welcome to volume 97 (August 2011) of

down in the dirt

internet issn 1554-9666

(for the print issn 1554-9623)

Janet K., Editor

http://scars.tv.dirt.htm

http://scars.tv - click on down in the dirt

Note that any artwork that appears in Down in the Dirt will appear in black and white in the print edition of Down in the Dirt magazine.

|

Order this issue from our printer as a 5.56" x 8.5" ISSN# paperback book: or as the 6" x 9" ISBN# book “Catch Fire in the Treetops”: |

![]()

The fire catches in the treetopsFritz Hamilton

The fire catches in the treetops, burning

return to the ashes from which they sprang/

the injustice, but God is a smoldering ingot in

perdition gushes from his bellybutton to

cries to Him about his losses, but God-the-devil

futile haranguing until he too is ashes his throne ... !

|

I climb into my radio &Fritz Hamilton

I climb into the radio &

last rejection, a lethal injection/ this

solves all its social problems by

any other nation including

leading the way, just like we do

ever since that great humanitarian

the joint (98 percent were black,

decades later we also throw

enhance the building industry in

education, & our standard of living

the capitalists have it all as

the sheep accept their devolution &

man IS THAT WE WERE

!”

|

Internet Issue Bonus poem

Fritz Hamilton |

Internet Issue Bonus poem

Fritz Hamilton |

Tinker-Tinker-MeChristopher Hanson

I wake up and turn me on

|

“The man with many names.” |

![]()

It Could Happen to YouRoger Cowin

A man enters a crowded bar,

A young woman goes for a walk in the

An apparently happily

A Muslim man from Pakistan

A young woman falls asleep in the backseat of a car.

I stared at the closed casket, wept as they placed her

|

![]()

Saber In StoneDenny E. Marshall

A pen a short sword

|

![]()

NoosedKyrsten Bean

I remember tan cargo pants, chicken feet & dumplings in soup Don’t make eye contact, don’t smile. Meanwhile, back in the hospital, she hung her bed sheet on the door.

I remember she drew mushrooms & rainbows

I had punched a hole in the wall, once. And when the staff asked who had done it,

The door was six feet high. When she picked up her feet–after

|

Kyrsten Bean BioA poet, musician and writer, Kyrsten had been stacking piles of poetry in her living spaces for 29 years. At some point she decided that her words were lonely – they were suffocating stacked three feet high in old notebooks. She is on a crusade to find a home for her homeless compositions of words, and spends all of her free time searching for havens. She lingers outside the fringe, trying at times to get a real job, only to throw in the towel again and go back to creating.

|

![]()

Hiding in the Shadows.Matthew Roberts

Stay still, stay quiet

|

| Janet Kuypers readin the Matthew Roberts poem Hiding in the Shadows from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine |

Watch this YouTube video read from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine, 08/09/11 live at Chicago ’s the Café open mic |

![]()

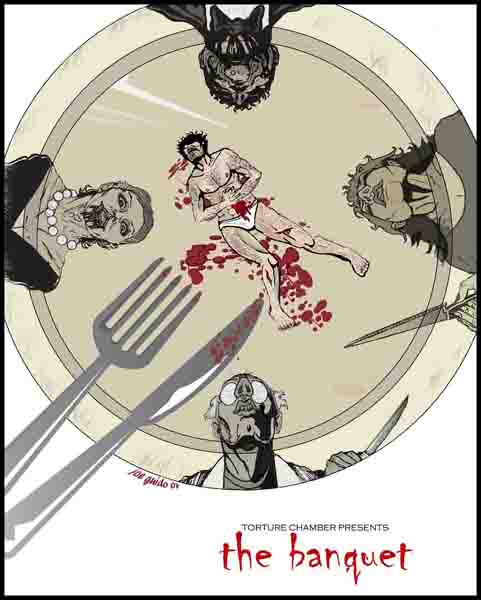

Click here for the comic

the Banquet

by Victor Phan

![]()

FlashpointAsh Krafton

All it took for Debbie to go from hero to victim was a simple point and click. A tap of a finger, a tiny nudge forever changed the spin of her world.

