When the Walls are Paper Thin

cc&d magazine

v259, Nov./Dec. 2015

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

poetry

the passionate stuff

|

We are all Turkeys!

MCD

11/29/2014

It was the night before Thanksgiving

and all through the mall,

not a shopper was stirring, just

a few under paid clerks, some

rent a cops with machine guns

in hand, and the corporate

bosses counting their swag

The shelves were spilling over

with every deal to be made,

TVs and consols, blue jeans

to toys, coffee machines, mix masters

and more, oh boy, just about everything

on sale for Black Friday’s Thursday

early shopper deals

With hours from opening the

hordes at the doors building

anticipation to tackle the floor

of thirty to fifty percent off their list

and a few seventy percent surprises

they never much even knew exist

So with a push and a shove

the masses stormed into the stores

grabbing the items like professional

thieves, making the racks empty,

unlike carrion of homeless asleep on

the streets,

No one notice not a child in sight

fighting broke out and two were shot

the images of Ferguson shown on

every tv screen, is there a right-way

or wrong-way of fulfilling our needs

the philosophers pondered both scenes

of Amerika’s steal

And soon the malls emptied all

was spent, not a nickel was left

to give to the poor, the homeless

the hungry have nothing but ills

while big corporations make well

of the swill

Another great capitalist scam

could be heard in the distance

as sirens wailed, taking poor

and non spenders, off to their

over spent jails

|

Woody Guthrie Plays the Nibelungenlied

CEE

I wonder at Dalton Trumbo

At Joe Bonham as imprisoned

Self

About the dying being not proud

Slipping away to Styx, still jingoist, re:

Red whites and their blues;

Recall Sesame Street

(The Electric Company?)

Old animate joke of

“We’re out of sweet rolls”

Whether or not human persons lie dying

From jackboot kicks

Of fascist guns recoiling

Dying having all the good songs, but

Dying, burning in snow or mountain pass

Stuffed doubled-candied sweet taters, as

Fucked as Thanksgiving turkeys,

Has what to do with Any ideology

Or glorious, spattered epiphanies

Out of whatever inclusive mouths

Of whatever babes

John Reed’s brethren, are eggshells, too

Your blood doesn’t taste sweet

Because your mind is open

|

Drones:

The sound r/c planes made in the 60’s Reality

CEE

The thingiebobbers work, all right

But make such a fucking racket

The “noise pollution” volk are out in force

Some people wind up hearing impaired

So, no deliveries before 11:00 A.M.

But, not everyone works the same hours

As you know, so,

As our world, as you know

Wasn’t set up for 3rdM/font> shift people

They all have to register

Like sex offenders

|

Poseidon Dies Like A Fool

In The Modern World

Doug Draime

A psychic whore left him stoned

in a dilapidated motel room

on the edge of a chasm

on the gray brink of a vast abyss

There remained 4 short lines of cocaine

on the night stand

like hammers for rusty, crooked nails

awaiting inevitable dense black clouds

The worms of earth would not

take his body and the sea threw it up

on shore like the trash of humanity

And the air ate it away gradually,

much akin to the putrid gas of betrayal eating

away the pure innocence of tenderness

|

untitled (muse)

G. A. Scheinoha

O you

grey mountain muse,

lamp as

fingers in mist,

pour through passes,

rise to graze

the high meadows.

|

Juvenile Ballet

Richard King Perkins II

I liked being flesh. I liked its impermanence

and because we were barely loved,

we had found each other—

open to touch and pleasant to opposing eyes.

Moonlight seemed always near and I enjoyed

how we could unmake a bed together,

elevated by another’s ending—

the measured awkwardness of juvenile ballet.

|

Pearl Skies Lying

Richard King Perkins II

Above the irregular valleys of Pennsylvania

swinging out of this morning’s mist,

the deepest yellow sun

can’t remember its ancient colors

before planets and all the rest

started following it around like needy pets

begging the elements of life.

Character actor in a cosmic picture—

the sun can’t recall its earliest bit parts

in white and blue,

portraying anger, sadness, resignation;

waiting for its breakthrough role—

to illume what I perceive at this moment;

your sensual currents

and the pearl skies lying below.

|

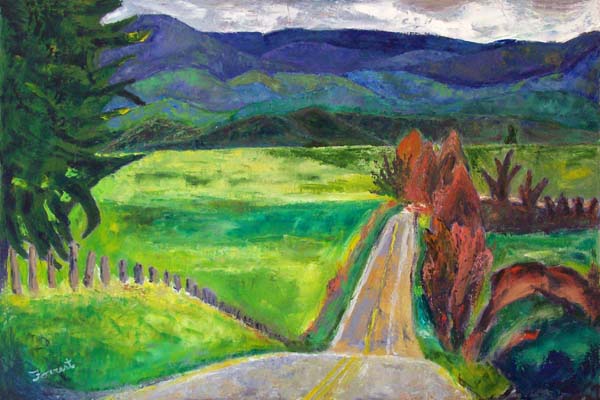

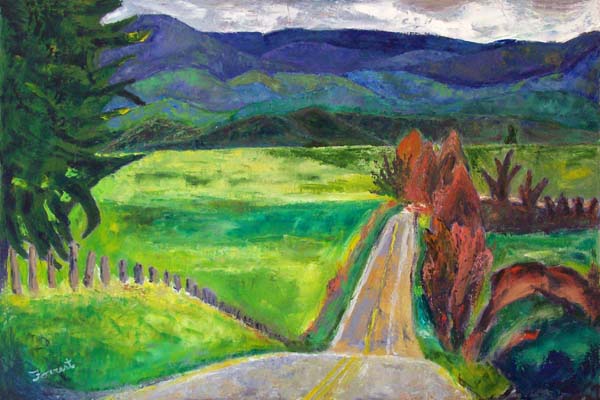

Brian Forrest Bio:

Born in Canada and bred in the U.S., Brian Forrest works in many mediums: oil painting, computer graphics, theatre, digital music, film, and video. Brian studied acting at Columbia Pictures in Los Angeles, digital media in art and design at Bellevue College (receiving degrees in Web Multimedia Authoring and Digital Video Production.) He works in the Seattle, WA area in design/media/fine art. Influenced by past and current colorist painters, Brian’s raw and expressive works hover between realism and abstraction.

http://brianforrest-art.blogspot.com/

|

Mobservation #7

Michael Ceraolo

More and more people used the new way

of becoming experts:

by

standing up and saying they were experts

And

as their ‘expertise’ often went unchallenged,

they adopted an unspoken slogan:

who says declining standards are a bad thing?

|

the scream of the butterfly

Patrick Fealey

it was late afternoon & this rock across the yard was the last ground in the sun. i walked to the rock & saw a yellow butterfly resting on it, the color of the inside of a lemon. it took to the air when it saw me. i sat down on the rock in the sun to think & drink. the yellow butterfly was back before my ass was warm. it landed on my head. it wasn’t screaming, but i guessed it had something on its mind. we sat there, the butterfly on me, me on the rock – in the same sun in the same spot on planet earth. then it flew into the maples. i got to feeling guilty. i didn’t come to the sunny rock to feel bad about stealing real estate so i stood up & walked away. i stopped & turned: the rock was in the sun & i waited . . out of the maples danced the butterfly, small yellow and fragile. it landed gently on the rock.

|

Pink Photosketch0001, art by David Russell

innocence & experience

Patrick Fealey

he fucked his daughter

he fucked my girlfriend

there was a time when i didn’t know how evil

the world was and there is a piece

of that kid in this poem

and a couple of dead kids, in this poem

elizabeth and i shared a table in 4th grade

me and elizabeth nightengale and another kid

her penmanship was

so beautiful i looked at it every day

and she sat upright

while the other kids talked

about her

elizabeth nightingale had short blonde hair

she made me nervous and happy

every day

the most beautiful girl

i had ever seen

talking, the two of us talking

i began to ride my bike across the highway

to elizabeth’s house

after school

we walked and talked

between bursts of energy

i was always catching up to her

mind and she ran

faster than me

we climbed a tree

and straddled a great branch

face to face

and she said:

“do you want to hug?”

the leaves hid us

she was warm and solid

in her denim coveralls

and i felt her body

my first experience with a woman

in 5th grade

they put elizabeth in one class

they put me in another

they separated us

there was only one smart class

in that elementary school

and they knew damn well

she was brilliant

i saw her now and again

in class with the average kids

i noticed her body

she was different

she had grown up

and had little interest in school

she didn’t talk, aloof and closed

and i saw kids give her space

in 6th grade, elizabeth did not show up

her family had left town

elizabeth was pregnant

the father was her father or

her stepfather was the father

someone mentioned a southern state

|

Taps

Charles Hayes

Romantic and sympathetic in its genre, a perfect stand in for the cold and the dead that someone, somewhere, must have loved. Some smidgen of peace it may bring and peace it must keep with them that mourn, their hands clasp away from the necks of those who pipe its tune.

