Breaking News

Gregory D. Brown

Mark Mooney slid a slice of peppermint chewing gum over his tongue to cover the smell of cigarette smoke on his breath before he opened the driver’s side door of his mom-bought SUV. A gust of wind grabbed tight onto the door and pressed it into a white Mercury parked on top of a faded line in the news station parking lot. It left a dime-sized dent in the smaller car’s urethane-covered steel. Mark looked over his shoulder to make sure no one payed any attention to the audible thwack, caught his reflection in the window, and used his fingers to pull strands of hair back from his face. Blue splotches stained the gaps between clouds as they darkened like the ink from every half-assed story had evaporated with the rain and puddled up in their center, ready to fall to the earth with honest mediocrity.

Mark’s wing-tipped feet carried him across the parking lot in a series of slow-falling clops. Damp air grabbed the mint taste on his tongue and pulled manufactured cold down his throat and deep into his lungs. He eyed a cheap vodka bottle smashed flat against the pavement, shards of plastic splitting at its neck. Construction tape cut him off from the sidewalk, so he paced through a laurel-hedged garden area in front of the news station and walked over its woodchip flowerbed and yellowed rows of giant coneflower as he moved toward the door.

“You’re a brave one,” said a construction worker standing across tape. Another hard-hatted fellow tossed down blown-over bits of tree from the top of a signal tower.

“I like to take risks,” said Mark.

“That’s for sure.”

Mark walked through the door and ducked under a second line of construction tape. He fumbled for his keys and dangled a fob in front of a gray sensor pad. It beeped twice. Mark opened a second set of doors and stepped into the newsroom. Reporters looked over the tops of their waist-high-when-standing cubicle walls, which were drab and (some, mostly former employees, would say appropriately) shaped like swastikas when viewed from above. The meat locker thermostat was contrasted by the visual buzz of soap opera and family-appropriate gameshow programming shot up on dozens of television screens lining the east wall and the aural excitement of police scanners blasting happenings into the assignment desk booth set in the center of the semi-cubicled newsroom. The entire “news” portion of the station was washed in grayscale, save a meteorologist lounge space called the “green room.” Oddly enough, the “green room” was actually a yellow room with a large blue painting centered over a brown couch. Mark assumed the room was repainted after it had been named.

He looked down as he passed Melinda’s office and settled into the chair at his cubicle. Its armrests were split, and bits of foam bled onto Mark’s gray speckled desk. The cubicle was shadow-hued when vacant. He dusted crumbs from his office chair before fingering for the power button on his desktop computer. Two screens glowed blue as the machine powered up. Real-time site visit stats jumped over one another on a third screen hung just above the computer monitors. Mark laid his keys and phone out to the left of his keyboard. Otherwise, the desk was bare. Mark opened his email, searched his name, and found that none of the 359 unread messages crowding his inbox were meant exclusively for him. He then keyed in Melinda’s email address to find a warning telling everyone to avoid the door behind the construction tape.

His hands were sweaty as he typed a list of the day’s assigned stories. A controlled burn had gone out of control in Osage County, two brothers were in court for stabbing their family to death in the suburbs, construction was causing backups in midtown, and two high-ranking deputies lost their jobs for sharing sheriff’s office secrets on Facebook. Mark deleted a swath of emails from viewers seeking their lost uncles, daughters, and dogs.

“And nobody’s able to help you.”

“What was that?” asked Kathryne from the next cubicle.

“Oh, nothing,” said Mark. “I was just reading through the viewer emails.”

“A psychic said she knew where the blind horse is.”

“Thank God. Spirit’s coming home.”

Mark opened a file cabinet and produced a wide-ruled notebook with a Tulsa-area semi-professional soccer team logo on the cover. He flipped through the notebook, found an empty page, and wrote down reporter assignments and the week’s online trending content to read aloud at the meeting. None of the other digital producers handwrote notes before the meeting, but the visible lists left Mark feeling like he did more than dick around on social media for a living and gave him a wall to hide behind when he had to speak in front of his coworkers. He opened the station’s social media pages and started reading through posts. A woman asked if they would investigate her apartment complex’s mold problem. She said her son was sick from the stuff and the landlord refused to look into it. Mark typed “thanks for sharing” and sent the message to the trash folder. He saw a manager wheel a whiteboard into the conference room and walked to the meeting.

Mark sat in the first pale chair near the room’s pressed plywood door. He pulled out his phone and brushed through web articles while producers went over the particulars of the next ninety minutes of newscast. Occasionally, he would sit up and look at Melinda as she talked to let her know she was worth his time and attention and that he deserved a raise. He was reading an article on Camus when he realized she was, in fact, talking to him.

“How can we tie the Supreme Court rulings to the web?” she asked.

“I planned on posting a localized story on the rulings, relating them to the recent bills pushed through state legislature,” Mark said. He looked up from his phone and wished he could force blood back from his cheeks and ears. “It’ll be up by six”

“That works. We really need to tie in the local impact,” Melinda said. “Viewers are turning away when they see big national stories that they can find anywhere online.”

Mark felt guilty for letting himself grow comfortable in the meetings, though he was satisfied with his manufactured, on-the-spot response. Regardless, he was embarrassed by the way he had been caught off-guard. He pocketed his phone and stared at the notepad. One of the evening anchors, Roger, rushed in the room and sat cross-legged on the geometrically-textured, commercial carpet near the door. He leaned onto the wall just beneath a poster hung to remind the staff of the simple and albeit obvious steps necessary for a better, faster, and more entertaining newscast. A producer was talking about the way an area oil executive had burned to death in his car only a day after he was charged with embezzlement. The man drove into a bridge at 78 miles per hour and his fuel tank exploded, charring his suit-bought-by-misappropriation and leaving his newly-bastardized daughter with at least one less birthday present the next spring.

“A bit ironic isn’t it?” Roger asked.

“I’ve been waiting for you to show up and make a joke about the whole ordeal.”

“It’s not too soon?”

“In this business, it’s never too soon.”

“Well, what can I say? The oil industry is exploding in this state.”

The giggles grew into an Om. Mark looked up from his notepad and flashed Roger a smile. Melinda, covered her mouth, cleared her throat, and read numbers from a chart showcasing the station’s recent rating progress. The nightly reporters filed in, each giving up a joke or a compliment as an offering to the management staff and midday workers already sitting in the conference room. One said something about Mark’s shoes. Another sat next to him as if it didn’t make them both uncomfortable. Her oil-based, spiced rose scent was just strong enough to make Mark constantly conscious of it. The reporters started in on their pitches. One of them was assigned a police fraud case in a rural county about an hour and a half’s driving time from the station.

“Well, after last night, I can handle whatever Oklahoma has to throw at me,” he said

“What happened?” asked Jennah, the night-side assignment desk warden.

“You didn’t hear about the racist rabbi?”

“A racist rabbi? Was this when that 10-year-old crashed his dirt-bike into a pick-up?”

“Yes. I guess the pick-up driver was also black, and the paramedic who took the kid into the back of the Life Flight copter was black too. So, this rabbi comes up to me and said, ‘You know, this is really something. I don’t mean to be crass, but we don’t see a whole lot of you out here.’”

The room bounced along another laugh.

“A rabbi in rural Oklahoma said African Americans were rare?”

The crime reporter next to Mark quieted the group with a glare. She needed to finish her pitches and head out to a three p.m. interview with a rape victim. Mark took at least ten minutes to return to olfactory stasis after she was gone.

Frozen yogurt was set out on the assignment desk after the meeting. Mark ignored the police scanners’ roar as he dug a small carton of it from the bottom of a cardboard box and walked to his desk. He pulled a plastic fork from his file cabinet and ate the yogurt while he typed out the evening’s social media plan. Kathryne was crying.

“The court released the transcripts from the Bixby brothers’ trial,” she said

“Is it rough?” Mark asked.

“They stabbed their mom like 87 times and cut off their brother’s head with an axe.”

“Any reason why?”

“They wanted to start some kind of religious revolution.”

Mark finished his frozen yogurt and tossed the cup into the trashcan beneath his desk.

“I’ve only cried three times over work in the last 13 years,” Kathryne said. “When the drive-in theater burned down, I cried. When someone shot at grade school kids on the east coast, I cried. Now, reading about teenagers slaughtering their family for their imaginary friend is making me cry.”

