Testament

cc&d magazine

v256, July/August 2015

Internet ISSN 1555-1555, print ISSN 1068-5154

Note that in the print edition of cc&d magazine, all artwork within the pages of the book appear in black and white.

Order this issue from our printer

as a perfect-bound paperback book

(6" x 9") with a cc&d ISSN#

and an ISBN# online, w/ b&w pages

Testament

|

poetry

the passionate stuff

|

Mental Nervous

Sheryl L. Nelms

with a diagnosis

of schizophrenia

all circuit boards

are blown

brain storms

stir his

emotions

swirl

stray

thoughts

into

scrambled

eggs

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

From Smoke

Maura Gage Cavell

Smoke blocks all vision.

Escaping to the outdoor gold of sun,

a shining glare,

my eyes burn; an opaque

fuzzy view. A sudden snake

slithers through the gate,

its splitting shell of skin

trails white and black patterns

as it goes far beyond

the edge of the yard.

What smoke-escape brought

me here? Why am I alone

in this heard of paradise pinks

and vibrant violets?

New grass pushes forth

through earth, a spring

of light spectrums,

soft rain, a bright dream-

scape. A rainbow arches overhead,

wraps around this town.

|

Maura Gage Cavell bio

Maura Gage Cavell is Professor of English and Director of the Honors Program at Louisiana State University Eunice. She resides in Crowley with her family. She has recently published poetry in California Quarterly, Poem, Louisiana Literature, Boulevard, and The Louisiana Review.

|

December Eleventh and Onward

Jesse Williams

In 100 years

there will have been

enough terrible events

that must never be forgotten

to reduce all flagpoles permanently

by half.

|

Strong Wind in the Mountains

Xanadu (Ofmickiewiczfame)

Landscape bows for both sun and wind

to haunt clouds and through rays of light

towards the western side there

they are moving like haze,

Their cumuli drifting downwards

to cover natural black of cliff riffs

escaping from pale moonlight and that’s

all what’s left right now from this song.

(Thanks to Stanislaw Witkiewics his 1895 Wiatr Halny

in Sukiennice Muzeum Krakow and Miles Davis)

|

Cosmic Consciousness

Dr. (Ms.) Michael S. Whitt

Cosmic consciousness means one has feelings of relatedness with all that exists

Within the multiverse and all its components

Multi is superior as a prefix than uni to image this large system of which we’re parts

The latter implies a homogeneity which doesn’t exist

The system’s complexity with so many dimensions and connections belies any such uniformity

Cosmic consciousness is uniquely powerful in several ways

Among them: Intensity, Depth, & Creative Inspiration

As one enters cosmic consciousness, a feeling of expansiveness pervades their being

A sense of being a vast, inclusive being

These seem related to a novel feature of cosmic consciousness

It involves the breakdown of socially conditioned barriers which divide the conscious ego

From the far larger and wiser ‘off-conscious’ Self

One is vaguely aware of the latter until it comes over the threshold to waking consciousness.

If one is mentally healthy, the emergence into full consciousness of these brings joy and delight

There are dangers in opening the ‘off-conscious’ Self of those who have repressed and denied experiences to the point they’re lost to awareness

Without therapy such persons won’t reach the heights of cosmic consciousness on a psychedelic substance, but will descend to the depths of hell; they’ll have a bad trip

Cosmic consciousness may be achieved through ingesting psychedelic substances, immersing in ‘Big Nature,’ meditation or a combination of two or all three

When one has positive experiences on psychedelic substances like LSD, synthetic Mescaline, and Psilocybin (gold capped) Mushrooms

One often discovers with joy and delight that the deepening and expansion of perception and other transformations which happened while tripping

Are permanent and positive changes to which one has access after the trip

Called ‘Flashbacks,’ many of narrow minds see these as harmful and negative

This is the case only with repressed persons

A flashback to healthy person can be

Anything from a snow covered mountain peak to a rose garden to an excellent sexual experience, to a crystal clear spring, and much more

|

Sanctuary

Chris Roe

Shafts of light

Through cathedral windows.

Dappled shade

Upon the leaves

Beneath my feet.

Bird song

In the branches above.

In the distance

Hind and fawn

Cross the forest track.

The sweet fragrance of autumn

Fills the misty air.

A gentle breeze

Moving colours

To the forest floor.

So precious

Such beauty,

So hard to find

Such peaceful sanctuary.

|

Possum Slim (V2)

Michael Lee Johnson

105 years old today

Possum Slim finally

gets his GED,

drinks gin,

talks with the dead.

“Strange kind of folks

come around here,

strange ghosts”

he says, “come

creeping pretty regular.

Just 2 ghosts,

the only women I ever loved,

the only women I ever shot dead.”

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

won’t settle down

Linda M. Crate

my mother told me once

that all anyone wants

is for me to

settle down,

but what if i don’t want to?

even if i’m married

i imagine i’ll be a wild thing

my children

will never know when i’m going to

be their mother or when i’ll be a wild bird

i’ll be responsible, surely,

but i’m going

to live life on my terms not the other way

around;

people don’t get to dictate my future

i do—

gypsy hearted free spirit

i will dance,

and my children will dance with me not knowing

the harm of conformity because i will let them

dream as i was never allowed to,

but i rebelled because

i had to;

my heart would not be caged

or restrained

my dreams insisted on dancing with unicorns,

clouds, mermaids, faeries, vampyres, satyrs, nymphs,

and fauns—

my husband will be a wild thing, too,

and no one will be able to tame us and the world

will be our crayon and we won’t

color in the lines.

|

scarred<>

Linda M. Crate

there’s no end to the scars

leading down

all the entrails of what’s left of

my heart,

it’s been torn to pieces so many

times i can no longer

keep count;

there’s no need to

because to live is to suffer

we weren’t all born with golden spoons

in our mouths and even those

with money have issues

of their own

we’re all flawed creatures

seeking to deflate one another in our pursuit

of perfection which can never be

found—

the neighbors downstairs slam doors

and yell to cut across the oceans of their agony,

i drown and numb myself with my

addiction of music and like an addict if i don’t

get my daily dose

i rage and snarl and become unbearable;

get headaches and feel miserable

i was once told scars

were beautiful

because they burned us with the searing past

that failed to kill us,

but sometimes i think death would be a reprieve

rather than reliving all these tears day and day again

every day is exactly the same

i need it to change,

but i don’t know how.

|

as a razor

Andy Roberts

buddy rich in nursing home

big swing face man from planet jazz

all knobby knuckles eyes in skull

can’t shake hands sips coffee through a straw

know what chaps my ass says budd

fuckin muzak eyes to ceiling speaker

all day long you getting out of here

gonna play again play i can’t

hold a fucking pencil what can i do

for you buddy eyes peek out

all i wanna do is feel sharp

he says one more time

|

Andy Roberts Bio

Andy Roberts lives in Columbus, Ohio where he handles finances for disabled veterans. His work has appeared in hundreds of small press and literary journals. Many Pushcart nominations but no wins. His latest collection of poems, Pencil Pusher, is due out in March from Night Ballet Press.

|

All In

G. A. Scheinoha

He laid his life, wife, family;

everything he owns on the altar

of her arms. She consumed

that sacrifice with

a benign smile.

