welcome to volume 111 (October 2012) of

down in the dirt

![]()

(Cover image by Eleanor Leonne Bennett)

internet issn 1554-9666

(for the print issn 1554-9623)

Janet K., Editor

http://scars.tv.dirt

Note that any artwork that appears in Down in the Dirt will appear in black and white in the print edition of Down in the Dirt magazine.

|

Order this issue from our printer as an ISSN# paperback book: |

![]()

I’m nothing if not magnanimousFritz Hamilton

I’m nothing if not magnanimous!

She misuses her power to tell me I’m being evicted.

Bravely, I go back & tell the manager I’m so SO sorry/ I

She incinerates my drawings, crushes my nose, & the dog eats

She gives me the Cub Scout wolf badge for magnanimity, & I

I go to my mirror & see I’m a cow/ I !

|

Why use Newt,

Fritz Hamilton |

![]()

DriftLiam Spencer

The blinds allow some light to

Birds announce impending consciousness

Their torture awaits

Maybe I have nothing

|

![]()

I Feel It When I’m WholeBrian Looney

Because the good is a burden, a weight, a hassle.

Because I’ll befriend a vice before a virtue.

Appreciation is a gift.

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads the Brian Looney October 2012 (v111) Down in the Dirt magazine poem I Feel It When I’m Whole |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this poem straight from the October 2012 issue (v111) of Down in the Dirt magazine, live 10/10/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery open mic in Chicago) |

![]()

NunEric Burbridge

Mitchell West saw the rage in Sister Cletus’ eyes. She stormed down the narrow aisle. Every step she took his heart skipped a beat. His classmates leaned to avoid being brushed by her Holy habit. The heat and humidity swirled in the room of thirty students. They said if you touched a nun or the habit that meant damnation. If they touched or hit you, that was fine. The smell of starchy mildew circulated around her with every rotation of the overhead fan. She towered over him and grinned, a sinister grin that fed off the fear of a terrorized chubby freskle faced kid. Her glassy bloodshot blue eyes bulged in their sockets next to her crooked broken nose. She unfolded her arms, pushed up her sleeve and revealed the brown spots that dotted her wrinkled pale skin. “I told you to shut up, Mr. West!” Her razor thin lips trembled with anger and exposed the tips of her pointed rat-like teeth.

“Mr. West...Mr. West. Are you alright?”

|

![]()

The Pork BeltDenny E. Marshall

Old MacDonald has a farm

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads the Denny E. Marshall October 2012 (v111) Down in the Dirt magazine poem the Pork Belt |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this poem straight from the October 2012 issue (v111) of Down in the Dirt magazine, live 10/24/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery open mic in Chicago) |

![]()

the Life of a CowJohn Ragusa

Nigel Kipling woke up one morning to find himself transformed into a cow.

|

![]()