“Yeah, that’s pretty rough,” Mark said.

He started scrolling through Facebook again.

“I think I’m going to go home early to drink wine and see the nephew,” Kathryne said. She wiped black stripes across her face from the corners of her eyes and looked a bit like the first stroke of a 1951 Pollock. She pulled an un-popped bag of gluten-free popcorn from under her desk and walked into the break room. Mark checked the station’s Facebook page again.

Someone had sent in a message about their missing teen turned up dead. Mark read through the description and took a second to look at the picture. The kid’s white arms hung from massive holes in a black, off-brand t-shirt. A sweat-stained Texas Rangers cap kept the boy’s curly red hair tame (or at least domesticated) for the picture that would memorialize him to Mark Mooney. The boy had gone missing from a local rock festival earlier that summer. He was autistic and had trouble socializing, at least, according to the post. He was found drowned in a 1985 red Ford pickup truck alone. At least the Bixby family died in the comfort of their own home, surrounded by those that loved them the most. This kid just had b-list rock and roll and a tank full of diesel.

“Maybe you should have developed a healthy relationship with your kid,” Mark muttered as he deleted the message.

Kathryne came back to her desk and Mark started telling her about a dream he’d had the night before while she ate her bag of popcorn. Someone noted the popcorn’s smell from across the newsroom as if the salt and butter scent didn’t rise from the desks of dieting television bodies every other day. Kathryne laughed at Mark’s dream and told him she was going to send him the details of the Bixby killings so he could transcribe them and she could go home. Mark said that was fine as if a dissenting opinion would have spared him from reading more courtroom notes. She sent him the email, left her jacket in a wad on the top of her chair, and left the station.

Mark opened the email. The brothers had wanted to stop their family from shooting their neighbors and bringing the kingdom of heaven to the Tulsa suburbs. Mark was glad they’d done it. The last thing Oklahoma needed was another spirit-filled shooting. Mark was also satisfied with the brothers’ swift arrest after he read that the younger of the two wanted to become a god himself. Oklahoma didn’t have a whole lot of room for new gods. The one they had was causing controversy with a statue at the state capitol, and legislators didn’t seem to like the idea of housing any others in the Sooner State. The boys had slit their sister’s throat. She ran outside afterward, and it probably saved her life. Mark was glad she survived, but he couldn’t imagine her future being too incredibly bright. The kids didn’t have any friends to begin with, and Mark had never tried to strike up conversation with a person who had scars on their neck.

Mark found ways to omit some of the more violent bits of the story from his article as he worked his way through the document, sliding his eyes through each noted stab and running a finger along every typed-up serration. Once the story was posted on the station’s website, comments started pouring in from people demanding the brothers be hung. Mark didn’t think there was grace enough to deny the mob their request. One commenter asked if any of the others had seen her missing horse. It was blind.

“If there isn’t mercy for these boys and their families, how can you expect someone to grant you the grace to find a horse?” Mark typed. He erased the response and substituted it with, “Thanks for sharing.”

Mark stood up and walked over to one of the late show directors who smelled like tobacco every time he popped in for a newscast.

“Hey, do you smoke?” he asked.

“Yeah, why?”

“Can I bum a cigarette?”

“Sure.” He shuffled a hand into his shirt pocket and produced a Marlboro.

“Thanks. I’m out, but today calls for nicotine. Kids killing families, Jesus killing neighbors, and people asking dumb questions on Facebook.”

“I heard that,” the director laughed.

Mark slipped outside and smoked his cigarette alone. He watched the top of the sun wink as it fell behind the skyline. A flock of birds filled a row of dogwood trees. They called together to mock Mark as they shit on his car. He finished his cigarette while walking to the nearby liquor store to buy a bottle of cheap bourbon. His shoe grabbed the glowing butt and pulled it out against the sidewalk without really affecting his pace. He opened the fingerprinted glass door to the liquor store. The woman leaning hard on the cash register was wearing a blue sweatshirt with a cartoon bird on the front. The print was chipped like she had dried the shirt without taking time to read the tag. Mark couldn’t decide if the woman was in her fifties or if she too had been dried too hot either in a tanning bed or at the back end of decades of Virginia Slims. Her lips were chapped and seemed to crack open when she asked him to show her his driver’s license before he paid for the bourbon. He couldn’t help but stare into the little canyons and wonder how they weren’t red with blood.

When Mark got to the parking lot, the sky was dark. He threw the bottle in the backseat of the shit-covered SUV. He hid it beneath the passenger’s seat and found a half-smoked pack of cigarettes there. His phone buzzed in his pocket. Evelyn asked if he wanted to come over to her house after work and have a drink with “some people.” He didn’t reply.

Mark drug his feet against the carpet when he wandered back to his desk. He put in earphones and let the two late shows fly by without incident, quickly hammering out the reporters’ stories with little detail or care. He quit checking the social media page, left any cries for help to the morning shift.

As soon as the final show’s credits started rolling across a monitor at his desk, Mark slipped out the door unnoticed. He neglected to say goodbye to Jennah at the assignment desk and ignored the security guard’s well wishes as he walked to his car. Two women were walking across the station’s parking lot from one of the motels across the street. Even in the dark, the older woman’s thick skin glowed brown. She haphazardly held a baby. The younger woman waddled in her sweatpants as they crept down legs. She called to Mark.

“Can you give us a ride? We live just down the street.”

It started sprinkling in the parking lot.

“Sorry, I’ve got somewhere to be.”

“What’s your problem, man? It’s how we look isn’t it.”

The car started. Mark drove away. It had nothing to do with how she looked. He had somewhere to be. The younger woman’s pants sagged lower down her legs.

Mark was the last of his friends to arrive at Evelyn’s house. She lived in an older house in midtown. It was just on the edge of the cool part of town and the old part of town. Mark lived around the corner in a newer apartment complex. He parked his car along the street and hobbled up to the door. It had stopped sprinkling. He knocked. Josiah answered the door. Patrick and Anne were already inside. Mark said hello and walked over to the kitchen sink to open his bottle of bourbon. He poured himself a glass of the stuff and drank it down without taking a breath. He poured another and wandered into the hazy living room where Patrick and Evelyn were smoking weed through a marbled stone pipe. He started in on the second glass and began telling his friends the not-safe-for-news details of the Bixby brothers’ murders. Patrick decided religion was likely the cause. Mark couldn’t find it in himself to argue with that. Josiah fell asleep on the couch. Mark finished the bourbon in his glass and walked to the fridge and took a beer without asking. Eventually, Evelyn and Patrick decided they wanted to go smoke a cigarette, so Mark picked up his beer and followed them outside. His shoulders tilted under the weight of the bourbon he’d already drunk and he stumbled across the porch.

Patrick asked about work as if Mark had at any point talked about anything else.

“They’re all pretty fucking hopeless,” Mark answered. “All these helpless sadsacks send us the same, mundane, bullshit questions. It’s like, ‘Sorry, I can’t help you find your kid. Thanks for sharing.’”

“Yeah, that would get on my nerves,” Patrick said.

“You don’t understand, man. At the shoe store, people were asking you to fulfill a specific task. You put shoes on people’s feet, they pay for them, and they walk out. At the news, I’m just supposed to find information and report it, but people insist that we fix all Tulsa-area atrocities, most of which they caused themselves by moving into a mold-riddled apartment or buying drugs from strangers. The problems they didn’t themselves cause are so fundamentally rooted in the human condition that there’s no hope anyhow.”

Patrick dragged hard on a cigarette and Mark sucked on his beer.

“That’s the thing, man,” Mark said. “We can’t fix anything. God can’t fix anything. Those kids still stabbed their parents. Some moron’s blind horse went missing. It happens.”

It started sprinkling again, and Anne came outside with the rest of the group. She asked Mark for a cigarette, and they all stood on the porch and watched the drops darken the sidewalk. Mark felt heavy. A car drove by. He wanted to jump in front of it. He finished his beer instead. It started raining harder. Anne and Patrick woke up Josiah and went home. Another car drove by with its lights out. Lightning cracked behind it as it passed.

“It’d be nice if someone cared like these people want,” Mark said.

“I think people do care, just not you heartless bastards at the news,” Evelyn replied.

“I mean, sure, but the only people that care are the ones that you expect to care. What’s the use of caring at that point?”

“I think you’re drunk.”

“But do you care?”

“Of course I care.”

