had to bandage it for weeks. It hurt like hell.

When I was little, roller skating in my driveway, and I fell. My parents yelled at me, “Did you crack the sidewalk?”

When I was kissing someone, and I scraped my right knee against the wall. Or maybe it was the carpet. When someone asks me what that scar is from, I tell them I fell.

Or when I was riding my bicycle and I fell when my front wheel skidded in the gravel. I had to walk home. Blood was dripping from my elbow to my wrist; I remember thinking that the blood looked thick, but that nothing hurt. I sat on the toilet seat cover while my sister cleaned me up. It was a small bathroom. I felt like the walls could have fallen in on me at any time. Years later, and I can still see the dirt under my skin on my elbows.

Or when I was five years old and my dad called me an ass-hole because I made a mess in the living room. I didn’t.

Like when I scratched my chin when I had the chicken pox.

|

letter in response to poems, including

by Janet Kuypers

my phone rang earlier today

and I picked it up and said “hello”

and a man on the other end said,

Is this Janet Kuypers?

and I said, “Yes, it is, may I ask

who is calling?”

and he said, Yeah, hi, this is

George Washington, and I’m sitting here

with Jefferson and we wanted to

tell you a few things. And I said

“Why me?” And he said Excuse me,

I believe I said I was the one

that wanted to do the talking.

God, that’s the problem with

Americans nowadays. They’re so

damn rude. And I said, “You know,

you really didn’t have to use

language like that,” and he said,

Oh, I’m sorry, it’s just I’ve been

dead so long, I lose all control

of my manners. Well, anyway, we just

wanted to tell you some stuff. Now,

you know that we really didn’t have

much of an idea of what we were

doing when we were starting up

this country here, we didn’t have

much experience in creating

bodies of power, so I could understand

how our Constitution could be

misconstrued

and then he put in a dramatic pause

and said,

but when we said people had

a right to bear arms

we meant to protect themselves

from a government gone wrong

and not so you could kill

and innocent person

for twenty dollars cash

and when we said freedom of

religion we included the separation

of church and state because freedom

of religion could also mean freedom

from religion

and when we said freedom of speech

we had no idea you’d be

burning a flag

or painting pictures of Christ

doused in urine

or photographing people with

whips up their respective anatomies

but hell, I guess we’ve got to

grin and bear it

because if we ban that

the next thing they’ll ban is books

and we can’t have that

and I said, “But there are schools

that have books banned, George.”

And he said Oh.

|

Janet,

George called you too, huh? Damn if he wasn’t cussing up a storm about the recent government shutdowns. He kept saying that only the People were supposed to be doing stuff like that, not the government itself. It did no good to remind him that people generally know very little and could not care less about the inner workings of government machinery. All he did was go on some tangent about how the priniciple of government is based (or supposed to be based) on the idea that “it” represents the People through representation, and that through the democratic process justice and goodness is guaranteed to pr

evail, and the People will prosper as a result. He reminded me of what Confucius said:

Equity is the treasure of the states.

And I told him that I never heard of such a thing. This made him really upset. “Probably got banned in one of those books Janet was talking about,” he muttered glumly. What a strange duck he was! The idea that a People’s Representative would seek, during the term of his or her office, to do more harm than good was completely and utterly unfathomable to him. Anyway, Janet, if ol’ Georgie should ever call you again, see if you can get his number. I have a feeling that we’re not the only ones who would like to have a little chat with the guy whose face is on a billion dollar bills.

Re “people’s rights misunderstood”:

|

|

by Janet Kuypers

I had a dream the other night

I was walking down the street in the city

and a man came up to me

a skinny man, he lost his hair

and he walked right up to me

and told me no one cares anymore

and he took my hand

and asked me to care about him

“I’m not supposed to be like this” he said

“I’m not homeless, you know

I have AIDS”

and I wanted to tell him that

someone did care,

that he didn’t have to die alone,

but you know how sometimes

you can’t do things in your dream

no matter how hard you try,

well, my mouth was open, wide open,

but no words were coming out

you know, I’m afraid to go to sleep tonight

I’m afraid that a pregnant woman

will come up to me

and ask me for a hanger

and I’ll tell her there has to be another way

and she’ll say this is the way she chooses

I’m afraid a woman will come up to me

and tell me she doesn’t want to live

because she’s just been raped

and her world doesn’t make sense anymore

and I’ll tell her that she can make it

that one in three women are raped in their lifetime

and they all make it

and besides, the world doesn’t make sense

to anyone

and she’ll say that doesn’t make me

feel any better

and I’m afraid that I won’t be able to

walk down that city street again

without it looking like a Quentin Tarentino movie

where everyone is pointing guns at each other

ys, Mr. NRA

you are right

I feel so much safer

knowing everyone out there has a gun

that there are more gun shops than gas stations

and that everyone is so willing

to do the killing

|

(from letter)

You know, it has often occurred to me that if there were less gunshots fired on the Big Screen and more acts of altruism shown, we might not have less crime (see bad economic policy/economic disparity versus action films as true cause of violent crime) but we would at least have examples of human beings whose actions truly merit admiration. In my opinion, “Pulp Fiction” wasn’t a bad movie at all. Tarentino knows how to keep things interesting. But perhaps IF there were more films such as Akira Kurosawa’s “Red Beard” there wouldn’t be nearly as much interest in depravity (however entertaining it is to watch) as there would be in overcoming one’s faults in order to become a better person...which benefits society as a whole where individuals are concerned.

Re “Child labor”:

|

|

by Janet Kuypers

i heard a story today

about a little boy

one of many who was enslaved

by his country

in child labor

in this case

he was working

for a carpet factory

he managed to escape

he told his story

to the world

he was a hero at ten

put the people from the factory

held a grudge

and today i heard

that the little boy

was shot and killed

on the street

he was twelve

and eugene complains to me

when i buy shoes

that are made in china

now i have to think

did somebody

have to die for these

will somebody have to die

for these

|

(from letter)

Well said. I know a few kids right here in Minneapolis who work twelve hour shift seven days a week. For less than seven dollars an hour. At a factory which makes junk mail and newspaper advertisements and inserts. Some of these kids are fresh out of school (I worked there for three months as a janitor and got to know them a bit) whose eighteen-year-old minds are fresh and easily aquire new ideas. It is my belief that any of them, in another time and place, could just as easily have been Henry David Thoreaus or Einsteins or Ghengis Khans for that matter, but instead they stand in front of machines for half their lives helping their employers and various other Big Players make their wallets fatter, while these kids struggle to pay the bills.

While talking to an older fellow named Ron about it, he simply said life is not fair...and that people are wrong to call such operations “profiteering.” He said that’s “commie talk,” that here in America it’s called Entrepreneurship, or Capitalism.

- Neil Cunningham

|

the secret side of the fence

by Catharine Wright

“Come with me, Ruby, let’s go for a ride,” Ruby’s father said one day after school. It was spring, and he was in a good mood.

“Where?” Ruby said.

“Never mind.” He jingled his keys in his pocket. “Just come. Put your coat on.”

