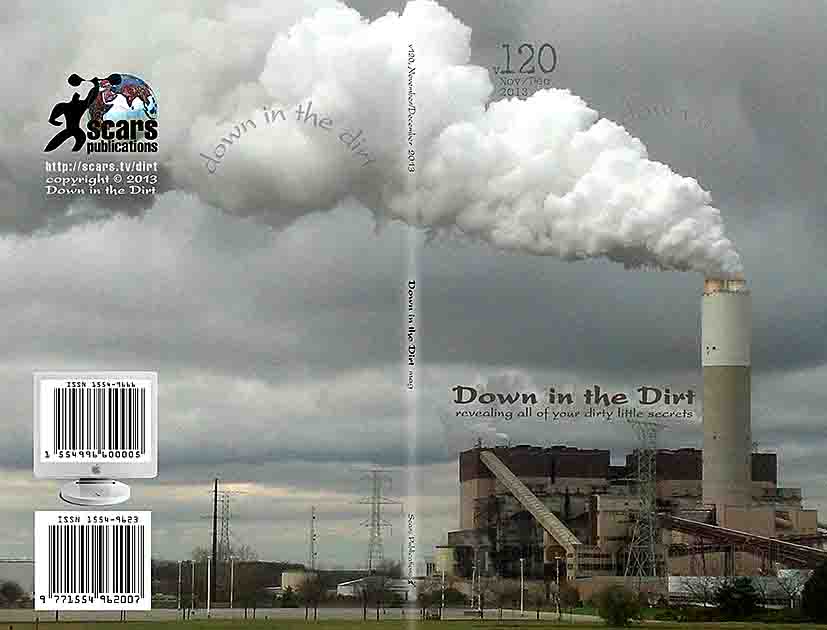

welcome to volume 120 (the Novelber/December 2013 issue) of

![]()

down in the dirt

internet issn 1554-9666

(for the print issn 1554-9623)

Janet K., Editor

http://scars.tv/dirt

or http://scars.tv - click on down in the dirt

Note that any artwork that appears in Down in the Dirt will appear in black and white in the print edition of Down in the Dirt magazine.

|

Order this issue from our printer as an ISSN# paperback book: |

![]()

Christmas CliffMCD12/24/2012

I got the greasy pizza blues

I swore off the booze long ago

so when you see me with my

maybe a buck eighty

so ho ho ho, I wish you

|

![]()

Down in the DirtMarlon Jackson

So cool it is to read all types of different things

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads poetry from Down in the Dirt, v. 120, the November / December 2013 issue “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

Goodness GraciousMarlon Jackson

So soothing a touch can be...

|

![]()

Another GenerationKerry Lown Whalen

Tension sat in Fran’s gut. She had to phone her uncle and invite him to dinner on Saturday night. From her standpoint, the news she’d be forced to reveal wasn’t a cause for celebration. Her uncle picked up the phone after the third ring.

|

![]()

Maybe Liam Spencer

It’s all disposition, they’ve never done better

I don’t argue. There is no chance.

|

Two Letters Liam Spencer

the cell phone

|

![]()

MentorJason D. Cooper

From hidden cocoon

As storm cloud skies

Just to immerse

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads poetry from Down in the Dirt, v. 120, the November / December 2013 issue “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

Safe WordJason D. Cooper

Bound and fettered

Your bejewled mind

By shouted whisperes

|

![]()

My Secret BrotherSteven Wineman

My brother Jimmy is in prison in Michigan for molesting boys. Those are words I very rarely speak out loud.

Jimmy was arrested in the February 2000 after two teenage boys reported that he’d invited them for a ride in his car and then fondled them. My brother was driving an expensive sports car, a Dodge Viper. A little while after the actual incident, the boys were in their school bus and noticed his car. They started talking about him, something along the lines of “there’s that creep in the Viper.” An attentive bus driver heard this, asked the boys questions, and then called the police.

One of my earliest memories is of Jimmy chasing me around our apartment when I was four and he was eight. We had recently moved from Detroit to New York. It is the first time I can remember him doing something that scared me, though I can’t really place memories of him before this event, positive or negative. I also don’t remember specifically what he did that day that scared me so much – chase games aren’t necessarily frightening – but I know I was terrified. Nor do I remember where our mother was. It was not a big apartment and she was a stay-at-home mom at the time, but she was nowhere in sight. To get away from Jimmy, I ran into the bathroom, pushed the door closed with all my might, and turned the bolt to lock it.