Mark leaned over and tried to kiss her. She turned and his lips smashed against the soft part of her cheek.

“Mark, you’re drunk. I’m calling someone to get you.”

“Whatever, it doesn’t matter. I’m going home.”

Evelyn ran inside the house to get her phone. Mark smashed his beer bottle on the porch. He left orange-brown glass on the step and threw the remaining half of the bottle into the street. He got in his SUV and slid his remaining cigarettes back under the seat before Evelyn made it back outside. The rain crashed hard against his windshield. He navigated the two turns it took to make it to this apartment complex as fast as he could. Mark parked in the spot nearest his door and pulled himself up the stairs and into his bedroom. His clothes fell off his body like a rack of ribs held too close to hell for just the right amount of time. The bed was cold against his bare skin.

Mark set an alarm for noon and closed his eyes. He rolled around beneath the chilled sheets. He slid along the line of sleep until he heard a growing moan. Mark woke up when he realized it was his own moaning. He walked into his bathroom and fished through pill bottles for Xanax he had been prescribed in high school. He couldn’t find any. He fell back on the bed and shook himself to sleep.

Mark woke again at 9 in the morning, sat up, and put on shorts, a t-shirt, a black cap, and his running shoes. Crisp air stabbed at his face when he started to jog the sidewalk. Oxygen poked holes in his tarred lungs and the flames from every cigarette he’d smoked in the past month relit on the gray-pink tissue in his chest. Mark started thinking about the Bixby brothers. He imagined their knives breaking their mother’s flesh. He thought about the entry, exit, blood. The boys demanded their mother’s parental power over and over and over again when they stabbed her in Mark’s head.

A man and his two kids sat on the side of the concrete path, and Mark did his best to look away from their sloppy cardboard sign. Eventually, he couldn’t help himself, and Mark read what he assumed were the father’s words in the children’s handwriting. “Help, we’re sick. Need change.” Mark didn’t have change on him, anyhow, so all he saved the trio was a pitiful apology when he passed them. It’s not like any number of coins could save them. There was not enough grace to keep kids from killing their parents or their parents from killing their neighbors or their neighbors from killing their kids’ dreams or their kids’ dreams from killing the harsh realities they would someday have to face. There was not enough grace to keep Mark from wishing he were dead, nor was there enough mercy to let him forgive himself, Evelyn, or any number of kids, murderous or Sara-McLaughlin-commercial-ready or otherwise.

He threw up on the side of the trail. Mark walked back to his apartment. He took a shower and brushed his teeth. He typically ate lunch with Evelyn before heading back to work, but he didn’t feel up to it, and the previous night’s events didn’t seem to yield an ideal setting for lunch dates. He got dressed and ate a quesadilla at a nearby Taco Bell before he scuttled off to work. He fished out the nearly-empty pack of cigarettes from beneath the passenger seat in his car and smoked his way to the station.

The newsroom was empty when he rolled in. The managers were gone to a conference, and a few of the producers were out on their late-summer vacations. No one was at the assignment desk, so Mark sat there and listened to scanners. People beat their wives and drove too fast on highways. They got too drunk and dealt drugs and touched their kids. The phone rang. Mark answered. A thick voice on the other end of the line asked him to take a picture off the news site. The man had driven his car into a house and flipped off the cameraman. Mark told him he’d pass the information along. He sat silent after the guy hung up on him. He walked to the vending machine and bought a bag of chips and a soda. He went back to the desk and listened to the scanners again. Someone shot at strangers through their car door, but no one actually ended up bleeding over it, so Mark kept it to himself.

The phone rang again. Mark answered it after just one ring. A man on the other end of the line went on about his dying.

“... and I went to all the churches in town. You know, the big ones. The First Baptist Church, the Presbyterians, all of ‘em. And do you know what they told me? They said they only give out food. Now, I’ve worked every day of my damn life, and I can’t afford these prescriptions. I had two strokes, and they just want me to lay down and die?”

“I can see why that would be stressful,” Mark said.

“Well, what am I supposed to do? I can’t afford the medication, but the doctor already called for the prescription. These churches are supposed to do the work of God, but they couldn’t care less about people like me.”

“I’ll pass your story along and see if any producers want to pick it up,” Mark said, hanging up the phone as the hands and feet of God had before. He turned toward the scanners and heard something about a wildfire. He called the responding fire department, but no one answered. He sent out an email telling the fill-in producers about the blaze, pushed the old man from his head, and waited for Jennah to come relieve him at the desk.

When Jennah did come, it was dark out. Mark headed home for his break. The cool air pecked at his cheeks. He walked into his car and pulled out a cigarette. He lit its tip and started toward his apartment for a sandwich. The whole way back, Mark kept his music louder than it should have been to keep him from thinking about much of anything. He imagined two teens stabbing their parents to death, their knives slicing through the cheeks they kissed when they were toddlers, the eyes that had made sure to care for them looking through them sightlessly. And there would be blood, like, the whole floor would be stained red, and it would stink like hell in a couple days. The brothers’ hands would have little nicks and cuts along their fingers where their hands slipped down on the knives as they collided with the solid floor beneath their parents butchered bodies. Mark thought of their church, just days after the murders, preaching love and acceptance, and, of course, refusing to help a sick old man. When God chose to kill people, it was His will, though the congregation would sometimes much rather do it themselves. Mark decided to stop at a gas station and get a pack of watered-down Oklahoma beer for after work.

He settled on a suggestively named joint just north of his apartment complex. Mark walked into the Kum and Go, and overheard the clerk telling an old, tattooed man in a blue and gray pearl snap that her father had patented an engine for Tesla and more recently contracted some sort of heart disease that left one of his feet dangling in a six-foot hole in the ground. Mark wondered which was more important (the engine or the heart disease) as he grabbed a pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon. He took maybe two steps toward the cash register before he realized he had to pee. He set the beer on counter and walked into the bathroom. He finished his business and went back to the counter to pay for his beer. A white man in a black hoodie walked into the convenience store. He put a gun in Mark’s face. Mark looked deep down the barrel, imagined the lead waiting in the chamber, and almost smiled.

“Get the fuck on the floor.”

Mark politely kneeled down next to the counter. The guy grabbed his cash and was out the door in less than a minute, hardly a crime, really. Mark looked at the clerk crying behind the register, picked up his case of beer, and wondered what kind of jokes he could make about the robbery when he got back to work as he walked out the door.

|

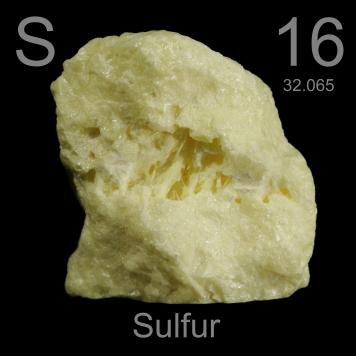

Smelling Sulphur

on Nine One One

Janet Kuypers

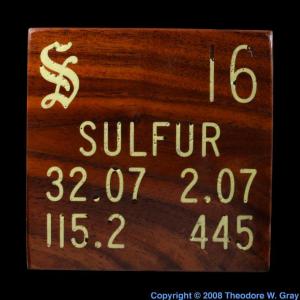

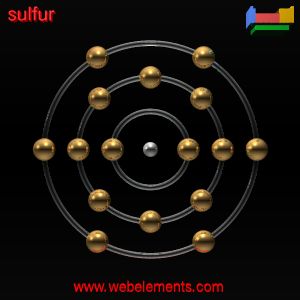

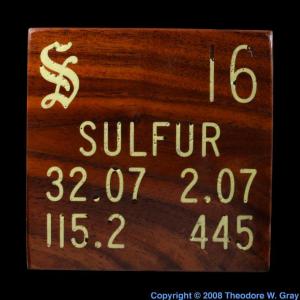

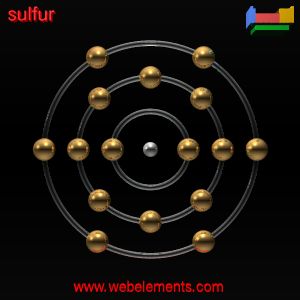

bonus poem from the “Periodic Table of Poetry” series (#016 S)

9/11/13

I’m a journalist.

I can remember

the sounds of the newsroom

as I finished my articles

at one of the computers.

I can still hear

the sounds of the bustling,

of the rushing toward a deadline.