She didn’t move. Last time he’d taken her somewhere he left her with some women in a house with an old fashioned clothes washer which crushed children’s fingers if they got near it. One of the women had offered her a homemade donut. It was small and greasy and Ruby wanted it so bad her mouth filled with spit. But she’d taken her head. She didn’t know why she was there or where her father was. The women wore black and smelled like steam.

Her father looked at Ruby, surprised. “Don’t you want to go for a ride?”

She never got to be with him alone, so she put her coat on.

****

They stopped at a gas station with a broken sign. “Have you met Mr. Phelps?” he said as they got out of the car. “You know Mrs. Phelps and old Mrs. Phelps. The two ladies down there?” He pointed down the hill towards the house with the crusher washing machine. “This is old Mrs. Phelps’ son. Hello! Hello!” He pushed open a dirty door.

First a man’s work boots, then his green legs o

ozed out from under a car. He smiled slowly at Ruby’s father.

Her father touched Ruby. “The youngest. Hey-how’s your mother? This one’s been there.” He rapped her on the head with his finger.

Mr. Phelps said, “pre-e-tty good,” and smiled like he was getting a lot of attention. Then he rummaged for some old pipes and showed them to ruby’s father. They didn’t fit together and had big rust spots. Ruby’s father shrugged and said sadly, “Let ‘em go.”

Back in the car her father said: “That’s stop number one. Now we go to the heating plant. Have I ever taken you to the heating plant?”

“No.” She imagined a big, warm plant growing in water.

He swung the car down a hill and parked by a gray cement building, and a man covered with black powder came out.

“Hey-” Her father shook the man’s hand and put his hand on Ruby’s head. “Have you met the youngest?”

The man had sad eyes. He put out a sooty hand and Ruby slowly put hers in it. After he shook it she looked at her hand.

“Do you know what that is?” her father said.

“No.”

“That’s what Walter uses to keep the school warm. It’s coal. Did you know that?”

Then she realized that the tall smokestack she saw from her house came from this building and heated the school. “How come I never knew that?” They laughed. They talked about coal and oil and people who didn’t know enough. Ruby waited.

“Are we going home now?” she asked back in the car.

“We’re only half done. Aren’t you having fun?” He looked over in surprise. “I tell you what. One more stop and we’ll go home.”

They parked in front of a big flag and her father winked at her and inside he whisked her through a swinging door.

She was sure they shouldn’t be there. He always did things he wasn’t supposed to do. She edged up against the swinging door while he talked to some women behind a fence that looked like a bank. Her father was on the secret side of the fence. The women were laughing and her father acted like he was telling them something scandalous. Ruby hung by the door and wished he’d hurry up before they were caught. But he turned and yelled, “Ruby! What are you doing over there? Come meet these nice women.”

Everyone behind the fence and in front of it looked at Ruby. She edged over. A woman touched her hair and said, “Aren’t you lucky to have hair like your Daddy.”

Outside, she told him he wasn’t supposed to go through those doors.

He laughed. “Ruby! I’ve been visiting these women for years. They’re my friends. Can’t you tell?”

She was silent.

He started up the car. “Don’t you see I make it a point to know people? Some people go around like this.” He put a finger on his nose and pushed it up so he looked like a pig.

She smiled.

“Do you know what I mean? It means someone’s a snob. But I don’t like snobs. You can go anywhere in this town, Ruby, and tell people who you are, and I bet they’ll know you. You have to reach out, you can’t live in a cocoon. Your mother doesn’t always realize that but it’s true.”

Her father started singing. Ruby relaxed and felt the car safe and rumbling around her. She felt her father’s big, singing presence, and watched the dorms and fields go slowly by. Catnip mountain came into view in her window.

Her father must be right. She shouldn’t have worried. She turned to look at him, at his big face and red hair. He was thinking about her mother too. “She’s not a snob,” Ruby said.

He looked at her. “You don’t think so?”

“No,” Ruby said, “not exactly.”

He seemed to be listening, to be thinking. “No,” he agreed, “she’s not a snob. That’s not it.”

****

Ruby’s mother’s long, pale hands moved across the pages of books at night, and her voice took on the low shapes of trolls and wolves. When Ruby was upset, her mother said, “I know, I know”, with deep, awful meaning.

On her seventh birthday her mother took Ruby to a toy store. Ruby was astonished to see so many toys in one place. She chose an enormous bouncing ball with a plastic ring around it you jumped on. It was the first time she’d picked out a toy like that and she clutched the box to her chest.

They went to a diner for lunch. She had never been out to lunch with her mother. They sat in a soft, sticky booth eating french fries and cheese sandwiches. Then her mother said they were doing something even more special.

They drove to a tar papered building that was dark inside and sat in a row of chairs. It reminded Ruby of waiting for her mother while she measured the arms and legs of the reform boys at the school for costumes. She slouched in her seat.

When the curtains lifted, a room of straw burst out with a girl in a red dress talking to an old man, and the girl cried when he left. Then a little man darted in. Ruby forgot about the hard seats.

When the play ended, she was stunned to find herself in a dark room full of people and chairs. As they walked out, her mother hummed. Ruby made a noise in her throat. Her mother said, “Did you like the play?”

Ruby burst into tears.

”What’s the matter? Did it scare you?”

Ruby sobbed.

“Ruby, tell me, please.”

She couldn’t stop. She waved her arms to try and tell her mother.

Her mother smiled. “Oh, I know,” she said.

On the way home Ruby asked whey they’d never gone there before.

“They were visiting actors-and actresses,” her mother explained. “They travel around the country and put plays on in different towns.”

“They’re leaving””

“They have to. Other people want to see the p

The were the most special, wonderful people in the whole world, and Ruby wished she could make them stay. But she understood other people wanted to see the play. “How come more people don’t do that? What those actors do?”

“I was part of a traveling theater once,” her mother said dreamily. “Before I was married. But your Aunt Melanie was the one who did it for years. She directed her own company. She was probably the first woman to do that. I remember my parents being very upset that she was gallivanting around the country with no money, sleeping on trains. She got sick in Louisiana, from exhaustion I think, and my father went and got her.” Her mother paused. “She gave it up after that.” Her voice got a familiar tightness. “It’s too bad.”

“I want to do that,” Ruby said quickly.

Her mother turned to her. “You can do whatever you want. You don’t have to do something practical, no matter what your father says. You should do something you love. That feeds the imagination.” Her fingers gripped the steering wheel. Her shoulders tensed.

Ruby stared across the long car seat at her. She studied her mother’s pale face and dark hair against a wide, moving landscape.

****

After that, Ruby hung around the theater at the reform school. She made a nest in the seats with her books and toys.

One boy offered to read her a story, and then he played tag with her in the back lobby. After that Ruby looked for him, and they played between the acts when he came on.

“Don’t go far,” her mother warned. She was busy sewing and measuring, collecting props and gluing broken ones.

The boy asked Ruby to play hide and seek in the fieldhouse on the other side of campus. Her father had forbidden her to go there because he said it was just for the boys. Ruby thought it was really because the school hadn’t used his plans for building it. She and her friend Kate went there on weekends, and no one had said anything to them. So she rode her bike there. The gym was empty and they played hide and seek. When it was the boy’s turn, Ruby couldn’t find him.