|

Ash Krafton BioPushcart Prize nominee Ash Krafton is a speculative fiction writer whose work has appeared in several journals, including Niteblade, Ghostlight Magazine, Expanded Horizons, and Silver Blade. Ms. Krafton resides in the heart of the Pennsylvania coal region and lurks near her website Spec Fic Chick (http://ashkrafton.com).

|

![]()

The ClosetMel Waldman

I live in a closet. But each day, I leave my little home and the safety of my microscopic universe. I saunter off into the labyrinthine streets and walk the tightrope of life and death. I don’t belong. Do you?

|

BIOMel Waldman, Ph. D.Dr. Mel Waldman is a licensed New York State psychologist and a candidate in Psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies (CMPS). He is also a poet, writer, artist, and singer/songwriter. After 9/11, he wrote 4 songs, including “Our Song,” which addresses the tragedy. His stories have appeared in numerous literary reviews and commercial magazines including HAPPY, SWEET ANNIE PRESS, CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES and DOWN IN THE DIRT (SCARS PUBLICATIONS), NEW THOUGHT JOURNAL, THE BROOKLYN LITERARY REVIEW, HARDBOILED, HARDBOILED DETECTIVE, DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE, ESPIONAGE, and THE SAINT. He is a past winner of the literary GRADIVA AWARD in Psychoanalysis and was nominated for a PUSHCART PRIZE in literature. Periodically, he has given poetry and prose readings and has appeared on national T.V. and cable T.V. He is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Private Eye Writers of America, American Mensa, Ltd., and the American Psychological Association. He is currently working on a mystery novel inspired by Freud’s case studies. Who Killed the Heartbreak Kid?, a mystery novel, was published by iUniverse in February 2006. It can be purchased at www.iuniverse.com/bookstore/, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. Recently, some of his poems have appeared online in THE JERUSALEM POST. Dark Soul of the Millennium, a collection of plays and poetry, was published by World Audience, Inc. in January 2007. It can be purchased at www.worldaudience.org, www.bn.com, at /www.amazon.com, and other online bookstores or through local bookstores. A 7-volume short story collection was published by World Audience, Inc. in June 2007 and can also be purchased online at the above-mentioned sites.

|

![]()

BlitzkriegCarys Goodwin

The situation underground was comparative serenity to the hysteria of outside. Bea sat in a huddle, pressed against the ever-vibrating walls of the bomb shelter, watching without seeing. It had been less than two hours since the ordeal began, but each minute felt like years, and Bea’s thoughts plagued her in an incomprehensible swarm. She closed her eyes and leant back until her head made a dull clunk against the wall. Under her breath, she began to murmur the notes to her favourite piece of music, just loud enough to hear the tune wavering from her lips.

Bea is bored. She knows the answer to her teacher’s question, but feels compelled to give the other girls a chance. Judging by their faces - expressions of embarrassed ignorance - they can’t figure it out. The teacher surveys her class, an interrogative glare, before landing on Rose in the front row. Tiny thing, as delicate as her name.

Bea fell out of her reverie to an awful scream. A small girl had been dragged below by one of the teachers and was seemingly unconscious. Her face was smeared in red, and, from what Bea could see, one of her arms was missing. It took Bea longer than usual to understand, but when she did, she wished she didn’t. For the girl was none other than Rose, the flower, crumpled into an unnatural heap, cradled in the arms of the teacher who tried to rescue her.

The bread Bea is eating is disgustingly dry, as per usual. She spits out the mouthful in despair, wishing for the days when sugar was more than a myth. The action earns an ‘ahem’ from the supervising teacher. Her friend Allie giggles into her mushy peas, and they exchange glances as the teacher begins to approach. Smoothing her dress, Bea prepares to debate the nutritional quality of stale bread in her usual argumentative fashion, but she is distracted by the ground starting to rumble.