Though totally burned out,

he never felt more alive

than when licked by

the flames of the flesh.

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

untitled (the only)

DG Mago

Craving for touch

Affection of any kind

Unfamiliar with anything healthy

Too familiar with the circles of pain and disappointment

The only touch she had was from a closed hand slapping her face

Pretending it was a gentle stroke caressing her cheek

The only touch she had was by a fiendish relative

Grooming her for his own twisted enjoyment

Betraying her trust

She no longer trusts herself

The only touch she had was by a cigarette butt burning her skin

Burning into her psyche

Scaring deeply

The only warmth she felt was from the ashes

Crumbling to the ground along with her self-worth

The only warmth she felt was from soiled sheets and blankets

Which became her shield of protection

Against constant bickering

And unforgiving caretakers

The only warmth she felt was from scalding hot water

That filled the bathtub

Thrown in and held down against her will

Learning not to scream

Not to cry

Keeping the pain within

A pattern she repeats

Leading to her self-mutilation

And self-destructive habits and choices

That is why she runs

When she sits in front of a warm fire

And basks in the heat

Its mesmerizing glow

Although appealing

It’s unfamiliar

Uncomfortable

Terrifying

So she looks for the hot coals

And reaches too close

Time after time

Because of the familiarity

Because it’s all she knows

|

DG Mago bio

DG Mago was born and raised in NYC. He has a Masters degree in counseling and has worked in the prison system with incarcerated youth dealing with serious crimes, substance abuse, and sexual and physical abuse. He relocated and lived in the Central American country of Nicaragua for 4 years. While in Nicaragua, he started a program to help at risk children to avoid some of life’s pitfalls. Since DG Mago became involved in organic agriculture and bringing clean drinking water to rural communities, he bought an organic coffee farm (fincajava.com). His writing is unique and fresh, and his poetry is thought provoking and moving. He has written and self-published two books, Shelterball and Flurries, both including original poetry. He is looking for a publisher and literary agency to represent him and eventually use their connections to help turn his vision into a film, mini-series or play.

|

Plovers

Donald Gaither

not yet airborne

plover chicks dash thru the weeds

like mice on stilts

|

Convoluted_Afternoon, art by Brian Looney

Buzzing in Limbo

Preston R. P.

That house had been my home for three years. The kitchen was grounded with chipped tile, piss colored grout and wine stains on the marble counter. I got it as a gift from my brother--the one who spent his days sprawled on a yellow mattress, soaked in his own filth, while trying to ignite cigarets with a broken lightbulb. These days he's fucking around in Arizona, probably doing the same thing.

The popcorn ceiling snowed paint chips that fell in your drink anytime you walked under a wrong spot, or the rusted ceiling fan went over the 3rd speed.

The outdated wall paper, the hissing toilet, the generic shower curtain that draped over a tub where the drain accumulated a ring of grime--

I walked into the living room and unveiled the heavy drapes where the sun radiated in the battlefield of orange peels, punctuated by beer cans and broken mirrors.

Cockroaches made their home inside of used condoms, nesting in ejaculate.

The TV was still cascading with static from the nights

I

Just sat

and

watched it.

|

Preston R. P. brief bio

Preston R. P. is a writer and artist from Florida. He believes that art is essential to humanity. He has worked with many artistic mediums. Recently, guitar and drawing have given way to poetry and short stories.

|

ATONEMENT

Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal

I take off my skin for you.

I crawl on the wild grass too.

I become less than naked.

I run my tongue through fire.

I tie my tongue in a knot.

I burn off all my hair.

I pour whiskey in the burns.

I paper cut my heart for you.

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

Testament

Oz Hardwick

This is the truth. Not the whole truth-

that would be a lie. There is no whole truth,

just piecemeal insights and epiphanies, scratched

from parks and alleys, from vacant lots,

from schoolyard walls and subway shadows.

But this is the place where the pieces fit,

where my truth, your truth, the truths of strangers

flash and fuse to a bright whole,

a shining mosaic, a stained-glass icon,

a votive light of pure faith.

And in this light, this truth, nobody will kneel,

nobody will bow their head, nobody

will apologise, nobody will beg forgiveness

for being alive. Instead, we’ll testify

to our shared selves, our shared truth,

to our shared pain, our shared love,

the blood pumping through our shared heart,

and our shared, messed-up, beautiful humanity,

aloud in our unique shared voices,

for ever and ever. This is the truth.

|

They murder guys in Knoxville

Fritz Hamilton

They murder guys in Knoxville &

dump them in the river/ by the

time they’re found ten miles away

they’re bloated beyond recognition &

they stink/ they make a movie about

them seen the world over &

make them heros/ the town has

never made so much money over

two celebrity corpses. The movie

is shown to a full house everynight, &

everybody makes money over the

dead/ those who never knew them claim

they were their friends/ in a month the

movie’s gone & nobody seems to

care/ the salad days are done &

the lettuce rotten/ everybody’s

back to eating Big Macs &

not even Big Mac knows why

|

They’re cutting off heads again in Libya

Fritz Hamilton

They’re cutting off heads again in Libya

/ soon they’ll box one like a cake &

send it here/ I’ll nail it on a Muslim’s

neck & send it back/ it’s Fritz’s jihad to

show that I too am a man of principle/ if

I were truly into it, I’d send them my

head/ they’ll get it anyway in time/ they

can slather it with good frosting &

eat it on my birthday, which

hasn’t been celebrated for years, aside

from books from my mother &

children/ I prefer that to

receiving their heads, but

heads might be a new trend as

anything loving is out of the

picture, &

why accept a picture of a head when

I can get the real thing/ a

vacation to Libya just wouldn’t

be enough/ perhaps they’d accept my

body & send my head back to L.A., & if

it’s the right season, maybe

it’ll get an Oscar . . .

|

Fisherman’s Son

John Grey

You can’t get the dying fish out of your head,

how hard and uselessly it breathed,

the thrashing of its tail,

whacking of its head against the ground.

And the big eye looking up at you

even as your father gripped its gray body,

fingers working like a weaver’s

to remove the hook.

It was not the fish’s world, that’s for sure.

Nor yours either as you sat there,

ordered not to say a word

nor make a sound

when the line was cast

and even dumber

in your father’s triumph.