He motioned to her from the women’s bathroom. He waved her in and then locked the door. “I have to ask you something, Ruby.” He knelt down. “I’m studying to become a doctor and I noticed something might be wrong with you. I want to help you. Will you let me help you?”

She took a step back. Her parents had told her not to play with the boys. “What’s wrong with me?”

“I’m not sure, I need to check. We’ll stop if you say no.” He looked concerned.

“Are you really a doctor?” She thought the boys were just students.

“I will be. I’m almost one.”

She was worried something was wrong with her. She took off her clothes like he asked and was surprised when he took off his clothes. “Why are you taking off your clothes?”

“I need to in order to check you. Could you lay down on the floor? On your back?”

She lay down. He appeared over her like he was doing push-ups, and his big red penis touched her leg. She froze. He said, “I need to put this inside you, and I’m going to pee just a little bit.”

She eyed it. It was huge. “I don’t want to do this.” Her voice shook. “I want to go.”

“It’ll just take a minute. It’s for you, I’m worried about you.”

“I want to go,” she said, louder.

It took forever to put her clothes on.

He said, dressing quickly, “It’s alright, I think you’re okay.”

He unlocked the bathroom door and she ran for the outdoors and jumped on her bike and pedaled as fast as she could, knowing something awful had happened.

He pulled up on his bike, next to her. “You won’t tell anyone will you? We’re still friends, aren’t we?”

She pedaled so hard her lungs hurt. But she couldn’t outpedal him. He was talking, begging. She didn’t look at him.

She ran to find her mother and her mother took her upstairs and sat her down on her bed. “What did he do?”

Ruby squirmed. She wasn’t used to having her mother look at her so closely. She looked down at the bedspread. “He asked me if he could pee-inside me.”

Her mother stiffened.

Her brother Toby stomped up the stairs with a bunch of boys. “Mom? MOM!!”

Ruby looked at Toby in the door, but her mother didn’t seem to hear him.

“Mom?” he said.

Her mother’s body was rigid. Without looking at Toby she said, “What? Can’t you see we’re talking?”

“He has a question,” Ruby said. She felt sorry for him. All his friends were standing behind him looking at their mother.

“I just want to know-”

“I don’t know!” their mother cried. “Do whatever you want!”

Ruby looked down at the floor as the boys went quiet and shuffled off.

Her mother turned her back to her. “So tell me what he did.”

Ruby swallowed. “He said there was something wrong with me and he could make it better, but when he-he-”

“He what?”

“He asked me to lie on the floor, but it was cold and when he got near me I-” Her mother’s tension overwhelmed her.

“You’ve got to tell me Ruby. Tell me what he did.”

“I wanted to go home.”

“Did he do anything?”

“He wanted to pee in me but . . . I didn’t want him to.”

“But did he?”

“No.”

“Are you sure? Did he touch you?”

“He didn’t touch me. He let me go home.”

Her mother sagged against the wall. “Oh thank God, Oh thank God.”

****

That night her mother dressed her in a dress and told her that the boy who they thought had taken her into the bathroom was coming over. Ruby was supposed to tell her if it was

Ruby waited with her mother in the kitchen until her father came home. She heard voices in the living room. “Now go out and look at him,” her mother said. She pushed Ruby towards the door

There was a man in a black suit at the far end of the living room. His hair was slicked down. He didn’t look up, and she couldn’t see his face clearly across the room.

She went back to her mother and said, “I can’t tell if it’s him.”

“What do you mean you can’t tell? Go back out and look again. This is important, Ruby, you have to.”

“I can’t just stand there,” Ruby whimpered.

“Pick out a book. Sit down to read, and just glance up at him.”

It felt strange to Ruby to look at a book while the boy who had almost peed in her was in the room. It was strange to pretend that nothing had happened. It felt wrong to wear a party dress. It didn’t make sense that he was in a suit with his hair slicked back. But she walked back out to the living room and took a book off the shelf. She walked stiffly in her dress to a chair and opened the book, and peeked over at the man. She still couldn’t tell if it was him.

She went back in to her mother. “I think that’s him.”

The next day her mot

her said that he was expelled from school. “He did a very bad thing. He shouldn’t have tried to touch you. Don’t you ever let one of the boys-any boy or man-touch you.”

“But how do you know it was him?” Ruby felt anxious about that. Her mother was good with costumes, but when it came to finding out who someone really was, Ruby wasn’t sure she trusted her.

“He confessed,” her mother said.

Ruby imagined a meeting in which the boy was surrounded by men from the school, questioning him. She felt sorry for him. She felt relieved.

What happened to her made waves at the school, little ripples that came back to Ruby, disguised.

Her friends, Drew and Kate, whose parents were teachers, said they weren’t allowed out anymore without a grown up. Her own parents whispered at night and stopped when Ruby or her brothers walked into the room. Her bother Abe said they were thinking of quitting their jobs and moving, all because of Ruby. He said he’d heard them talking about it.

Ruby wondered what they said. No one said anything to her. She wondered if they ought to tell her what to think about it all. She wondered it they told her brothers her mother was a snob. She wondered if her father knew her mother wanted to be a traveling actress.

No one said.

|

from a distance, so manly

by David McKenna

It doesn’t take me long to acquire a habit. Just ask my drug-dealing friends, or either of my ex-wives. Don’t ask Gianna, the Italian girl in the rowhouse across from the track where I run. She might not know who you’re talking about, even if you tell her Bertram says hi.

For two weeks I flirted with her through the chain-link fence that separates the football field, and the six-lane track that surrounds it, from the driveway behind her parents’ home. On Friday I coaxed her down from her second-floor deck after my five-mile run. We walked the gravel ellipse together, moving counterclockwise like the Gang of Four and the other regulars, until Gianna tired of the monotony and took her leave.

“My friends like this track, but I skeeve,” she said, using a South Philadelphia term that indicates revulsion. Three years here after banishment from an elite college in Vermont, and I’m still learning how the locals tawk.

“It makes my shoes dirty,” she explained.

For the next two days, her deck was empty and my mood foul. I was sorry I’d seen her, and sorrier we’d spoken. I’d started using the track only a month ago, after realizing my 40-year-old legs could no longer endure the stress of running the streets. Now Gianna had spoiled my routine. It wasn’t complete without her.

Bear with me. This isn’t one of those agonizing unrequited lust stories. I like women, or girls - whatever they choose to call themselves - so long as they’re young or pretty, and sometimes when they’re neither. But I don’t stalk or even linger where I’m not wanted, except to make absolutely sure I can’t be of service.

Three weeks of 90-degree heat had stretched well into September, but today the seasons were slugging it out. The new weather suited my mood. A chill wind pushed dark clouds around and kicked up trash under the bleachers. A strong sun peeked through as I sped down the straightaway between the seats and the sidelines.

The great daily trek was in full swing. Joggers and walkers of all ages and sizes - alone, in pairs, in groups - entered through the gate behind the bleachers, circled the quarter-mile track to their hearts’ content, and left the herd when the mood seized them. I looked up and breathed deep as I ran, trying to burn off the feeling of thwarted expectation that always gets me into trouble. The sky was a river running between the clouds. When I lowered my head, the complexion of the day changed.