But the dead are more than deaf to its call, the majesty of bursting bombs in air as o’er the ramparts the romantic, gallant, heroes serve up the day’s conquest for the suits at their well laid tables, a place far remote from the stretched and curled ones, never hearing the anthem that pied them to their end, as it laid those tables fair.

Memorials, as the day, are also done, folded flags to bosoms held, shuffled steps to somewhere beyond the blurry vision of it all, go those who will know the dirge anew and never tell.

|

Charles Hayes bio

Charles is an American who lives part time in the Philippines and part time in Seattle with his wife. Born and raised in the Appalachians, his writing interests centers on the stripped down stories of those recognized as on the fringe of their culture. Asian culture, its unique facets, and its intersection with general American culture is of particular interest. As are the mountain cultures of Appalachia.

|

a Sense of Sepia

Copyright R. N. Taber

Confronting the house

where I was born,

so much older now, sadder

(world weary like me);

a poor copy of memory’s

bright front door,

opening up shadowy corners

of the mind

Quite alone in the road

I used to play,

all but empty now, quieter

(time-trodden, like me);

a poor copy of hide-and-seek

and go-karts sure

to bring life to laughter lines

on the brow

Football stadium, home

to comic strip heroes,

looks different now, better

preserved than me

where once shabby red fencing

would sneak me in

to get up a sweat for sandmen

in muddy shorts

Here it was, I would dream

about growing up,

doing things, going places,

being someone else;

a livelier, kinder, inspiration

to mind, body and spirit

than this poor copy preserved

in shades of sepia

Ah, but less of this standing

on time’s misty shore,

letting its fast, outgoing tide

get the better of me...

Rather, I shall bid my ghosts

a fond farewell,

let the Here and Now count

and colour me in

|

A Lesson from the Zen Masters

Jay Frankston

I have been breathing lately

and it’s as if I had never taken a breath before

I’ve been drinking in the air

and feeling the richness of it

and the thirst that it satisfies.

I’ve been breathing with the fullness of my being

and feeling strange connections.

Somewhere deep inside,

I think, I know,

I remember life came to me with my first breath,

a silver flute, silent and pure,

and I’ve been breathing ever since,

silently humming eternity’s hymn,

a continuous connection between me and the cosmos,

a spider’s thread to eternity.

And it feels good this breath awareness

I’ve borrowed from the Zen Masters.

It makes me feel I’ve grown wings

and soon I’ll know how to fly.

|

When the walls are thin

Jay Frankston

When the walls are thin

you can hear the bed heaving

under the sex-laden mattress,

you can hear the neighbors arguing

in violet liquor tones

while the baby cries hysterically

in his cardboard crib.

When the walls are thin

you can feel the hunger of children

in Somalia, or Bosnia

or the ghettoes of L.A.

broken bones around the hearth

and a cold wind under the door.

When the walls are thin

everyone’s problems

become your own

a large wooden cross

over the bed

and a statue of Mary

on the night table.

You must learn to swim

or you drown.

When the walls are thin

you’d better be quiet

or the neighbors will hear you

writing your poetry

in the middle of the night.

|

Jay Frankston Biography

Jay Frankston was raised in Paris, France. Narrowly escaping the Holocaust he came to the U.S. in 1942, became a lawyer and practiced on his own in New York for nearly twenty years, reaching the top of his profession, sculpting and writing at the same time.

In 1972 he gave up law and New York and moved himself and his family to Northern California where he became a teacher and continued to sculpt and write.

He is the author of several books and of a true tale entitled “A Christmas Story” which was published in New York, condensed in Reader’s Digest, translated into 15 languages, and called a Christmas Classic by many reviewers.

El Sereno, his latest novel, is a short epic set in Spain with authentic historical background. It took ten years and two trips to Madrid to complete.

|

Tyrone Leon Jackson Johnson

Christopher Davis

Impress me.

Dress me.

Work me;

Creatively.

Our life all a farce.

You had a loyalty fetish

Or so you said.

“I will always be with you no matter what.”

As narcissistic as you wanna’ be,

You wined me, dined me,

And fucked me

Literally.

You cheated on me

While you left your loyalty with me.

I raised our son;

You gave me grief;

I made you dinner,

You gave me shit.

I brought my heart to bear

Holding it in my hands

Arms extended for days, months, years

Until my arms shook.

Whenever you came home,

It was always temporarily.

You brought hate,

A virus, which denies love-

Hate for our family

For our son

For me

Our happy home destroyed

Because you avoid

Love for you and us.

You took a sledge hammer

And smashed

The sofa

And broke the windows

You broke my heart-

Shaped box

The only thing left intact

Is the freezer which kept your frozen artificial heart in

Next to the chilled beer steins

And old freezer burned ice cream.

Way in the back your heart pulses faintly

As it grows tainted in the coldest, deepest part.

You came home with a virus of heat

Ready to kick us out and fire us

As your family

As your life.

Your substance abuse,

Your cheating,

Your lying,

Created the disease once referred to as the gay cancer

Which grows within you.

You fucked us once,

But we don’t want to get fucked again,

Because we will inherit the HIV-the AIDS

Which are your awards

For your self-loathing

And hatred for us.

You destroyed

And continue to.

RIP my love who is now dead to us

And alive

At the same time.

|

Christopher Davis Bio

Christopher Davis is a poet, teacher, and photographer. He holds a BA. In English and in Pan African Studies; M.A in Education; and an Ed.S in Education. .He has written thousands of poems about life. He is the author of book of poetry entitled Only, If: Volume 1? available for download at the Apple iBook store.

|

A Cloudy Ending

Drew Marshall

The humidity transformed the air

Into contact cement

Sticking to the skin

Seeping into your pores

Changes in the atmosphere

Were palpable

Transforming our DNA

Tropic of solar plexus

In no uncertain terms

We were young

Anointed for a mission

To change the world

With peace & love

And force, of idealistic will

At best

We made a small dent

Near the chink, in the amour

The rank & file

Bucked the power

They paid the price

There are no warning signs

There are no boundaries

|

Hymie and Nat

Drew Marshall

Hymie and Nat, ran the local delicatessen

During the summer, they wore short sleeve shirts

The delicatessen, didn’t have air conditioning

Everyone could see, the numbers, tattooed, on their wrists

The brothers had been interviewed, on a local news station

Hymie was a compact, positive, bundle of energy

Happy, smiling, quick with a joke

Extending credit, to anyone that bothered to ask

Nat wasn’t so lucky

He was out of it, grim, never smiled

Who knows what nightmares, haunted Hymie?