And then the stillness of the creature

laid out on the bank with three others,

a choir of death

that only you heard singing.

|

John Grey bio

John Grey is an Australian poet, US resident. Recently published in New Plains Review, Rockhurst Review and Spindrift with work upcoming in South Carolina Review, Gargoyle, Sanskrit and Louisiana Literature.

|

For Now

Frank C. Praeger

Cached, embattled, cradled

among fallen timber, mushrooms, trillium,

tossed out legacies,

truant to yesterday’s promises.

Today tattletales reign,

untidy,

faces dinged.

A patron, too, I do not slight,

wave off as too ephemeral.

Were elephants ever contrite?

Then, to have been tracked down by a coyote,

now, no home,

not around the corner past the fallen trees,

the rotting vegetables in the untended garden,

and that autumnal amber light,

and those missing

that once completed my life.

Should I bark, should the moon pause, tides vanish?

A loss least looked for.

No one has watched,

not even crows.

|

After Alberta’s Centennial

Ronald Charles Epstein

Provincial legistlature grounds:

the prime minister has left,

the premier is elsewhere.

A visitor is arriving,

walking through the empty grounds

after the clowns have departed.

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

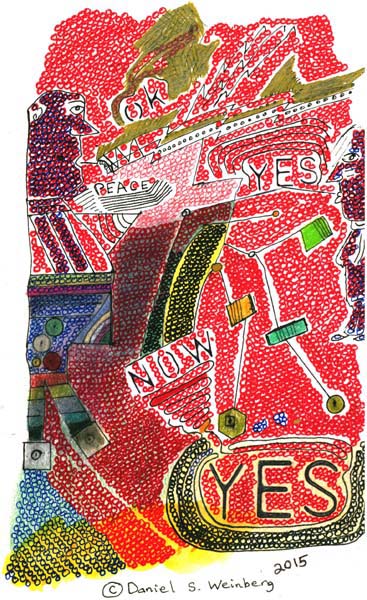

Peace Yes Now, art by Dr. Shmooz

i am reaching

Traci Lavois Thiebaud

i am reaching

across any table,

morming coffee, breakfast, lunch

for the salt,

even before the wound appears,

i am stretching

pink tongue to lick

i bought a welcome mat

for the trauma and the pain,

the knock of an old friend

of a familiar finger on the doorbell,

i take them as they come,

bite by bite and

bracing for the

china glass fall,

|

Chicago Pulse

“sweet poems, Chicago ”

|

Eight to Sixteen

Janet Kuypers

10/8/14

You came back again

from one of your trips

to the other side of the planet.

You know I love you

more than anything on Earth,

but... I’m getting used to your absence.

#

It’s a terrible thing to say, I know,

but when you came back this time

and said you had a fever

I figured you ingested their toxic water

and you’d have the stomach flu

for days, but then you’d be fine.

But this time, with your fever,

I remembered how you drank the water

swimming south of the Equator,

and I thought nothing of it.

It would clear up in a week.

I’ll just hold off on kissing you again.

#

But after eight days,

you went to the doctor,

told them of your travel and ails.

And that’s when the doctor

called the CDC

and the Federal agencies swarmed in.

After you left for the doctor,

the next contact I had

was with men in Hazmat suits at my door.

They asked me if I was alone.

They asked me if I had any children.

Then they asked me to come with them.

I told them I needed to wait

for my husband, and they told me

you were now in isolation.

After hours, they told me

that you caught a nasty virus

while you were away on your trip —

But I said, “Wait a minute,

he was on a work trip, and his company

made him take a ton of drugs

so that he’d be immune

and wouldn’t catch anything —”

and that’s when they stopped me, right there.

They locked me in a room.

They told me I couldn’t leave.

Then they said he caught a bad strain

while helping a woman

he found on the street,

bleeding, pregnant, and in pain.

It took them two days

to discover the details

before they gave me the news.

“He’s in isolation,

we’re trying new treatments,

and hopefully he’ll be okay.”

But, I know of this virus,

it’s usually lethal,

so... Please. Let me see him. Now.

That’s when they said, “Sorry,

it’s out of our hands,

but you must be quarantined too.”

So I screamed at the medics,

all to no avail,

as they swore I had to stay safe.

So...

I paced in my isolation.

I watched the drive by news.

And I heard them say stats

that death from this virus

can come from 8, up to 16 days.

Eight to sixteen days.

It was eight days

before he even went to the doctor —

will this waiting do him in?

I couldn’t talk to him.

I couldn’t see his face.

I couldn’t kiss him, or

tell him I loved him.

That I’ll always love him.

That I’m nothing without him.

#

The morning of the 5th day,

still trapped in isolation,

that’s when they told me he died.

#

My blood work was clean,

but they kept me in isolation

when they said they’d cremate my love.

And all I could think

was, ‘after you’re done,

send him to Arlington National Cemetery’

so the world will know

he’s a hero to more than just me,

as you kept me away ‘til he died.

And still, I continue to pace,

trapped in this room, alone,

with nothing to wait for

ever again.

|

junk

Janet Kuypers

(started 10/19/14, completed 10/21/14)

We all think we’re so important

all the way down to our DNA —

but for all of our chromosomes

all of our genetics

and our glorious genome —

well, if you look at it closely,

if you look all the way down to our DNA,

you’d be stunned to see

how much

of what we’re made of

is just

junk.

Yeah,

yeah,

I know,

we’ve got so much DNA,

we’re such

complex

creatures,

but —

Think of it this way:

a simple worm

has maybe

7% junk DNA.

A fruit fly,

maybe 3%...

And then there’s us humans,

with our big brains —

and ourjunk DNA

seems to go off the charts.

What a fun phrase,

“junk DNA”,

because after

discovering the helixes

that make us

us,

we’ve found sequences

withnodiscernible function.

And we love that label,

junk DNA —

maybe it’s a sign

that we’re all hoarders at heart,

we all want more

and everything we get

has to be bigger and better,

even if we don’t know

what it’s for.

Because, I mean,

even a newt

has a genome

25 times

longer than ours...

What does that say

about what we’re made of?

Us little creatures

compared to rhinos and elephants,

using our big brains

to stay on top of the food chain

over those deadly panthers,

lions, tigers, and bears.

Look how we’ve won

with our opposable thumbs,

we help 200 species

go extinct every day.

Wow,

what warriors we are.

Species on Earth

haven’t gone extinct

like this

since the dinosaurs.

Wow.

What warriors we are.

We think we’re all so great

with our opposable thumbs

and our really big brains,

and when we look at it all,

microscopically, you know...

We become smart enough

to know our own DNA,

and we start to wonder

how smart we really are,

when we see how so much

of what we’re made of

is really

just

junk.

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers performing her poem Junk at the beginning of the evening live 10/22/14 at Chicago’s open mic the Café Gallery (C)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers performing her poem Junk at the beginning of the evening live 10/22/14 at Chicago’s open mic the Café Gallery (S)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers performing her poem Junk in the middle of the evening live 10/22/14 at Chicago’s open mic the Café Gallery (C)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers performing her poem Junk in the middle of the evening live 10/22/14 at Chicago’s open mic the Café Gallery (S)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem Junk from cc&d v256, “Testament” live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (from a Canon Power Shot)

|

See YouTube video

of Janet Kuypers reading her poem Junk from cc&d v256, “Testament” live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (filmed with a Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

|

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006.