The shuffling of papers

was a constant presence

when you worked.

Hearing that low hum,

that din of action and activity

is almost comforting

to types like us.

It was the base beat

to the symphony of our lives.

So, when you hear the words

nine one one,

you think of the number to dial

when you hear of more gun violence

on these Chicago streets.

You smell the Sulfur

in the gunpowder,

another sense

that accentuates the center

of the world around us...

But on a beautifully

sunny day like today,

you come into the newsroom

in the early morning,

and the sound of action

has yet to truly penetrate the ears

of these reporters,

with a styrofoam coffee cup in one hand,

crumpled pages of edited copy in the other.

But on this sunny morning,

the din was different,

much more cacophonous,

much more rushed,

while still so hushed.

I made my way

to one of the TV sets

along the main wall,

all were on different channels

showing different bits of news,

though all suddenly seemed the same.

It looked like the newsroom

was watching a movie

as smoke poured

from one of the Twin Towers.

I tried to make out the voices

from one of the TV sets

when I witnessed a plane —

right before my eyes —

fly into the other Tower.

I stood for a moment,

transfixed like some

horror movie addict,

before I thought of our contacts

scattered along the east coast.

I pulled out my cell phone

and speed dialed Mark in New York,

he had a meeting scheduled

in the Twin Towers that morning,

but the phone was jammed,

so I dialed up Don

who was in town there this week,

but all was lost

to computer-simulated voices,

forcing me to leave messages

and scramble from afar.

As pathetic as we were,

we stared at TVs

as most forms of communication

were cut off for us.

Was this an attack on New York,

we struggled to discover

until less than forty minutes later

we saw the two-second long film

replayed repeatedly

from a D.C. security camera

that caught a collision course

crashing of a plane

through the outer rings

of the Pentagon.

Well.

Now the story has changed.

Try to get through

to Dan in D.C.,

was he in the Pentagon today.

The phones still cut me off.

So we scrambled for any data,

looking for a Chicago connection:

the Sears Tower,

the John Hancock building,

these are national icons

that may be under attack...

But before we could gain our bearings,

only twenty-five minutes passed

before a plane crashed

into the ground

near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Shanksville, I thought,

I know someone there,

I searched, and found

Anna’s number,

but who was I kidding.

Those lines were cut off too.

#

It’s a strange feeling,

being a reporter

and not being able

to contact a single person.

Being detached from any lead,

coupled with a sinking feeling,

wondering if any

of the people you know

are physically hurt,

or even alive.

As a journalist,

you really feel hopeless,

like your hands are tied

behind your back.

We give the news.

We’re not supposed

to feel so stranded.

#

An hour after

the Pentagon was attacked,

the Sears Tower was evacuated.

This wasn’t my beat;

I had no contacts, no one

to help me through this disaster,

so I waited there

in case others

needed any assistance.

I sat back for a moment,

left there to wait,

thinking about

Mark and Don in New York,

Dan in D.C.,

even poor Anna —

I’m sure she’s not hurt,

but they’re now cut off to me.

As I said,

all I could do

was wait.

Clear your head of the people,

I could hear myself

say to myself.

You’re a reporter,

just break down the details

of what you see

instead of thinking of this

as another one of your

human interest articles...

The jet fuel,

the drywall,

all that paper

in those offices,

those people,

trapped,

they’re all

hydrogen, carbon, oxygen.

But wait a minute,

in Chicago I think

of the Sulfur smell

when it comes to gunfire.

But jet fuel is Sulfur-laden,

that burning drywall

emits Sulfur gas,

Sulfur’s even the third most common

mineral in the human body.

I mean,

I’m a newspaper reporter.

I know that Sulfur-based compounds

are used in pulp

and paper industries.

#

Yeah, I’m a newspaper reporter.

Just take a breath

and turn your head to the stats.

To clear my head

of the humanity,

the thought of so much Sulfur

being so much a part

of so many details in our lives,

made me think

of the destruction

that Sulfur was so much

a part of today.

I know I stayed here

to give a helping hand,

but with all that Sulfur

on my mind,

suddenly

all I could smell

was the burning,

and I couldn’t stop coughing

while I tried to catch my breath.

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her Periodic Table bonus poem Smelling Sulfur on 9/11 live 9/11/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (C)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her Periodic Table bonus poem Smelling Sulfur on 9/11 live 9/11/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (S)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Periodic Table poem Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One in her Opening Act feature (with music by the HA!Man of South Africa, with “Alex”), live in Chicago 10/4/13 (C)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Periodic Table poem Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One in her Opening Act feature (with music by the HA!Man of South Africa, with “Alex”), live in Chicago 10/4/13 (C)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Periodic Table poem Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One in her Opening Act feature (with music by the HA!Man of South Africa, with “Alex”), live in Chicago 10/4/13 (S)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this Periodic Table poem Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One in her Opening Act feature (with music by the HA!Man of South Africa, with “Alex”), live in Chicago 10/4/13 (S)

|

Watch YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading eleven Periodic Table poems in her show “Opening Act” with music from the HA!Man of South Africa in Chicago (filmed with the Canon video camera), including this poem

|

Watch YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading 9 Periodic Table poems in her show “Opening Act” with music from the HA!Man of South Africa in Chicago (filmed with the Sony video camera), including this poem

|

Download this poem in the free PDF file

Opening Act chapbook,

w/ Periodic Table of Poetry poems.

|

See YouTube video on 9/11/16 of Janet Kuypers saying her poem Ever Get It Back in conversation, then reading her 2 poems September 11, 2001 and Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (video filmed from the Canon Power Shot camera).

|

See YouTube video on 9/11/16 of Janet Kuypers saying her poem Ever Get It Back in conversation, then reading her 2 poems September 11, 2001 and Smelling Sulfur on Nine One One at the Austin open mic Kick Butt Poetry (video filmed from a Sony camera).

|

Freedom

Marlon Jackson

I’m suffering like a slave working and working

without anything to show for it, sneezing and

coughing.

And at home most times I can’t sleep, I just

can’t and I really don’t know why.

Yet when I do, it lasts just a few hours without

my body feeling fully rejuvenated and 100% charged

like a battery and sometimes immediately I slow down.

I run out of energy un-realizing what’s at stake and my

life is too costly.

But I still have it in me...that will break through.

I yet I still am trudging within the dark seeing my

opportunity and I’m being tactful and persistent.

There it goes not too far from me...that light I see it

and I don’t need to run to it.

It’s coming to me...because I really need it there it goes...

My freedom.

|

A Fool’s Dream

Renuka Raghavan

Week after week, the man in the navy suit sits front row. He smiles when I appear on stage. He appreciates every grand jeté I perform. At the end, his applause resonates loudest, throughout the hall. You’ve watched my every performance this season, I say. He nods, shy eyes looking all around before focusing on me. An older gentleman, but handsome nevertheless. So, are you a die-hard ballet fan or do you want to ask me out? Neither, he says. My daughter dances, but I can’t watch her. I prefer to watch you and dream of what she could’ve been.

|

Renuka Raghavan Bio

Renuka Raghavan is the woman in front of you in line at the store who just piled on a month’s worth of groceries onto the conveyor belt only to realize she left her wallet in the car. Next time, say hi, she’d love to meet you! She writes and lives in Massachusetts. Visit her at http://www.renukaraghavan.com onlne.

|

Of All the Things Forgotten

Renuka Raghavan

I watched in silence as he rocked slowly back and forth like the mini pendulum I kept on my desk at work. These weekly visits were hit or miss, at best. Today, though, had been a good day. We had lunch. We played chess. Now we sat in silence on the porch, watching raindrops create rippled patterns on the pond’s surface.

“You know, Beth, I do appreciate all the time you spend with me. I don’t say it often enough.”

Following a long pause, I said, “You don’t have to thank me, Daddy. Visiting you is the highlight of my week.”

He held my hand in his, “My sweet, sweet Beth.”

I wanted to reach over and shake him. How he’d forgotten so many things.

I wanted to remind him that I hated eating soup for lunch just like he once did. That a rook couldn’t move diagonally. He should know; he’s the one who taught me!

Most of all, that I was Emily.

The surface of the pond was still, diseased with wrinkles.