There was Gianna on her back in a white G-string bikini, with everything she has smiling up at the sun. I reached the point closest to her deck, where the track loops behind the visiting high school team’s goal post, and shouted what had become my standard greeting.

“Gianna, how ‘bout a gelato?”

A coffee house three blocks from the field sells several flavors of Italian ice cream, though they don’t stock chocolate, Gianna’s favorite when she vacations in Calabria.

“Don’t tempt me with that shit, Bernie,” she said, shifting in her padded beach chair long enough to acknowledge me in her usual inaccurate fashion. “I’m trying to lose weight.”

Like many South Philly girls of a certain type, Gianna seems sexier when seen and not heard. To overly refined outsiders, she might not seem sexy at all. To one such as I, exiled from an enclave of pastoral privilege, she is wildness personified.

“Run with me,” I said, cantering sideways to address her directly.

South Philly makes me feel like Fletcher Christian on Tahiti, or Lord Byron in Italy, after his wife divorced him and English society pooh-poohed him for romancing his half-sist

er.

I thought of Teresa, teenaged wife of the 60-year-old count of Ravenna. Byron’s liaison with her pissed off the Pope. A hot number, lost in history. The roving poet must have caught a glimmer of himself in her. Was her profile Byronic, or merely her soul?

“Come on, run,” I persisted, passing the apex of the loop. “Then you can reward yourself for burning off all those calories.”

“Ha,” Gianna scoffed. “Then I put the calories back on, and I look like a blob. Didja think of that, Bernie?”

“It’s Bertram. Bert will do.”

OK, the Teresa comparison is a stretch, but I’ve come to appreciate Gianna’s contrasts. A sweet bird of youth flapping against the weight of toxic paints and powders, her verbal coarseness a jarring counterpoint to radiantly dark skin, brilliant teeth, and a crown of curls so black it shines purple in the sun.

“You look like that babe in Wayne’s World,” I suggested, running backwards now as I moved away from her. “You could star in an exercise video.”

“If I took 10 pounds off my ass,” Gianna shouted before turning her face toward the peek-a-boo sun. It’s a wonder she tans through the foundation, eye makeup and other junk that, despite her best efforts, fails to spoil her looks.

I turned to resume my forward stride and almost ran into the Gang of Four, immersed in their five-mile fast walk. They didn’t seem to notice my nimble last-minute side-step.

“The guy’s no Santa Claus,” said Armond, the loudest, a bow-legged fellow who wears black elastic knee braces. “You can bet he’s gonna make a ton of money.”

All four retirees are about 5-foot-6 and overweight. Their routine involves a current events recap that focuses on disease and/or sports. Mine involves guessing which news item they’re discussing as I overhear a snippet of conversation while running past them.

“The other guy’s no slouch either,” another of the gang chimed in. “He knows Dee-ahn is the missing link.”

Their voices faded, but I’d heard enough. The lubricious owner of a professional football team has pooled resources with the crafty king of a sneaker company to buy the services of a famously flamboyant defensive back. Now the other NFL teams don’t have a prayer.

The loop at the home team’s end of the field swung me back toward Gianna. I passed Rocco, the depressed school bus driver, holding a leash attached to a black Rottweiler. Rocco is built like an upright version of his dog. Stocky, but much shorter than I.

From a distance I look like a white Ken Norton, thanks to the weight-lifting. Norton was a bad dude in his prime. Up close I’m even more impressive. A sensitively brutish aspect that’s never out of style. Sulky mouth, strong nose and sky-blue eyes that can burn a hole in the hardest of hearts. Byron with both feet intact. I look a decade younger than I am.

“Yo Rocco,” I said. “How are those kids treating you?”

Some months ago Rocco found God and jogging, in that order, and banished the invisible demon who’d been urging him to drive his crowded bus through the front door of a fast-food franchise on Broad Street. Or so he told me last week.

“Same as usual, Bert,” he said. “It’s in the Lord’s hands now.”

As were my chances of breaking Gianna’s spell. This time around she was on her belly with her halter strap unhooked. The strip of newly exposed flesh suggested hazelnut on almond. A scoop of hazelnut gelato is especially sweet, like something that dropped off an ice cream tree in heaven.

“What do you do when the sun goes down, Gianna?” I shouted, feeling rash. “Where can I buy you a drink?”

“Maui,” she answered, referring not to the island but to the garish dance club on the riverfront. “My friend’s taking me to Maui tonight in her new Grand Am.”

Gianna mentions plenty of friends, none by name. One friend knows a mobster’s apprentice who drives a Jaguar and tosses $20 tips at bartenders. Another dances in a cable TV commercial for an expensive go-go joint as patrons chant “I like it, I like it.” Gianna’s espresso eyes shine when she tells these stories. Conspicuous spending impresses her even more than well-defined muscles.

“Afterwards, we’ll eat at Alexandria,” I said, referring to a trendy restaurant across from the nightclub. “You like Alexandria?”

Her smile was beatific. Girls at the state college where I teach these days flash the same smile when I rattle off an immortal rhyme: For the sword outwears its sheath/And the soul wears out the breast/And the heart must pause to breathe/And love itself to rest. They smile, I think, at the contrast between my lively demeanor and Byron’s weary words, at the gulf between Byron the legend and Byron the man, at the degree to which the potency of a legend depends on its distance from so-called fact. Or maybe they’re just happy to see me.

“Do I like it?” Gianna asked as I ran in place. “That’s like asking do I like a full-body massage and Jacuzzi.”

It was settled. Drinks, dinner, dancing. Then home to my apartment, if all went well. Or to a hotel near the airport, or a motel in Jersey. It would be

hours before we got there, wherever it was, judging by what she’d told me about her socializing, and by my experience, from which I’ve gleaned the following data:

Gianna and her ilk are obsessed with teeth and skin and clothes. They are meticulous toenail painters, zealous patrons of hair and tanning salons, compulsive users of deodorants and depilatories. They expect to be wined and dined, served and serviced, and woe onto him who fails to pick up the check.

On the other hand, they are lusty and will fuck you into next week if you bring condoms and pamper them as lavishly as their daddies do; if you drive, buy the drinks, reserve the table, leave the tips, and present them with expensive tokens of esteem. Even better if you make occasional rude jokes about their appearance and manners, to signal you’re not the sort of simpering romantic who’ll do anything to get laid. And sometimes they’ll stun you with a sweet remark or involuntary moan at that moment when passion most fully supercedes reason, the only moment that reveals anything about anybody.

None of which mattered to my fellow exercisers, who ambulated ‘round and ‘round, acting out a rite with no apparent meaning. The wind dragging a plastic bag across the gravel sounded like water sloshing down a drain. The sun was a white hole in a black sky. I was on the verge of the dreamtime stage of my run, my only relief from thoughts of sex and death, when a soccer ball rolled off the grassy field and onto the track.

“Wait, I’ll pass it to you,” I said to a 7- or 8-year-old boy who was chasing the ball. I stopped it dead with my left foot, squared off to fake a kick downfield with my right, then stepped past and kicked it sideways to him with my left.

“How’d you do that?” the boy shouted, picking the ball up as I resumed jogging.

