|

Dusty Dog Reviews The whole project is hip, anti-academic, the poetry of reluctant grown-ups, picking noses in church. An enjoyable romp! Though also serious. |

|

Nick DiSpoldo, Small Press Review (on Children, Churches and Daddies, April 1997) Children, Churches and Daddies is eclectic, alive and is as contemporary as tomorrow’s news. |

|

Kenneth DiMaggio (on cc&d, April 2011) CC&D continues to have an edge with intelligence. It seems like a lot of poetry and small press publications are getting more conservative or just playing it too academically safe. Once in awhile I come across a self-advertized journal on the edge, but the problem is that some of the work just tries to shock you for the hell of it, and only ends up embarrassing you the reader. CC&D has a nice balance; [the] publication takes risks, but can thankfully take them without the juvenile attempt to shock. |

|

from Mike Brennan 12/07/11 I think you are one of the leaders in the indie presses right now and congrats on your dark greatness. |

Volume 241, February 2013

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

Cover art by John Yotko

see what’s in this issue...

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

|

Order this issue from our printer as a paperback book (5.5" x 8.5") perfect-bound w/ b&w pages |

poetry

the passionate stuff

UZEYIR CAYCI DPAT8K, art by Üzeyir Lokman ÇAYCI

I Ran Outside to HearBradley Bates

The remaining acre uncut.

and I wanted night to fall

one remains unsure of

skillful he becomes rightfully

|

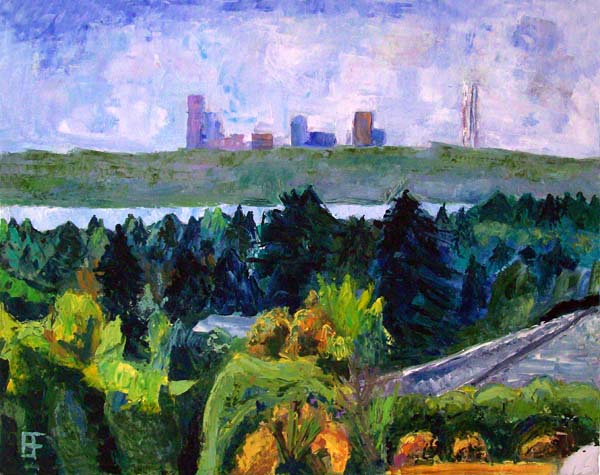

Bellevue hilltop road view of Seattle, painting by Brian Forrest

FanaticsWilliam Robison

Flames lick at the stake

Flames climb up the cross

Flames consume the street

Flames in the towers

Flames of pundit’s torch

|

William Robison BioWilliam Robison teaches history at Southeastern Louisiana University and has published considerable nonfiction on early modern England, his most recent work being The Tudors in Film and Television (McFarland, 2012), co-authored with Sue Parrill. For more info, see http://www.tudorsonfilm.com. He is also a musician and a maker of short films, both which the curious can check out at http://www.myspace.com/562067730. Poetry is a newer form of expression for Robison, but recently hwe has had poems accepted by Amethyst Arsenic, amphibi.us, Anemone Sidecar, Apollo’s Lyre, Asinine Poetry, Carcinogenic Poetry, decomP magazinE, Forge, Mayday Magazine, On Spec, and Paddlefish.

|

Wiggle In The GrassEric Burbridge

I rested my sweating feet in the cool grass

My rest ceased when the little black viper wrapped around my foot

I shook it, but it clung

It didn’t move, but it arched up and seemed to look me in the eye I was so embarrassed.

|

Mister and Mrs Quacktail, art by Nick Brazinsky

Firearm PhilosophyEsteban Colon

shotguns don’t get high.

shotguns

shotguns live for the kill

shotguns

|

| Janet Kuypers reads the Esteban Colon poem Firearm Philosophy from the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Esteban Colon poem in the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine live 2/13/13 at the Café Gallery poetry open mic she hosts in Chicago (from the Canon camera) |

Who’s the dummy?CK Baker

Read me that passage once again

Samuel was his name

He was a descendant of the Eastern block

A big belch

Hey wait

|

Truth IsDavid Michael Schmidt

Truth is like a pool of water

to disrupt that pool of water with a pebble

|

Modern Olympian Ode #2 (2012):