I squeezed his hand, not bothering to swipe the tear that fell.

|

Renuka Raghavan Bio

Renuka Raghavan is the woman in front of you in line at the store who just piled on a month’s worth of groceries onto the conveyor belt only to realize she left her wallet in the car. Next time, say hi, she’d love to meet you! She writes and lives in Massachusetts. Visit her at http://www.renukaraghavan.com onlne.

|

The Blind Date

Mikala Bice

I was sitting there thinking why in the hell did I agree to this blind date. My friend set me up with someone who they thought would be my perfect match. My friend must secretly really hate me because this guy was anything but my perfect match.

At first, the date started off a little bit rocky because the guy decided to show up thirty minutes late, and even admitted to me that he did it on purpose, too. I could tell from that moment on how the was going to go, but I was so curious to see how bad it would get.

The restaurant was nice, though. The wait wasn’t all that bad because of the great service and activities that I could do if I wanted. They gave me a few crossword puzzles do after I asked for them, so I was entertained the whole time. The guy was lucky that he showed up when he did because I was ready to order, eat, and leave. I don’t like to be stood up, and I won’t tolerate it either.

A few minutes after the guy sat down we were asked if we were ready to order yet. The guy was definitely ready to order because he didn’t even look at the menu before he ordered. He ordered the steak with a side of mashed potatoes, green beans, small salad, and buttered rolls with a big pitcher of beer. When the server asked me what I wanted to order, my date opened his big mouth and ordered me a salad with no dressing with a glass of water. I was too shocked to even object to the order before the server walked away. I stared at the guy with unbelieving eyes, but all he did was complain about how bored he was in the nice restaurant.

He finally looked at me, and asked if I had a mint before he ate his dinner. I was wondering what was wrong with this guy after that. This was the worst date that I have ever had. I started to really hate my friend right then.

I told him that I didn’t have a mint, and that I didn’t appreciate him ordering for me. He told me that I should appreciate that he did order for me because I needed to lose a few pounds. That for me was the last straw. I was leaving because I didn’t deserve this at all. The way he was treating me was uncalled for. I told him before I left that he could pay for the check because he ordered it all anyway. I didn’t stick around for him to yell or do something stupid, like slap me. That’s the last time I let a friend set me up on a blind date.

|

What Remains

Amy Soscia

Construction noise from her new neighbor’s yard woke Phyllis again.

“What’s going on over there?”

Phyllis knotted her robe, then slipped out into the moonlight. She wriggled through overgrown hedges and walked toward the trees whose canopies had obscured her view. A crew of men worked like drones in a hive. Yet it was the two limestone sarcophagi, jutting out of the earth, that caught her attention.

“May I help you?”

Phyllis jumped.

“The machines, I couldn’t sleep,” she stammered, pulling the edges of her robe together, noticing how impeccably dressed Luigi Bandino was, despite the early hour.

“I apologize for the noise. My workers have limited daytime availability.”

“What are you planning to do with those?” Phyllis pointed.

“A Halloween decorating contest for the neighborhood kids.”

“With a last name like yours, I imagined you’d put the dead bodies in them. You know, the ones that get whacked,” Phyllis giggled nervously.

“You watch too much television. That’s the last place anyone would hide dead bodies. Too obvious,” he laughed.

“Silly me.” Phyllis turned, missing Bandino’s nod to the worker.

“Such an imagination,” Bandino said, stepping away before the shovel slammed against Phyllis’ skull.

|

Social Experiments, Or How I Prove Nice Guys Are Assholes

James Raisanen

I arrived at the restaurant about twenty minutes early. I sat in my car, just listening to music while I waited for the agreed upon time. I must have dozed off because the next thing I knew, it was almost five minutes after. I rushed out of the car and into the place, and the waitress told me that my date had already been seated. She showed me to his table and I thanked her.

Getting into the chair, I nearly fell over it. I could have died, figuratively. The expression on his face embarrassed me even more, and I could feel heat rush to my face.

“My name is Club Magnum,” he introduced himself.

I laughed out loud and hard. He looked so angry that I felt bad and stopped laughing with a little difficulty. If I sprayed him with saliva from the sudden burst of laughter, he didn’t say anything about it.

He shook his head and tried again. “I’m... Matthew... Callon.” He picked up the two menus and handed me mine. “What’s your name?”

“Ginny Walters,” I said. “Sorry I’m late. I swear I got here super early to avoid just that.”

“I forgive you, Ginny.”

The waitress walked up to the table. “Do you know what you want?”

“Yes. I’ll have a lobster dinner, a side of fries, and a Coke; and she’ll have a side salad, no croutons, no dressing, and a glass of ice water.”

The waitress finished writing the order down, then reached out to take the menus. She walked away with a smile and not another word.

“So, what do you do for a living?” he asked, as if nothing had just happened.

“Um, okay. I’m an assistant manager at Always 13.”

“Oh, that’s interesting. I’m a systems analyst for BTI. I set up the computer systems for the entire building, and I make sure that everybody’s programs are working smooth...”

I cut him off. “Are we really not going to talk about what happened a couple minutes ago?”

“What do you mean, Ginny?”

“You ordered for me. You didn’t even ask about my job.”

“Oh. Sorry.”

“You’re sorry?” I asked incredulously. It was then that the server brought the salad and drinks. She assured us that our food would be out soon, then walked away again.

“Yeah, I’m sorry. So what’s your job about?”

“Always 13 is a clothing store for pre-teen girls. So many of these girls are annoying, I can’t stand it sometimes.”

“So what are your hobbies?”

“Uh... I don’t know. Sitting around and watching movies on WebMovie. Sometimes I go to the park, or clean my apartment. What about you?”

“Oh, my god. I love WebMovie! I don’t think I could live without it. But the park? Going outside? Ew.” He was about to speak again when the server set a stand down so she could more easily dole out the food.

“How is everything?”

“Fine.”

“Fine.”

She smiled and nodded, then packed up the stand and tray and walked away.

“So what...”

“No talking,” he said.

My face scrunched when he said that. I relaxed and ate a few bites of my salad before testing him again. “Do you really...”

“I said no talking while I’m eating.”

The instinct I had first saw his profile on seeyou.com had been proven correct, and I couldn’t be happier.

We sat in silence while we ate our food. Every so often, the waitress would come back and ask how things were, or if we needed refills.

“You can pay for the tip,” said Matthew, after we were done and the bill had been brought to the table. “It should be about five dollars.”

I left the money on the table, stood, and walked toward the doors. Matthew was close behind, but when he stopped to pay, I kept going. I decided to wait for him just outside.

“Can I get your number?” he asked after coming outside.

I wrote it down on his hand, then kissed him on the lips. “Why don’t you give me a call sometime this week?” I walked back to my car without giving him time to answer. By the time I got back to my car, I was already considering new experiments to push his underlying nature to the limit.

|

The second bed

Benjamin Uhlich

Carl opened the door to the hotel room he and his wife Cheryl stayed in. “Two beds?” he said, “I’ll call the front desk and sort this out, sweetheart.” The telephone sat between the two beds on a small table. Carl walked between the beds. “What’s the number to the desk?”

“Don’t worry about it, Carl, we can sleep in separate beds for one night,” Cheryl said. She entered the room and set her duffle bag on the bed closest to the door.

“I guess It’s a very nice room despite the mix-up.” There was a private patio through the sliding glass door on the far side of the room. On the wall opposite the beds were a television set and a minibar. “I’m going to go smoke outside, honey. If you’re hungry, you can order room service.”

Carl stepped outside and lit up a cigarette breathing the smoke in slowly, tasting tobacco and addiction. “Nasty habit, I should really quit for Cheryl, she hates these things,” he said. Carl took one last drag of his cigarette and put it out, tossing the butt followed by the rest of the pack over the patio railing. He turned around and went back into the room.

A metal cart sat by the front door. Cheryl sat on the edge of her bed with a plate in her lap eating chicken. She smacked her lips together as she ate, the noise echoed in the room. “There’s nothing like hotel food,” she says with chicken in her mouth.

“Wonderful, I’m starving.” Carl walked to the cart and removed the lid from the tray. “Darling, there’s nothing left.”

“That’s because I ordered enough for myself, Carl.” She turned on the television and removed all of her attention from her husband.

“We should probably try to head out soon, so we aren’t late for the play, I’ll just get something to eat after.”

Cheryl snapped her head towards Carl with a nasty scowl on her face. “I’m enjoying this program.” Her gaze regains focus on the television. “You can just go without me, I’ll stay here.”