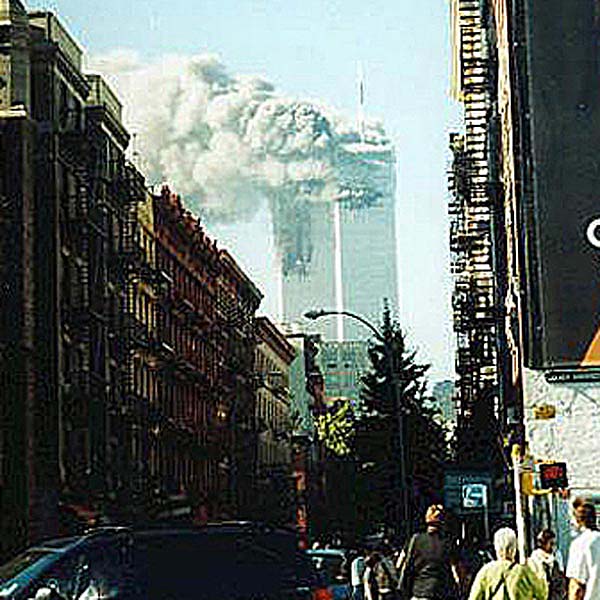

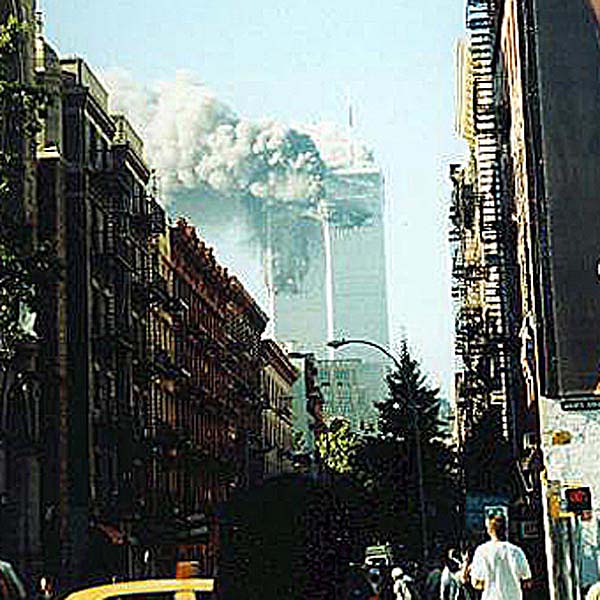

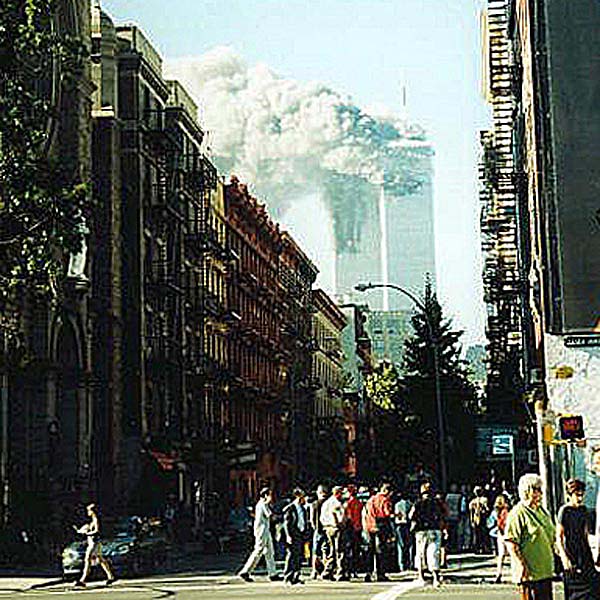

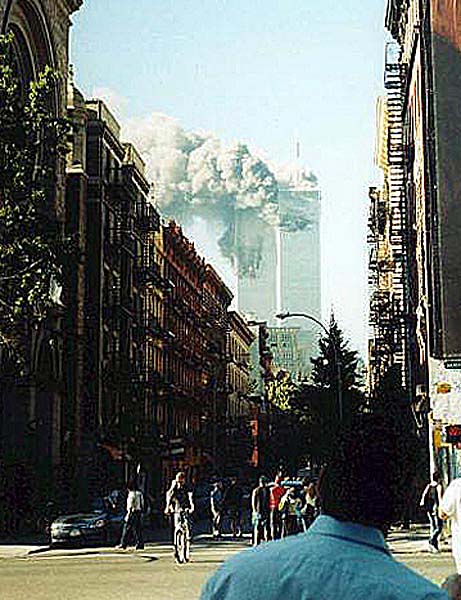

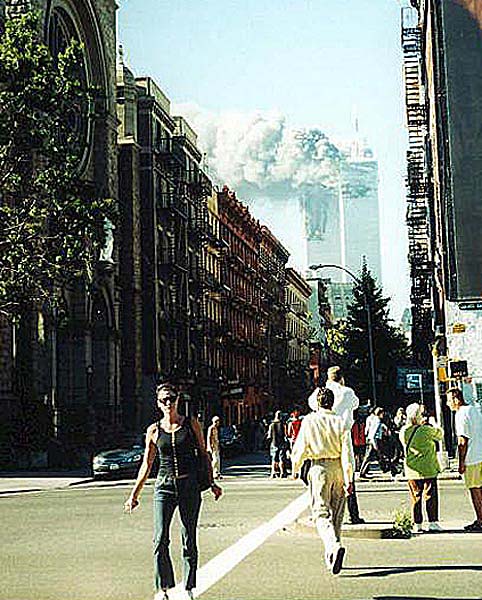

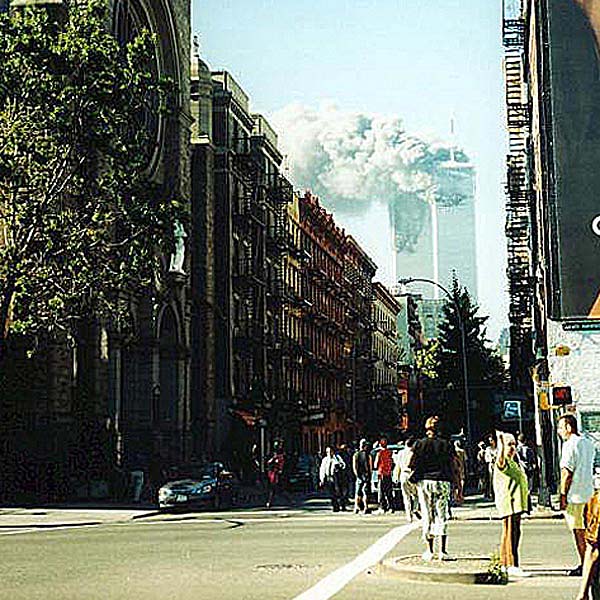

9/11 in ManhattanZach Murphy

“A plane just flew into one of the twin towers!” Kelly exclaimed. She had just opened the door to the apartment after having walked our dog Henry.

|

![]()

The ChemistNathan Hahs

My parents divorced when I was fifteen and I did not handle this well. I carried the stress in my neck and shoulders and, after a few months, I had pain all of my waking hours. My mom took me to the doctor, who gave me flexeril. I had this muscle relaxer for a couple of years before stopping. It eased the pain and put me to sleep. I was ever so grateful for the sleep, as I had always struggled with this.

|

![]()

The Papal Groping ChairBill Wolak

During the Tenth Century,

|

|

John reads the Bill Wolak October 2012 (v111) Down in the Dirt magazine poem The Papal Groping Chair |

See YouTube video of John reading this poem straight from the October 2012 issue (v111) of Down in the Dirt magazine, live 10/10/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery open mic in Chicago) |

![]()

The Bridge Over Charles RiverMegan Willoughby

I am free.

And I saw the face. After seeing the most beautiful thing I had ever witnessed, here was this face lurching out at me. She was utterly terrified. Children should never know that they are going to die. She had the face of an eighty year old man and she had hardly lived her life. I remember a book I had read: The Horror was reflected in her face. She was nightmarish.