Michael Ceraolo |

| Janet Kuypers reads the Michael Ceraolo poem Modern Olympian Ode #2 (2012): The Apparently Once and Future Obscenity from the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Michael Ceraolo poem in the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine poem 2/13/13 at the Café Gallery poetry open mic she hosts in Chicago (from the Canon camera) |

Untitled (hands)Simon Perchik

You come here to bathe -the dirt

-you almost drown, crushed

and all these stones adrift

with the drop by drop

for flowers and your hands

|

| Janet Kuypers reads the Simon Perchik poem Untitled (hands) from the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Simon Perchik poem in the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine poem 2/13/13 at the Café Gallery poetry open mic she hosts in Chicago (from the Canon camera) |

Sea Side, art by the HA!man of South Africa

Open CampusRyan Peeters

I sat in English class, lollygagging

Pop! screams, then the sound of 40 or 50 people

The boy’s name was Buddy Guitron.

Someone else knew where Buddy would be.

The shooter ran.

Buddy’s hands were twitching from his side

I wanted to watch. I stood for a few seconds, walked near,

I wanted to stay and kneel. That required conversations;

|

God is the concept

CEE |

Energy

CEE |

Black Mask Hanging High

Mel Waldman |

BIOMel Waldman, Ph. D.Dr. Mel Waldman is a licensed New York State psychologist and a candidate in Psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies (CMPS). He is also a poet, writer, artist, and singer/songwriter. After 9/11, he wrote 4 songs, including “Our Song,” which addresses the tragedy. His stories have appeared in numerous literary reviews and commercial magazines including HAPPY, SWEET ANNIE PRESS, CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES and DOWN IN THE DIRT (SCARS PUBLICATIONS), NEW THOUGHT JOURNAL, THE BROOKLYN LITERARY REVIEW, HARDBOILED, HARDBOILED DETECTIVE, DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE, ESPIONAGE, and THE SAINT. He is a past winner of the literary GRADIVA AWARD in Psychoanalysis and was nominated for a PUSHCART PRIZE in literature. Periodically, he has given poetry and prose readings and has appeared on national T.V. and cable T.V. He is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Private Eye Writers of America, American Mensa, Ltd., and the American Psychological Association. He is currently working on a mystery novel inspired by Freud’s case studies. Who Killed the Heartbreak Kid?, a mystery novel, was published by iUniverse in February 2006. It can be purchased at www.iuniverse.com/bookstore/, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. Recently, some of his poems have appeared online in THE JERUSALEM POST. Dark Soul of the Millennium, a collection of plays and poetry, was published by World Audience, Inc. in January 2007. It can be purchased at www.worldaudience.org, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. A 7-volume short story collection was published by World Audience, Inc. in June 2007 and can also be purchased online at the above-mentioned sites. |

Freshman High FootballDana Stamps, II

Once again, a fat kid, slow, exhausted, near collapse

ordered the second biggest kid on the team

Without delay, the crunch of shoulder pads, the grunt,

“Get up, Patterson! Get up now, and get in line!

But the fat kid did not get up, and I was worried but he showed up for practice the next day.

Two months earlier, the first day of the semester,

|

It Fled Away, art by Edward Michael O’Durr Supranowicz

The Free Market (La Serrata*)I.B. Rad

Who ever coined that phrase, *Why La Serrata? Google “La Serrata and Venice” and see!

|

| Janet Kuypers reads the I.B. Rad poem The Free Market (La Serrata) from the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this I.B. Rad poem in the 2/13 issue (v241) of cc&d magazine poem 2/13/13 at the Café Gallery poetry open mic she hosts in Chicago (from the Canon camera) |

AndersonJanet Kuypers6/4/12

I started having pets

I’d go to the pet superstore

There was no air filter,

after ex-boyfriends,

But then I decided

So I got this little salamander.

So Anderson sat in a goldfish bowl,

And I felt like I accomplished something

That summer I traveled around

once every few days

smell my flesh burn, my sister

but Anderson escaped.