“Practice, kid,” I said over my shoulder. “Everything worth doing takes practice.”

What crap. It’s an easy move, as the kid will realize when someone takes a minute to show him. But he and his friends were impressed, watching from a distance. He reminded me of my eldest son, who thinks I’m of hell of a guy, despite what he hears from his mom, Madame Pinstripes. I rarely see him since she became a corporate stooge in Delaware and moved in with some pigeon-toed twerp who wouldn’t know a soccer ball from a sack of spuds.

Gianna saw me handle the ball - I looked to make sure - but she was gone when I glanced up again. The next time around, a red Grand Am was parked under her deck. Her friend, I assumed.

Just as well, I thought, noticing a tall runner in a black spandex suit under a white sleeveless jersey jog down the driveway to the gate near the bleachers, at a pace even with mine. The runner proceeded along the ribbon of concrete that borders the outside of the track. I licked my lips, tasted the salt, and felt an immediate attraction, followed by a stab of doubt. Boy or girl?

I lengthened my stride and gained ground by hugging the low curb that divides the track from the field. The mystery runner showed the elegance of a natural athlete. Long legs and arms, a deceptively fluid stride that made quickness look easy. She - I hoped it was a she - had hair as short and curly as mine, exposing the nape of a long, dark neck.

But she looked manly from a distance. I don’t know how else to say it. Most women, and some men, run mostly with their lower bodies, because they have low centers of gravity and little power up top. This one, you could tell, had equal strength in shoulders and legs, and the sort of resolute cool that indicates great stamina. She/he reminded me of me.

Now the Gang of Four was between us, obstructing my view while discussing their favorite topic, prostate cancer. Sunshine swept the field from directly ahead. Even from 40 yards, it was impossible to tell whether the runner’s baggy jersey concealed breasts.

Armond was saying, “My son thinks I’m bored, he wants me to find a girlfriend. I said, ‘And do what with her, you stupid fuck?’ Part of me ain’t screwed on no more.”

The others hectored Armond for his sour attitude. “Sex ain’t all it’s cracked up to be,” one of them said. “Get your rocks off these days, it might cost you more than you bargained for.”

I passed them hurriedly, gratefully, and edged forward till I was almost even with the runner whose perfect form was so arousingly familiar.

Just ahead of the Gang of Four were Rocco and his dog again, and then the Suspended Octogenarian, proceeding with stiff-legged precision in his usual ensemble: white sneakers and T-shirt with blue dress pants held chest-high by red braces. He smiles at women the same way I’d look at family pictures in an old photo album.

I picked up the pace to get a closer look at the mystery runner. Even before I descried the outline of firm little breasts, I’d compiled enough sensory data - a down-turned hand, a dainty cough, a slight flutter of the feet before they touched the ground - to conclude with some confidence that yes, thank God, my twin was a woman.

I pulled up beside her and said, “Jogging on concrete is bad for you.” She knew jogging was the furthest thing from my mind, I could tell by her grin.

“Everything is bad for you,” she said, turning her head to eye me calmly, as if she’d expected me. “I do what feels good.”

She was Mediterranean-looking and definitely female, about 10 years younger than I, with a slight, clipped accent and an apparent tendency to overdress when she ran. But the similarities were striking: the hair and high cheekbones and long stride, the pleasantly ironic style of speech, the sulky countenance dissolving to a double-dare-you grin. It was eerie, flirting with myself. The ultimate kick.

“Well, you look good,” I said in typically straightforward fashion. “You could star in an exercise video.”

This time I meant it. Gianna, bless her, will never have good form or keep off the extra weight for long, any more than I’ll ever teach physics or have an enduring high-fidelity relationship. Her charm is fugacious. But the tall one - she said her name was Ronnie - is my ideal, or this month’s version of it. A strong, clear-eyed creature whose beauty is enigmatic precisely because it’s so modestly functional. She laughs like one who enjoys the act of laughing even more than the jokes that inspire it. Her face in repose is sad and calls to mind a garden locked behind high stone walls.

Maybe I assume too much, but that’s my style. A glimpse, a whiff, a taste of new territory and I throw my compass overboard. Already I was guessing the facial expressions Ronnie makes while climaxing, and whether she cries out or holds steady and purrs with her full lips clamped shut. And I meant to find out, instead of regretting not making love to her if, God forbid, I live to be an old capon like Armond.

“This will probably sound sexist,” I said, “You move like a man, but without seeming unfeminine.”

“Naive, not sexist,” she replied. “Define feminine.”

Again the ironically friendly glance, as if she was daring me to share a joke.

“Graceful, sensitive,” I said, undaunted by the semantic quagmire up ahead. “Not necessarily passive, but sere

ne.”

“Men can’t have those qualities?” she countered.

Fortunately, I was used to this sort of discussion. It’s an occupational hazard at colleges, especially if you run afoul of the sob sisters and saber-rattling viragoes in Women’s Studies, most of whom personify sin as a promiscuous heterosexual male. Pardon the hyperbole, but sexually stunted female academics get my back up and have stretched my tolerance to the limit.

“You are aware, fraulein, each man and woman is a mix of masculine and feminine,” I said. I was on my sixth mile and tiring. Ronnie’s handsome face was inscrutable. Eye contact with her was like a tennis match. Every time I served the ball, she politely sent it screaming back at my head. She was indeed my twin.

“Your mix seems more balanced than most people’s,” I said, dropping the accent. “It seems close to mine.”

I felt false, but what could I say? I’m an addict, Ronnie. When I need babying, be my mama. When I need sex, be my lover. When I need both, wrap yourself around me and don’t talk.

Or I could be her daddy - actually, her older, lusty brother - though that sort of thing is what started the neo-Puritan watchdogs barking at the prestigious citadel of learning where I used to wow future schoolmarms with my looks and erudition. Ronnie, at least, was no schoolgirl.

“Am I more balanced than Gianna?” she asked casually.

“She’s way out of balance,” I replied, without showing the slightest surprise at the mention of Gianna’s name.

“She looks like a goddess and talks like a Teamster.” I explained. “Passive until she gets riled, but no more sensitive than that goal post over there. An interesting mix maybe, but not for long.”

“For as long as it takes to fuck her,” Ronnie said, as brightly as Katherine Hepburn would have if they’d used the “f” word in The Philadelphia Story. “Or should I say fuck her over?”

The clouds parted slightly and a single ray of milky sunshine beamed on Veterans Stadium, looming just beyond the highway to the south. An ugly ball park, outside and in: intersecting slabs of pre-fab concrete, balding artificial turf, bad food. The locals don’t seem to notice. The stadium suits them. They wouldn’t know beauty if it ran up and bit them on the ass. Here was beauty, circling a drab little track where only smeared chalk lines separate the lanes.

“I’m not sure I can afford Gianna,” I said. “You’re her friend, right? The one with the Grand Am.”

“I’m her lover,” Ronnie said cheerfully. “And you’re right, you can’t afford her.”

It was sad, the way she distanced herself. Our hearts were beating as one, our footfalls synchronized and so silent I could hear Armond 50 yards ahead, telling tall tales about life before he was gelded, describing nights he treated showgirls from the Trocadero to sausage sandwiches at Pat’s Steaks.