Someone placed a hand on Bea’s back as she vomited. After pausing to make sure she had finished, Bea looked up and saw that it was her teacher, the one whose class she had been in before lunch. The teacher’s hair was a mess of straw-like strands, her lipstick smeared against her cheek. But she was familiar, and that was enough for Bea. Tears began to slop down her cheeks, mixing with the sweat that already glossed her face. Her teacher pulled her in tightly, whispering ‘Beatrix, oh darling, hush, hush,’ into her ear.

|

![]()

Off CameraLaine Hissett-Bonard

I didn’t want to admit it, but I knew I was falling for him even before he came on my face in front of a camera.

for their invaluable guidance, which made this story possible.<

|

![]()

A Lesson in AutonomyEmma Eden Ramos

Bryn watched as her father entered the facility. She picked at a scab on her knuckle, then looked at the on-duty supervisor for assurance. This particular meeting was a condition of her approaching release. Otherwise, Bryn would never have agreed to it.

|

![]()

A Single DayKaren Alea

There have been times when I’ve bought lumber that was smooth and white on one side and gaped and pickled on the other. But I always put that marred side where it would face inside, letting the good side, that faultless side, face the world. It was a matter of economy, though it made my gut prickle with bile.

We rented a small cottage near the square, surrounded by overrun lawns and houses rented to college kids. I couldn’t understand, still don’t, why the area is so neglected and people would rather build cookie-cutter two stories with no land. These homes were built by men who thought each part of the house through. They might lack a modern comfort, but nothing that a hammer and some nails can’t fix up if someone is willing to put their own mark on it.

In May Janet got pregnant.

Janet’s female organs failed after that. Something genetic where cells kept growing, making her huddle over the dinner table. The doctor told her he’d have to take it all out. At work I took it out on boards, hammering straight through a piece of pine and having to throw it out on the pile.

I lived for Sundays. Janet and Rainbow were my religion. We’d lie on the bed, the sheets cool and clean from a Saturday wash, and play with her curls and knees and toes. Almost three, she still had fat layered around her joints and when she jumped on the bed her legs jiggled.

I didn’t get any walk-ins. It wasn’t that kind of place. So when Hollander opened my door and gave the shop a rectangle of clear air for a few seconds, I thought he was lost, needed directions.

I hear she’s a tomboy now. The jail psych said that happens sometimes. Girls feel they are not pure like the other girls and identify with the boys more.

|

Karen Alea Biowww.karenalea.com

Growing up in South Florida with light skin and red hair, I found myself a Cuban-American spy, getting to look into my own culture with one foot outside. I laughed along with the wetback jokes during the day and ate arroz con pollo with my Abuelo at night. Living in two worlds at a young age, I have always been interested in the emotional and social differences of world cultures. I have traveled/worked in Cuba, India, Haiti, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Thailand and Australia.

|

![]()

HallocksToni M. Todd

A real pair of Levis, not the J.C. Penney brand she always wore. Adidas, too, leather, with green stripes, not the vinyl knockoffs. These were the things Megan planned to buy with the money she earned working this summer’s berry season. She’d been thinking about it for weeks, but her enthusiasm was tempered by an unpleasant surprise. Megan stood, her rear-end to the bathroom mirror, looking over her shoulder. Her eyes flooded with tears.

The berry-mobile, as the kids called it, was a dingy, rattle-trap-reject of a bus from the local school district. This was the Queen of All Saints platoon, with all of the strawberry pickers hired from Megan’s school. The farmer was a member of their parish. Most of Megan’s classmates worked the fields. Some needed the money to help their families, but most these days worked to earn spending cash for clothes, skateboards and bikes. Berry picking was a Willamette Valley tradition. Their parents had picked as children, so they picked, too.

The sun peeked over the distant mountains as the bus banged across hard-packed dirt and rocks, mangling dandelions that sprouted adjacent to the berry patch. Megan dropped down the steps into the early morning chill and inhaled the familiar smell of damp earth, wet leaves and strawberry juice. She rushed to the stacks of empty crates and carts, putting quick distance between herself and the line of kids exiting the bus. Lines of green and brown stretched across the field, each bush indistinguishable from the next. There was the giant oak under which she and Katie would break for lunch, shaded from the midday heat. A port-a-potty stood sentinel over the berry patch, at the opposite end from their tree. The checkout stand was near the bus, where pickers would bring their crates to have them counted, their pay tickets punched. At the end of the day Angela, the oh-so-serious platoon leader, a senior at Sacred Heart, would peer through stringy, dishwater bangs to sign off on your card, dock you if you’d committed any infraction, then collect the document to submit to payroll. Paydays were Fridays. Cash. There were those rickety, aluminum pushcarts, like wheelbarrows without bins, rails dented, metal wheels untrue.