His wife and son died, in the camps

Hymie and Nat closed up shop, about ten years ago

They took part of the neighborhood’s character, with them

|

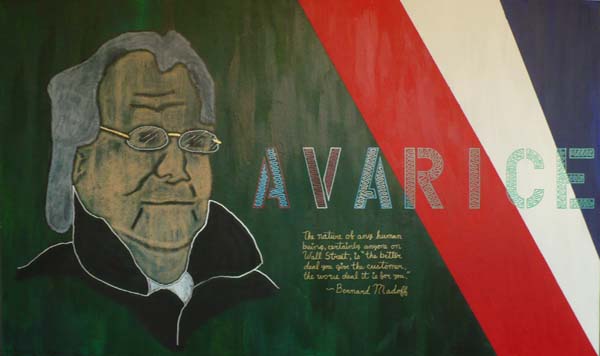

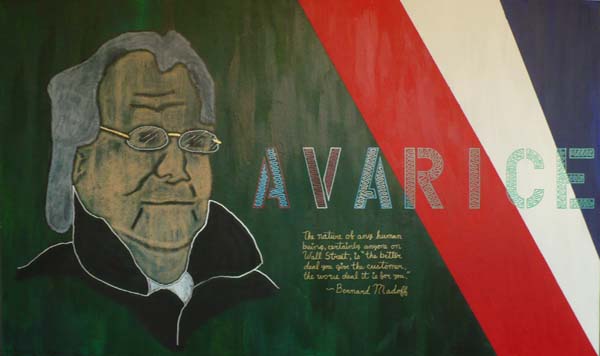

Merely a Symptom, painting by Aaron Wilder

Inconvenient Facts

Drew Marshall

When alone, listening to

Chopin’s, Nocturne # 8 in D Flat Opus 27 # 2

I sincerely believe

If man can imagine and invent

A grand piano

Compose this piece of music

Perform, and most preciously, record, it

Then we do have marvelous potential

Redeeming qualities, well worth cultivating

Yet the Nazi’s, were kind to animals

Loved this music too

When listening

It’s easy to momentarily, forget

These inconvenient facts

|

The Krafft-Ebing Poems

Bill Yarrow

Case #106

when she was about ten years old

she thought that her mother no longer loved her

so she put matches in her coffee

to make herself sick

that she might thus excite

her mother’s affection for her

Case #88

on account of his impotence

the patient applied to Dr. Hammond

who treated his epilepsy

with bromides

and advised him

to hang a boot over his bed

imagine his wife to be a shoe

and to look at it fixedly during intercourse

Case #8

as a child he was not affectionate

and was cold toward his parents

as a student he was peculiar

and retiring, preoccupied with self

he was well endowed mentally and given to much reading

but eccentric after puberty

alternating between religious enthusiasm

and materialism

now studying theology

now natural sciences

at the university his fellow students

took him for a fool

for he read Jean Paul

almost exclusively

Case #89

on his marriage night

he remained cold

until he brought to his aid

a picture

of an ugly woman’s head wearing a night cap

whereupon coitus was immediately successful

Case #36

she must stand at the window

awaiting him with her face done up

and on his entrance into the room

complain of severe toothache

he is sorry for her

asks particularly about the pain

takes the cloth off

and puts it on again

he never touches her

yet finds complete sexual satisfaction in this act

Case #55

on their wedding night

he forced a towel and soap into her hands

and without any other expression of love

asked her to lather his chin and neck as if for shaving

the inexperienced young wife did it

and during the first weeks of married life

was not a little astonished to learn

the secrets of marital intimacy in this way alone

Case #102

the patient in a circle of erotic ideas

grows more and more peculiar

he avoids the society

of women

associates with them

only for the sake of music

and only when two witnesses

are with him

Case #83

his dreams are filled

with aprons

This poem appears in Incompetent Translations and Inept Haiku

(Cervena Barva Press 2013) and Blasphemer (Lit Fest Press 2015).

|

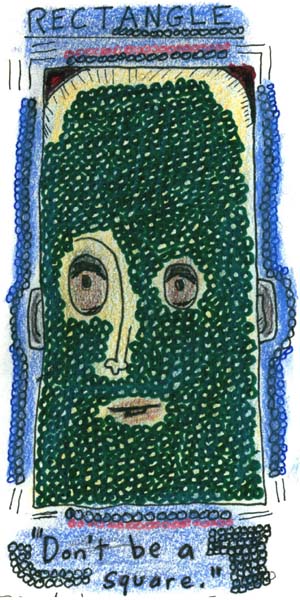

of independence

or freedom

Janet Kuypers

5/31/15

So it seems you cram us in here

like we’re sardines.

How many of us have you crammed in here

before you send us on our way?

Strap us in, make sure

we don’t get any strange ideas

of independence or freedom

(‘cause really, you wouldn’t want us

to think for ourselves)...

Strap us in, compartmentalize us —

but the thing is, you thought

I was just like everyone else,

that I’d just sit back and take it.

These sardines around me

seem totally complacent —

what have you told them

to make the so subservient?

Well, maybe you didn’t get it before

but I’ll take a sledgehammer to your plans.

I’ll shatter that glass ceiling

and that two-way mirror

you watch us through.

I don’t care where you think

you’re taking us,

and I no longer care

if you’re sending us away.

I didn’t sign up for this ride,

and being crammed in here

is making me nauseous.

Don’t make me throw up

before I start my revolt,

because whether or not

you think we’re sardines, and want

cram us away like we’re nothing,

just remember:

I’m bigger than my ego lets on

and I’ll take whatever makeshift

weapon I can find, to break free

of how you think we should be.

|

untitled 6/11/15

Janet Kuypers

6/11/15

two-tweet poem

I was at the bar

approaching 5PM

& I looked out the window

and saw a grey SUV

that looked like a Jeep.

& I thought

it could have been you.

I knew it wasn’t,

but it made me smile.

The thought of you,

coming to me.

|

ever leave me

Janet Kuypers

6/24/15

if death ever consumed you

if your soul were ever to leave

if there was something out there

insidious enough, evil enough

to snuff you from this earth

and force us to go on without you

well, what would I do

as you departed, I would hold you

until your heart stopped beating

and then I would hold you tighter

until your brain no longwr functioned

because I would want

your thinking mind to know

that I would hold you fiercely

and never let you go

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem ever leave me live 7/25/15 on Chicago’s WZRD 88.3 FM radio (Cfs)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem ever leave me live 7/25/15 on Chicago’s WZRD 88.3 FM radio (Cfs200, FlCrSat)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers (wrapped in VHS tape) in her 8/14/15 show “Farewell Chicago” in her final scheduled feature at Poetry’s “Love Letter” (while living in Chicago) in Chicago (Canon Power Shot), with her poems

Chicago,

Breaking Their Heart,

change (2015 edit),

Planting Palm Tree Seeds,

Shared Air,

Other Souls, and

ever leave me.

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers (wrapped in VHS tape) in her 8/14/15 show “Farewell Chicago” in her final scheduled feature at Poetry’s “Love Letter” (while living in Chicago) in Chicago (Canon Power Shot), with her poems

Chicago,

Breaking Their Heart,

change (2015 edit),

Planting Palm Tree Seeds,

Shared Air,

Other Souls, and

ever leave me.

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers (wrapped in VHS tape) in her 8/14/15 show “Farewell Chicago” in her final scheduled feature at Poetry’s “Love Letter” (while living in Chicago) in Chicago (Canon fs200), with her poems

Chicago,

Breaking Their Heart,

change (2015 edit),

Planting Palm Tree Seeds,

Shared Air,

Other Souls, and

ever leave me.

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers (wrapped in VHS tape) in her 8/14/15 show “Farewell Chicago” in her final scheduled feature at Poetry’s “Love Letter” (while living in Chicago) in Chicago (Canon fs200), with her poems

Chicago,

Breaking Their Heart,

change (2015 edit),

Planting Palm Tree Seeds,

Shared Air,

Other Souls, and

ever leave me.

|

Download poems in the free chapbook

Farewell Chicago

of this & other poems read 8/14/15 at a live Chicago show

|

|

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006.

She sang with acoustic bands “Mom’s Favorite Vase”, “Weeds and Flowers” and “the Second Axing”, and does music sampling. Kuypers is published in books, magazines and on the internet around 9,300 times for writing, and over 17,800 times for art work in her professional career, and has been profiled in such magazines as Nation and Discover U, won the award for a Poetry Ambassador and was nominated as Poet of the Year for 2006 by the International Society of Poets. She has also been highlighted on radio stations, including WEFT (90.1FM), WLUW (88.7FM), WSUM (91.7FM), WZRD (88.3FM), WLS (8900AM), the internet radio stations ArtistFirst dot com, chicagopoetry.com’s Poetry World Radio and Scars Internet Radio (SIR), and was even shortly on Q101 FM radio. She has also appeared on television for poetry in Nashville (in 1997), Chicago (in 1997), and northern Illinois (in a few appearances on the show for the Lake County Poets Society in 2006). Kuypers was also interviewed on her art work on Urbana’s WCIA channel 3 10 o’clock news.

She turned her writing into performance art on her own and with musical groups like Pointless Orchestra, 5D/5D, The DMJ Art Connection, Order From Chaos, Peter Bartels, Jake and Haystack, the Bastard Trio, and the JoAnne Pow!ers Trio, and starting in 2005 Kuypers ran a monthly iPodCast of her work, as well mixed JK Radio — an Internet radio station — into Scars Internet Radio (both radio stations on the Internet air 2005-2009). She even managed the Chaotic Radio show (an hour long Internet radio show 1.5 years, 2006-2007) through BZoO.org and chaoticarts.org. She has performed spoken word and music across the country - in the spring of 1998 she embarked on her first national poetry tour, with featured performances, among other venues, at the Albuquerque Spoken Word Festival during the National Poetry Slam; her bands have had concerts in Chicago and in Alaska; in 2003 she hosted and performed at a weekly poetry and music open mike (called Sing Your Life), and from 2002 through 2005 was a featured performance artist, doing quarterly performance art shows with readings, music and images.