“You must be bisexual,” I said, with a sidelong glance at Ronnie. “You’re too attractive to be totally queer.”

She rolled her eyes, as I was expecting, and said, “According to you, I look manly. What’s that say about your sexuality?”

That got me thinking about the sexual orientation index, developed by an ex-colleague in Vermont for articles in several obscure journals. I called his questionaire the homo factor index, to deflate his pretensions to scientific method, and to annoy him, especially after he said my narcissism indicated latent homosexuality. Before his breakdown, he was working on an instrument that would take the guesswork out of gauging orientation. I still get a kick out of applying his concept, albeit with facetious intent. If my ‘mo factor is 3 on a scale of 10, then Ronnie’s must be 7. Unless she was putting me on.

“Who knows?” I said after 30 yards of silence. “Some effeminate guys are straight, some football players are as queer as Liberace. I have no desire to fuck men, if that’s what you mean. But I do like bisexual women.”

It was an invitation of sorts, but Ronnie wasn’t biting. She wiped sweat from her glistening brow with the back of her left hand, exactly as I do, and said softly, “Just leave Gianna alone. She has enough problems.”

I could have told her about problems - two ex-wives, two mortgages, three kids, a lawsuit that won’t go away, an untenured professor’s salary - but instead I said, “Are you her lover or her mother?”

It took balls for me, of all people, to ask that, given my insatiable need for female affection.

“Let’s say I’m her sister,” Ronnie said pleasantly. “Don’t mess with my sister, mister.”

And then my twin - my sister - veered toward the driveway and disappeared behind the parked cars. OK, I exaggerate. She’s not my twin, except maybe in the metaphysical sense, although she has yet to realize that. Maybe the quaint expression “better half” is more accurate. Or simply “other half.” She shaves under her arms, I hope. I draw the line at that. And at penises, of course. I’m confident Ronnie doesn’t have one of those.

I stopped next to the bleachers to pick up my water bottle, then started the half-mile walk that ends my workout. The Gang

of Four was directly behind me. Armond had changed the subject from prostate cancer to coronaries, which seemed to spark fewer objurgations from his cronies.

“I was dancing with my daughter at her wedding,” he declared. “My heart started racing till I thought it would bust. I went to sit down and collapsed face-first in a big bowl of onion dip. Soon as I got out of the hospital, I started exercising. It beats pushing up daisies.”

To each his own, but who needs half a man with a healthy heart? I’d rather help the flowers grow. Byron, at least, knew when to check out.

Armond was still holding court when I left for breakfast with Carla, my part-time girlfriend with the big breasts and the homemade bread and the bankrupt theatrical company. Not my twin, by any means, but a real wiz at reminding me that all the parts are still screwed on. She has pet names for our privates and a color photo of my smiling face on the dresser with the drawer full of toys and special jellies. A few hours with Carla before my afternoon classes will boost my sagging morale and bring my ‘mo factor back down to zero.

Only then can I think of colliding again with Ronnie. She’d like me to believe she’s happy playing big sister to bovine beauties like Gianna, but I know her quicksilver sadness and its secret cause: She hasn’t had a lover like me yet. Someday I’ll spell it out for her. I can already hear her laughter as she ducks behind the walls.

|

the world in concise terms

by sydney anderson

a mini dictionary of useless and vastly important words

by me

aardvark - a creature that sucks up things that aren’t cool and uses them for food. wow. the destruction of crap in order to survive. also one of the ugliest animals ever.

AIDS - a disease which no one understands. the doctors can’t find a cure, the infected don’t know why it happened to them, and the ignorant think that gays and lesbians have cooties.

anvil - a carton weight dropped on someone’s head for laughs. wish i could do that to people. it’s meant to hurt them, i guess, but the cartoon characters are always in perfect shape by the beginning of the next scene. ah, realism in television.

apple - something that’s supposed to keep the doctor away. fiber, i guess, as well as just eating something good for you instead of super-processed, refined, bleached, reconstituted shit. still don’t know how spraying the apple orchards with chemical pesticides, then covering the fruits with wax for shine is supposed to be good for you,but there are a lot of things i don’t understand, which you’ll soon understand.

condom - a zip-lock baggie for a penis. however, you can’t seal it with a yellow-and-blue-make-green zipper-gripper. *Fun gag: put a lubricated condom on a door knob.

cervix -

gelatin - the spare parts, including bones and connective tissue, of assorted animals, including horses, pigs and cows. this delectable, delicious delicacy can be found in such unobtrusive treats as jello and gummi bears.

heaven - a place for souls to go after they die (note: this is a myth). though there are many interpretations, some include streets of gold, or a separate heaven for your pets (though these same people are more than happy to eat other animals), or a place where you can see your dead grandmother again. my question: do you go to heaven in the condition you were in when you die, i.e., if your death entailed dismemberment, would your body be separated in heaven for eternity? do babies spend eternity as cooing, pooping vegetables?

money - something all artist claim to hate. (if they won the lottery, they’d swear they never said it.)

nirvana - (1) a good band. (2) a fantasy-state of perfection.

police - fat men with moustaches who wear tight blue uniforms and speak as if they are entirely uneducated. Note: they are dangerous; they also carry guns. Police serve two functions: to hand out traffic tickets, which make them inherently evil, and to arrive at the scene of the crime too late to offer any real assistance and to merely harass the victim so they feel victimized twice in one day.

poopy -

redneck - though seemingly everywhere and quite annoying, it is difficult to define a redneck. you can spot a redneck if (1) they live in a trailor; (2) they have a front lawn with: (a) appliances, (b) many junk cars; (3) they are missing teeth; (4) they are drinking coors beer, (5) they think wrestling is real. they congregate at (1) monster truck rallies, (2) wrestling matches (of course). note: their shotguns make them dangerous (but not their brains).

religion - a belief system created and/or perpetuated by a society to explain what happens when people die, because (1) they’re too afraid to become worm food, or (2) people need something to be afraid of in order to be good to others. note: it still usually doesn’t work.

|

|

another god-damned easter poem

by ray heinrich

most of you was naked

i

on the other hand

was getting close

to the end of the conveyer belt

dumping us off into the abyss

or

into all the chocolate we’d ever want

but

there was no way to find out

which

it was

it seems that way with us

all of us who vowed

to always sleep naked under the same sheet

now you can walk up on the proverbial street

and ask either of us this question

and get a reply like you’d expect

from nazis at nuremburg

or commies before HUAC

or some poor queer bastard

needing a break from a judge of 85 who knows

this pervert should be damned

i can’t help any of this

i tell myself i got to take a shower

and wash all this off for an hour or two

wash the sins like the girl called christ

(she was in drag)

that died

or didn’t

a few days from now

i have no idea what to make of all that

these people come to my door

and tell me one thing

and after 3am on TV

some other people tell me ten other things

but all of them

want me to send my money

where can i find christ

so i can give it directly to him?

will it burn my hands when i do this?

will i perish in fire for some vile perversion

that i forgot about?

or will i be forgiven?

i really need to be forgiven

like everyone i know needs to be forgiven

for watching the starving people on TV

for truely feeling compassion

for about 15 seconds

till the next commercial tells me

to buy corn chips

and I WILL

oh god i promise I WILL

buy them

and eat each one savoring it

as it changes to YOU my CHRIST

changes on this EASTER of remembrance

changes to the flesh of the flesh i am eating

and grows large in me

i sometimes think of the child i am to bear

of my mother telling me

i could never do this because i was a boy

but i never could believe her

and i refuse to this day

i will become large with my savior

i will give birth to some salvation

and the truth that has always escaped me

shall be evident to this child

which i will press from me

in pain and victory

like the rock

upon which all that follows will be built

|

Page 133

J. Speer

Life in Paria, Utah, was calm and uneventful until Raymond Manning arrived. He played guitar and sang original tunes at night. We burned boards off the sidewalk from the old movie set for our campfire.