My mother’s account of my brother’s childhood, which I heard many times, was that he was a perfect baby and a really good boy until he was eight, when he abruptly turned bad. I don’t know if the Steven-getting-locked-in-the-bathroom incident was the turning point in my mother’s eyes, but it was in mine. After that, Jimmy tortured me for six years.

Jimmy liked me. I understood this as a child, in some deep, almost nonverbal way. When I was four he taught me to play chess, and he crowed to our mother about how smart I was. I don’t remember pondering the weirdness that he could both like me and abuse me. Jimmy was just plain weird, and was also very explicitly defined as the bad kid in the family. That was plenty to ponder, and it simply led me to do everything possible to not be like him.

My mother told chilling stories about what a “good” baby my brother was. One of them was about taking Jimmy on the train from Detroit to Seattle when he was still an infant. My mother would recount how for three days on the train, Jimmy never cried. It defies belief, that it could happen at all and what mayhem must have been going on inside a six month old to clamp down on every natural, healthy urge and need of his own in order to stay quiet and satisfy his mother. When Mom told the story, there was never any hint that this might have been even slightly messed up. For her it was a golden memory.

The counterpoint to all the secrecy about my brother has been my urge to tell. Interspersed with many years of silence, I have gone through various phases of telling.

The body, however, does not forget. I have had stomach aches since childhood. They come at unpredictable intervals, but when they hit they can be excruciating, to the point that all I can do is lie down. At a more tolerable level, I have gastric distress every day without exception and have had for many years, so much part of my life that I would not recognize myself without it. Intertwined with the gastric junk, my stomach and intestines are where I carry my anxiety, also with the volume notching higher and lower but always present to some degree. I can’t tolerate being tickled, or being touched on my stomach unexpectedly.

In late 2002, I slogged through my ambivalence and started writing to Jimmy in prison.

Jimmy’s first letter back to me was dated December 5, 2002.

How do you hold the terrible reality that someone can be a victim and a perpetrator at the same time?

After my efforts to have a real conversation with Jimmy about our childhood, the correspondence subsided into what for me was mostly chatter – who would win the Super Bowl? who would win the presidential race? It also slowed way down, as there were longer intervals in my replies to his letters. The only point for me was to maintain some minimal contact – for the sake of what? I think I was trying to strike that precarious balance between compassion and self-protection; between loyalty to my child self and this ongoing effort to be an adult; between the undeniable reality that Jimmy is a critical part of my history and shaped way too much of who I am, and the undeniable reality that there was no meaningful dialogue happening between us.

The sexual abuse of children is a problem of epidemic proportions. As many as 40% of all girls and 20% of all boys are sexually abused at some time in their childhood. According to the National Center for PTSD, strangers account for 10% of incidents of sexual abuse of children; 30% of perpetrators are family members; and 60% are otherwise known to the victims and their families. In their extensive review of the child sexual abuse literature, Karen Terry and Jennifer Tallon note, “All researchers acknowledge that those who are arrested represent only a fraction of all sexual offenders. Sexual crimes have the lowest rates of reporting for all crimes.” (“Child Sexual Abuse: A Review of the Literature,” p. 3.)

My brother is sixty-eight and has now served about ten years of his 10-15 year sentence. In all likelihood Jimmy will get out of prison some time in the next five years.

A story changes in the retelling. Even when the events themselves have not changed, the narrator inevitably has, producing subtle or larger changes in the point of view from which the narrative is retold. In this case, Jimmy’s story (which is also my story) continues to unfold. So not only am I a different story teller now than other times I chose to reveal my secret brother, but I’m also telling a larger and even more textured story. And of course this effort to re-break a silence is also a retelling of the story to myself.

|

![]()

Drunk FatherRoland Stoecker

my sister and I

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads poetry from Down in the Dirt, v. 120, the November / December 2013 issue “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

![]()

Rushing the ScoutHannah Thurman

The day before his sister’s wedding, Lee leaned against the refrigerator, watching his father argue with the groom-to-be and hoping this would be the fight that would wreck whole thing.