And two months later,

we were looking for. That’s when

|

Watch the YouTube video of Kuypers reading this poem at the open mike 6/20/12 at the Café Gallery in Chicago (from the Sony) |

Watch the YouTube video of Kuypers reading this poem at the open mike 6/20/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon) |

Watch the YouTube video of Kuypers’ open mike 6/20/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery in Chicago, which includes this poem |

Etiquette for Tattooing

Janet Kuypers |

Protect Ourselves

Janet Kuypers |

Ever Expanding SpacesJanet Kuypers6/4/12

I can’t sleep.

|

See YouTube video of Kuypers reading this poem at the open mike 7/4/12 at the Café Gallery in Chicago (from the Canon) |

See YouTube video of Kuypers reading this poem at the open mike 7/4/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery in Chicago (Sony) |

See YouTube video of Kuypers’ open mike 7/4/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery in Chicago, plus her reading poems, including this one (w/ live piano from Gary) |

Overweight ReasonsJanet Kuypers6/2/12

An obscenely overweight woman

|

Janet Kuypers Bio

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006. |

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

You believe the Heritage Foundation, there is no poverty.Fritz Hamilton

You believe the Heritage Foundation, there is no poverty. The people I saw huddled in a doorway, the mother & three young kids, weren’t there, the children cold & crying, the glassy eyed mother with no teeth, having them knocked out last night by her most recent lover, they are illusions, & the Southern California weather is not below freezing. All the other homeless I pass in the frigid rain on my three block trek home can’t really be there. The stats from the Heritage Foundation will show they don’t exist.

! (& if you run real fast, you can catch John’s head before it rolls into the manhole ... !)

|

The child is crushed beneath the cabFritz Hamilton

The child is crushed beneath the cab. The mother screams & begs the gathering crowd to do something. The cabby is hysterical, & a fat woman tries to hold him. This is Pasadena, outside my building. I phone 911. They already know. A cop pulls up. The fire engine approaches with siren howling.

|

Back DoorChris Allen

Matt had been obsessed with Susan for over seven years. Now, at the age of 20, he never believed that he would be walking up Susan’s front walk, up the thirty-six steps that went up a hill that connected to her front porch, and to see Susan herself.

Dear Prudence open up your eyes

Look around round round

Dear Prudence let me see you smile

|

Chris Allen bio (2012)Chris Allen is 21 years old and started writing short stories at the age of eighteen. None of his short stories have been published yet, but has had some interesting work in printed journalism and even his own radio show where he guest starred, “friend of aliens,” Riley Martin from the Howard Stern Show.

|

Jackson’s GhostJim Meirose

Crowley sat at his desk in the warehouse each day assiduously working—but working for what? To get yet another stack of orders dropped into his inbox? It was as bad as being out on the floor picking orders or packing orders. What am I doing this for? The orders kept coming one after the other. Each order required his undivided attention. He carefully added up the rows of figures and checked out the codes and descriptions on the orders and then he put the order into the out box. There was always a full in box. There were orders bursting at the seams to be worked. He had no one to talk to, no one to bitch to. Just his little desk in the corner by the door to the computer room where they printed the orders. And then Jackson would come up and take them out of the out box and take them up to the picking line. He wondered why, if these were produced by computer, there was so much manual adding of columns and looking up codes for each total in the big reference book he had by him—why couldn’t that all be done by computer? He asked Jackson one time.

|

Decisions of Life 15, Linoleum Block Print art by Aaron Wilder

Eddie Maria and the Knights of the 90William de Rham

Eddie Mara hit the Portland city limit and raced the motorbike he dreaded up Congress Street. He’d sworn to Stacy he wouldn’t be late for the Starbuck’s meeting with her folks to plan their wedding.

All around him, sturdy single-family homes sat on small, well-tended lawns under oaks and maples just beginning to green. So unlike the hard Dorchester streets he’d grown up on in Boston. Normally, Portland’s streets acted on him like a tonic, relaxing him, inviting him to feel safe and secure. But not today.

He woke up days later to sunlight streaming through a window and his Ma and Stacy looking down at him. He struggled to sit up, but his left side felt anchored. A heavy cast ran from his shoulder to his hand.

|

William de Rham biography |

Canary HeavenBob Johnston

New York Times, December 22, 1985 This dispatch, dated November 21, 1985, did not reach our editorial offices until yesterday. The reason for the one-month delay is unknown. We are printing the lengthy dispatch in its entirety, in view of the importance of the research it describes.