His motive for playing music was to capture an audience. He had strong ideas he wanted to convey to people and he realized expressing himself through music was stronger than the written or spoken word.

He was greatly encouraged by his grandmother. She still had her driver’s license but had stopped driving. Raymond driver her to the store and waited in the car as she pushed her shopping cart up and down the aisles, matching coupons with products. He practiced his cord changes while he waited in the car.

She insisted that he serenade her after he unloaded her groceries. She did not want to hear his protest songs. She enjoyed songs like “The Old Rugged Cross” and “Rocky Top”. He tried to introduce her to recent music, especially the late Yardbirds lineup with two lead guitarists: Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. But she rejected that as a devil’s brew.

One day she felt very spunky and wanted to drive herself to the store. Raymond did not consider this a good idea. Before she stopped driving, she had knocked down two mail boxes and almost ran over a lady pushing a perambulator. He felt she was lucky to call it quits before having to file insurance claims or incur extensive medical bills. The idea of her behind the wheel again was frightening. But he knew if he negated her freed

om of choice she would be on the road again in half no time.

He encouraged her by changing the oil and filling the tank up with high octane gas. This startled her because she expected resistance. He even suggested she drive at night to avoid traffic.

Raymond secretly had her car set upon blocks. He rounded her up one dark night and offered to accompany her as she drove the car. She was reluctant but he hustled her out to the driveway and helped her into the driver’s seat. She was nervous and didn’t realize the car was propped up. She started the car and shifted it into drive. Raymond directed her.

“Step on it, granny. Stop here. Turn left. Turn right. Look out. You almost hit that kid on a bike.”

After ten minutes of “driving”, she wanted to park it. He directed her back home. He helped her out of the car and into her room. She was a bit shaky after the experience and never talked about driving again. Raymond continued to rib her with comments like: “Hey, granny, let’s make a cross country trip. We can take turns driving.”

|

visiting hour

by michael mcneilley

the rain paints a glow

around each arc light

high above the yard

like haloed harvest moons

and water drips and sparkles

on the chain links.

the moms are not

on average bad-looking -

one in tight knit pants

another with flowing red hair.

they leave one at a time.

they do not speak.

then a mom and a dad

come out together

gesturing against

the glaring dark

their mutual laughter

incongruous

but their faces harden

as they divide toward

separate cars.

and the door buzzes out

another mom who turns the corner

and I see the common feature -

a stiff set to the jaw

eyes somehow unfocused

and a walk too quick

not brisk but more as if

afraid they might begin

to run.

one or two attempt a proud

look of self confidence

but their eyes betray -

shadows surround them

from the many lights -

they walk in pools of shadows.

and you turn the corner

past the red sign that reads -

Warning! Juvenile Detention -

framed by lights and barbed wire

you are momentarily

unfamiliar.

your face in that same set

like some sort of stroke victim -

your eyes pools of sorrow

and I spill this sad cup

of coffee that was all

I thought to bring you.

you stand there in

the shadow of the car -

out of the lights nothing

in your hands and we wait

to look each other

in the eye

and watch instead

the rainy blacktop

and the one short shadow

you cast now -

the size of a

small boy.

and glancing back together

we must look away again -

look up to see

the moon has built

a fence

against the stars.

|

group dynamic

by michael mcneilley

he runs from his mother

but she is not he

r

she chases her father

but I am not him

I pull the gun

from my mouth

and point it

at you

|

silence means consent

by michael mcneilley

we take our argument elsewhere

and as the door shuts behind us

she sponges up the anger

brushes out its bristled fur

and feeds it chocolates and apologies

anticipating our return

|

C A R T I L A G E S

BY PAUL L. GLAZE

True Be Our Legs Of Two.

Cartilage’s Of The Knee Cap.

These Are Great, But Very Few

As Age Makes Our Knees Nap.

Truly It Is A Shame

When We Wear Them Out.

But Who Is To Blame

As We Race And Run About.

Injury Is The Common Cause,

We Play And Enjoy Our Game.

This Expansion Of Natures Laws,

Once again, Who Is To Blame?

We May Live Again Someday,

Who Knows How Life Does Track.

I Only Hope To Find Away

To Bring Some Extras Back !

|

THE CEILING FAN

By Paul L. Glaze

That fan up in the ceiling

Really reminds me of me.

It’s moving kind of fast,

But going nowhere, don’t you see.

Them blades are really spinning

Going round and around.

They ain’t going nowhere

But wearing them self’s down.

The fan up in the ceiling

Shows me life’s not really fair.

Cause me and that old fan,

Are just blowing out Hot Air !

|

Chimes Of Times

Paul L. Glaze

{ Losing A

Re-Election Bid }

A Politician Becomes A Musician

His Office Is The Instrument He Plays.

Its Music Is Soothing And Exotic.

They Revolve In Its Rapturous Phase.

When There Is A Voter Separation

Terrible Thoughts Their Mind Displays.

A Sense Of Instant Desperation

Of Whatsound Of Music Plays

In Their Post Political Days

They Will Secure Then Endure

A Rebirth And Back To Earth

As A Human In A Natural Daze

And Be Forced To Live As Normal

The Rest Of Their Natural Days.

At This Date,

They Now Have Met,

A Fate So Usually Cruel,

Called, Ballot Box Death

They Fall Into Hell

After They’ve Fell.

And Spend Their Time

Where Us Human’s Dwell!

|

C O L O R S

By Paul L. Glaze

(All Souls Are Colorless)

I Am Pleased I Was Born A Pure And Perfect White.

I Would Not Like To Have Worn The Color Of The Night.

Was There Something I Did To Select This Sacred Shade.

Perhaps I Hid From The Ethic Birth Parade.

I Do Not Know If White Was My Personal Selection.

But Wherever I Go, It Receives Fond Affection.

We Whites Have Ordained Ourselves To Be Superior.

Therefore All Others Must Be Inferior.

The Color Of Ones Skin Is How We Pick And Choose.

By Its Lightness We Win, By Its Darkness We Lose.

It Is Somewhat Nice When White Is Our Precious Skin.

Then We Pay Our Price When It Turns Dark Once Again.

We Would Discover If We Only Take The Time

The Color We Would Uncover Is Only A State Of Mind.

Be Careful With Colors And Not Wear Them With Vanity.

For These Same Colors May Be Used To Test Our Sanity.