Lee shut his door and looked at the time. It was a quarter until two, which was when the rehearsal was supposed to start, but he’d seen enough of Meredith and his father’s fights to know that he had a while. The two were both hot-tempered and could argue for a long time. Lee, on the other hand, did not like confrontation; in that way, his father said he took after his mother. Besides a proclivity to argue, memories of her were another thing Meredith and his father shared that he did not: Meredith had been six when she died, Lee only two. It was hard to miss someone you didn’t remember.

The tent on the lawn of Townsend’s parents’ country club was already hot. By the time he had finished his part of the rehearsal, he wanted to jump into the golf course water trap. He lay down on some folding chairs in the back, listening to Meredith’s sorority sister/bridesmaids practice their readings. There were eight of them, all with straight brown hair and tank tops in varying pastel shades. They were the types of girls Meredith had hated in high school; he had never expected her to join a sorority, but then again, he had never expected her to get married at twenty-two, either. If the wedding hadn’t been in the works for six and a half months, he’d have thought she was knocked up. . . . That was the only way he would ever justify her marrying Townsend.

After the rehearsal, Lee and his father walked across the hot parking lot, fanning themselves with programs. Lee wondered if today’s heat would help Meredith’s fan cause. Lee wished she were riding with them, even though he was mad at her. He never knew what to say to his father when it was just the two of them.

Meredith came into his room late that night as he was trying to convince Max to start another game. When he’d gotten back from the rehearsal, the three guys had been away, driving Aaron’s brother’s car to pick up a futon they’d bought on Craigslist. Now that they were back, Max said he was tired and Aaron and Brendan followed suit.

The wedding was held under a bright white tent and even the last-minute addition of four hundred handheld fans didn’t make it any cooler. Lee stood behind Townsend, sweating, as Meredith said her vows. Townsend was wearing a linen jacket and didn’t seem too uncomfortable but Lee’s tux was heavy and tight. He’d bought it for band concerts before he got into college and quit trombone, and the cummerbund felt like a heating pad cinched around his waist. He wished he were at the pool with Max and the other guys. At least he hadn’t had to talk to Townsend yet.

The halls of the country club were gray; it was beginning to get dark outside. He paced back and forth for a minute, dress shoes clicking on the shiny tile. Then his father burst through the door.

|

![]()

PoppyS. R. Mearns

Why is my poppy plastic

Like memories of those

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads poetry from Down in the Dirt, v. 120, the November / December 2013 issue “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

![]()

Supply and DemandPeter McMillan

“On the savanna, the lion outruns and slaughters—”

Martin was an ordinary eight-year-old kid. He didn’t wear glasses and he dressed normal—nothing from the thrift store and none of that faux-hood clothing—but he was the new kid. His family had just moved to Toronto, and he hadn’t made any friends.

The next day six black leather jackets cornered him in an alley, but Martin was ready.

|

Peter McMillan BioThe author is a freelance writer and ESL instructor who lives on the northwest shore of Lake Ontario with his wife and two flat-coated retrievers. In 2012, he published his first book, Flash! Fiction.

|

![]()

A Norman Rockwell LifeCarol SmallwoodExcerpt from Lily’s Odyssey (print novel 2010) published with permission by All Things That Matter Press. Its first chapter was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Award in Best New Writing.

When I saw Dr. Bradford next, I said, “I keep running but I know I must face what happened.”

|

About Carol SmallwoodCarol Smallwood co-edited Women on Poetry: Writing, Revising, Publishing and Teaching (McFarland, 2012) on the list of “Best Books for Writers” by Poets & Writers Magazine; Women Writing on Family: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing (Key Publishing House, 2012); Compartments: Poems on Nature, Femininity, and Other Realms (Anaphora Literary Press, 2011) received a Pushcart nomination. Carol has founded, supports humane societies.

|

![]()

Daddy’s Lil’ ToyKelly Haas Shackeford

Small eyes look up questioning why she

|

|

Janet Kuypers reads poetry from Down in the Dirt, v. 120, the November / December 2013 issue “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

![]()

