These Neighbors

Clay Carpenter

These neighbors you never

talk to are out working in the

yard. You remember a conversation

three, four years ago. He

said they might move one day,

pack it up, back to Houston,

when their daughter graduates

high school. It seems

strange, imagining the

neighborhood without them,

the white minivan in the

driveway across the street.

They lived there when you

moved in, 16, 17 years ago.

Your kids played together

when they were small, until

they decided they didn’t like

each other. But the adults

always got along. Still, you’ve

never talked with them

as much as you should, never

made good on the occasional

overtures of friendship. A

flimsy attempt every

few years, a dinner that was

perfectly fine, then months of

hardly a word. But when they

move out -- you feel it now like a

a hip that suddenly has gone

arthritic -- a chasm will open

and something will die, a

piece of your life gone with these

neighbors you never talk to.

|

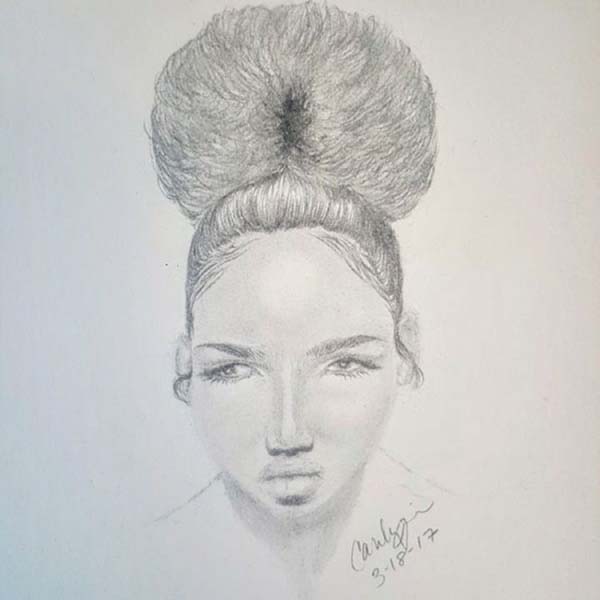

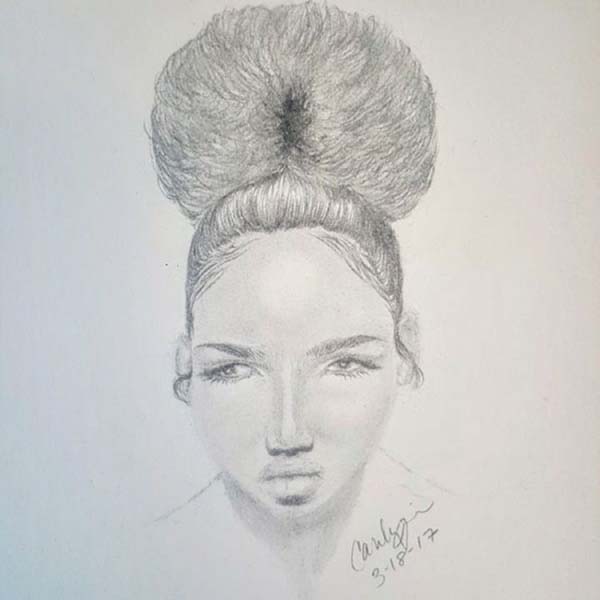

Ticonderoga #2

Clay Carpenter

I always prefer a wooden

pencil to ink. Ink is too

fast, arrogantly denying

its mistakes, believing

it is permanent.

But a pencil is of the

world, cautious and

erasable. Not the

spindly mechanical

model with its

inexcusable fine

shaft of graphite, made

to break, but the

kind that mimics a tree,

thick trunked and

dependable, its life

shortening with the

seasons, notes,

accomplishments,

although it must be

said, the pencil

always outlasts

the eraser.

|

First Strike

Allan Onik

In the Oval Office, The President put out his cigar. “You can come out now,” he said, “I know my detail has been neutralized.” The North Korea Legendary Special Operations Assassins summersaulted out of the passage behind Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Live With.” They wore cybernetic gear with vision enhancements, and carried Type 73 machine guns. The officer pointed a Smith & Wesson model 10.

“Out great leader can’t let you interfere with our glorious nation. We must terminate you.”

The President pressed the speaker phone on his desk.