It Is Important We Be Fair To All Colors We Chance To Meet.

Those Colors We May Wear. Our Next Trip Down Life’s Street.

There Is A Feeling If You Dislike A Certain Color Tract

It Will Have A Revealing

When Your Spirit Travels Back.

Many Colors Fate Has Arranged As We Live Thru Various Stages.

These Colors Are Changed As We Live Through Out The Ages !

|

COLORS

{ All Souls Are Colorless }

Paul L. Glaze {C}1995

I Am Pleased I Was Born

A Pure And Lily White.

I Wouldn’t Like To Have

Worn The Color Of The Night.

Was There Something I Did

To Select This Sacred Shade.

Perhaps I Ran And Hid

From The Ethic Birth Parade.

I Do Not Know If White

Was My Personal Selection.

But Wherever I’d Go,

It Receives A Fond Affection.

Whites Have Thus Ordained

Ourselves To Be Superior.

Therefore All Others

Must Be Inferior..

The Color Of Ones Skin

Is How We Pick And Choose.

By Its Lightness WeWin,

By Its Darkness We Lose.

It Is Very Nice When

White Is Our Precious Skin.

Then We Pay The Price When

It Turns Dark Once Again.

We Would Surely Discover

If We Only Take The Time

The Color We Would Uncover

Is Only A State Of Mind!

Be Careful With Your Colors

Don’t Wear Them With Vanity.

For These Same Colors May

Be Used To Test Our Sanity.

It Is Important We Be Fair

To Colors We Chance To Meet.

Those Colors We May Wear,

Our Next Trip On Life’s Street

There Is A Certain Feeling

If You Dislike A Color Tract

It Will Have A Close Revealing

When Your Spirit Travels Back.

Many Colors Fate Has Arranged

As We Live Thru Many Stages.

These Colors Are Changed

As We Live Through Out

The Ages !

after 25 years we’re here

by michael estabrook

rehashing high school,

weightlifting and gymnastics, his

dogs, my hamsters, his sisters,

my brothers. Over the years

so much life has flowed

through, over and around us like

a grand unstoppable impatient

river. And we’re different, we’ve

grown, changed and learned, but

then again we haven’t.

|

Buildings

by michael estabrook

buildings always buildings and I’m lost in them

. . . in a skyscraper with fast moving elevators that don’t stop that go up

to the roof and beyond the roof and I’m alone in there in this small

all-glass skyscraper elevator and I can’t get out . . .

. . . in this Victorian mansion with hidden rooms and musty-smelling

crawlspaces and pantries I’m in the attic climbing in and out windows being

chased by something dark and heavy and hairy through the attic out onto the

roof back into the attic again and again . . .

. . . in a sprawling dusty farmhouse long endless crooked hallways rusty

smell of damp grain . . .

. . . in a giant college classroom building wide stairways alcoves echoing

alcoves windows tiny windows that peer out over an empty quad and I can’t

find my classroom it’s exam time and I’m late and I haven’t been to this

classroom in months I don’t know why I think I’ve simply forgotten this class

and I’m searching up and down the wide stairways alone in the alcoves peering

out the empty windows I can’t find my classroom . . .

in my dreams I’m always in buildings lost in buildings in my dreams I’m lost

in buildings

|

dear Rachel,

by michael estabrook

But actually there isn’t a whole

lot to say about me. I suppose if I had

it to do all over again I’d become

a Marine Biologist, specialize in ecology

and in environmental issues,

maybe be on the Company Inspection

Team, shut down some of these big

damn impersonal corporations that seem truly

to enjoy polluting the hell out of the planet.

I’d try to explain to people that

if they ruin the Earth, well there simply

isn’t anyplace else to live.

But in the meantime, I’ll just

keep on working, trying

to make some money

seeing as I have 3 children to put

through college; will have 2 in

this coming year, thought I had it knocked

too, had identified where the money

would be coming from,

my daughter having chosen

a college that was only $15,000 a year

and because she’s a serious student

she got $5,000 in scholarship money,

but then at the

11th hour she decides to go

to a better school, Bentley College,

one of the best in

the country for business which is

what she wants to major in, and bang

just like that we go from $5,000 per

semester to $11,000 per semester so

it’s is back to the

drawing board in search of funds,

maybe I’ll get myself that part-time job

I always wanted, the one

in Sears or Taco Bell.

|

carol brown

E-mail Carol 2080@aol.com

Who’s memo is it anyway? *

you ask me to write a pleasing, mild-mannered direct order

expecting it to sound like sugar coated desert

wanting acceptance from those over whom you lord

with no understanding at all of their feelings

perhaps with more, far more perception of their nature

than i could ever be capable of..

who made you king?

i wonder where is it written that your word is law?

oh to be so correct, so perfect all-knowing

what’s best for everyone man

it must be a tremendous burden to bear

the fate of the world in your mind

in your mind

so i write

(*This was written by the Asst Dir. of the campus security dept. A long time friend, former NYPD Lieutenant, who has been the inspiration and driving force behind my starting to write verse. The above was written as a result of his run-in with a (simon legree) boss you know the type! Smile and stick the knife in!!) My friend’s nick name is “Warlock” he calls me”Da’ Witch” (Bronx accent for “The Witch” -smile

* Feline*(also by Warlock)

If cats had lips

would they play

the piccollo?

Dreams-Warlock’s Haiku (I wrote these with the Warlock looking over my shoulder and a bottle of Pinot Grigio(Peanut Gregory-Bronx dialect)

***

Autumn’s shiver

Winter’s approaching kiss

Summer’s hot dreams.

Flowing waters

echo moaning

a cat smiles.

Heartbeats in the dark

short, deep breaths

moist internal quivering.

Campus nights

waking dreams

a quaking moon.

leaves rustle

soft indecent breeze

erect anticipation.

Cat’s tongue

licking hot skin

Disires’heat

|

Kid, Japan

chuck taylor

Sakuma park it was by the

red arched bridge over

the Cedar shrounded pond-

stone steps maybe a thousand

years old going up a hill

going nowhere, and your tiny

feet climbing up and down,

up and down, holding my hand

with such sure purpose and I,

tinged with melancholy,

conscious kneeling saying

hold this

hold this

it will not last...

|

Cherished Possession

By Peter Scott

From a deep slumber

I hear the tone of a voice

Residing inside an irate contraption

A little box

That stores your soul

In moments you are too far to touch

And when I need

During those trials and pain

The little box begins to wail

Signaling my sudden salvation

From there

All I must do is open myself to your soul

Lift the receiver

Letting the reassuring touch of your voice

Interplay with the sounds in my head

Making sense of jumbled distortion

Allowing me to make amends with the world

Take a vacation for awhile

Each day

Sometimes even make love to you

In the mind

The box that holds this piece of you

Is practically a religion to me

A connection to the soul

I dearly regret

Parting from the mad box

Like a magic lamp

Where all I must do

Is caress you in the mind

So tenderly

And you will be there

Granting every wish

With a harried smile

Only worrying a bit

As to not spoil me with abandon

I guess the ornery contraption

Works only as a figurehead

Though

For at night

In the woods alone

Whispers cease not a bit