|

![]()

Waking UpJon Brunette

My eyes opened and my hands twitched like lightning had jabbed me. As I touched the box in which I usually slept, I felt as though I was lying in the dark of night, and didn’t want to get up yet. I couldn’t move, however I tried, and my throat scratched like sandpaper. I drank a lot of liquor, like everyone did out in the West, in the early 1880s, and I never realized what could happen to me in that kind of stupor. Occasionally, the black would wrap me up like an old ratty blanket and my teeth would chatter as loudly as my heart could beat.

|

Jon Brunette BioJon Brunette went to high school in Mound Westonka High School, in Mound, Minnesota, but never graduated. Mental health problems, Schizo-Affective Disorder, limited his time in school. Still, his work has appeared in print and online. His work has appeared in “The Storyteller” (editor Regina Williams), in their October-November-December 2008 issue, and their January-February-March 2010 issue. Also, he has appeared in “MicroHorror.com” (editor Nathan Rosen), from February 2009 and into March of 2012. And, of course, he has appeared in “Down In The Dirt” (editor Alex Rand at first, a second editor has accepted others), from 2009 and into early 2012. His name has appeared in “Alfred Hitchcock Mysery Magazine” as Honorable Mention to their “Mysterious Photograph Contest”--his name appeared but not his work. His is trying to write a mystery novel to submit to an editor/agent/publisher in 2013.

|

![]()