From January 2010 through August 2015 Kuypers also hosted the Chicago poetry open mic at the Café Gallery, while also broadcasting the open mic’s weekly feature / open mic podcast (and where she sometimes also performs impromptu mini-features of poetry or short stories or songs, in addition to other shows she performs live in the Chicago area).

In addition to being published with Bernadette Miller in the short story collection book Domestic Blisters, as well as in a book of poetry turned to prose with Eric Bonholtzer in the book Duality, Kuypers has had many books of her own published: Hope Chest in the Attic, The Window, Close Cover Before Striking, (woman.) (spiral bound), Autumn Reason (novel in letter form), the Average Guy’s Guide (to Feminism), Contents Under Pressure, etc., and eventually The Key To Believing (2002 650 page novel), Changing Gears (travel journals around the United States), The Other Side (European travel book), the three collection books from 2004: Oeuvre (poetry), Exaro Versus (prose) and L’arte (art), The Boss Lady’s Editorials, The Boss Lady’s Editorials (2005 Expanded Edition), Seeing Things Differently, Change/Rearrange, Death Comes in Threes, Moving Performances, Six Eleven, Live at Cafe Aloha, Dreams, Rough Mixes, The Entropy Project, The Other Side (2006 edition), Stop., Sing Your Life, the hardcover art book (with an editorial) in cc&d v165.25, the Kuypers edition of Writings to Honour & Cherish, The Kuypers Edition: Blister and Burn, S&M, cc&d v170.5, cc&d v171.5: Living in Chaos, Tick Tock, cc&d v1273.22: Silent Screams, Taking It All In, It All Comes Down, Rising to the Surface, Galapagos, Chapter 38 (v1 and volume 1), Chapter 38 (v2 and Volume 2), Chapter 38 v3, Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite (Volume 1, Volume 2 and part 1 of a 3 part set), A Wake-Up Call From Tradition (part 2 of a 3 part set), (recovery), Dark Matter: the mind of Janet Kuypers , Evolution, Adolph Hitler, O .J. Simpson and U.S. Politics, the one thing the government still has no control over, (tweet), Get Your Buzz On, Janet & Jean Together, po•em, Taking Poetry to the Streets, the Cana-Dixie Chi-town Union, the Written Word, Dual, Prepare Her for This, uncorrect, Living in a Big World (color interior book with art and with “Seeing a Psychiatrist”), Pulled the Trigger (part 3 of a 3 part set), Venture to the Unknown (select writings with extensive color NASA/Huubble Space Telescope images), Janet Kuypers: Enriched, She’s an Open Book, “40”, Sexism and Other Stories, the Stories of Women, Prominent Pen (Kuypers edition), Elemental, the paperback book of the 2012 Datebook (which was also released as a spiral-bound cc&d ISSN# 2012 little spiral datebook, , Chaotic Elements, and Fusion, the (select) death poetry book Stabity Stabity Stab Stab Stab, the 2012 art book a Picture’s Worth 1,000 words (available with both b&w interior pages and full color interior pages, the shutterfly ISSN# cc& hardcover art book life, in color, Post-Apocalyptic, Burn Through Me, Under the Sea (photo book), the Periodic Table of Poetry, a year long Journey, Bon Voyage!, and the mini books Part of my Pain, Let me See you Stripped, Say Nothing, Give me the News, when you Dream tonight, Rape, Sexism, Life & Death (with some Slovak poetry translations), Twitterati, and 100 Haikus, that coincided with the June 2014 release of the two poetry collection books Partial Nudity and Revealed.

|

Glossolalia

Eric Allen Yankee

Even the donkeys and elephants

Study ballistics now.

They donate our money to

Global executioners

Who have encrypted their own

Blood spatter mission statements

And appear even to each other

As wolfish believers

Rolling ecstatically down

Empyrean highways

Etched into the drought

Of gaping white fences

That once ruled plain folks

Dreams.

Our brains now pirouette

To the tune of addiction

And the pain of being.

They speak in tongues

And call themselves

Our masters.

They believe

We can’t hear,

But we know they

Can be

Easily interpreted

As they tremble and yowl:

We don’t need you anymore.

|

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

|

Christmas in Switzerland

Dean Jones

Was something drawing me back to the country for another family Christmas, and to enjoy the memory of Christmases past? I couldn’t decide whether it was the anticipation of seeing the Alps, enjoy a quality of living I had never experienced, or getting away from the life I was leading in England. Other than the visits to North Wales over the weekends to climb and scramble on the peaks of Snowdonia National Park, I was slowly becoming jaded and tired of work and the effect it was having on me. So a break was just I needed, and where better than the land of efficiency and where a plan is always essential, almost a Swiss tradition?

When I flew into Switzerland I was treated to a fantastic view of the mountains in the distance prior to landing in Zurich. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the Swiss Alps. It was Mont Blanc in France. The airport has grown in recent years with a new terminal and excellent facilities. This should be no surprise to anyone who has visited the country (only the best in Switzerland). The airport has its own railway station, which is located underground (something you might see in a James Bond film), and is connected to Zurich and the majority of the larger Swiss cities. As soon as you stepped of the plane, efficiency was in the air, even the weather was on time.

On this occasion, I was driving from Portsmouth to Zurich via the Channel Tunnel to spend Christmas with my family. My grandparents moved to Zurich twenty years ago, and we held a family Christmas there for the past eight years.

I’m not sure if it’s British stubbornness, but why oh why can’t everyone drive on the same side of the road? Throughout my time spent on the continent, I had to contend with stretching to the left had side of the car whenever I had to pay parking fees and tolls. However, I was lucky on the drive down, because the French toll booths were free. The workers who manned the booths were on strike, and taking an extended Christmas break. They were standing by the booths holding an enormous banner and waving me through. Having seen the GB sticker on my car I was treated to a demonstration of various French hand signals.

The Channel Tunnel runs from Dover to Calais, from which I traveled to Paris on the ring road. The road didn’t offer many views of Paris, although I did glimpse the Eiffel Tower from a distance. I left Paris, heading east to the French/German border at Strasbourg, and then south to Basel and, finally, heading east to Zurich.

At the Swiss/German border, despite my car being full up with Christmas gifts in varying boxes and packages, I was not stopped. The mere thought would have sent a shudder down the spine of a Swiss Customs official. Oh no! One got through! However, it appeared that their attention was drawn to a van belonging to a reputable Swiss bank (well, Swiss bank) trying to return valuables to their Jewish owners.

I had arrived and was looking forward to the world-renowned Swiss hospitality. Even though I had been there before, it took a while to locate my grandparent’s house in Zurich, even though it was close to the Opera House. To say their place was big is a major understatement. At the front door they sold maps, and looked for a generous donation to the ‘Not So Well off Swiss Bankers Association’. What was most annoying was the number of tourists who would ring the door bell asking if we had any spare rooms available, especially at Christmas. However, the family didn’t plan to spend much time there, especially on the weekends, in which we would put on our hiking boots and travel to the mountains to hike, eat rosti and down a beer or two.

I quickly hauled my suitcase and gifts up to my room on the third floor. The room came with the option of a financial advisor to plan my spending during my visit. My grandparents employed a landlady/concierge who was helpful and would prove to be extremely useful when dealing with the bureaucracy for which Switzerland is world famous. This included a visit to the local police station to determine whether I was financially viable to be able to park in a metered road.

Every week my grandparents sent the landlady to Germany with a shopping list as the food is cheaper over the border. Strangely enough, my second cousin Hans used to come to Switzerland every week to do his shopping. He would walk into the closest grocery and claim that unless he got some service, he would send in the Panzers. He is current receiving treatment at one of Switzerland’s finest sanatoriums for the delusional and the generally over optimistic.

When travelling in Zurich on the trams and local trains, you realize that death and taxes are not the only two things that can be guaranteed in life. The other is that Swiss trains would always arrive and depart on time. It was a badge of honor, and I believe the word “late” is one of those words adolescent Swiss boys look up in the dictionary to find out what it means. It wouldn’t surprise me to hear that train engineers had thrown themselves off the nearest alp if their trains were 30 seconds late.