Megan did her best to fill the silence between them as the girls picked through the afternoon. “‘If God didn’t make the little green apples...’ Come on, Katie. You love this song. ‘No Disneyland or mother goose and no nursery rhymes...’”

The bus was crammed with grungy children, dirt caked to their butts and knees, red and brown smudges on their sun-burned cheeks. Katie sat quickly, in the front next to Gretchen, forcing Megan to continue down the aisle, where she found a seat across from Jasper, two rows back.

|

![]()

The Invisible SelfCarl Scharwath

Early molecular loneliness impregnates,

City swells beneath footprints,

Abandoned in yourself awakening,

The self becomes visible,

|

Carl Scharwath BioThe Orlando Sentinel and Lake Healthy Living Magazine have both described Carl Scharwath as the Ürunning poet.Ý His interests include raising his daughter, competitive running, sprint triathlons and taekwondo (heÙs a 2nd degree black belt). His work appears all over the world in publications such as Paper Wasp (Australia), Structo (The UK), Taj Mahal Review (India) and Abandoned Towers. He was also recently awarded ÜBest in IssueÝ in Haiku Reality Magazine. His first short story was published last July in the Birmingham Arts Journal. His favorite authors are Hermann Hesse and Edith Wharton.

|

| Janet Kuypers readin the Carl Scharwath poem The Invisible Self from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine |

Watch this YouTube video read from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine, 08/09/11 live at Chicago ’s the Café open mic |

![]()

...in the nights of goodbyeAaron Bragg

It really couldn’t have been a better day to spread ashes. Not a cloud in the sky, but what sunlight actually hit the ground was first filtered through a leafy lattice of aspen and Sitka spruce. In all directions, everything was cast in a deep emerald green—even the water, whose mirrored surface was only occasionally broken by rising trout. If Bud were still alive, rather than sealed in a nondescript cardboard box in the trunk of Roberta’s ‘84 Chrysler LeBaron, he might have packed his fishing gear: it was this place, less than five miles from the Pacific coast on Oregon’s Alsea River, that was Bud’s favorite fishing spot, and Roberta figured he might like to commence eternal life by floating, ever so gently, downstream toward the ocean.

The funeral was in February, a couple of weeks after Bud’s heart stopped mid-surgery. There was no casket, no body; the service seemed a little like church, only more patronizing. That Bud would rather have been on the Alsea than in the sanctuary of Albany United Methodist on a Saturday morning was lost on Roberta, who seemed to relish the attention from parishioners who had met her husband only once or twice. Strange, she thought, that Bud’s doctor isn’t here. Perhaps someone else was dying on an operating table.

It was only 3:30 in the afternoon, but Roberta was tired. Alan and Heather were leaving first thing in the morning. In a few hours, she would be alone after fifty-three years of marriage. There was no one to mow the lawn anymore, she thought. And who will prune the roses this spring? My beautiful yard... She walked down the hallway to her—her—bedroom, closed the door, sat on the edge of her bed, and silently wept.

Alan closed the trunk of his car, looked uneasy for a few moments, and half-heartedly offered to stay a little longer. You know, maybe help clean out the garage or something. Roberta flashed her widow’s smile—it came more readily now—and shook her head no. Alan shrugged and made certain Heather was situated before backing out of the driveway. Roberta didn’t wait: The front door of the house was closed before the car was out of reverse.

It was late April, and Roberta’s widow’s smile was coming along nicely. So was her yard, thanks to a grass-cutting service that came by once a week and the help of some volunteers from the church youth group. The roses didn’t fare so well, nor did her fuchsias, but they were in the back yard where passersby couldn’t see. The oil stain on her driveway from Chuck’s van was at last fading to a light brown, and the appearance of normalcy from one end of the property to the other was overwhelming.