She sang with acoustic bands “Mom’s Favorite Vase”, “Weeds and Flowers” and “the Second Axing”, and does music sampling. Kuypers is published in books, magazines and on the internet around 9,300 times for writing, and over 17,800 times for art work in her professional career, and has been profiled in such magazines as Nation and Discover U, won the award for a Poetry Ambassador and was nominated as Poet of the Year for 2006 by the International Society of Poets. She has also been highlighted on radio stations, including WEFT (90.1FM), WLUW (88.7FM), WSUM (91.7FM), WZRD (88.3FM), WLS (8900AM), the internet radio stations ArtistFirst dot com, chicagopoetry.com’s Poetry World Radio and Scars Internet Radio (SIR), and was even shortly on Q101 FM radio. She has also appeared on television for poetry in Nashville (in 1997), Chicago (in 1997), and northern Illinois (in a few appearances on the show for the Lake County Poets Society in 2006). Kuypers was also interviewed on her art work on Urbana’s WCIA channel 3 10 o’clock news.

She turned her writing into performance art on her own and with musical groups like Pointless Orchestra, 5D/5D, The DMJ Art Connection, Order From Chaos, Peter Bartels, Jake and Haystack, the Bastard Trio, and the JoAnne Pow!ers Trio, and starting in 2005 Kuypers ran a monthly iPodCast of her work, as well mixed JK Radio — an Internet radio station — into Scars Internet Radio (both radio stations on the Internet air 2005-2009). She even managed the Chaotic Radio show (an hour long Internet radio show 1.5 years, 2006-2007) through BZoO.org and chaoticarts.org. She has performed spoken word and music across the country - in the spring of 1998 she embarked on her first national poetry tour, with featured performances, among other venues, at the Albuquerque Spoken Word Festival during the National Poetry Slam; her bands have had concerts in Chicago and in Alaska; in 2003 she hosted and performed at a weekly poetry and music open mike (called Sing Your Life), and from 2002 through 2005 was a featured performance artist, doing quarterly performance art shows with readings, music and images.

Since 2010 Kuypers also hosts the Chicago poetry open mic at the Café Gallery, while also broadcasting the Cafés weekly feature podcasts (2010-2015) (and where she sometimes also performs impromptu mini-features of poetry or short stories or songs, in addition to other shows she performs live in the Chicago area).

In addition to being published with Bernadette Miller in the short story collection book Domestic Blisters, as well as in a book of poetry turned to prose with Eric Bonholtzer in the book Duality, Kuypers has had many books of her own published: Hope Chest in the Attic, The Window, Close Cover Before Striking, (woman.) (spiral bound), Autumn Reason (novel in letter form), the Average Guy’s Guide (to Feminism), Contents Under Pressure, etc., and eventually The Key To Believing (2002 650 page novel), Changing Gears (travel journals around the United States), The Other Side (European travel book), the three collection books from 2004: Oeuvre (poetry), Exaro Versus (prose) and L’arte (art), The Boss Lady’s Editorials, The Boss Lady’s Editorials (2005 Expanded Edition), Seeing Things Differently, Change/Rearrange, Death Comes in Threes, Moving Performances, Six Eleven, Live at Cafe Aloha, Dreams, Rough Mixes, The Entropy Project, The Other Side (2006 edition), Stop., Sing Your Life, the hardcover art book (with an editorial) in cc&d v165.25, the Kuypers edition of Writings to Honour & Cherish, The Kuypers Edition: Blister and Burn, S&M, cc&d v170.5, cc&d v171.5: Living in Chaos, Tick Tock, cc&d v1273.22: Silent Screams, Taking It All In, It All Comes Down, Rising to the Surface, Galapagos, Chapter 38 (v1 and volume 1), Chapter 38 (v2 and Volume 2), Chapter 38 v3, Finally: Literature for the Snotty and Elite (Volume 1, Volume 2 and part 1 of a 3 part set), A Wake-Up Call From Tradition (part 2 of a 3 part set), (recovery), Dark Matter: the mind of Janet Kuypers , Evolution, Adolph Hitler, O .J. Simpson and U.S. Politics, the one thing the government still has no control over, (tweet), Get Your Buzz On, Janet & Jean Together, po•em, Taking Poetry to the Streets, the Cana-Dixie Chi-town Union, the Written Word, Dual, Prepare Her for This, uncorrect, Living in a Big World (color interior book with art and with “Seeing a Psychiatrist”), Pulled the Trigger (part 3 of a 3 part set), Venture to the Unknown (select writings with extensive color NASA/Huubble Space Telescope images), Janet Kuypers: Enriched, She’s an Open Book, “40”, Sexism and Other Stories, the Stories of Women, Prominent Pen (Kuypers edition), Elemental, the paperback book of the 2012 Datebook (which was also released as a spiral-bound cc&d ISSN# 2012 little spiral datebook, , Chaotic Elements, and Fusion, the (select) death poetry book Stabity Stabity Stab Stab Stab, the 2012 art book a Picture’s Worth 1,000 words (available with both b&w interior pages and full color interior pages, the shutterfly ISSN# cc& hardcover art book life, in color, Post-Apocalyptic, Burn Through Me, Under the Sea (photo book), the Periodic Table of Poetry, a year long Journey, Bon Voyage!, and the mini books Part of my Pain, Let me See you Stripped, Say Nothing, Give me the News, when you Dream tonight, Rape, Sexism, Life & Death (with some Slovak poetry translations), Twitterati, and 100 Haikus, that coincided with the June 2014 release of the two poetry collection books Partial Nudity and Revealed.

|

Suddenly

Eric Burbridge

Sheet metal and screaming rubber copulated

A work of art flipped

Impaled flesh feared the darkness

Trapped pleas were answered by sirens

Powerful jaws freed the terrified

Motionless lay in a crimson pool

Another soul awaits judgment.

|

Minute

Eric Burbridge

Got one

Need one

Only had one

Just one

Wait one

Take one

Relax one

Go for one

Be back in one

Give me one

Last one

A sub atomic notch in time

Simple yet complex

Can’t live without it

|

Janet Kuypers reads poems from various writers from

cc&d v256, “Testament”

(Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem All In, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’ poem Junk)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon fs200)

|

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poems from various writers from cc&d v256, “Testament” (Including Sheryl L. Nelms’ poem Mental Nervous, Michael Lee Johnson’s poem Possum Slim (V2), G. A. Scheinoha’ poem Silver Anniversary, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozabal’s poem “Atonement”, Ronald Charles Epstein’s poem After Alberta’s Centennial, Eric Burbridge’s poem Minute, and Janet Kuypers’s poem Junk) live 8/5/15 at the open mic the Café Gallery in Chicago (Canon Power Shot)

|

Chicago Pulse

prose with a Chicago twist

|

Opportunity

Eric Burbridge

When Billy Bob got drunk he was the Tasmanian Devil of Jansen County; a friend, business partner and abusive of his lovely curvaceous wife, Mindy. That led to our affair and after seeing scars and bruises on her flawless skin, I hated him with a level head. When I pulled up to their wood frame house, the dual steel doors to his converted storm shelter, now his man cave, were open. I stood at the top stair. “Billy Bob, you in there?” I heard the short guy with the catcher’s mitt sized hands snoring. He said he planned on finishing the new room above his cave and adjacent to the kitchen today. Here I am and he’s drunk, again. Mindy deserves better. He told Mindy I was impulsive; I needed constant supervision. Isaac, the big guy with the small brain. I won’t get another chance like this. Good bye, asshole. I closed one door and left the other cracked. I backed my truck in the same two day tracks under the window of the work area. The bed was against the door of the man cave. I revved the big Power Stroke V8 diesel; a ten minute dose of carbon monoxide will send him on his way. And, for good measure, I went inside and worked while the engine idled. His accidental demise will be Mindy’s birthday gift before he kills her. Will she mourn long? If she does I’ll be there.

I tossed the remaining old drywall in the truck bed and finished enclosing the room. I was ringing wet from the humidity. I pulled up a chair and sat. My head hurt and I was dizzy. My cell rang and I put it on speaker. “Hey, Mindy, how are you?”

“Isaac, is Billy Bob there, he ain’t answering his phone?”

“I haven’t seen him.”

“Have him call the office.” Mindy said. An alarm went off in the next room. “Isaac that sounds like the CO alarm, Isaac, you dropped the phone Isaac...Isaac...Isaac...”

|

prose

the meat and potatoes stuff

|

Reclusive

Brian Looney

As if I was engaged in a cell phone conversation, discussing that which concerns us, only to find I never placed the call, and the screen displays some latent, static wallpaper which mocks the connection we never made, that best loved voice I never heard. Perhaps, even, we speak in different dialects, the varying inflections causing change in connotation.

Picture yourself walking, side by side with your favorite person, down some abandoned street at the most private time of day. You are encapsulated by your conversation, so that it excludes all else, even the physical form of the person you are with. Until, passing through the lamp-strewn shadow of a nearby building, that person vanishes entirely, and you emerge into the waning light alone. You realize you have been alone this entire time.

Like we’re in a room, you and I, conversing with each other on the same subject, only to find ourselves diverging. I funnel your words through my egocentric channels, molding them in my image, and erroneously, inaccurately responding. And you do the same. Like a pair of tramcars coasting along separate tracks, which head the same direction several miles from the station, but which suddenly veer apart without a warning. We continue several meters before we find we are unaccompanied.

I think, after all the self-analyses, the poetic deconstruction of my ego, and all its flaws and fears, the phrase, “Inside the shell, within the casement, around the corner and at the core,” best represents this out of touch existence. I wrote it in such a state, when I first discovered my reclusion, alone but for the barren ocean splayed out like an endless carpet, alone but for the ridges in the shell, alone but for the vacant echo of my thoughts against the grain.

|

Bathtub

Keith Kelly

“Do you know where my car keys are baby girl?”

“My guess is where you left them last, that being up your ass.”

“Ha ha, too funny.”

“I’ll help you look. What’s the deal, you never lose the keys, by the way how did you sleep last night?”

“Not so good, weird fucking dreams.”

“Oh yea, what about?”

“Uhh... something about a woman and a man looking through an old shed. They found a potion allowing them to switch bodies so they could understand what each other are thinking and why they did certain things.”

“That’s a weird dream. If people could switch places for a day, it would help us all get along better. Would you want to be me, your beautiful girlfriend?”

“I doubt so because if I was I’d have to deal with me, that’s something I wouldn’t like much.”

“You’re not so bad to deal with babe, you’re pretty laid back and easy going. What about me? Am I easy to deal with?”

“Oh no, that’s a trick question baby girl. I’m not answering that, especially since I am running late and have lost the keys. I don’t want a heavy conversation.”

“Come on answer me.”

“Ok, ok, mostly you are easy going, but sometimes you get in these difficult moods and can be rude.”

“Yea I’ve been told that before and am trying to be better.”

“You are fine baby girl; I love you just the way you are. Where the hell can those damn keys be?”

“You didn’t lock them in the car did you?”

“No I had them last night in the kitchen. Never mind, that’s where they are, by the sink. Yep here they are, I gotta go. Love you baby girl.”

“Love you to babe.”

“What are you doing back babe?”

“Now the car won’t start.”

“What are you going to do, are you going to go to work?”

“I guess, but I already missed my meeting, but it wasn’t crucial that I be there.”

“Well, stay home with me today and we can hang out.”

“I guess I can. By the time I get the new battery it’ll be noon anyway.”

“So go get the battery and come back for brunch and a movie.”

“Ok, be back in an hour.”

“Baby girl I’m back.”

“How’d it go, did the car start ok?”

“Yep, good as new.”

“Cool. What do you want to do this afternoon?”

“Oh I am up for anything.”

“We could take a bath and you can tell me how beautiful I am.”

“We don’t need to take a bath for me to tell you that, but a bath sounds nice.”

“The water is perfect babe.”

“Well, I know how my beautiful girl likes the bath water.”

“So do you really feel I am rude all the time?”

“What! I never said all the time, I said sometimes.”

“Am I rude a lot?”

“No, but when you get rushed or frustrated over something, you take it out on me.”

“I don’t mean to, it’s automatic.”

“That’s ok; I got my own shit that you have to deal with.”

“Yes you do babe.”

“Damn, no hesitation there.”

“Well, sorry but...”

“So what do I do that gets on your nerves?”

“I don’t know.”

“Yes you do, do tell.”

“Sometimes you act as if you’re better than everybody else.”

“No I don’t.”

“Yes babe you do. When you told me I was rude I accepted it and told you I’m aware of it and am working on the issue. When I tell you something about your behavior, you deny it.”

“Fuck, your right; it’s hard to admit my faults though.”

“Me to, but we all got em’, people who don’t own up are the most fucked up of all.”

“I agree.”

“So babe, in thinking about your dream last night what’s the first thing you’d do, if we switched bodies?”

“Hmmm, if I were you, I’d give me a blowjob.”

“You are a perv.”

“Or I’d sit around and play with my tits all day and never leave the house.”

“You are such a man.”

“Yes I am.”

“Be serious.”

“Ok baby girl, let’s see, I love you and I like the way you are. But still I’d fantasize.”

“About?”

“Oh let’s see, for starters, I would eat your friend Julie and be her lesbian lover.”