We gave a watch to our cousin Fredrick, who, upon opening the present, rushed out the door and raced to the train station to synchronize his watch to ensure it was set at the right time. He was determined not to be the laughing stock of this school on return from the Christmas holidays by being the only one with an inaccurate timepiece.

When visiting other countries you come across interesting activities. One celebration that focuses on the common standards of different nations is the Swiss/Japanese train drivers club, which has vowed to ensure that trains run on time. The club is made up of train drivers and conductors. It is the only club I know in which “kamikaze” is in the membership terms. One Christmas, the train delivering club members to Zurich was late by five minutes. Before you could say “bonsai” the train carriage was a blood bath with the club members fulfilling their sacred duties of dying rather than be an accomplice to delayed public transport.

The first year our family met in Switzerland we brought a tree so big we needed the fire service to put the star on the top of the tree and needed a machete on Christmas morning to get to the presents. It wasn’t until we chopped it down on January 6 that we discovered there were still a number of gifts that weren’t opened. Placing the lights on the tree was a monumental effort, taking a team of experienced Sherpas two days to scale the heights of the lower branches and pave a way to the higher branches of the tree. Then, with some trepidation, family members were sent up one by one. It became one of the most famous ascents in the history of Christmas trees. On the way down, we found a bird nesting for the winter and a couple of squirrels protecting their nuts.

As well as the overly decorated Christmas tree, one tradition that I brought over from the UK was the grand tradition of leaving two mince pies (fruit, not meat, for those not in the know) and a glass of whisky for Santa. This backfired one Christmas, when we left the bottle. We don’t know who drank the bottle dry, but the individuals looking like death at six in the morning with a headache was a strong candidate. The best way to recover was taking a walk to breathe in the clear Swiss air, and relive last night’s meal.

While I had studied German, any attempts to use the language were usually met with a response in English. This always astonished me. Not that the Swiss could speak English, but the surprised tone in their voice that I had made it out of Britain and traveled as far as central Europe. This was usually expected of the Germans. I put it down as their surprise I could live without a fish and chip shop for any length of time. The pride one feels in being able to speak a foreign language is limited by the ability of the foreigner to listen to you struggle and destroy their language. The English approach appears to be the classic, speak loud and slowly, and then everyone will understand you.

The tradition of carol singing was as prevalent today as it has been for many years. However, the response tended to be more negative; including the throwing of water, hurling of abuse, and if they were really bad, money so that they would go away. What a wonderful way to raise money for those in need, including failed Swiss bankers. One year, when the carolers arrived, we positioned them over the cellar door in the garden and when we had too much, we pulled a leaver and they fell like a brick into the cellar. We would threaten to release them on an unsuspecting town. My family was given the key to the city.

The key to a good Christmas is the food. There are many Swiss traditions and local delicacies to enjoy; and many more if shopping in Germany. It really is cheaper. My grandmother would spend the days leading up to Christmas baking, which included plates full of biscuits. The biscuits would be the shape and pattern of Swiss currency. They are so life-like that they have become legal tender in some of the more remote valleys of Swiss Alps.

Crisp new layers of snow would welcome hikers, climbers, along with the cold weather denial club. They meet every year to snowboard and ski with nothing but a small slip of material, generally wrapped around their heads. I believe they defined the phase, “freezing your nuts off.” Although a few squirrels may lay claim to that saying.

The abundance of snow makes the Christmas holidays much more special. You could take a sleigh ride or go snow shoeing or launch yourself down a hill with two pieces of wood strapped to your feet, a common activity. The snow does not bring traffic chaos as you see in other towns in other countries. In fact, every September cars line up to have their tires changed from summer to winter, up to the point that the local law enforcement ensured that tires have been changed or the full force of the law will be on you. However; there is a lot to be said about a stay at a Swiss prison. Run like a well funded hotel, the guests (inmates) are given complementary slippers, robes and three substantial meals a day. Also, long-term inmates are given the opportunity to buy their own cells.

And finally, as they say on the news, for foreigners in Switzerland, there are a variety of experiences, none more so than during the Christmas holidays. So enjoy your stay there and be amazed to the point of incredulousness.

|

Elmer

Liam Spencer

The guy was a total asshole in every way. He was our thirteenth acting manager in eighteen months. This was his last chance. He had been bounced out of everywhere else for his temper and irrationalities.

There was no way to ever get through to him. He would make up his mind about things, no matter the facts. There was a severe disconnect in his mind. It was your fault no matter what.

He was a short little man with a very heavy Asian accent. He seemed to barely understand English at times. No matter what anyone said, he was outraged. If he asked you a question, he gave the third degree with a high pitched;

“HUH?! HUH?!” Ear shattering.

He screamed at everyone daily, often hourly, no matter how hard they worked. It was a culture of fear and bullying. Supervisors scurried to try to satisfy his fantasy demands. Union stewards prepared grievance after grievance. Costs were mounting.

Everyone counted down the days until he was gone. It couldn’t come too soon.

I was on light duty with severe injuries to my foot and ankle. Surgery was likely. Every step was pain. I still hustled, and was as fast as everyone else at things I was able to do. The acting manager screamed at me for having said injuries, threatening to fire me repeatedly.

Short on vehicles, I was stuck in the office with nothing to do. It was hell. I had to look busy. There was no escape.

The acting manager gathered the supervisors and clerks, and began screaming at them. His accented screams echoed the building to headache inducing levels. I was to his back, so he couldn’t see me as I pretended to have work to do.

On and on he screamed to faces of concrete and sorrow. What a life. What a job. Where do we go so wrong as to face such a horrible fate?

And then...

“and every time I try to talk with you, you running around like rabbits!”

Think about that with such a heavy accent...

“Wunning awound wike wabbits?!”

Our acting manager was Elmer Fudd.

I had to fake a sneezing attack and go outside. I made it less than ten feet before exploding in laughter. I hated to make fun of his accent, but in the context of his screaming at people, combined with that phrase, it was too much to bear.

I was laughing too hard to breath. I saw Bug Bunny “wunning awound.” I saw Elmer Fudd chasing him.

I saw the acting manager, when he was lurking around looking for someone to scream at, as saying “Be wery, wery quiet, I’m hunting wabbits.”

On and on I laughed. Tears actually began showing. I could hardly breathe.

I hid under the dock, choking on the smoke I had lit, still laughing.

“Wunning awound wike wabbits.”

“Kiww the wabbit, kiww the wabbit, kiww the waaaaaaabbbbbiiitttt.”

Hahahahahahahaha

Eventually I got my composure. I went inside the building. The screaming was over. I rushed to my case and pulled paperwork out and prepared to do more pretend work.

A voice rang out.

“MERCER!”

There he was, full of fury.

“It’s you TOO, you know.”

“What’s that?” (Yeah, I almost said “What’s up, Doc?”)

“It’s you too. Every time I try to talk with you, you’re wunning awound like a wabbit.”

I began my fake sneezing attack. It was the only way. The only way...

“What’s a matter? You sick?! HUH?! HUH?! Always sometime with you. Always something.”

He walked away shaking his head.

A clerk walked up to me smiling. She saw that I was laughing.

“Are you ok?”

I smiled to the point of laughter.

“Yeah, I’m just one of us wascally wabbits. Hahahahahahaa”

Barely subdued laughter exploded.

It was another day in the life of a working class wabbit being hunted by Fudds.

|

Lake City

Liam Spencer

It was a miserable neighborhood. Drugs and thugs ran around everywhere, but only for a three block radius. Outside of that circle, everything was fine, even kind of nice. Yet, there we were, living smack in the middle of misery.

The place was the now ex wife’s idea. What she wanted, believe me, she got. There would be no arguing. She needed drama. Lived for it. Not even her own family dared to take her on.

The only time there was no misery was when I was at work. I counted down the hours until I’d get to return to work.

It had been a long road back to getting on our feet. Our restaurant had failed. Largely it was because she had decided to not run the place. The restaurant had been a gift from her wealthy father to her, hoping she’d become grounded enough to settle down and stop being as insane.

With the restaurant having lost so much money, I ended up in bankruptcy. I took that hit myself, willingly, rather than not being able to live the down horrible conditions she endured. Putting it all on myself would partially keep her off my back. I had escape in mind. Escape from the miserable marriage. The only way to appease her and her family in that eventuality was to take the hit myself.

Doing so meant giving up my car. I had depended on it for mileage payments. Those payments were fully half of my income. We were poor. Dirt poor. I saved four hundred and found an old Honda Civic on Craigslist with low miles. It was old and rotted. Parts would fall off as it drove. My route was over three hundred miles a day. That meant a lot of parts falling off on the freeway. It was the only way to restore our income.