Bud’s ashes had arrived at her home via crematory courier six weeks earlier. The driver, a lanky college kid who checked the number on Bud’s box against a sheet on a clipboard, awkwardly accepted a rolled-up one-dollar bill from Roberta in a clumsy pass. The widow’s smile was flashed—ever so briefly—while the driver shifted boxes in the back of his filthy pickup, mentally mapping out his delivery route.

Alan and Heather, by now tiring of living under the pall of perpetual death, arrived Thursday evening for what they hoped was the last in a series of events mourning Bud’s passing, checked into the same dingy and convenient motel, and awaited the moment. Chuck pulled into Roberta’s driveway late Friday afternoon, strategically positioning the van over what remained of last February’s oil stain.

Saturday morning was warm and muggy. A sense of finality added to the heavy air, and nobody said much. Clothes were packed, suitcases dragged to the front doors of the motel rooms, drawers opened and closed. Chuck had purchased day-old donuts the night before from the grocery store down the street. They were eaten as a greasy afterthought, a means by which breakfast could be checked off the day’s to-do list.

Bud’s last trip to the Alsea River was almost surreal for Roberta, who determined that she’d never come this way again. The route she chose took them first on Highway 20 through Corvallis—where Bud had played basketball at State—then turning on the Alsea Highway just past Philomath. Even Heather found herself lost in the beauty of the Willamette Valley, slowly forgetting the purpose of the journey with each passing dairy farm. Alan delighted in the LeBaron’s on-dash digital mileage report and the remarkable fuel economy as they descended the final grade. Roberta was silent.

A fisherman from Newport discovered Roberta’s body a week later, tangled in kelp and draped over a pile of driftwood on the sand near the mouth of the Alsea. She hadn’t made it to the Pacific, either. Crabs, seagulls, and scores of nameless insects had made identification difficult, so it was a couple of weeks before anyone was notified.

|

Aaron Bragg BioOver the course of his 10-year writing career, Aaron Bragg has published music criticism, news features, a weekly political column, and short fiction. He currently works as a copywriter at a northwest design firm.

|

![]()

An Evening with Cary GrantJ.D. Isip

This is how he remembered it – just like this: an intimate locale, dark and smoky, open stage, a chair and mic, a tiny table with a bottle of scotch, a bucket of ice, and a single crystal glass. This was classy – just like Grant did it so many years ago.

“A team of commandos land in a far off jungle –” John has his hands in front of his face, thumbs and index fingers framing the scene à la DeMille.

Charles and John were cruising down Santa Monica Boulevard, hood down. The city was alive, the club crowd was just emerging – everyone clean-scrubbed, bopping to the music of anticipation, laughing for nothing at all.

Charles’s living room was pristine, unlived-in. He was here maybe two nights a week. Otherwise, he was on the road or shooting somewhere. His sofa, black leather, was brand new. Everything was brand new – and he had been here for nearly two years. He preferred the place off Obispo, where they lived before Chuck moved away for college.

|

![]()

The Only Genuine TruthEdward Rodosek

My faithful TV is waiting for me.

There all women are glorious as goddesses,

There I get to know

I must simply and solely buy

All those splendid new gems

I’ll stay here inside

Yet – only one thing disturbs me:

|

Edward Rodosek BioDr. Sc. Edward Rodosek is a Senior College Professor. Beside his professional work he writes fiction. More than hundred of his short stories and about a dozen of his poems have been published in various magazines in USA, UK, Australia and India. Recently he published in USA the collection of short stories “Beyond Perception”.

|

![]()

Las Cruces MemoriesSheryl L. Nelms

do you

that Sunday morning in July

in the New Mexico desert

you said

I didn’t

remember how your car swayed

because I said

remember how you did dusty doughnuts

do you know how mad I was do you remember anything of that day?

|

![]()

Midlife CrisisTom Fillion

It was nine o’clock when I arrived at Flint’s house in Thonotosassa. His car was there along with another one. I presumed it was Ellie’s and that they had made up again. It looked like she had a different one from her previous visits, a little sportier too. I knocked several times, but there was no answer so I figured they were back in Flint’s bedroom doing what they usually did, knocking knees.