Baku seems an unlikely venue for advanced research. Yet this is where Doctor Boris Ivanovich Kazansky has labored for more than twenty years at the frontiers of cellular biology and genetics. In a huge concrete-walled building, hemmed in by two oil refineries just north of the city limits, Dr. Kazansky has created a large population of what he calls “super-canaries.”

After a delay of more than three months, I finally secured the clearances required for entry into the massive building that houses a major research project on the cutting edge of biological sciences—a project heretofore cloaked in secrecy. According to the Baku Commissar of Security, I am the first outsider to enter this fortress of research since its dedication in 1963. While this great honor weighs heavily on my shoulders, I must admit, without any false modesty, that I am eminently qualified by education and experience to bring the story of Dr. Kazansky and his canaries to a waiting world.

At the beginning of our tour, Dr. Kazansky summarized the history of this unique facility and an astounding research program spanning more than a century. His grandfather first became interested in canaries as an object for genetic research in 1850, when he traveled to the Amazon rainforest and observed the huge variety of colorful songbirds. Among eighteen hitherto unknown species and variants that he discovered was a bird resembling the domestic canary but much larger, with yellow plumage that dazzled the eye. Its song, somewhat similar to that of the domestic canary, was far louder and had many more variations. Dr. Kazansky’s grandfather reported that some of these birds sang so beautifully he thought he recognized familiar tunes. He brought back twelve of these canaries, eventually named Serenus canarius Kazansky. These twelve, along with the hundreds of birds subsequently brought back to Baku by the two elder Kazanskys, formed the basis for a study of natural and induced mutations covering sixty generations of canaries and three generations of the Kazansky family. The canaries proved to be ideal subjects for genetic research, as they bred relentlessly, each female producing at least six clutches of eggs annually.

Dr. Kazansky related this fascinating history as we walked through the length and breadth of the first floor, for the most part filled with very ordinary-looking offices. We then descended to the lowest of six underground levels, where I saw massive air-conditioning machinery, a water treatment plant, a hydroponic garden, refrigerated food warehouses, huge turbogenerators, and an electric power distribution station. Illumination came from a luminous ceiling, which was at least twelve meters above the spotless white floor. We encountered only four technicians, dressed in white coveralls bearing the Institute logo. Dr. Kazansky explained that all the machines and facilities were under full automatic control. He pointed to a door in the center of one wall—somewhat similar to an automatic garage door but much larger, at least eight meters in width and height. “Behind this door is a tunnel that leads to our nuclear power plant, eighty feet below the surface. Another tunnel, on the opposite side of the building, permits the entry of trucks bringing in food, equipment, and supplies. But in the near future we shall be able to grow or synthesize all our food; and eventually we shall become completely self-sufficient, capable of surviving any natural or man-made disaster with the possible exception of an all-out nuclear war.”

Our tour now took us to the aboveground levels. Dr. Kazansky took my arm and led me to an unmarked elevator. “Now, my dear Kolya,” he told me, “you will witness the fruits of our labor.” As we emerged from the elevator onto the fourth floor, my brain could barely encompass the enormity of the room that we entered. As far as the eye could see, it was occupied entirely by row after row of huge, shiny, black cubes, possibly four meters on a side. Dr. Kazansky explained: “These are our glass cages—or apartments, as we prefer to call them. This room, occupying the entire fourth floor, is just one of three such apartment complexes, now housing more than ninety thousand canaries. The glass walls that you see are currently in the opaque mode. Here, let me demonstrate.”

Dr. Kazansky ushered me to the top floor, where, in contrast to the other floors, a wing is walled off from the general population by a cement block partition and a heavy, barred security door. He pressed his thumb on an identification panel, and the door swung open. We entered, and the door closed behind us with a resounding clang. My first impression was that of a spacious gallery in a museum, each of the walls displaying several paintings that appeared to be originals; I recognized an El Greco and a Rubens. The room is spacious and uncluttered. In contrast to the “government green” of the other three residential floors, the walls here are painted a soft white, acquiring just a hint of rose from the overhead lighting.