Caskets surface in fields and marshlandMark Vogel

Jazz man Charlie Hunter wryly smiles,

Now queued, so many already escape

For god sakes, thirty four miles away,

As matter of fact the chocolate water

accepting without judgment nameless

|

Mark Vogel bioMark Vogel has published short stories in Cities and Roads, Knight Literary Journal, Whimperbang, SN Review, and Our Stories. Poetry has appeared in Poetry Midwest, English Journal, Cape Rock, Dark Sky, Cold Mountain Review, Broken Bridge Review and other journals. He is currently Professor of English at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina.

|

![]()

FirefliesKristen Forbes

My dad asks where I want to go for my birthday and it’s a joke because the only options are Pizza Hut, McDonalds or that one Chinese place a few doors down from my grandma’s hairdresser.

“So what’ll it be?” my dad asks now and I say let’s go for Chinese and he pulls the menu out of a drawer in the kitchen and grabs his reading glasses from his pocket.

and I am seven again, with my mom’s hand on my wrist; she is kneeling into me and I smell lilacs. She just set a cake on the table – not homemade like the ones Sarah’s mom made for her birthdays, but a chocolate cake loaded with pink and purple flowers she’d picked up from Costco earlier that morning. “How does it feel to be seven?” she asked and I shrugged and said it felt exactly the same as six.

“I don’t feel a day older,” I say now, peeling the wrapper off my straw and taking a sip of sweet tea.

“She listens to you more than anyone, don’t ask me why,” my dad said six months ago as we carried cups of coffee and walked across campus. I’d be graduating soon and this was one of his final visits to school. “Why don’t you just go for the summer and get her to at least consider it?” he asked, before waving at this guy named Kyle, who was walking in the other direction, toward the gym. Kyle gave a tiny wave back, then turned his head toward the sidewalk as he continued to walk. My dad loved interacting with students, going to the library and bookstore, even eating in the cafeteria. Maybe he wished he was still here, and not a pharmacist.

“It’s been fun here,” I say to Grandma now, and think how much I’ve failed. There were so many opportunities, so many chances to say, “Hey, would you ever consider moving and being closer to Dad?” But I chickened out every time, instead spending my days watching Murder She Wrote and doing crossword puzzles with her.

a few months before my mother barreled into my room after a quick, light knock on my bedroom door.

The honey chicken is crispy and greasy and sweet and I think I’ve gained five pounds in the three months I’ve been here.

“What do you mean, you’re leaving Dad?” I had asked, and she leaned across the bed to push a strand of hair that was falling in my face behind my ear.

“What are you doing out here?” Joe asks, now standing in front of the back door. He makes his way down the porch steps and I point toward the sky.

“You’re splitting us up?” I asked my mother as she looked at me, expectantly.

“Melanie,” my dad repeats, and he gets out of his chair and stands next to me at the fridge, rubbing his hands on my shoulders. I squeeze my eyes shut, suck my tears back inside of me, and reach for the orange juice.

|

Kristen Forbes BioKristen Forbes is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon whose work has been published in Wavelength Magazine, Aspens Magazine, Stork Magazine, Portland Tribune, Beaverton Valley Times, Lake Oswego Review, West Linn Tidings, Pause: Journal of Dramatic Writing, the Stand Up To Cancer website, and other publications. She holds a BFA in writing, literature and publishing from Emerson College and an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University.

|

![]()

Ricky’s SicknessMichael Cavazos

Guadalupe hit the on switch, and a strong bopping beat roared from her speakers. The party was on. Everybody was having a good time. Fools played beer pong. Fellas took shots, getting some fire in their bellies. Females stared the others down, their eyes packed with bullets. Couples grinded on the living room floor assured that they were going to get lucky tonight.

|

![]()

At First GlanceBob Strother

Bernice Crowder was slumped in her wheelchair, dozing, when the squeak, squeak, squeak of rubber soles on linoleum awakened her. She checked the screen of the muted television where Vanna White illuminated letter tiles and smiled brightly for the cameras. Must be dinnertime, Bernice thought.