“That’s funny because I’ve wondered what it would be like to les out with her.”

“No way baby girl, are you serious?”

“Yep, but I will never act on it so don’t get so excited.”

“What if you were me, being the awesome man I am.”

“That’s easy, I would be more sensitive.”

“What do you mean, I’m sensitive.”

“You do pretty well, but sometimes you don’t realize how rough your tone is, and it hurts my feelings.”

“Ohhh I am sorry, I will try to work on my harsh tone.”

“Ok babe... So do you think we are compatible?”

“What?”

“Do you think we will be this close forever?”

“Well, I sure hope so. I can’t imagine being this close with anyone else. It’s been two months since we met, can you believe that?”

“Yes, it’s hard to believe. Do you like me more than your other girlfriends?”

“Jesus, that’s a trick question, I’m not sure how to answer that.”

“Well either yes or no, will be good.”

“It’s hard to answer because we’ve not known each other that long, and I care for you differently than them, because yall are different people. I care for others in different ways. Don’t you?”

“I guess so, ok, fair enough. Did you eat her pussy?”

“Holy shit, where is this coming from, I’m embarrassed.”

“Don’t be embarrassed, my last boyfriend ate mine.”

“Yes I ate her out. Why are we talking about this?”

“Isn’t this standard conversation in new relationships after a few months of getting familiar with each other?”

“I guess, but it’s catching me off guard. Ok, I got a question for you baby girl?”

“What?”

“How many men have you slept with?”

“Fifteen.”

“Fifteen! are you serious?”

“Well yes, why? How many women you been with?”

“Six.”

“That’s all, damn.”

“Damn, what do you mean damn?”

“Well men generally have more lovers than women, or at least say they do.”

“I said I’ve been with six women, I didn’t say how many people.”

“Oh my God, you’ve slept with men. That is so hot. So have you?”

“Yes two men.”

“Damn, fuck me now, I am so turned on.”

“Yea right. You’re silly. Have you ever slept with women?”

“A couple. I was in a committed relationship with a woman for about three years several years ago. I loved her.”

“So baby girl, what you’re saying is that your bi?”

“Yep, and you?”

“No, I was just curious I guess.”

“Your arms feel good around me in this silky warm water babe.”

“Yep, your body feels good in my arms as well?”

“So my handsome man was you the top or bottom with men?”

“Bottom.”

“What about you, were you the husband or wife in your relationship with that girl?”

“I was the husband.”

“Interesting, I was the wife, and you were the husband.”

“All of this talk is making me horny babe.”

“Me too.”

“I know something fun.”

“What?”

“I strap on a cock and make love to you.”

“Oh shit, I don’t know about that.”

“Oh come on, fantasize that I’m your last boyfriend and say his name over and over.”

“Fuck me, Ray, fuck me Ray. Like that?”

“Yes, just like that.”

“That was the best sex ever, my boo hinny is a little sore, but was great.”

“Yes it was, thinking of you going down on a man, makes me horny as fuck. What’s the biggest you ever had up in your ass?”

“Eight inches in my ass, about nine and a half in my mouth.”

“You?”

“My biggest ever is you babe. So when do I met your parents?”

“Parents! Damn you’re full of random topics and questions today huh? You don’t want to meet my parents, they are fucked, and I would never expose you to that.”

“You were not happy as a little boy?”

“Hell no, I was abused.”

“Are you serious?”

“Unfortunately.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Well, it is what it is. And your childhood?”

“Well, as a little girl, it could’ve been better, but could’ve been worse. My father was an alcoholic, he was a happy drunk, but undependable.”

“Better than a mean drunk I suppose, huh baby girl? Is that why you became a therapist?”

“Probably, it’s a field you don’t choose it chooses you.”

“I see.”

“And you, why did you want to be a stock broker?”

“Because I wasn’t a good enough musician, plus I make good money.”

“How much money do you have in the bank? I’m just kidding.”

“I do ok, I am not ready to answer that in case you weren’t kidding, after all we’ve only known each other two months.”

“Ok, but I’ve very little in the bank, but no debt, just want you to know where I stand.”

“I make enough to make sure we are always ok, not a worry. Okay.”

“Okay Mr. Man.”

“So back to the parent’s conversation, mine are judgmental idiots; I haven’t spoken to them in years.”

“Judgmental, let me guess they wouldn’t like their son bringing the colored girl home?”

“Hell no, that’s why I don’t talk to em’, they never accepted the fact I like black girls, my parents are morons.”

“Will you ever speak to them again?”

“I don’t plan to. How do your folks feel about you seeing a white guy?”

“Shit, they don’t care as long as I’m happy.”

“And are you happy?”

“I’m jubilant, and I want to see where this relationship leads.”

“Yea, me to.”

“We should take off every day and soak in the tub; I could hold you in my arms every day for the rest of my life.”

“Awe babe that’s so sweet. Did you know that during the first few months of a relationship that chemicals are released in the brain mimicking drugs?”

“Ok so what you’re saying, these feelings aren’t real?”

“No that is not what I am saying, but during the honeymoon phase couples don’t act clearly and it’s recommended not to make any big decisions during this time.”

“Yea I’ve heard, sure is fun though huh?”

“Yep. The stronger the honeymoon phase of a relationship is, the stronger the overall relationship will be. I feel a couple can experience aspects of the honeymoon phase regardless of how long the relationship last.”

“Well, that is something to look forward to then.”

“So do you like your job as a stock broker?”

“It’s ok, pays good, but stressful.”

“What made you interested in being a broker?”

“My dad was a broker before retiring, and I always found it interesting so I followed in his footsteps.”

“That’s surprising since you don’t have a relationship with him or anything.”

“Yea, I guess. If I could be anything I wanted I would be a racecar driver, or a porn star.”

“Oh, shut up, I’ve known you two months, and I’ve already discovered you are shy when it comes to stuff like that. You can’t even pee if I can hear it.”

“I know, I’m joking. So Thanksgiving is next week, what are you doing?”

“That’s, funny I was going to ask the same thing?”

“I won’t do much baby girl; go to sisters for dinner, that’s about it.”

“I’m going to my parents and thought about asking if you wanted to come, but it may be a little too soon. Huh?”

“Yea, probably, I am not ready, but soon maybe.”

“Stand up a minute gorgeous, let me see that beautify feminine body, let me hit that ass.”

“Again?”

“Hell ya.”

“Ok, just make sure you fuck the shit out of me; rock my mother-fucking world.”

“Damn, you’re talking all gangster.”

“Your too funny babe.”

“That was awesome, your cock is incredible, Jesus!”

“You’re not so bad yourself.”

“The water is getting cold, ready to get out babe?”

“Yea, then what do you want to do?”

“I want to split a large pepperoni pizza and eat a whole bag of Hershey’s kisses, watch a movie, and take a long nap.”