In the Ryongsong Residence throne room, The Neon Delta X operative retracted his laser blade and disengaged his stealth camo. He slid Un’s severed head into the specimen bag. Body parts and blood splattered the room. He spoke into his ear piece. “Project Big Man has finalized neutralization phase. Entering extraction phase.”

“Affirmative,” The President said, “we’ll prepare for the southern wave at the DMZ.”

In the Oval office, the assassins laid down their weapons. The officer put his Smith & Wesson on the President’s desk and knelt. “Our families are free. Please forgive our intrusion into your lovely home.”

|

Graveyard Shift

Allan Onik

In the breakroom, an employee had fallen asleep in his chair watching a rerun of Hardball with Chris Matthews.

“Do you ever drive around at night? On your day off?” I asked the girl playing with her nametag. It still said “in training” and she’d been working for 9 months. “I almost hit a deer driving to the all-night diner last night. Them sons-a-bitches are everywhere when the hour strikes. And the cops hit the road too—looking for the drug runners and drunk drivers. So, I have to drive the speed limit and watch out for antler wielding flower eaters and pigs.”

“That’s cool,” she said. She popped a stolen sour patch kid into her mouth. “I’m going off to State College at summer’s end. No more red eyes.”

“I already graduated. Cum Laude, baby. The shit.” I took a bite of a stolen banana.

“Well I’m gonna do pre-med and if I get into the med school...”

“You don’t have to lecture me sweet cheeks. I’m gonna hit the best seller list and everything will be fine. Nothing wrong with an English Degree in Steel Town.”

“Yeah. Plenty of demand for dishwashers.”

“Can it. I gotta go scrape the ice off my mom’s car before her shift in the city. It’s dawn, you know?”

|

Just What I Needed

Allan Onik

I curled up on my shrink’s couch chewing Starburst. “Things have gotten a little...different since you started here last year. You’re acting a bit strange.”

“What on Earth are you talking about?!” I asked.

“What do you think has been a little odd?” The doctor began scribbling on his prescription pad.

“When I sprinted through the mall?”

“Yes?”

“When I binged Enya on my CD player?”

“What else?”

“When my grades slipped?”

“And?”

“When I drove 90 in a 30 listening to trance?”

“How about when you told me you wanted to go to Harvard even though you haven’t applied, it’s half way through senior year, and you haven’t won any varsity medals on your crew team?”

“That too, doc.”

“I’m going to recommend you for some medicine. It’s called Risperdal, an antipsychotic. It’s just what you need.”

I stepped outside the office. The holiday snow was falling and the snow on the sidewalk seeped through the holes I cut into my Kung Fu shoes, making my socks get wet. I rattled the pill bottle.

“They will help you to start sleeping better,” my Dad said.

I rested in the back seat as we drove home.

|

The Railway

Allan Onik

Ada looked down at the tracks. In the dusk, the summer fireflies were just beginning to buzz.

“I can’t believe it’s been a whole school year since she left us.”

Tab shifted the toothpick in his mouth. “That bitch Melissa couldn't get over it. Thought she might have been the reason. All that talk on Facebook.”

“I guess when we walk the stones from now on we’ll have to remember. She lives here now. Forever. Until it’s our time too. And then we’ll meet again. I’m sure of it.”

“Forever,” Tab said. The last of the light shined on his face. He dropped the rose on the tracks. The two walked away, hand in hand.

|

Endgame

Allan Onik

In Ryongsong Place, Un watched Jurassic Park in his throne room. The T-Rex was chasing a theme park car down the road. His top general sat next to him.

“You know,” Un said, “it is amazing how long the dinosaurs were the rulers of Earth. For nearly 150 million years they held their reign. They were majestic creatures—far better than us humans. We’ve ruled and lasted for a mere 200,000 years. We are a petty spec in the cosmos. A stain to nature and the other species.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” the general said.

“I know why you’re saying that. Because I hold all the power in this small country. Truth be told, I always found my father and grandfather to be tyrants. So am I. And that is how it will end. That is how the game has changed up to this point. New times and new pressures. And I must live out my role as the so called Great Leader.”

A drop of sweat rolled down the general’s brow. “But you are the Great Leader!” His eyes were empty. He spoke through clenched teeth.

“Put the briefcase on your lap.”

The general followed his orders.

“Open it.”

Inside were three red keys attached to a radio apparatus with wires and blinking lights.