Dr. Kazansky switched the next cage into the transparent mode, and I saw that its sole occupants were four coal-black birds, their sizes ranging from super-raven to small-robin, all wearing red-and-white striped vests. On a single perch in the exact center of the cage, the four canaries sat side by side in order of increasing size from left to right. “The particular genius of this group,” Dr. Kazansky explained, “manifests itself in their mastery of the entire repertoire of music written or transcribed for male vocal quartets—from Negro spirituals to the classics. They are now rehearsing barbershop quartets, in anticipation of a forthcoming concert.”

New York Times, January 5, 1987 This dispatch, under the byline of Nikolai Ilyich Myshkin, is the first report this newspaper has received from Baku since the Soviet Union imposed a blackout more than a year ago. Myshkin, an Izvestiya staff reporter, continuing his story on the Institute for Advanced Genetics Research, describes his efforts to regain access to the top-secret facility known informally as Canary Heaven. His story poses more questions than it provides answers. Nevertheless, we are printing this lengthy dispatch in its entirety, in view of the importance of the research conducted in this facility and the apparent threat to the future of the human race.

More than two years have passed since I reported on my tour of the facility known as Canary Heaven. Guided by the Director himself, Doctor Boris Ivanovich Kazansky, I was privileged to witness the astounding results of a unique program of genetic research. Starting more than a century ago with one South American canary species, the scientists at Canary Heaven, through selective breeding, have produced birds of all shapes, sizes, and colors.

New York Times, June 1, 1997 During the past decade, which has witnessed the breakup of the Soviet Union, we heard no news regarding the fate of the Institute for Advanced Genetics Research. Now, the following brief dispatch from Izvestiya correspondent Nikolai Ilyich Myshkin tells us that he is still on the job. His devotion is an inspiration to us all, and we are confident that he will bring to us the final chapter in the history of this unique institution.

More than ten years have passed since the Institute for Advanced Genetic Research closed its doors to the outside world. I shall continue my vigil from my headquarters in a small apartment, just two kilometers from what was once the front entrance of Fortress Canary Heaven.

|

Bob Johnston BioBob Johnston is a retire petroleum engineer and translator, a nonagenarian, and an ex-drunk. He lives in the original Las Vegas, New Mexico, with a wife and three cats. He is occupied mainly in an effort to complete his memoirs and The Great American Novel ahead of the Ultimate Deadline.

|

Gaping Maw, art by Rex Bromfield

Poet Par ExcellenceJoel NetskyAfter the established poets, there were open mike readings, where anyone could get up and recite. This one chap, a bit bedraggled-looking, his hands without material, approached the microphone. Into it he spoke. “I am the poet par excellence of the Neo-post-post-modern Age. My poem is untitled.

I think; Thank you.” He stepped down.

I thought, “I think; therefore, I thunk?”

I eat; Thank you.” He stepped down. Whether the ripple of chuckles like a slender brook through a landscape of imposing natural artifacts caused me to sound too serious or too sublime, the audience still dangling their feet in his pleasant current, after three poems I vacated the stage and returned to my seat. In the refreshment period after the recital I saw this cute chick talking with the poet par excellence; they both were smiling and at times even laughed. I popped cookies like a kid, and sipped at the wine.

|

Neon Glow Flowers, art by Cheryl Townsend

Debra Purdy Kong, writer, British Columbia, Canada I like the magazine a lot. I like the spacious lay-out and the different coloured pages and the variety of writer’s styles. Too many literary magazines read as if everyone graduated from the same course. We need to collect more voices like these and send them everywhere.

Children, Churches and Daddies. It speaks for itself. Write to Scars Publications to submit poetry, prose and artwork to Children, Churches and Daddies literary magazine, or to inquire about having your own chapbook, and maybe a few reviews like these.

what is veganism? A vegan (VEE-gun) is someone who does not consume any animal products. While vegetarians avoid flesh foods, vegans don’t consume dairy or egg products, as well as animal products in clothing and other sources. why veganism? This cruelty-free lifestyle provides many benefits, to animals, the environment and to ourselves. The meat and dairy industry abuses billions of animals. Animal agriculture takes an enormous toll on the land. Consumtion of animal products has been linked to heart disease, colon and breast cancer, osteoporosis, diabetes and a host of other conditions. so what is vegan action?