“That sounds awesome, what an awesome day; I’m never going back to work.”

|

The Rotten Ones

Sarah Szabo

The rook sailed southward, its black wings spread wide against the blue sky while Lee Sung-Ki watched it go from the earth below. He did not know what kind of bird it was—he knew little of birds at all—but he knew that it could fly, and as it disappeared from his sight into the backdrop of green trees on distant hills, he wished that he could follow. To be away from the stone and steel, to see forbidden cities—that’d be truly something, Sung-Ki thought.

Not today, though. Today was school, and hunger, as yesterday was, as tomorrow would likely be, and it was not his lot to complain. As he turned and blinked, his eyes dazed from gazing upward into the bright blue of the morning, someone’s fist bumped him, not lightly, on the shoulder.

“Heads up, kid,” another boy said, wheeling around from behind to the front of him.

“Oh. Good morning, Woo-Yung,” Sung-Ki said. Ahn Woo-Yung was the other boy’s full name, and Sung-Ki regarded him as he hopped from one foot to the other, restlessly, his lanky limbs dangling at his sides. He was a year older than Sung-Ki, perhaps less, but easily two heads taller. His face, more ugly and red-dotted from day to day, was set, as was typical, in the expression of a lazy grin. Both his shirt and his skin looked dirty, at least three days in to needing a vigorous wash—not that it seemed much to concern him.

“What’re you doing, staring at up there,” asked Woo-Yung. “See a balloon?”

“I didn’t see you at school yesterday,” Sung-Ki said, ignoring the question. “Did something happen?”

“No, everything’s great,” Woo-Yung said, dismissively, as he dug something out of his nose with his thumb. “I found something better to do, though. You should come with me.” Woo-Yung had a worn and torn old baseball with him, which he was tossing high in the air with one hand and catching in the other, casually, while he talked.

“Come with you?” Sung-Ki looked at his feet, and shifted his weight from foot to foot. “Now?”

Woo-Yung nodded, lobbed up the ball again. “Right now.”

“What for?”

“Guess.”

“To... play baseball?”

“No, stupid,” Woo-Yung said. “Where would we play baseball at?”

Sung-Ki wrapped his thumbs around the straps of his knapsack, growing anxious at the thought of skipping school. “I don’t think it’s a good idea, especially for you,” he said. “You can’t miss two days. You’ll get in trouble. I’ll get in trouble.”

“No, you’ll get in trouble if you don’t come with me,” Woo-Yung retorted, in a teasing tone. “Because what I’ll do, if you don’t come? I’ll tell everyone we know that Lee Sung-Ki was too cowardly, too scared, too much of a teensy shrimp to go on an adventure. And that’ll be who you are. Forever.”

“Please don’t.”

“Then come with me.”

Sung-Ki looked around warily, as though he would only be able to join the older boy if he slinked away with no one seeing him. He had, of course, already made up his mind.

“Where are we going?” he asked the other one, a devious smile dawning on his face.

Woo-Yung threw the baseball terrifically high in the air, skipped backwards into the street, and caught it in both hands, just above his eyes. “It’s a bit of a walk,” he said. “I’ll tell you on the way.”

|

Kim Yu-Ri was shifting her weight from foot to foot as she stood by the unshaded aisle in Chongjin Market, eyeing the burlap sacks across the way. Inside the tops of them, just beneath their folds, she could spy little white grains of rice piled high, amounting to twenty pounds a bag, or maybe more. Her legs were sore, the bones and muscles both, her ankles creaky and her calves tight from the strain of standing up so long, after so little sleep, so soon after yesterday. But she refused to sit down, knowing that her best chances of being noticed by passing shoppers required being seen—her, and her baby both. The child was strapped up in a swaddling cloth held taut around Yu-Ri’s shoulders and cradled in her arms, swaying side to side, asleep. Her name was Lee Su-Dae.

Yu-Ri knew that she could easily set the baby down; that if she did, she’d likely go on resting, not be fussy, and also be one less burden for her weary body—but she could not chance looking so relaxed. It would ruin the picture.

“Eggs,” she said aloud, to the walkers, walking by. “Fresh eggs.”

No one looked up—some were on their way elsewhere, some were drawn instead to the rice grains bagged in burlap. Another group approached, and she repeated her pitch toward them.

“Eggs? Fresh eggs.”

Beside her, her two chickens clucked, and bawked, and flapped their wings within their cages impotently. She had a dozen eggs cloth-cushioned on a barrel above them, arranged together in a clean and neat display.

“Eggs,” she said again, to no one. “Fresh eggs.”

|

Far from the streets and garbage-clogged gutters, the two boys walked, more than an hour then into their journey—Woo-Yung’s grand adventure. The older one had remained obstinate all the while, refusing as yet to explain to Sung-Ki where their endpoint was, beyond an assurance that, yes, there was one. Then again, Sung-Ki had not pressed the question too vigorously. Woo-Yung, after all, was older, surely wiser, possessing of a casual self-assurance that opposed all of Sung-Ki’s reservations, and made his worries seem trivial. Maybe it was because he was so tall. Still though, despite the older boy’s confidence, Sung-Ki was inwardly becoming more and more irresolute, the further they walked through trees and brush increasingly tangled, up the uneven rocky mountainside that bordered the city’s south.

The sun edged up toward its noontime peak, its light hazy through the wooded ceiling of the forest. Sung-Ki wondered what he was missing at school—if his absence had even been noticed. He considered that it was possible that his class had been tasked today with taking their bowls to the industrial riverbanks, to pick corn kernels from the mud—and with that in mind, he found it hard to regret taking a day for himself. Still, the long walk uphill he was taking now was not what he would have chosen for his free day, given the option. The skin beneath his shirt was slick with sweat, and his head swam in the mounting heat. With increasing frequency, as he ambled clumsily over the occasional stone half his height with his hands, his vision was drowned in a fuliginous silver fog as dizziness took over, his bloodflow laboring to keep up with the day’s unusual demands and failing at every other turn. With the straps digging into his shoulders, he wished he had thought sooner to find a place to leave his backpack for later retrieval. He wouldn’t chance it now—the hillside was all unknown, and the trees all looked too similar.

“It’s not much farther, now,” said Woo-Yung, still heaving his baseball in the air at every pause in his step, not at all obviously tired.

“I wish you’d told me how far this would be,” Sung-Ki protested. “I would’ve left my bag at home.”

“No, no, we’ll need it,” said the other, his meaning ambiguous. “Give it here, though, I’ll carry it.”

The lightened load was welcome, if too late to keep a creeping ache from setting in to Sung-Ki’s back. “How much farther?” he asked.

“We’re almost there. Trust me. You’ll be glad you came.”