“Initiate Cerberus. Lock on Tokyo, Seoul, and Seattle.”

|

Burn

Nancy Zhang

I got off at 2 AM yesterday. The boss wouldn’t let me leave, telling me I had to finish stacking the damn cans of pork ‘n beans.

I came home exhausted as usual. It wasn’t even much of a home — a dingy apartment filled with cockroaches fit only for a failure. I took comfort in reaching for the familiar location of my old Fender guitar. I found part of the body in an old dumpster one day; I was struck at its decayed beauty, couldn’t get my eyes off of it. I took that piece of junk to my old high school friend, Lennie. He owns a music shop down the street. Said I didn’t have no money to fix it. No problem, he said, I’ll do it for free. Payment for that time you saved my ass in English. Hell, I’ll even throw in your audio cables an’ amps.

And so it was that I became the proud owner of a Fender 1976 Mustang. I wasn’t good at a lot of things, but it turns out I ain’t half bad at this guitar. Picked up a few chords, and suddenly I could strum along some basic lullabies. It’d be nice if I had a kid to play ‘em to, but oh well. I kept practicing and soon enough I got able to play some of that popular music these days. Hey, I thought, might as well make some YouTube videos. Maybe if I’m lucky, I’ll get picked up by some record agency.

I got out my mic and started up the amp. I wasn’t feeling anything too rock-n-roll today, and besides, the neighbors would probably just scream at me. Damn druggies, all of ‘em. In the end, I picked an old Beatles song, “Hey Jude.” It had a nice lovely tempo and wasn’t overly stimulating.

After I uploaded that video, I checked the stats of my old recordings. A couple dozen views at max, but hey all of them were “Likes.” I beamed. In this quiet hour, this moment planted a seed of happiness that spread through my chest. Someone, someone out there watched this video and enjoyed it. And wasn’t that enough?

The next day, I was late to work. Accidentally slept through my alarm and didn’t care enough to rush through morning traffic. The boss was mildly irked, but she let it pass. My boss was an overweight woman in her 40’s with a uniform that looked like it hadn’t been washed in days. Most of the employees frequently showed up late. I suppose they just weren’t paid enough to give a damn. I checked the shift schedule; I was on cashier duty in the morning. That wasn’t so bad. I just had to stand in one place and not piss off the customers. At least I didn’t have to do the heavy lifting like in the evenings. I put on my uniform and took my place in Lane 8.

In the middle of my duty, a pale white lanky teenager appeared in line. He seemed well-adorned, with a classic white blouse and sharp black dress shoes. He unfurled the contents of his shopping bag on the conveyer belt, and a stash of frozen pizza and what appeared to be our entire inventory of soda tumbled out. Probably a damn rich kid going to one of his parties. I was a bit annoyed by his haughty demeanor, but I held my tongue like I usually do. Nothing good ever comes from running your mouth.

“You seem much older than the other workers here.” The lanky teen had the guts to open his trap. “Is our economy that bad that poor old men are forced to work in low-tier retailers?”

I was forced to respond. “No sir, I’ve just been here for a while. Job market’s hard you know. Got this job and needed a place to live is all.”

“Ah, so you chose this place willingly. Poor sod. Why though? With a decent college education, you should be able to land any entry-level professional job. My friend, dumb as rocks I tell you, is an accountant at a local bank. They don’t let him do shit, you know. But he gets paid a decent wage.”

I snarled. “I never get the funds ter go ter college.”

“My, that shows a lack of preparation above all else. If you wanted a quick and dirty job, simply go to a trade school. I hear welders are high in demand.”

His condescending tone whirled around my head, refusing to leave me alone. I was getting increasingly agitated. Who does this kid think he is? “Sir, please, I’m not smart. But I can do some things. I can play the guitar. I’ll be a musician soon, you know.”

“Please!” The teenager chuckled. “I’ve had music lessons all my life. You’re looking at the Tri-state Area Piano Champion for three years running here. You know, I’ve had plenty of electric guitars before. Threw them away. I don’t listen to this trash modern music anyways.”

The quiet flame of rage charged in me until I could hold it in no longer. I had a momentary lapse in reason and threw my fist at the kid’s delicate jawline. It crashed and I could hear a satisfying crunch.

He screamed, his hands plastered on his jaw. All the customers and employees whipped their heads in the direction of the commotion. Boss came running to Lane 8 with a flurry. She apologized profusely to the incoherent teen while panting heavily.