SnakeskinRyan Priest

Robert woke up at twelve-thirty in the afternoon and made an a-line directly through his small studio apartment and into the four foot by five bathroom, carefully dodging old beer bottles and plates. He yawned, smacking his lips and casually relieved himself. More bottles, cans, wadded up pieces of paper and stiff dirty clothing littered the floor so badly that it was impossible for one to stand completely level while inside. Tammy, his girlfriend, had been on him for weeks to clean.

|

![]()

RandallGraeme Scallion

I trade my math textbook for my lunchbox and slam my locker shut. As I seal the lock, Randall materializes in the reflection of the neighbouring locker. I turn and smile. A seventh grade girl rarely strays into the ninth grade hallway, but Randall ignores the glares and catcalls. Her blonde bob and square-framed glasses emphasize nervous blue eyes. She looks in every direction but mine.

|

![]()

AbscondEric Prochaska

To the dismay of early April commuters wearing either light jackets or blouses alone, the afternoon buses ran the air and the evening subways worked their heaters.

“If I had known we wouldn’t even get a nibble, I probably wouldn’t have bothered,” I said, looking out the window at the vaguely blue dark. The rhythm of the train rolling over the joints in the tracks was a comforting soundtrack.

That was soon after the abortion, when we were still sure we were going to make it after all.

|

Eric Prochaska BioEric Prochaska has published short stories in some of the finest places, including riverbabble, Digital Americana, Eclectica, The Morpo Review, Doorknobs and BodyPaint, Whistling Shade, Amarillo Bay, and others. He lives and teaches Illinois. His first collection of short stories, This Great Divide, was published by Halo Forge Press in 2006.

|

![]()

Devil’s PostpileJohn Ladd Zorn, Jr.

“I’m sorry the wedding is on the same weekend, but the trip is set, and I’m not going to miss it for someone’s lame little prom,” Jay said.

The glass lid over the salad clanked gently against the serving dish an hour later each time Jay braked in the stop-and-go traffic. Elizabeth had insisted he drive a hundred miles round-trip to go swimming in the bride-to-be’s pool before he left.

“You prefer the company of your boyfriends to me,” Elizabeth said as he bent to kiss her good-bye.

Throughout the six hour drive, he and Sota said next to nothing. Jay’s book of Hemingway’s letters sat unopened on his lap while he tried to justify fishing. His mind was, as Hemingway used to say, bitched.

Jay slept well. It was not so cold. The ground was not too hard. He awoke after sun up. He poured whiskey into the coffee in his thermos and sipped it while he read Hemingway’s letters. Elizabeth has a point, he thought, really he’s just a crazy egomaniac. Maybe reading this is what has my soul and body all out of alignment. He closed the book and checked over his rods and tackle. His gear was an embarrassment. Two of the rods were broken and held together with electrical tape. He hadn’t had the time or money to get new equipment.

Mac had gone to town and come back with beer, bacon and eggs. Jay got the fire started and tended to the bacon and eggs. “I had a cel signal in town and Mom called,” Mac said to Jay. “She said Annie was crying and saying she was afraid something bad would happen to daddy.”

After they had eaten, they hiked through the woods to Starkweather Lake. Jay waded in up to his belly and tried casting and reeling various lures, spinners and spoons, but got no action. The trout were striking at insects on the surface. Fly fisherman floating in tubes were catching a few, but Jay didn’t have the right gear for that. He stayed in the water three hours, the sun cooking his face and shoulders, the water freezing his testes. When he got out, the air temperature was in the seventies, but Jay shivered for an hour. Long after he had dried off and changed into dry clothes, his body was quaking, his fingers, calves, and toes were numb. When sensation came, it was in painful pricks.