“What are you saying?”

“I’m saying I’m tired and I want to stay here, Carl, not everything can be romantic.”

“Romantic? Nothing is romantic anymore. I set up this special night at your favorite hotel. I even got us tickets for your favorite play, and apparently you want to sleep in separate beds, fend for ourselves for dinner, and skip the play.” Carl’s face turned bright red and heated up as if the fire in his heart was showing in his face. “All you do is look out for yourself.”

“I’ve been looking out for you, and our son for the last twenty-five years.” Cheryl turned off the TV. “But now Joe has moved out of our house and I’m just done putting myself last.”

“What do you mean?” he asked, as tears welled up in his eyes.

“I want to pursue my interests and find a career for myself. I’ve taken care of you while you achieve your dreams and I don’t want to be trapped with you anymore, Carl. I’m going home, I’ll be out of the house by tomorrow morning. Expect divorce papers.” Cheryl stood up, and stormed out of the room slamming the door behind her.

Carl sat down on the floor fighting back his tears, but they broke through and dripped onto the carpet. “Happy anniversary.”

|

Untitled (fog)

Gregg Dotoli

dawn spawns smoky fog

brackish herring deep sense

tidal reverse beneath warm salt air

|

Gregg Dotoli Bio

Gregg Dotoli lives in New York City area and has studied English at Seton Hall University. He works as a white hat hacker, but his first love is the arts.

His poems have been published in, Quail Bell Magazine, The Four Quarters Magazine, Calvary Cross, Dead Snakes, Halcyon Magazine, Allegro Magazine, the Mad Swirl, Voices Project, Writing Raw and Down in the Dirt.

|

Consent

Charvae Johnson

The tension loosens from my fingers as I breathe systematically. This is it. We’ve done it.

“Babe, knew you could pass the initiation. Well done. Not bad technique either.”

My eyebrows knit together, I look at Lucas. I chuckle nervously. “Yeah, it feels just...fantastic.”

“Look, now, now we can relax a little. Just relax our nerves and wait until the surprise happens.”

“Okay. Are you sure we are okay here?” I try to relax my breath as I bring the car into park.

“Yes, we are fine, you are fine.” He reaches over from the passenger seat as he turns my face to his. I let him.

I nod. “I hope you’re right. This wasn’t easy and if this was found out...”

Lucas finishes, “There’s no turning back, yes, I told you this Terry, so relax.” He brings a drink from his pocket. “Here, has a drink.”

I look to the drink, then back up to him. “Sure, “ I said, though he’s already noticed my hesitance.

“Terry, “Lucas said, “What are you so scared of? I am not one of those guys. You just need to trust me. You need to relax, and this can help you relax. Okay?”

Tears begin to fall as I swallow the lump in my throat, then I look to Lucas as the promise glows in his eyes. Maybe this drink will make the pain go away...

I wake up in the back seat, inebriated and lethargic. My mind guides my eyes above me as they find Lucas again. He looks to be rocking against me, I let him.

“I’ve always wanted this, you know that. You passed the initiation, and I am your prize. Just had to convince you a little,” Lucas said. He moves down to my ear, as whispers sweet nothings as his taut body moves with me.

“You’ve wanted me? I never knew...” My eyes drift open and closed. This guy is amazing, and it feels so good. I bring his body closer, revealing my neck unconsciously.

“Yes, I have. I always have, and will be the only one who gets to have you.”

“Why?”

“Questions will never stick to you right now baby, just give into me and let me do what I do best.”

I moan in response. I’ve never felt so wonderful. I hope I can remember this in the morning, my body yields into his desires as I accommodate my own. I love this...

I look down from the driver’s seat, my torso throbbing, there is red there, and my shirt looks.

I glance to a note, as my mind fades in an out of consciousness, Lucas is no longer here.

Baby, you helped me build so much tonight, I wish I could be here to thank you, but I had to go. And had to tie up some loose ends. You have to understand why things had to end like this. You witnessed and participated in a murder. You’re a little girl sweetheart. I couldn’t let you live with doing something that is only meant for the big boys. So I did the honors, and your suffering will end soon. I promise that you won’t be held responsible, and you will soon join your brother, who paid in the same way. Money is a drug, that cannot be quelled, and this was the only way. I was even falling in love with you. But my job came first so... I hope you can forgive me if you meet me in paradise...

The paper crumples, oil falls, a lighter clicks, though my consciousness doesn’t yield me to care.

My mind grows hazy, my body weakening. He’s killed me, and I can’t turn back. I feel my vision leaving, I lay against the cup holders, I’d rather no one see me die.

This was the best night of my life, and the last. Lucas gave it to me, and I let him.

|

feel

Janet Kuypers

haiku 2/15/14

I feel nothing but

the intensity you feel.

Your thoughts cut my face.

|

Honoring the Dead

Greg Mahr

Mother was cold. Maureen could feel Mother’s chill from across the room. Mother knelt by Father’s body, now eight days dead. The Irish tradition that called for a Saturday funeral was less convenient when the death was on a Friday, and the wait for this day seemed endless. Maureen rushed to her Mother’s side to warm her. The pallbearers gathered, and in a few minutes it would be time to close the casket for the last time. Maureen put her arms around Mother. She draped her sweater over her Mother’s shoulders to warm her up. She ordered Jeff to bring Mother a heat pack. She liked to take care of Mother, and she especially liked it that everyone could see her taking such good care of Mother. Maureen started to sing the first few notes of “When Irish eyes are smiling.” No one joined in. It was uncomfortable, even for Maureen. The notes were false, she needed a chorus to back her up. Mercifully, Mother sang a few bars. Maureen was finally satisfied; she was a good daughter and everyone knew it.

Maureen noticed the rosary in Dad’s hands as the hearse driver began to take the flowers from the rented coffin. Maureen watched her sister Maeve stare at that same rosary. Stern and cold, angry already, Maeve marched to the coffin. “What about the rosary?” Maureen asked her.

“It’s all set,” said Maeve.

“What do you mean its all set?”

“I mean its all set.”

By this time the eldest sister Nuala joined the fray at the coffin. Mother stepped back a bit and smiled feebly toward the embarrassed crowd of family and friends. The whispers of the three daughters grew louder and louder, their hissed shouts filling the sacred space.

“That rosary shouldn’t leave the state, you can’t take it with you to Wisconsin,” Maureen cried in a shouted whisper.

“Mom said it should go to the oldest grandson, and that’s my son,” Maeve declared.

“No, I rescued it from the trash when Dad threw it away in the nursing home. None of you came to visit him as often as I did, it’s mine,” Nuala announced.

They all pulled at the rosary. Dad, eight days dead, sinews tight with rigor mortis, held on fiercely. They fought not for the value of the thing, it had none, neither real nor sentimental. The rosary was valuable because someone else wanted it. They fought so someone else would not get what they felt should be was theirs.

In a happier day Dad would have ended the tussle definitively. “Get the feckin’ strap, I’ll whup the three of yurs arses raw!” Father was Country Irish, and those were his daughters. His was not the Ireland of Yeats, Shaw and Joyce. Not Dublin, but the peat bogs of Kilkenny, a land of failed farms, hunger, liquor and violence. Patrick converted them a thousand years ago, but civilization was accepted only reluctantly, for an hour on Sunday. “When God made time he made plenty of it,” Country Irish would say as they drank and fought and halfheartedly farmed the exhausted land. Sometimes the crack of the strap on flesh seemed the only way to keep the devil at bay.

In just a few hours, in a grey unmarked building, miles away from the crowd and the family, gas flames would hiss to life and Father’s body would be consumed in a fiery furnace. His formaldehyde soaked flesh would be transformed into a cloyingly sweet smelling but toxic vapor that would drift out a narrow chimney, then slowly and expectantly inch towards heaven.

The daughters finally pried Dad’s fingers apart. Maeve had the best hold, pulled the rosary away first, turned around and hid it in her purse. Nuala glared at her. Noticing that they were both distracted, Maureen quickly grabbed the wooden crucifix that decorated the inside of the coffin, hid it in her hands, then scurried back to the crowd, her theft unnoticed. Triumphantly, she told Jeff to hide the crucifix in her purse. The funeral was going well after all.

|

ends

Janet Kuypers

haiku 2/15/14

Tying up loose ends,

she paid bills, bought her son clothes.