“I’ll habe you sued!”

“I am so sorry about this incident. All of your items are free today. I can get you some coupons for the next year.”

“I don’ care about that! It’s him.” He brandished an accusatory finger at me. “I wan’ ‘im gone!”

“Oh yes, you won’t have to worry about Dylan. He won’t be working for us anymore.”

I started protesting, “But but but, I’ve been here longer than you!”

The boss flashed me a cold stare. Shut up.

After the store manager gave that snobby kid discounts for a year, and everything was settled, my boss pulled me into her office.

“Now what the hell was that stunt you just pulled?”

“I-I don’t know. Sorry. I’m normally not like that, I promise.”

“No buts! If you can’t fucking control your temper with a single asshat, you’re not going to be able to work here.” The boss sighed. “Listen, I know how you feel. I hate it here also. I can’t stand all these damn teenagers. I don’t know what’s gotten into you. You’re normally well behaved.”

“I’m sorry. I don’t know what happened either.”

“Well unfortunately for you, if you don’t have a reason, I’ll have to fire you.” Her eyes warmed up a bit. “Look, I really don’t want to slam you, promise. In fact, I quite enjoy your company. That one time you brought your guitar to work was awesome. Rock on! But I’ve got my own boss to appease. Punching random customers just isn’t good publicity. You know, I got two kids at home and their deadbeat dad is useless piece of shit. I can’t afford to lose this job.”

I hung my head, unable to look her in the eyes.

“Look Dylan, I understand your feelings. Hey, I heard Subway is hiring down the street. I’ll help you get a new job. With time, you’ll be making about as much as you would’ve made here even.”

“That won’t be necessary,” I said softly. Then I promptly rose and left.

I headed to Jimmy’s Bar and Grill after work. It was a good place, except there was no Jimmy and there wasn’t a grill. I suppose the original store shut down and the new owners weren’t creative enough to think of a new name. So now it was just a pub, where the dregs of society gathered in solidarity.

“The usual, please.” I asked the bartender.

“Old Weller Antique on neat, no straw?”

“You got it.”

“Shit taste as usual.” The bartender grabbed the necessary items.

I raised my haunches. “I’m trying to get drunk, not enjoy a fine night.”

He passed me my drink. “You look like shit today. This one’s on the house.”

“Well aren’t you being nice today.” I gulped my cup down, savoring the sweet burn on the back of my throat as the alcohol rushed down.

The bartender bent over the table and leaned in to look me in the eyes. “Say, why haven’t you done it yet?”

“Done what?”

“You’ve got a twenty-two at home, don’tcha? It’s even sawed off for easy storage. No one I know has ever fucked it up with a shotgun.”

I sighed. “I don’t know, really. I’ve always been meaning to, but I thought my videos would take off eventually, you know? That life would get better.”

The bartender shook with a cruel laugh. “Kid, you’re naive. Hell, you’re 37 years old. You’re not even a kid, just a pathetic loser.”

“Thanks for rubbing it in. Another shot, please.”

He poured my cup full again and nearly slammed the bottle on the table. “Say, I’ve got a deal for you. Wanna hear it?”

“Sure. I don’t have anything to offer though.”

At this, the bartender took on a demonic aura. His eyes shone crimson red and his tongue flitted side to side. “You have your soul. I can take that. In fact, I would love it.”

I scoffed. I was drunk enough to play along with this joke.

“Alright sure, what’s in it for me?”

“In exchange,” the bartender said ominously, “You can have any wish you want. All the desires of the world is at your feet. You could wish for riches beyond measure, kingdoms, even immortal life.”

I thought about it for a moment. “You know, I don’t need any of that. What I’ve always known was that I fucked up. I think I just did this whole life thing wrong. I want to redo. I want to do everything over again, except this time I promise I’ll make it right. I’ll take school seriously, I won’t disappoint my parents, and I’ll even get a lover. Please... Just let me do it again.”

The bartender’s dark eyes shone once again. “Your wish is my command,” he hissed.

“Another drink, please.”

#

Robert Smith was having a good day. He had just been promoted at work, resulting in a $10,000 pay increase. His wife, Sharon, decided to make a huge feast to celebrate the happy occasion. She spent the entire afternoon shopping for meat, eggs, an assortment of vegetables, and even a fancy wine. She headed to the local bakery to get the freshest grains. She even took the kids to an that expensive homemade ice cream shop. “Dad’s been given an even bigger responsibility, so you’ll have a lot of expectations to fulfill from now on,” she told them.