When he awoke, his entire being was mosquito-bite itch like it was some circle of hell. They drove up to Red’s Meadow and bathed at the hot springs, where the little waterfall rushes down the hill with the wildflowers all around it. They struck camp and loaded up before noon. All the way home through the barren desert mining country, Jay’s excitement to see his wife and daughters grew. He wished he could snap his fingers and be with them instantly.

|

About John Ladd Zorn, Jr.John Ladd Zorn, Jr., B. A., U. C. Irvine, Certificate of Fiction Writing, U.C. Riverside, lives on the edge of the Mojave Desert and the Southern California megalopolis, and is the author of several short stories including “Booze, Voodoo and Ex-Lovers,” Phantom Seeds #3 (Heyday Books), “Whale Song,” Inlandia. He is working on his second book, Maineiac, drawn from his experience working on a lobster boat in Maine, where he’d driven from California to tell a girl he loved her and is completing a Master’s Degree in Higher Education. He is a former Jeopardy! Champion.

|

![]()

diogen 111, art by Eleanor Leonne Bennett

Eleanor Leonne Bennett Bio (20120229)Eleanor Leonne Bennett is a 16 year old iinternationally award winning photographer and artist who has won first places with National Geographic,The World Photography Organisation, Nature’s Best Photography, Papworth Trust, Mencap, The Woodland trust and Postal Heritage. Her photography has been published in the Telegraph, The Guardian, BBC News Website and on the cover of books and magazines in the United states and Canada. Her art is globally exhibited, having shown work in London, Paris, Indonesia, Los Angeles, Florida, Washington, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Canada, Spain, Germany, Japan, Australia and The Environmental Photographer of the year Exhibition (2011) amongst many other locations. She was also the only person from the UK to have her work displayed in the National Geographic and Airbus run See The Bigger Picture global exhibition tour with the United Nations International Year Of Biodiversity 2010.

|

![]()

Marsha RichardsonMike CluffBigotry can be polite, but still destructive and despicable no matter its degree

“I do not like this new

it will complicate

who will prune my fuschias Rosita proved that well to me,

water my dicondra lawn

wipe the bowl

I will force Frederick

there I can

we would all be

|

![]()

A Beautiful NightDarcy Wilmoth

I’ll never forget the day I met my conscience.

I had had a nagging feeling for most of the week. Something, I felt just wasn’t right.

As I was hurrying down the sidewalk, heading toward the coffee shop to get my usual Wednesday morning vanilla latte, I noticed a man standing in the middle of the sidewalk, letting the rain soak him as if he didn’t even notice. He watched me running towards him, hiding behind my umbrella, trying to avoid getting wet. He was a man of average height and build, with thin-rimmed glasses and dark hair that was nicely groomed and brushed to the side. He had one of those faces that people are drawn to, not necessarily handsome but one that was easy to look at.

Then it hit me.

On the day I decided to do it, I wanted to take one last walk with Albert. It was evening, and just starting to cool off. There was a smell in the air that signaled the changing of seasons. This had always made me feel alive, especially at the beginning of fall.

Suddenly I looked up and noticed how many stars were in the sky on this particular night.

|

![]()

Seeing a Psychiatrist:

Janet Kuypers |

Watch this YouTube video live in the show Seeing a Psychiatrist 09/09/08, Chicago at the Cafe |

Seeing a Psychiatrist:

Janet Kuypers |

Watch this YouTube video live in the show Seeing a Psychiatrist 09/09/08, Chicago at the Cafe |

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading poetry Volume 246, the November / December 2013 issue of cc&d magazine (including the poems “Seeing a Psychiatrist: Hopelessness and Futility” by Janet Kuypers, “Daddy’s Lil’ Toy” by Kelly Haas Shackeford, “Drunk Father” by Roland Stoecker, “Poppy” by S. R. Mearns, “Down in the Dirt” by Marlon Jackson, and “Mentor” by Jason D. Cooper), live 12/4/13 at the open mic the Café Gallery at the Gallery Cabaret in Chicago (C) |

Janet Kuypers Bio

Janet Kuypers has a Communications degree in News/Editorial Journalism (starting in computer science engineering studies) from the UIUC. She had the equivalent of a minor in photography and specialized in creative writing. A portrait photographer for years in the early 1990s, she was also an acquaintance rape workshop facilitator, and she started her publishing career as an editor of two literary magazines. Later she was an art director, webmaster and photographer for a few magazines for a publishing company in Chicago, and this Journalism major was even the final featured poetry performer of 15 poets with a 10 minute feature at the 2006 Society of Professional Journalism Expo’s Chicago Poetry Showcase. This certified minister was even the officiant of a wedding in 2006. |

![]()