Then she killed herself.

|

The Epicenter of Sin

C.L. Coffman

The house sat unremarkably at 600 O’Neill Street for some sixty years before it transformed into so much more. The original owner widowed at a young age, lost his only child shortly after, and became a hoarder. When he lost the ability to care for himself, he was forced to sell, but the seeds of looming depression were planted and fed the depravity that would soon live in the house. When the family first arrived, the house was painted a putrid yellow with awful red shutters. The yard was overgrown and the white stone garage looked as if it would collapse at any moment. Still, the peculiar family bought the property and began to renovate it. They turned it into a place that would become infamous, an epicenter of sin for a small city.

The family consisted of five. The mother should be canonized, she loved everyone with all her heart, yet was still driven slightly insane when left for a teenage babysitter. She took care of all who stayed under her roof, yet slept alone most nights in the master bedroom. The unambitious stepfather was once known as a brilliant mechanic but preferred cooking methamphetamine to working on automobiles and could rarely be found sleeping anywhere if he happened to be present. The wise-junkie-indigent uncle couldn’t resist the spike and its sweet relief. He slept on an air mattress on the living room floor until he harpooned it chasing an invisible foe coming off an 80 hour meth binge. The oldest boy was considered a money hungry bastard who would do anything to turn a buck. He shared a small room with his younger brother until mustering up the courage to escape. Lastly, the youngest boy was a lunatic dope-head poet who didn’t give a shit about material possessions and loved to gamble. Though this story isn’t about them, without them there would be no story.

The house attracted all sorts but mostly fiends looking for some sort of a fix. It harbored runaways until they were ready to go home. You could hear anything from terms like hosing down the meat curtains or tenderizing the baby barrel to heated debates on politics, music, love and philosophy. You could always find someone willing to gamble on anything from cards to darts to foosball to all things conceivable. The lights were always on as someone was always awake and in most cases welcoming. Age wasn’t a deterrent. The house catered to all, from honor students to a slovenly amputee biker chick. Those who managed to find the house found comfort in its lawlessness and will always remember it kindly.

After the family arrived, they sided the house grey with black shutters. They filled the yard with random junk and broken down cars. They killed the grass, and within a few years, the house began to radiate with a near visible pulsing tone of gluttony. There were always little ankle-biter dogs dragging strange oddities home, including the hindquarter of a deer, which the family marveled in watching the tiny dog drag home for nearly a week. In front of the house, you would find an assortment of vehicles on any given day, but a blue 1972 Impala with two curious bullet holes was always present. The dilapidated garage became a cook house and you could smell the crank brewing from a block away.

Walking inside was overwhelming for most. Some sort of commotion was always afoot and an unmistakable sense of uneasiness constantly threatened the delicate balance of the home. The house stunk of dog, stale smoke, and liquor, but it was masked at dinner time by the smell of the most delicious cooking many ever had the good fortune to eat. Each room in the house held similarities. They were generally clean but showed signs of violence, and you could find a TV, ashtray, drugs, drug paraphernalia, and copious amounts of pornography in all of them. Most who passed through were more amazed by the amount of porn than the casual lay about of pipes, needles or the pharmaceutical company like collection of prescription medications. The ominously sticky basement was equipped with a makeshift bar and held the most evidence of the carnage that took place in the house. It was not uncommon for the family to find random friends, and sometimes outright strangers, sleeping down there in the morning as that is where all nights, and in some cases, weeks ended.

The house saw countless law enforcement agencies pass through its doors over the years and even more criminals, yet no one was ever arrested there. Still, patrons of the house can be found in no less than ten different penitentiaries across the country, including Leavenworth. So many laughs were had, so many tears were shed, and so much blood was spilled there. Just like all curiosities the house faded away. The saintly mother passed. The stepfather was imprisoned. The indigent uncle got his shit together and made a little progress with his drug habit. The oldest boy blew town before things really got weird and tries to deny where he came from. The youngest boy went mad and spiraled downward. Today, the garage is gone, the house is a new color, and there is rarely anyone there. It has been years since I’ve been there but I will always remember it for what it was, a place without borders, where anything was possible, and judgment rarely passed.

|

The Old Railtrack

Samuel T. Franklin

Old railtrack sweating rust at sunset,

abandoned and broken and forgotten.

A strange sight in the city of trains,

like finding lilies growing in a ditch.

Sunfried asphalt broken in chunks.

Plywood in the windows of foreclosed houses,

shrieks of distant trains ghostcalling

through dark trees and the tunnel

that piped beneath the nameless tracks,

the concrete steps that led me down

into that cool chute beneath the earth

where shadows choked sunlight.

Where my flashlight lit

like a match in a cave

the graffitied and painted scrawlings

crawling all down that stone gullet,

where urban tattoos marked concrete

with rhymed names and accusations

and jungle-drawings of the monsters

that lurk on the edge of town,

the syringes and red eyes and rotten teeth.

Where quotes of dead poets

and shreds of cannibal longings

and half-finished prayers

were etched, offerings to a void

by unknown city souls, lonely roamers

drawn to the gleaming metal bones

rusting in the weeds,

where the world

and what lies beneath

blend together

in bitter harmony.

|

The Econlockhatchee River

Jeremy DaCruz

It was an unbearably hot summer in Orlando, with the temperature in the upper 90s. It was my first time back since I moved to Asheville, NC and I was there to see my old friend, Ben.

We drank some strong drink, then idly considered how to best occupy the rest of our day. Ben suggested we go down to the Econlockhatchee River to cool down. I assumed we would use a canoe, but then Ben bizarrely suggested getting a kiddie pool from Wal-Mart. In the huge, horrible store, a purgatory of endless aisles, Ben quickly set his sights on an air mattress, and I picked out a kiddie pool. Why didn’t I notice that Ben didn’t follow his own suggestion? Anyway, I bought some cheap beer and we were off.

Near the river, we started pumping up our unconventional vessels. My kiddie pool had a strange nozzle that made inflation difficult. After half an hour of work, the kiddie pool barely a third inflated, I suggested that we just share the air mattress. Ben, as the veteran, declared that the air mattress would indeed be able to hold both our weight and the beer.

People gave us strange looks. Two guys, one short and fat carrying cheap beer, the other tall and lanky toting an inflated air mattress. We walked barefoot on the gravel path, wincing as sharp rocks sent stings of pain through our feet. We dodged hanging moss and cypress trees, then crossed a small footbridge, eager to begin.

At the riverside, we flopped the air mattress into the water. The sky was darkened by an approaching storm; the river was a deep, dark, blue. We sat back to back, with the six pack wedged between us, water flowing over our hips. We shoved off and let the current take us.

The water was murky from recent rainfall, its surface completely opaque.

“Do you think there are alligators in this river?” I asked.

After a long pause, Ben replied, “Maybe?”

I took a swig of beer.

We floated along and caught up on each other’s lives. I began rambling, as I often do, about the constant ups and downs of my love life, my recent move to North Carolina, and my family vacation to Ireland. Ben then imparted some sage advice about how to maintain long distance relationships as he had just returned from a summer in Bulgaria with the Presbyterians. The banks were sandy and lined with sagging trees. Our craft lilted along, and while the dark sky created a tunnel effect, we drifted towards our destination.

By the time we had reached the rope swing, a spot we always favored in the past, we only had two beers left and had taken to using the empty bottles as especially awkward, makeshift oars. I noticed that the waters had risen so high that the beach on the opposite bank was completely underwater. The darkened, swollen river had a post-apocalyptic aura, and we were piloting Noah’s Ark with empty bottles of IceHouse.

We docked our air mattress against the riverbank and Ben, determined to use the rope swing, climbed ashore using the roots of a massive cypress. Just as I was about to do the same, with the rope swing dangling above me like a carrot on the end of a string, I heard splashing, turned my head, and saw a big scaly tail fling out from under the water. I scrambled much further ashore.

Normal watercraft, such as canoes, have no real problem with gator-infested water. Except we didn’t have a normal watercraft.

After twenty minutes of staring intently at the water, we had convinced ourselves that the gator had moved on, boarded our air mattress and began to paddle across the river. Just after we got to the midpoint between the two shores, a gator’s eyes popped above the water, then back below 5 feet in front of me. I shrieked Hail Maries, my Catholic faith surging. We thrashed, and Ben sputtered that alligators are shore predators. We flung ourselves ashore, and Ben climbed up first, then I followed, dragging the mattress with me.