We can succeed in shifting agriculture away from factory farming, saving millions, or even billions of chickens, cows, pigs, sheep turkeys and other animals from cruelty. A vegan, cruelty-free lifestyle may be the most important step a person can take towards creatin a more just and compassionate society. Contact us for membership information, t-shirt sales or donations.

vegan action

Children, Churches and Daddies no longer distributes free contributor’s copies of issues. In order to receive issues of Children, Churches and Daddies, contact Janet Kuypers at the cc&d e-mail addres. Free electronic subscriptions are available via email. All you need to do is email ccandd@scars.tv... and ask to be added to the free cc+d electronic subscription mailing list. And you can still see issues every month at the Children, Churches and Daddies website, located at http://scars.tv

MIT Vegetarian Support Group (VSG)

functions: We also have a discussion group for all issues related to vegetarianism, which currently has about 150 members, many of whom are outside the Boston area. The group is focusing more toward outreach and evolving from what it has been in years past. We welcome new members, as well as the opportunity to inform people about the benefits of vegetarianism, to our health, the environment, animal welfare, and a variety of other issues.

Dusty Dog Reviews: These poems document a very complicated internal response to the feminine side of social existence. And as the book proceeds the poems become increasingly psychologically complex and, ultimately, fascinating and genuinely rewarding.

Dusty Dog Reviews: She opens with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, CA Indeed, there’s a healthy balance here between wit and dark vision, romance and reality, just as there’s a good balance between words and graphics. The work shows brave self-exploration, and serves as a reminder of mortality and the fragile beauty of friendship.

Mark Blickley, writer You Have to be Published to be Appreciated. Do you want to be heard? Contact Children, Churches and Daddies about book or chapbook publishing. These reviews can be yours. Scars Publications, attention J. Kuypers. We’re only an e-mail away. Write to us.

The Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology The Solar Energy Research & Education Foundation (SEREF), a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C., established on Earth Day 1993 the Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology (CREST) as its central project. CREST’s three principal projects are to provide: * on-site training and education workshops on the sustainable development interconnections of energy, economics and environment; * on-line distance learning/training resources on CREST’s SOLSTICE computer, available from 144 countries through email and the Internet; * on-disc training and educational resources through the use of interactive multimedia applications on CD-ROM computer discs - showcasing current achievements and future opportunities in sustainable energy development. The CREST staff also does “on the road” presentations, demonstrations, and workshops showcasing its activities and available resources. For More Information Please Contact: Deborah Anderson dja@crest.org or (202) 289-0061

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA want a review like this? contact scars about getting your own book published.

The magazine Children Churches and Daddies is Copyright © 1993 through 2013 Scars Publications and Design. The rights of the individual pieces remain with the authors. No material may be reprinted without express permission from the author.

Okay, nilla wafer. Listen up and listen good. How to save your life. Submit, or I’ll have to kill you.

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA: “Hope Chest in the Attic” captures the complexity of human nature and reveals startling yet profound discernments about the travesties that surge through the course of life. This collection of poetry, prose and artwork reflects sensitivity toward feminist issues concerning abuse, sexism and equality. It also probes the emotional torrent that people may experience as a reaction to the delicate topics of death, love and family. “Chain Smoking” depicts the emotional distress that afflicted a friend while he struggled to clarify his sexual ambiguity. Not only does this thought-provoking profile address the plight that homosexuals face in a homophobic society, it also characterizes the essence of friendship. “The room of the rape” is a passionate representation of the suffering rape victims experience. Vivid descriptions, rich symbolism, and candid expressions paint a shocking portrait of victory over the gripping fear that consumes the soul after a painful exploitation.

Dusty Dog Reviews (on Without You): She open with a poem of her own devising, which has that wintry atmosphere demonstrated in the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The atmosphere of wintry white and cold, gloriously murderous cold, stark raging cold, numbing and brutalizing cold, appears almost as a character who announces to his audience, “Wisdom occurs only after a laboriously magnificent disappointment.” Alas, that our Dusty Dog for mat cannot do justice to Ms. Kuypers’ very personal layering of her poem across the page.

|