She was fifty-two when it happened, driving home from the drugstore after replenishing her supply of over-the-counter antihistamines. She’d taken the cut-through street, the one she always used to avoid the main thoroughfare’s traffic lights, and was deciding on what to cook for dinner when she spotted the yellow vase. It sat alongside the road among some flattened cardboard boxes and other assorted rubbish obviously meant for trash pickup. Such a lovely color, she thought as she passed by. It would look perfect on the dining room table with some tulips from the garden. On impulse, she circled the block and came back around, slower this time, and eased to a stop just beyond the uneven heap of boxes. She hesitated for a moment, embarrassed at the thought of rummaging through someone else’s castoffs. What if someone saw her? Then she thought, Rubbish! I’ll only be a minute, and chuckled at her joke.

The two responding police officers—one black with Sergeant’s stripes on his sleeve, the other a younger white man with none—asked Bernice to show them the scene of the abduction. She did so, pulling onto the shoulder where she had first seen the vase as the patrol unit nosed in behind her. The two officers got out of their car and joined Bernice at the edge of the road.

“Mrs. Crowder, I have your dinner. Shall I put it on your tray?”

|

![]()

AugustDon ThompsonEveryone here tends toward ghostliness by the end of summer. Irritable, enervated, worn so thin we see through each other. Old arguments come back to haunt us in August. Women’s voices scrape like knives on a whetstone, honing for a fight. Men won’t talk at all; their lizard eyes glare out from under a silence too hot to touch. If an evening breeze stirs at all, it blows hard from the wrong direction. Grit gets in your teeth, and its so dry you’d swear it originated in an ancient ossuary. Balm has nothing to do with it. After dark, the sirens—hopefully in the distance, fading. But you hear the spectral wail down the street, the lamentations next door, the banshee in your attic. At least the blood cries out from the sidewalk with a voice only God can hear. Maybe this August won’t be like that. I think the seminars will be good for us and those weekends at the retreat center among the high pines. Up there the air is too thin to hold a grudge. Already I feel anger flicker to the end of its neurons and burn out. And the lovely blue enzymes of peace seeping into my mind. I think everything will be all right... Easy to say at the end of April.

|

![]()

Plight of TrothChristopher Reinhardt Krueger

When he stopped showing up, Colin’s boss called his phone but it was off. His friends called too and, unable to reach him, assumed he had finally cut loose and they were happy for him. The neighbors had hardly known him. He hardly spoke to his mother and his father was dead. Colin Myers had disappeared and for a long time very few people noticed and hardly anyone seemed to care.

Neither Colin nor Sierra moved with much and their apartment was sparsely furnished. In the bedroom: just a full size mattress on the floor and some collapsible fabric cabinets in which clothes were sorted but left unfolded. The living room: a big maroon couch, an old gray tube TV with a bunny ear antenna, and a wood and cinder block bookshelf on which a boombox sat. There was hardly anything in the basement: a washer and dryer, some spray painted pictures on the exposed brick walls, and an old chest freezer set in the shadow beneath the stairs. The space was illuminated by a single dangling bulb which could be turned on only by a frayed, dangling cord.

After having heard nothing from her son for nearly a year, Diane began to worry. She tried calling him many times but the phone was never on. She left voicemails until the box was full but the calls were never returned. She called what friends’ phone numbers she had, but either the numbers had been changed or they too hadn’t heard from him. She called the family members to whom she thought he might have reached out. Not the slightest whisper anywhere. The man handed Diane the slip of paper with an address on it. He said he would prefer if she didn’t say where she got it. He closed the door without saying goodbye.

A few hours later Sierra opened her front door until the chain caught and peered through the gap. “Mrs. Myers,” she said, her head shaking once with surprise, “what are you doing here?”

At the top of the stairs Diane tried the switch but nothing happened. The light from the living room illuminated the walls halfway down into the basement and Diane held the banister as she walked down the creaking stairs. At the bottom she slid her feet across the cement floor to make sure there were no more steps.

Diane went into the kitchen and Sierra invited her to sit. Sierra stood at the sink washing dishes with her back to the room. On the counter there was a long strip of used plastic wrap and on the table there was a plastic bowl and a spotted silver spoon. Diane thanked Sierra for the food and sat down.