|

About Tom Fillion |

![]()

So Everything Is FineHolly Day

love creeps up like a

it’s quiet and it’s cold

so good going in but

|

| Janet Kuypers readin the Holly Day poem So Everything Is Fine from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine |

Watch this YouTube video read from the 08/11 issue (v097) of Down in the Dirt magazine, 08/09/11 live at Chicago ’s the Café open mic |

![]()

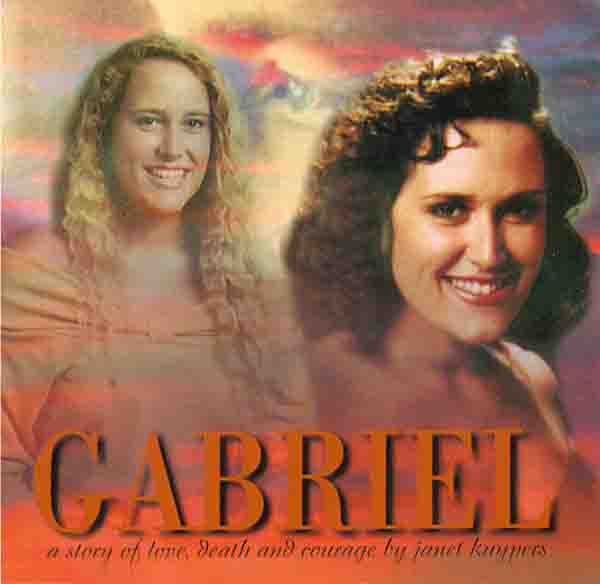

GabrielJanet Kuypers

She had lived there, in her fourth floor apartment on the near north side of the city, for nearly three years. It was an uneventful three years from the outside; Gabriel liked it that way. She just wanted to live her life: go to work, see her new friends, have a place to herself. This would get to Eric sometimes; it would fester inside of him when he sat down and thought about it, all alone, in his apartment, wondering when she would be finished with work. And then he’d see her again, and all of his problems would disappear, and he’d feel like he was in love.

One morning he was sitting at her breakfast table, reading her paper, waiting so they could drive to work. “Hey, they finally got that mob-king guy with some charges they think will stick.”

Eric started to worry. As they car-pooled together to work, Gabriel sat in the passenger seat, right hand clutching the door handle, left hand grabbing her briefcase, holding it with a fierce, ferocious grip. But it was a grip that said she was scared, scared of losing that briefcase, or her favorite teddy bear from the other kids at school, or her life from a robber in an alley. If nothing else, Eric knew she felt fear. And he didn’t know why.

Work was a blur, a blur of nothingness. There was no meeting, the workload was light for a Friday. But at least the headache was there, that wasn’t a lie. She hated lying, especially to Eric. But she had no choice, especially now, with Jack lurking somewhere in the streets out there, winning his cases, wondering if his wife is dead or not.

“Do you still have the headache, honey? Do you want to just rent a movie or two and curl up on the couch tonight? Whatever you want to do is fine, just let me know.” But she couldn’t. And there was no reason she should have.

And then she thinks: “Wait. All I’ve seen is the back of him. It might not even be him.” She took a breath. “It’s probably not even him,” she thought, “and I’ve sat here worrying about it.”

By the washrooms, she stared at him while he took one step away from her, closer to the dining room. Then she felt a strong, pulling hand grip her shoulder. Her hair slapped her in the face as she turned around. Her eyes were saucers. She asked him if they could stop at a club on the way home and have a drink or two. They found a little bar, and she instantly ordered drinks. They sat for over an hour in the dark club listening to the jazz band. It looked to Eric like she was trying to lose herself in the darkness, in the anonymity of the crowded lounge. It worried him more. And still she didn’t relax.

And she drove on the expressway back from dinner, Eric in the seat next to her. He had noticed she had been tense today, more than she had ever been; whenever he asked her why she brushed her symptoms off as nothing.

And she didn’t even have to hear it.

“Three years ago, when I moved to the city, my name wasn’t Gabriel. It was Andrea.