I dreadfully headed home one night. I knew her fury awaited. Not exactly a religious man, I found myself praying for help to get through the night. I turned on to a side street. A guy who obviously was high on something staggered out in front of my car. I stopped well in time. He passed by, giving me the finger.

I took a long, deep breath before making the right turn onto our street. Fuck. Here we go.

Just before I turned into the driveway of the apartment building, flashing lights went off. A police SUV roared up behind me. I pulled over just five feet from the parking lot entrance.

A tall, muscular cop came to my window. There was a giant sneer across his face.

“Keep your hands where I can see them. What’s your name?”

I looked at him puzzled and told him.

“How many warrants are out for you?”

I looked at him more puzzled.

“None, of course. Why would there be warrants for me? I’m just coming home from work. I still have my uniform on.”

“Yeah. Heard it all before. License and registration. NOW.”

I handed him my license first, then registration. His flashlight reflected off both and lit his increased scowl. His eyes of rage showed clearly.

“You HOPE there’s no warrants! I’ll find them, then you’re DONE!”

His tone set me off.

“There are NO warrants on me. I actually work for a living. See for yourself.”

After a long, long while, he came back to my window. Now his face was pure hate and rage.

“Here’s your fucking shit back. Don’t you EVER let me see you here again!”

“I live right here. I’ll be here every day, coming home from work. Every day.”

“Not if I catch you.”

He stormed back into his vehicle and tore off.

The parking lot was full again, so I would have to park a few blocks away and walk the dangerous streets, all in order to get bitched at all night by my wife. Great. What a great life I had found my way into.

I parked the old beaten up car along a side street. At least the damn thing was dependable. A Honda, after all. I got out of the car, and turned. A staggering drunk came up and demanded my wallet. He had a knife. Before I could answer, he tried to come at me and fell. He began puking, and then fell in it all. I walked past grumbling about asshole cops never being around when needed.

Shouting erupted a half block away. A huge man appeared behind people that were running from him. He was well known in the neighborhood for getting fucked up and doing crazy things, whether throwing shit or even shooting his guns at whatever.

People scattered as bullets fired. I jumped back and hid behind my car. All the vehicles along that street where getting shot up, including mine.

“You think you’re safe now? I have my other one here too!”

More shots seemed to go everywhere. On and on.

I lit a smoke. Fuck it.

Eventually he went back inside, yelling profanities about how lucky we all were that he ran out of bullets. I quickly walked home, only pausing to take a deep breath to brace myself before facing the real hell that awaited me.

|

whacking off heads

Fritz Hamilton

WHACK!

WHACK!

WHACK!

“What is that I hear, Luca?”

“Fred, what you hear is the Islamic State whacking off heads.”

“It seems that we too are standing in the line of the whacked.

“Indeed we are, Fred. The last whack we hear will be the knife decapitating us.”

“Since you are in line just before me, Luca, I’ll be cognizant of you being whacked, but you’ll be beyond that & won’t be conscious as I’m whacked.”

“That seems to be so, Fred.”

WHACK!

WHACK!

WHACK!

“They’re getting closer, Fred.”

“Yes they are, Luca. Prepare to meet thy maker.”

“I’m going to give Him a piece of my mind, Fred. This is a shitty way to go.”

“I wonder how many of us get to pass pleasantly in our sleep, Luca.”

“That’s a moot question, Fred, at least for the likes of us.”

“I wonder how many of our fellows truly likes us, Luca. I think most just don’t give a shit that we’re whacked or not. It’s kind of like seeing the garbage removed. We appreciate it, but it’s not like a good quiz show. We’re whacked, but so what?”

WHACK!

WHACK!

“How do you feel now, Luca? They’re almost upon you. You can even smell the blood.”

“I wonder if I’ll have a split second to smell my own blood, or if it’s all over as soon as the blade penetrates.”

“I doubt if you’ll have time to inform me, Luca, but it may be a quick call.”

“If you have anybody to call, Fred, you’d better do it now. Did they leave you your cell phone?”

“I never had a cell phone.”

“Then you’d better shout as loud as you can, Fred.”

The Islamic State arrives, big head cutters with sharp knives bleeding at their sides. They position Luca with his head sticking out. He is gasping & whimpering as he should. This isn’t child’s play. They are singing patriotically like, “Give me a head to whack. I’ll put it in a sack. It will rot black, & stink to holy Hell. We wish him well, but he won’t come back, but give no slack. Say goodbye & give him a whack,” & in that sad condition, he’s off for perdition. Bye-bye, fool, you smell like the stool you shit in yr pants. Now here come the beetles & the ants, as you become a ghoul. Bye-bye, fool.

Over & over they sing this song, & before long, they cut off yr dong. Bye-bye, fool! They bury you in yr stool. Bye-bye, ghoul!

NEXT!

That’s me!

|

hanging from the bridge

Frtiz Hamilton

“Well, what’s that hanging from the bridge?”

“Look twice, Luca. They’re people.”

“They’re wearing uniforms, Fred.”

“American uniforms. They’re army, maybe marines.”

“So who hanged them?”

“People who don’t want us here.”

“But Fred, aren’t we saving them from themselves?”

“Not anymore.”

“Aren’t we going to cut them down?”

“Of course, & send them home to their loved ones in the states.”

“Then what?”

“We’ll send them more Americans to save them from themselves, & they’ll hang them from other bridges.”

“Those aren’t bridges to peace, Fred.”

“No, they go straight to Hell, paved with good intentions, Luca.”

“That’s what counts.”

“I’m glad it counts, Luca. All I count are eight hanged Americans.”

“So what can we do, Fred?”

“We can look on this divine comedy until they hang us too.”

“Who’s laughing at the comedy?”

“God the divine.”

“Then shouldn’t we be laughing too?”

“If it turns you on, Luca. Laugh yr guts out until you too swing from the bridge. When they send yr death notice back home to Mommy & Daddy, they can say you were laughing till the final curtain. Then they’ll get a special package of yr bones.”

“Will they still be laughing?”

“Why not? What else can they do?”

|

Cargo

Charles Hayes

First published Vol. 05 No. 11 eFiction Magazine.(Feb. 2015)

In the quiet pre-dawn darkness along the Seattle waterfront, a cloaked and covered lone figure scans the harbor like a spy from a bygone day. The fedora is his one capitulation to eccentricity. The trench coat, still a common sight in this town, belonged to his father. Back when he was young and a new immigrant he adopted the hat and took on the coat after he became hooked on old Humphrey Bogart movies. That was nearly thirty years ago and many times since then these things have served well as his umbrella. And, unlike an umbrella, they are not easily forgotten when temporarily laid aside. Never married, Bo Chen spends most of his time and efforts on a small business and apartment in Chinatown but, sadly, it doesn’t keep him from being lonely. The melancholy nature of the empty bay seems to match his own mood as forlorn thoughts creep around in his head.

At the nearby wharf, under large spotlights hanging from the overhead cranes, the container ship from Shanghai is secured and readied for unlading. Bo has been tracking it and his container of expensive green jade figurines for the past two weeks. Several purchases at his shop hinge on this delivery, not to mention the investment he has in it.

Mental calculations tell him that the container with his merchandise should reach his warehouse in about two days. Logging this into his smart phone calendar, he turns to leave, then notices that the rising sun over the Cascades is about to set aglow the whole wharf area. Brilliantly painted cranes, reaching out and canted over the ship’s length, turn a fiery color, like a row of red mantis ready to feed. The scene lifts Bo Chen’s heart. Doing business in Seattle is a pleasure. Once the unlading begins he knows that it will continue around the clock until it is done. It is still early and all is as it should be. Tugging his fedora, Bo Chen heads for the public market along the seawall. He still has time to have some tea and one of Sum Lee’s steamed pork buns before opening his shop.

A loud hiss of air brakes makes Bo jump when the diesel rig backing his container stops just shy of the warehouse loading platform. This is the big day he has looked forward to. Anticipation, combined with his efforts to make sure that there are no mistakes right up to the end, have his already high-strung nerves more on edge than usual. After inspecting the bill of lading and checking the container locks and seals Bo approaches the driver.

“Everything seems to be in order, you can unhook and drop it right here.”

The driver seems a little surprised. “Don’t you want to open it up and check the contents?”

“I’ve been doing business with these people for a long time,” Bo says. “The locks and seals are good. It’s fine. I’ll do the inventory later. You can go.”