At the bottom of the stairs, Diane picked up the two boxes with papers and CDs and when she started up the stairs she saw again the shape in the corner. She set the boxes on a stair and walked around to the front of the freezer.

|

![]()

i believe i’m done with this. the proverbial towel.Gary Lundy

blood gushes in predictable fashion in every direction.

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads the Gary Lundy October 2012 (v111) Down in the Dirt magazine poem i believe i’m done with this. the proverbial towel. |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading this poem straight from the October 2012 issue (v111) of Down in the Dirt magazine, live 10/10/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery open mic in Chicago) |

![]()

The Black MirrorLasher Lane

After donning only black for almost a decade as the honorable wife who’d long surpassed Italian-Catholic mourning etiquette, my grandmother had finally given up the label of third wheel-slash-lonely widow. She had remarried, this time to an eccentric German man named Gerhard. Not only did he inherit her extremely loud snoring, which we were all thankful for, but she inherited his horsehair mattress, which he refused to part with, and she admitted took some getting used to because it was so lumpy it felt like the horse was still in it. She also acquired his massive relic of a house on the corner of 87th street in North Bergen, a town that was home to two Revolutionary War sites: The Battle of Bull’s Ferry and the Three Pigeons Inn.

Nothing had happened on our second attempt, but that didn’t mean I was about to give up. While everyone around me, including Will, was becoming obsessed with this new group from England, the Beatles, I was becoming obsessed with this strange devotion I’d discovered. I even went so far as to sneak one of the books home with me on certain weekends. It became all I thought about, this weird “religion” that believed we all were born from the Sun and died from the Moon, that we were aided by Planetary Angels, that all the souls that would ever be created resided in mansions since the beginning of time, eternally recycled yet infinitely connected toone another, each sharing a sixth sense, that Silver Cords were attached to our physical bodies and only in death would these cords be severed. And that by looking in a mirror we could see another time. Not only did I start imagining everyone I saw walking around like marionettes attached to the Heavens by strings, but I also wondered who I might have been a hundred years ago and if the mirror would ever show me. I even began meditating daily as the book suggested.

|

![]()

FirefliesCassia Gaden Gilmartin

The hem of my dress is torn by the time the music stops. I don’t know how the yellow stain got there, or how my tights managed to tear like a ravine opening and leave the skin of one knee exposed. The disco lights flicker out and the main light turns on. I shut my eyes against it. When I open them, I know my friends will be smiling at me – faces caked with make-up, deathly pale underneath, like painted ghosts. I know I’ll have to smile back.

|

![]()

medicineJanet Kuypers(1994)

A few years ago, I felt so much pain in my joints that I couldn’t walk or pick up a carton of milk in the morning. At age 21, I limped and ached; my right ankle, left knee, and right hand were swollen. I was also sore in my back and shoulders. I cried in pain daily.

A friend and co-worker was recently hospitalized with an ulcer. When she came back, the pain still remained–especially during menstruation. She always had severe menstrual cramps, and with the ulcer present there would be days at the office when she would have to lay down underneath her desk until the pain went away.

My grandmother was a feisty and strong woman in her mid-eighties. Her bowling average hovered around 176. She lived alone in a condominium. Our family had dinner together weekly with her.

I told friends about my grandmother’s experience with the doctors. More than one person mentioned that my grandmother’s next of kin could probably win a lawsuit against the doctor who misdiagnosed her, especially when she complained to us when she was alive that he didn’t listen to her. But the problem was deeper than that.