It was hardly five minutes later that Woo-Yung halted his advance, slinging Sung-Ki’s bag onto the ground and spinning, eyes up, searching for something. Sung-Ki halted just below him, hands on his knees, unhappy. If this was the place, Sung-Ki thought, then he would have to seriously consider reevaluating his friendship with the older boy. There was nothing remarkable here to his eyes; the same brown trees, the same stony ground—not even a decent view of the city below. He felt a bead of perspiration form on the tip of his nose, and followed it with his eyes as it slipped and fell onto the ground between his feet.

Within the leafy detritus, something orange caught his eye.

“This is it,” said Woo-Yung. “We’re here.”

Sung-Ki knelt, not immediately responding, and gingerly brushed away the dirt and dust from the flesh of the rounded fruit, lifting it delicately from the earth between two fingers. It was small, small enough to fit fully in his dwarfish hand, and soft enough that even his wary grip was strong enough to make its skin give just a little, seeping pungent juice. A trio of ants darted across Sung-Ki’s fingers, and he gently shook them off.

“It’s an apricot,” he said.

“They’re all apricots,” Woo-Yung replied. And for a moment, Sung-Ki took the comment with confusion, looking first between his feet to see if he’d missed many more on the ground around him. Then he cast his eyes at Woo-Yung, and followed his pointing finger toward the nearby trees, up, up into their branches, into the leaves, high up near their very tops where dozens more were nestled, swaying by their stems in fruiting bloom.

Sung-Ki’s expression said more at that moment than any words could muster, and Woo-Yung leapt the distance between them with a grin on his face, clapping the young boy on the shoulder. “See? See? I told you you’d love it,” he said.

Though his mouth watered, Sung-Ki paused before taking a bite of the fruit in his palms, raising it first to Woo-Yung. The older boy leaned over and sank his teeth in, spurting juice upon his face and onto Sung-Ki’s hair. “Oh, god,” said Woo-Yung. “It’s so ripe.”

“I think it’s rotten,” said Sung-Ki, bringing the fruit to his lips for a bite of his own. Its innards were all goo, hardly the firm shapeliness he figured a fresh one, right off the vine would have.

“They might all be rotten,” said Woo-Yung, licking his lips and fingers. “Still, open your bag up. I’ll climb the tree and see.”

Sung-Ki darted up the rocks and grabbed his backpack, dumping out the heavy books inside it to make room for what he hoped would be a bounty large enough to fill up the entire space within. At the same moment, lean and slender Woo-Yung made an effortless leap up to one tree’s lowest branch, and the leaves rustled loudly at his touch. Sung-Ki looked up, and squinted, unsure if he could see any fruits in bloom immediately above him, where Woo-Yung would be able to reach.

But below the branches—that was different. His eyes open with renewed focus, Sung-Ki scanned the stony ground, its piles of brittle wood and dying leaves. As his gaze adjusted to the patterns of the forest floor, the fruits revealed themselves to him. One, two, two more—he dropped to his knees, and scooped them toward his bag, leaves and dirt and all. One squished entirely at his touch, so he balled it up and ate it there, on his knees, instead.

“I’ve got one,” said Woo-Yung. “Sung-Ki, I’ve found one, catch it.”

He looked up just in time to see the falling fruit before it hit him square between the eyes, and unlike the ones down on the ground, this one was firm, fresh, and painful. “Oops,” Woo-Yung said, a chuckle in his voice. Sung-Ki picked it up and took a spiteful bite out of it, intending to save the rest for the older boy—but the fruit tasted so delicious, that he devoured it down to the pit instead.

“Are there more, down there?” called Woo-Yung, advancing ever higher into the ceiling of the forest. “They must have all fallen... There were so many more on the lower branches, last time I was here.”

“There are some,” said Sung-Ki. “But they’re all soft, and old.”

“Get them anyway. I’m going to climb higher... There are dozens, higher up, but I can’t reach them yet.”

“Shake the branches,” Sung-Ki suggested, digging around for the squishy fruits already fallen. He looked around toward the other trees, wondering what was hidden in their branches, if anything. “Maybe you should climb another one,” he said. “I can’t tell if there are any others, any lower. But maybe.”

“Give me a second,” said Woo-Yung. And then there was a loud commotion of branches snapping, leaves shaking, and panicked, heavy breath, and Sung-Ki started, fearing the older boy had fallen, or worse yet, was falling down on top of him. But he had only jumped from one branch to another, and as he paused there up above, there was another violent rustling down below, and Sung-Ki finally realized that the sound was not Woo-Yung’s doing, nor the breeze—it was something else.

Someone else.

“What do you think you’re doing here, you filthy ratshit thief.”

Sung-Ki whirled on his heels at the sound of the voice, a man’s gravelly snarl, furious and low. In his panic, his feet caught beneath an unseen root, and he tumbled, twisting, to the forest floor. “I’m sorry,” he said, reflexively.

The stranger loomed above him, hunched over inside a torn brown coat, with perhaps no other clothes beneath. His hair was dark, long, and tangled like a bird’s nest, his mouth a grimy scowl. He looked like a creature born from mud, as much earth as he was man, with all the caked-on grime—and in his blackened, filthy hand, the knife shone all the brighter. “What do you think you’re doing here,” the stranger growled again.

Sung-Ki was stammering malformed apologies, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” sinking more and more into the wet leaves when he should have been pushing himself up by now and sprinting far away. He knew it, yet still he could not manage to rise. He heard someone call his name, but did not at first understand why.

“You have my fruit in that bag there? Hm? Is that what you have there, in that bag, boy? My fruit?”

Before Sung-Ki could speak or plead or beg again, Woo-Yung hit the ground behind him, and grabbed him beneath the arms, dragging him back into his grasp. “Get up,” he urged. “Get up, get up.”

“Get away from my tree.”

“It’s not your tree, creep,” Woo-Yung barked. Sung-Ki, trembling, finally got back onto his feet, and Woo-Yung pressed him backwards, shielding him with his arms. “Get the bag,” he said, beneath his breath.

The stranger took two steps forward, growing lower and more feral as he approached. The knife twisted in his hand. Its blade was as jagged as its wielder’s yellow teeth, its point reddened with rust, or worse. “Empty it out,” he said.

“Get the bag, Sung-Ki.”

Sung-Ki turned, snatched up his backpack, and began to try and zip it shut. But some of its fruits had spilled, when the man surprised him, and when Sung-Ki moved to raise it, he saw five more fruits beneath, newly-revealed... He couldn’t leave them. All he could hope was that the stranger wouldn’t see him move, as he clumsily shoveled them in with the rest. It was a poor decision.

The stranger did not bother even speaking—instead, he roared, charging over the rocks and leaves toward the both of them, and Woo-Yung shoved Sung-Ki away. The boy kept his footing but he lost more fruits, and by now he had no choice but to go, as fast as he could, lest he be stabbed, killed, eaten by the wild, filthy mountain man. He dared not turn around to see how close his knife was. “Run, run!” Woo-Yung shouted, as though Sung-Ki needed to be told.