Back on the path, which is within a few feet of the riverbank, Ben mused, “I don’t know if this makes it better or worse, but that might have been one gator following us, or multiple gators.” I was thankful to be back on a familiar trail that I knew would lead us to the parking lot.

We journeyed back to the car, over the bridge, hearts racing and nerves shot. Our lives, normally sequestered within the world of undergraduate academia, were just interrupted by something extraordinary. We lived lives oriented towards boosting one’s resume, networking, and making perfectly mundane choices. We were fools, but many youthful decisions, fraught with danger, are misguided attempts at heroism. The heroic change the world, but fools become tragedies. We, not dead, arrived at the car feeling like heroes. We experienced the river. We were friends. We out-navigated alligators, sort of. We were convinced that day God protects fools, drunks, and children. We were all three. Well, maybe not drunks.

|

Red Clover

Todd McMurray

The car was a thing of menace and beauty, awaiting her return in the silence of a rain-scented evening. Its elegant components gave it surreal life. The chrome grill glared like the bared teeth of some mythical creature. Its quad headlamps were arachnid eyes, and the chassis tapered back into a pair of pointed fins, a monstrous metal bat. Pitch black, unmoving, her fantastic chariot sat. The night breeze whispered all around it.

Undressed, Miyuki stood before a second story window of the abandoned tenement, gazing out through the hazy, splintered pane at her beloved automobile below. It never failed to leave her breathless. Her nimble hands danced across the slopes and hollows of her body as she admired the machine’s moonlit contours. Miyuki considered them not unlike her own: sleek, inviting... classic. In the glass, her translucent reflection coalesced with the very sight of it, and they were one. Porcelain skin and ebony iron. Throbbing heart and smoldering gears.

It had been ages. Miyuki and the car shared a sinister history, although to her it was merely deliverance. How many had she spirited away? Miyuki prowled her memory, a kittenish smile widening with each successive recollection. How many lovers had she pinned to the crimson leather of the backseat? How many had she ignited in lascivious throes, only to snuff them out like so many dripping candles? She was bewitching, a woman of many weapons, and chief among them was the black machine. The car was her armored world, her spider web. With it, she coaxed countless young girls to their unknowing demise. Misanthropes. Doe-eyed innocents. Thrill seekers. Hitchers. Miyuki had no “type,” per se. Each one was a delicacy, and she referred to them as “morsels.” Men held no fascination for her. She deemed them simple things, animals with crude designs for life that scarcely enticed her. Even their flavor in her mouth seemed superfluous. No, for Miyuki, the female form was ambrosia. Their musk at the height of passion was like nectar on her lips, and their blood-soaked bodies after were cakes adorned with a confectioner’s flourish. Every kill was savory, and her precious vessel whisked her to and from each one, the only witness to Miyuki’s maleficent deeds.

A pained, withering sound shook Miyuki from her entrancement, and she turned, expressionless, to face it. The decrepit room flickered in the halo of a single, large candle. Discarded articles of clothing threw long, misshapen shadows into the corners. Miyuki stepped into the center, her naked body wreathed in pale orange, and knelt to appraise her gruesome handiwork. Kate. This one had been young, but willing. The wild-eyed blonde had consented to having her wrists bound to her ankles, and the prospect had Miyuki swooning. She took great care in pleasuring her, then snapped like a viper on some hapless rodent. Now, the snow-white blankets Kate lay upon were a pyre of deepening pink. Miyuki had lacerated her abdomen in artful swaths that resembled, without question, a four-leaf clover. The image was, and always would be, Miyuki’s obscure nom de plume. “Clover” was a nickname. However, its origin was the only memory Miyuki failed to pull from the howling recesses of her distant past. Try as she might, she could only recall an instance or two of its usage. Like her father whispering “my lucky little Clover” on the occasions he would crawl into bed with her, coarse fingers probing. Or oafish boys chanting “Bend over, Clover!” whenever they surrounded her in a bathroom stall after school. These remembrances, too, had become a soft blur as of late. It mattered not. Miyuki’s bloody badge stood, her solemn signature on a message to no one in particular. She would not forget.

Kate was stirring, but to little avail. Life was leaving her. Gagged with her own lingerie, the muted murmurs of her fading pleas eventually ceased. Her once wild eyes mustered a confused glare at a genuflecting Miyuki, then rolled backwards into a milky gloss. Miyuki smiled with affection, stroking Kate’s tousled locks, and placed a lingering kiss between the unfortunate girl’s breasts. Then, as was her wont, Miyuki cradled the victim and recited her death poem:

Hush, child of sugar. Hush, child of spice.

Hush, child of libertine, earthly device.

From this world I take you. Cast unto the next.

In absence of Adam, let Eve go unchecked.

Argent and always, these wings I bestow.

Upon them, surrender to heavens unknown.

We meet but to part, for now must it be.

My shadowy steed cries a portent to me.

That long we may travel, of tethers bereft.

Your seraphs incarnate. Your saviors in death. |

Miyuki rose like a phantom and hovered about the room in familiar, delicate measures. She collected each piece of scattered clothing and placed them in a drawstring garbage bag, opting to don only a black silken trench coat. It was her favorite, the fabric teasing her bare skin. The candy-red stilettos she wore had never come off. Lastly, the blade. Still it shimmered in the room’s dying glow, streaked with Kate’s final, futile essence. It slid with cold precision into Miyuki’s left pocket. Then, as though a mother putting an infant to bed, she spared her erstwhile playmate a tender glance before extinguishing the candle. Miyuki exited without a sound.

Out and into the night, Miyuki slithered towards the car, her obsidian sentinel. She deposited her bag in its ample trunk, and paused to survey her domain. The desolate outskirts seemed at odds with the brilliant canopy of stars above them. They always had. Miyuki was well acquainted with them. Miles from any ears to hear, many a seduction had ended in this gothic hole of a place. This evening, however, she bade farewell to their crippled structures. Miyuki knew better than to remain in any one location for long, and stepped into the car. At a turn of the key, it aroused with a sonorous purr, sending a welcome sensation along the length of Miyuki’s slender figure. She gripped the wheel and bit her lip, revving the engine in rhythmic bursts. Her past dwindled behind her as she accelerated into a lightless horizon. The car embraced her in a muscular hum, every inch of pavement yielding to its ominous frame. Miyuki cooed. There was only herself and the black machine. They were both insatiable.

|

The Vision

Patricia Hardesty

He sat there in his shiny new beamer on the side of this God forsaken road in the middle of the night thinking back over his life. The events that had led him here. Roman was a hard worker. A self-made man. He had endured ridicule and people telling him he would amount to nothing because he came from a poor family. So Roman had done the only thing he knew to do and that was excel in school. He learned everything, soaked it in like a sponge, found out he was good with numbers. In high-school he he pushed himself in calculus and algebra and football. His football team made it to state every year because of him. He landed a scholarship to college and left the minute he graduated and never looked back on this tiny black-hole of a town.

Twenty years he had been gone. Living the life everyone thought he would never have. He had a penthouse in the Village, a new BMW every year, beautiful women begging to be with him. He swore he would never come back. Never think of this place again, but two days ago, Old Man Gene, how he got his number Roman would never know, called him up out of the blue to tell him his mother had passed. Old Man Gene was still kicking. Roman remembered him being old when he was a kid, sitting out front of the local barber shop everyday proclaiming to see the end of the world. Everyone thought he was crazy of course, but a few times he had been dead on when telling someone they were going to die. He had told Roman over the phone that he had told Jeanie she needed to get to the doctor, that she was going to have a heart-attack, but she wouldn’t listen and now he was having to call Roman with the bad news.

So, here he was. He had to follow his GPS to get back here. He had shoved the memories down so far; he couldn’t even remember how to get here anymore. The sexy voice had led him down this strange back road in the middle of the night with fog rolling in all around him. Then, about three miles down the road his GPS had given a guttural choke and died, then his car did the same. So, now he was stuck. Thinking back over the conversation with Gene, Roman was pretty sure he remembered him telling him something about not coming at night. Maybe he should have listened. Good one Roman, now you’re going to start listening to an old man who by all rights should be pushing up daisies himself by now.

Shaking it off Roman got out and decided to walk back to the main road. Someone might come by and see him and give him a ride or at the very least, he could get cell service and call.