The driver shrugs his shoulders, hops down from his cab, quickly unhooks and drops the container on its fore pods, then heads back to the port to wait in line for his next container.

Bo watches him disappear into the commercial So Do traffic before starting to unlock the container and break the seals. Finally he has possession of his wares. In his excitement he fumbles and bangs the first lock several times while removing it. Reaching to remove the second lock, he freezes when he hears tapping inside the container. His heart pounding in his ears, Bo doesn’t move for many seconds. The tapping comes again. Bo quickly gathers himself, taps out a simple cadence, and waits. Almost immediately the cadence is repeated. Rattled and scared, Bo uses his sleeve to wipe his sweaty brow before he removes the final lock. Cautiously, he disengages the latch and pulls the doors open. Immediately he is repelled several feet by the stench. But not before he sees a person lying on a thin pad in the space nearest the door. Also there is what appears to be the bottom part of a 55 gallon oil drum that has been cut off and made into a toilet. It is half full. An almost empty plastic container of perhaps 15 gallons has been used to hold water. Food wrappers litter the rest of the vacant space except for one large cardboard box that contains a few unopened wrappers of some kind of jerked meat and a few rotting fruits and vegetables. Boxes of jade figurines occupy all the rest of the shipping container and have been more or less walled off with mesh from the small area near the door. Except for some dried feces that must have splashed up on the boxes near the toilet, all seems to indicate that the cargo shipped undisturbed.

Still scared, Bo stares at the unmoving figure lying near the door. Dressed in filthy clothes with what looks like a large bloodstain on the front of the trousers, it is hard to tell if it is a man or a woman. Not knowing what to do, and unsure about getting involved, he finally decides that he should get closer and try to see if this person is injured. But before he can do this the prone figure suddenly raises an arm over their eyes, blocking the light, turns their head toward him, and says in Chinese accented English, “Do you have some extra pants? I forgot to bring tampons.”

Hau Ming, in her mid thirties, was born in Shanghai to parents who later died from abuses that they had suffered during the cultural revolution, leaving her to be raised and educated in a Catholic orphanage. As she grew and matured Hau showed great promise with her catechism as well as her academic subjects, prompting the nuns to send her on to be educated in one of the better Shanghai universities. There, near the end of her studies, and to the dismay of her patrons, she met and married another bright student. They produced one child, a girl, not long after they wed. Tragically, however, one night during the Lunar New Year celebration a large van loaded with fireworks exploded during the traditional New Year’s Lion and Dragon Dance. Several in the crowd were severely hurt. Three were killed outright, including Hau’s husband and little girl whom had been standing next to the van. Hau Ming was just returning with refreshments and was further away from the blast. She received serious burns to her right arm and a lesser burn to the right side of her face. The intense flash of heat singed and burned most of her clothes, leaving her lying and smoldering in the street like a freshly doused fire log.

When her wounds healed and the grief for her loved ones became less painful, she decided that life was too short to wait for the auspicious. Now was the time to risk a new life. Her old one was surely gone.

The aroma of the roasted teriyaki chicken from Dong Chang’s Barbecue Shop tells Bo how hungry he is. His mouth waters as he climbs the steps to the apartment over his shop via a separate outside entrance. Sniffing the sweet smoky smell of the barbeque, he wonders if he should have bought two. Hau Ming, a few pounds lighter than before, has not failed to clear her plate for the past two days—ever since he brought her home from the container. It was not hard for him to do the right thing for someone in such a helpless position. He was always big hearted despite the face he put on during his business actions. Bo Chen gave over his bedroom and most of his bath and slept on the couch. Falling asleep while watching TV had always been easy for him anyway. That was the easy part. Getting her clothes was a little different. With no experience buying women’s clothes, he had to rely on sales help from the people at the little used clothing store down the street. When Hau first appeared in fresh clothes Bo plainly saw what an impressive and feminine person she was. The cloth and cut of the Asian apparel accented the intelligent bone structure of her face and complimented her willowy figure. A little taller than Bo, she looked nothing like the starved figure he had first seen on the floor of the container. Almost immediately he began to feel a little change in his moods as well. Helping her pleased him.

After knocking on the door at the top of the steps, Bo unlocks and enters the apartment. Still preoccupied with his thoughts about the pleasant changes in his moods, he at first doesn’t recognize his own place. The scent of a sandalwood joss stick accompanied by the soothing twangs of pipa music stroke his senses. Discarded on a small seat in the bay window that overlooks the street, Bo notices the jacket to one of his old lute albums. Obviously Hua Ming has mastered his ancient turntable stereo. And the apartment looks so much neater and cleaner than he ever keeps it. On the small dining table there is a fresh bowl of steamed rice, a platter of stir fried bitter melon with scrambled egg, and a steaming pot of tea. Smiling broadly, Bo sets the roasted chicken down and admires the laid out table. When he looks up Hua is leaning against the kitchen doorway, watching him.

“I hope you like bitter melon,” she says, “I was surprised to find it.”

A bit alarmed when he hears this, Bo knows that she must have gone out to get the bitter melon. For her to wander the streets of Chinatown alone, and so soon, was a little unsettling. He remembers when he first set foot here and how nervous he was. He couldn’t help but admire her gumption, however. Very quickly he is learning that she is a remarkable woman. And probably would be good at business, he also quickly concludes.

“I do like bitter melon,” Bo Chen replies. “You must have gone out. Where did you get it?”

“At the vegetable market on top of the hill,” Hau said, nodding toward the commercial square nearby. “I think the area is called Little Saigon. I had only a few Chinese Yuan but when I explained in Mandarin that I was out of dollars they were very nice and eager to change my Yuan. Probably they will use them at their ancestral shrines.”

“Yes, I know the market,” Bo said, “they are Vietnamese-Chinese, nice people. And prosperous too.”

Hau remembers the stories her parents used to tell her when she was very young. About being prosperous, then stripped of their possessions and sent to the countryside for agricultural labor. They had warned her of the dangers of being prosperous. So long ago that was. She rarely recalls such lessons. It surprises her a little that Bo elicits such deep memories, and at the same time, a long dormant kind of curiosity.

“Is it important for you to be prosperous, Bo Chen?” Hau asks.

“I suppose so,” Bo replies. “That is why I left China. It’s not everything and I know it will not buy happiness but it’s something.”

They silently exchange looks, and then with their own thoughts, ride the notes of the pipa coming from the stereo. After a few moments Hau suddenly laughs for the first time and says, “And it’s good for business, right, Bo Chen? Sit down. We will have our dinner.”

Except for a small clump of rice and chicken bones, the dinner dishes are bare. Not much had been said as they ate. Most of that time had been spent eating. And with full mouths, it would have been hard to understand each other anyway. Bo was helping with the cleanup until Hau shooed him away.

“I can do this Bo Chen. Go to your couch and rest. It has been a long day and you must be tired. Did your jade customers follow through on their orders?”

“Some of them did,” Bo replies, “all the ones that I notified. I am confident from their reactions that I will do well by the shipment. Are you sure you don’t want my help with the cleanup?” Bo didn’t like such chores before but sharing the task with Hau was different. He wonders how long it will last, how long should it last.

“You go on now, relax and watch your news. I can finish here,” Hau insists.

She notices the difference in Bo from many of the men in China. He doesn’t seem to mind helping in the kitchen. She had heard that Americans, even Chinese Americans, could be like that. Interesting. Before her mind can roam more a field about such things she turns to the task at hand. However, these thoughts about Bo that she puts aside are not new to her.

The TV news is all about the immigration issue. People are complaining about foreigners sneaking into their country. Bo wonders how they would feel if the shoe was on the other foot. Then he smiles and has to admit that, in a smaller and smaller world, and its many issues, many Americans feel that they only have one foot. And, quite naturally, this leaves them crippled. However, this thought is getting to close to politics for Bo Chen. Recalling the graffiti he had seen scrawled on a railroad coal car, “I am a free man. I do not vote,” he will just stick to his own business. And helping Hau.

After the news passes and the crazy reality shows begin, Bo turns the TV off and begins to make his couch, wondering what is taking Hau so long in the kitchen. Then he notices that the kitchen is dark. Under his bedroom door he sees that the light is on. Hau must of gone to bed while he was watching the news. That didn’t seem like her, not saying goodnight. But no big deal. It had been a long day. Dressed down to his underwear, he is just about to switch the end light off when his bedroom door opens. In a very pretty Chinese bed dress, framed by the doorway and the shadowy interior of the bedroom, Hau leans against the door jamb, lifts one hand to her hip and boldly stares at Bo for what seems like a very long time. Then with her face still as blank as the Chinese mask of calm, she almost whispers, “Bo, you don’t have to sleep on the couch, you know.”