“For the longest time I couldn’t believe that another man, especially one who had the potential for being so successful, was actually interested in me. He was older, he was charming. Everyone loved him. I followed him around constantly, wherever he wanted me to go.

“Money wasn’t a problem for us, he had a trust fund from his parents and made good money at the firm, so I could go to school. But he started to hate the idea that I was going to college in marketing instead of being his wife full time. But that was one thing I wasn’t going to do for him, stop going to school.

“When it was approaching two years of marriage with this man, I said to myself I couldn’t take it anymore. He told me over and over again that he’d make me pay if I tried to leave him, I’d be sorry, it would be the worst choice I could ever make. This man had power, too, he could hunt me down if I ran away, he could emotionally and physically keep me trapped in this marriage. “I found my way two hours away to this city, came up with the name Gabriel from a soap opera playing in a clinic I went to to get some cold medication. I managed a job at the company I’m at now. Did volunteer work, rented a hole for an apartment. Projected a few of the right ideas to the right people in the company. I got lucky.” She told him all of this before she told him that her husband’s name was Jack Huntington.

She brought him home, sat on the couch while he made coffee for her. He tried to sound calm, but the questions kept coming out of his mouth, one after another. Gabriel’s answers suddenly streamed effortlessly from her mouth, like a river, spilling over onto the floor, covering the living room with inches of water within their half hour of talk.

Eric told her that she could have told him before. “I’d follow you anywhere. If I had to quit my job and run away with you I would.” It hurt him that she kept this from him for so long, but he knew he was the only person who knew her secret. He smiled.

She drove into the town she had once known, saw the trees along the streets and remembered the way they looked every fall when the leaves turned colors. She remembered that one week every fall when the time was just right and each tree’s leaves were different from the other trees. This is how she wanted to remember it. >

“Andrea.” She could see her through the brown curls wrapping her face. Another long silence. Sharon’s voice started to break.

They sat down in the living room. In the joy, Sharon forgot about the bruises on her shoulder. Gabriel noticed them immediately.

“No, he’s out playing cards. Should be out all night.”

Sharon moved her arm over her shoulder. Her head started inching downward. She knew Andrea knew her too well, and she wouldn’t be able to fight her words, even after all these years.

“No. It wasn’t easy. But I had to do it, I had to get away from him, no matter what it took. In spending my life with him I was losing myself. I needed to find myself again.” Within forty-five minutes Sharon had three bags of clothes packed and stuffed into Gabriel’s trunk. As Sharon went to get her last things, Gabriel thought of how Sharon called her “Andi” when she spoke. God, she hadn’t heard that in so long. And for a moment she couldn’t unravel the mystery and find out who she was.

Sharon came back to the car. Gabriel knew that Sharon would only stay with her until the divorce papers were filed and she could move on with her life. But for tonight they were together, the inseparable Sharon and Andi, spending the night, playing house, creating their own world where everything was exactly as they wanted.

And as they drove off to nowhere, to a new life, on the expressway, under the viaduct, passing the projects, the baseball stadium, heading their way toward the traffic of downtown life, they remained silent, listened to the hum of the engine. For Gabriel, it wasn’t the silence of enabling her oppressor; it wasn’t the silence of hiding her past. It was her peace for having finally accepted herself, along with all of the pain, and not feeling the hurt. The next morning, she didn’t know which name she’d use, but she knew that someone died that night, not Jack, but someone inside of her. But it was also a rebirth. And so she drove.

|

Janet Kuypers Bio

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006. |

![]()

Gabriel stopped hearing his voice when she heard that name. She had heard Luccio over and over again in the news, but Jack. She didn’t expect this. Not now. It had been so long since she heard that name.

Gabriel stopped hearing his voice when she heard that name. She had heard Luccio over and over again in the news, but Jack. She didn’t expect this. Not now. It had been so long since she heard that name.  At the restaurant, they sat on the upper level, near one of the large Roman columns decorated with ivy. She kept looking around one of the columns, because a man three tables away looked like Jack. It wasn’t, but she still had to stare.

At the restaurant, they sat on the upper level, near one of the large Roman columns decorated with ivy. She kept looking around one of the columns, because a man three tables away looked like Jack. It wasn’t, but she still had to stare.