|

GuiltJanet Kuypers(Summer 1994) I was walking down the street one evening, it was about 10:30, I was walking from my office to my car. I had to cross over the river to get to it, and I noticed a homeless man leaning against the railing, not looking over, but looking toward the sidewalk, holding a plastic cup in his hand. A 32-ounce cup, one of the ones you get at Taco Bell across the river. Plastic. Refillable. Normally I don’t donate anything to homeless people, because usually they just spend the money on alcohol or cigarettes or cocaine or something, and I don’t want to help them with their habit. Besides, even if they do use my money for good food, my giving them money will only help them for a few hours, and I’d have to keep giving them money all of their life in order for them to survive. Once you’ve given money, donated something to them, then you’re bound to them, in a way, and you want to see that they’ll turn out okay. Besides, he should be working for a living, like me, leaving my office in the middle of the night, and not out asking for hand outs. I’m getting off the subject here... Oh, yes, I was walking along the sidewalk on the side of the bridge, and the homeless man was there, you see, they know to stand on the sidewalks on the bridge because once you start walking on the bridge you have to walk up to them, and the entire time you’re made to feel guilty for having money and not giving them any. They even have some sort of set-up where certain people work certain bridges. Well, wait, I’m doing it again... Well, I was walking there, but it wasn’t like I was going to lunch, which is the time I normally see this homeless man, because during lunch there is lots of light and lots of people around and lots of cars driving by and I’m not alone and I have somewhere to go and I don’t have the time to stop my conversation and think about him. Well, anyway, I was walking toward him, step by step getting closer, and it was so dark and there were these spotlights that seemed to just beat down on me while I was walking. I felt like the whole world was watching me, but there was no one else around, no one except for that homeless man. And I got this really strange feeling, kind of in the pit of my stomach, and my knees were feeling a little weak, like every time I was bending my leg to take a step my knee would just give out and I might fall right there, on the sidewalk. I even started to feel a little dizzy while I was on the bridge, so I figured the best thing I could do was just get across the bridge as soon as possible. I figured it had to be being on the bridge that made me feel that way, for I get a bit queasy when I’m near water. I don’t usually have that problem during lunch when I walk over the bridge and back again, but I figured that since I was alone I was able to think about all that water. With my knees feeling the way they were I was afraid I was going to fall into the water, so I had to get myself together and just march right across the bridge, head locked forward, looking at nothing around the sidewalk, nothing on the sidewalk, until I got to the other side. And when I crossed, the light-headed feeling just kind of went away, and I still felt funny, but I felt better. I thought that was the funniest thing.

|

Watch the YouTube video Published in her book Close Cover Before Striking, read (for future audio CD release) live at Striking with Nature and Humanity at Trunk Fest , in an outdoor Evanston IL feature 06/25/11 |

See the full YouTube video of Striking with Nature and Humanity at Trunk Fest, live 06/25/11, with this writing |

Watch the YouTube video of Kuypers reading this poem at the open mike 3/14/12 at Gallery Cabaret’s the Café Gallery in Chicago, from the Kodak |

Janet Kuypers Bio

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006. |

![]()

“What?” I uttered.

“What?” I uttered. That was news to us. We followed him into our apartment building like zombies. It was time to turn on the television. We were freaking out. What if more planes are headed to New York? What if one of our planes shoots one down, and it crash lands on Manhattan and kills us? Those thoughts were running through my mind.

That was news to us. We followed him into our apartment building like zombies. It was time to turn on the television. We were freaking out. What if more planes are headed to New York? What if one of our planes shoots one down, and it crash lands on Manhattan and kills us? Those thoughts were running through my mind. Kelly was really pissed off. She thought it was a terrible idea to open the bookstore the day after 9/11. I understood why she felt that way. You’re living on a small island, and the day after thousands of people were murdered on that island, you’re going back to business as usual. In fairness, Lynn and Doug, the owners of the store, opened it seven days a week. They probably reopened it out of habit. I was concerned about the fires that were raging fairly close to my home. In retrospect, it was very unlikely that the fires would be allowed to spread that far. At the time, though, I was still a little shell-shocked. I was thinking, okay, I’ll go to work. However, if I need to leave, to help Kelly evacuate, I won’t hesitate.

Kelly was really pissed off. She thought it was a terrible idea to open the bookstore the day after 9/11. I understood why she felt that way. You’re living on a small island, and the day after thousands of people were murdered on that island, you’re going back to business as usual. In fairness, Lynn and Doug, the owners of the store, opened it seven days a week. They probably reopened it out of habit. I was concerned about the fires that were raging fairly close to my home. In retrospect, it was very unlikely that the fires would be allowed to spread that far. At the time, though, I was still a little shell-shocked. I was thinking, okay, I’ll go to work. However, if I need to leave, to help Kelly evacuate, I won’t hesitate. “Okay,” he said, while snapping another photo.

“Okay,” he said, while snapping another photo.