Bo Chen admires the dress and the lithe figure of Hau that it reveals. Long gently curved legs end in bare feet with painted toenails. The allure that Bo Chen suddenly feels is not new to him, but the honesty of its pedigree with Hau is unknown. And exciting. Bo stands and slowly joins her, feeling the give of the wooden floorboards with each step.

Intimate talk about their union wanes to a thoughtful silence and the shared pleasure of being spent. So serene is the silence that talk just seems not quite good enough. After a while Hau finds the will to break the silence.

“I enjoy being with you Bo. There are things about you that a woman needs to have in a man. Things that are not all that common.”

“Hau, I could say the same thing about you,” Bo replies. For him there is a kind of relief that these words bring to his soul. “You are still young and I am very happy that you can still like me. I want to do what is right. For me. For you. I admire you and what you have risked to get here. I don’t want to do anything that would hurt that.............it all seems pretty complicated when I think about. You’ve never even mentioned what you went through to get here and I promised myself I wouldn’t ask.”

Hau smiles and looks down to the bed covers for a moment, then looks up at Bo.

‘You didn’t know it but you were helping me before you ever saw me. I knew who you were and I guessed what kind of person you might be. I would probably not have tried such a dangerous stow-a-way if I hadn’t known some things about you.”

“You must of met my exporter, Sun Chan,” Bo says, “he is the only one I know where you come from.”

“Yes, I have known him a long time. He was a good friend of my husband’s. He set up the whole thing because he thought I might have a chance with you.”

Bo Chen smiles, “I’d say that you have got me pretty good. I’m weak as a kitten.”

“Not that way, you,” Hau Ming, says as she slaps him on the shoulder.

“That just happened with a little push from me....sooner rather than later. Sun Chan said that he knew you as a sensible, decent person. Someone who didn’t take advantage of people. He didn’t tell you about me because if something went wrong he didn’t want you to have any knowledge of it. No money was passed or even discussed. He felt that it was something he could do to honor the dead by helping the part of them that lived.”

Bo Chen feels humbled in his own uncomplicated way and simply nods as tears flood the eyes of Hau Ming.

“I’ll never be able to repay you for what you’ve done,” Hau says. “You have shown me that I can care for someone again. I am more alive because of you. And now I need to find work and carve out my existence in this country. Like you once did.”

Bo Chen’s stomach does a flip flop when he hears this. Was she now going away? He doesn’t like the fear that suddenly possesses him and pushes it aside in ways not unlike the way he pushed aside his loneliness.

“Do you want to leave? I suppose there are better opportunities out there somewhere, but you should plan carefully. Of course I will help you if that is what you want.”

“It doesn’t matter what I want. It would be nice to stay with you but you must know that I need to get a hold on my life and that can only come with work.”

Bo Chen does understand. Its not like something that he’s never done. But with him it was all within the system. This is much different. Searching his mind, he takes a deep breath.

“I have a suggestion. My trade in the jade market is really going to take off. And when it does it will require my full attention. There will be no time for the other parts of my business. If I don’t hire help I will have to shut them down and I don’t want to do that. You could work in my shop and take care of that. There is a small kitchen, bed, and bath in the back of the shop that you could use for your own if you want. And I could pay you for you work as well.”

Bo pauses and looks at Hau. Moments pass as Hau thinks about what Bo has just said. She sees the utility in the whole set-up at once. And help beyond any she had ever expected. Plus they could see which of the many ways their relationship might go.

“That could work, blessed be you Bo Chen,” Hau Ming says, “but we must be very careful. I have a Chinese passport tucked away so I can get back to China if I have to. But my real name and who I am must remain secret, else I could be detained and deported. That would be very unpleasant.”

Bo and Hau discuss their plans far into the night. They create a believable story about Hau’s background and determine that, at least to begin with, their true relationship will remain secret. But even if it becomes known such things are not that unusual to begin with. They can handle it. Life will be good.

Month after month, with Bo and Hau working hard and providing good customer service, the tourist shop in Chinatown, now newly named The Jade Emporium, brings in good profits. Because they work close together, careful though they are about their relationship, some people eventually begin to see the little signs of a deeper attachment between them. Signs like a fleeting soft look or a little consideration between employee and employer that is just a bit beyond the normal. But like they had both expected, such recognition is no big deal. People have lives to live and they live them. Who has time to make judgments about people that are not directly involved in their own lives? Live and let live.

Dong Chang, American born and still relatively young, rents the shop space directly across the street from Bo Chen’s Jade Emporium. Not really a part of any neighborhood in attitude, Dong is arrogant and self-centered in the little interaction he has with others. Consequently, his barbeque business is marginal at best. Bo and a few others shop there occasionally and they have learned to just go in, fill the order, pay for it, and get out. Along with his unpleasant manner, Dong Chang is also nosey and quick to deliver up gossip, seeking opinions on its worth. But despite these business problems Dong owns a nice house in Bellevue, drives a new car, and never has much trouble paying his bills. Even when he falls short with his barbeque business, which is most of the time. Ironically, this is due to his past trouble with the law. As a way to get his criminal drug charges dismissed and get started in a lawful business with funds from the government, Dong agreed to become an informant for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement or ICE. Paid monthly for his spying and reporting on Chinatown, Dong brings in a good income as long as he can keep ICE happy and deliver up illegal immigrants. Dong Chang, in simplest terms, is a rat.

On the way back from the Post Office with his box mail, Dong Chang stops on the sidewalk and admires his cover. The rows of barbecued chickens, hanging from hooks under the bright warming bulbs in his shop window, form an eye-catching display. Chickens of teriyaki brown staggered with chickens of soy sauce white, like the dark and light squares of a checkered tablecloth, capture the eye long enough to stir the digestive juices. After unlocking the shop door Dong turns the “Back In A Minute” sign back to “Open” and tosses the mail on the counter beside the register. Immediately his eyes fall on one particular envelope with the United States Seal on it. It must be his monthly check from ICE. Quickly, Dong grabs the envelope, looks to the door to make sure he is alone, and tears open the envelope. Sure enough, there is the check. Dong smiles and considers closing his shop. Who needs to work when they get nice checks like this. That’s when he notices that there is also a note in the envelope. This is rare, usually the nondescript treasury check is all that he receives. As he reads the note a frown comes over his face. It informs him that it has been three months since he has delivered up anyone to ICE. And that this will be his last monthly check if this continues. Dong drops the note on the counter then looks past his barbeque display directly into the glass front of The Jade Emporium across the street. He can clearly see that Hau is helping a couple of customers while Bo Chen is absent. Dong has had his suspicions about those two across the street and he has heard the gossip. Only, when he tries to get any further tidbits from his few customers, they are not forth coming. Dong has been a rat for some time and he has learned the little telltale signs of concealment. He has suspected that there might be something there for him to exploit. And there are no penalties from ICE for being wrong. Having detainees, innocent or guilty, gives both him and ICE relevance. He knows that many of the Chinese immigrants have some things hidden in their closet. A warm body is what he needs now.

The jingle of the front door bell calls Dong away from his schemes as the local vagrant, known simply as Jack, enters his shop for a cheap box lunch of chicken thigh, steamed rice, and a tiny packet of soy sauce. Jack is a peaceable older white American that hangs around Chinatown when he is not at the nearby mission, where he gets most of his meals and a place to sleep when it becomes too cold on the streets. Pretty well known by the shops in Chinatown, he is courteously tolerated, even when he has no real money to spend. Bo Chen and Hau know and treat him with respect when he sometimes comes in to marvel over their jade ware and engage in a little conversation about how it is on the streets. But other than a place to get his box lunch when he can scrap together a little money, Jack has no use for Dong Chang. Dong treats him poorly, always taking his little money as fast as he can, then shooing him out into the street. Today is no different. Dong rudely slaps down the box lunch on the counter, grabs the money and starts shooing him away. However, Jack doesn’t move. He wants a small bag to keep his lunch warm until he can eat it. Now fuming, Dong grabs a plastic sack and rakes the box into it, then shoves it over the counter, pushing it into Jack’s chest. “Now get moving,” Dong says.

“My money not good enough for ya,” Jack grumbles as he takes the bag, and leaves the shop.