Robert Smith was a highly educated man going on his 38th year. He had a degree in Economics from Princeton and went on to get an MBA at Harvard Business School and now was working at a Fortune 500 company making six figures a year. Robert had married his high school sweetheart, Sharon, and the two had a son and daughter. The son excelled at sports and was at the top of his class. Everyone envied little William Smith. Violet Smith was the younger sibling, but he could already tell that she was going to be a beauty. She had delicate blond curls and a natural, rosy complexion. In a few years, he would have to begin warding off a hoard of boys begging for his daughter’s hand.

Robert Smith’s parents beamed with pride whenever they mentioned their son. Oh how they loved to brag about him! “He was always precocious, that one,” they would say. “He always gets his way, that Robert. God truly has given this family His blessings.”

But still, Robert Smith was not a happy man. After he had received an offer from his dream job, Robert found that he was hollow. He had no passions in life beyond beating out his competitors and receiving the higher paycheck. He could not enthusiastically make love to Sharon, seeing her as only a beautiful piece of plastic. It was true, Sharon was stunning. She was a star of the cheerleading squad back in high school, and every woman in the neighborhood was jealous of her spirit and vitality. But he was never able to passionately embrace her. He loved his children, yes, but he was distant. He did not understand what it meant to nurture them, to take care of them.

After dinner and when the kids were all set to bed, Robert confided these thoughts to his wife. She sniffled a little and buried her head deeper inside his chest. She wrapped her lithe arms around his bare skin and caressed his strong back.

“Oh Robert! If only you knew how much you mean to us, how much you mean to me! Don’t worry, I’ve been reading up on this kind of stuff online. I think you’re having one of those midlife crisis. Some of my friends’ husbands have this problem too. I think they’ve had luck with a Dr. Tufas downtown. Oh yes, I’m sure he’d fix you up right quickly.”

“I see...” Robert murmured. “Well Sharon, thank you for the advice. I will make an appointment soon. He softly touched his lips to hers and let the saliva elongate between them as he pulled back. “Good-night, dear.”

Robert checked into the receptionist bright and early. “I’m here for an appointment with Dr. Tufas.”

“Ah yes.” The girl behind the counter spun around. “He’s been having a lot of patients recently. Please sit down in the waiting area, and he’ll come get you when he’s ready.”

At last, an old man with a greying, but still brown beard appeared from behind the door and stepped into the waiting room. He had on a smart corduroy and mahogany pleats. The man looked very comfortable in his business casual get-up. “Mr. Smith?”

“Ah yes, that’s me.”

Robert Smith followed the lightly smiling man into his office. “Please, sit down,” said Dr. Tufas.

“So I understand that you’ve been having depression problems.”

“No — I mean, it’s not depression, it’s just... Well life, you know?”

“No no, Mr. Smith, I understand. This is fairly typical of a person of your age and calibre. I believe your wife Sharon called it a ‘midlife crisis’?”

“Ah, yes, why how did you know?”

His eyes flashed a brilliant red, and he whispered, “Oh, I can tell. I’ve seen a lot of patients like you.”

Dr. Tufas proceeded to ask Robert Smith his usual battery of questions — where he was born, his parents, his experience growing up... Suddenly, Dr. Tufas stopped. He curled his thin lips into a smile, his tongue reaching up and down. “I think I know what the problem is.”

Robert Smith’s heart elated. Oh good, he thought, there’s a clear cut problem, he’ll put me on meds, and I’ll be fixed in no time.

“You don’t have a soul.”

“Excuse me?”

“You heard me right — you don’t possess a soul. You know normally, in this situation, I would exchange a barter. Your life for a wish! But in this case, you have nothing. Not even your own spirit to offer. You’re disgusting.”

“Listen, Dr. Tufas, I’m not here to play games. You know the last time I went to church? Twelve years old.” Suddenly, tears started streaming down Robert Smith’s cheeks. “Doctor, please, just help me.” He started begging. “All my life, I thought I had done things right. I took my education seriously, I got a good job, I got a wife and kids, my parents love me... So why then... Why can’t I be happy?”

At this point, full-fledged droplets were streaking down Robert’s face. He became unable to contain himself. “I-I’m sorry for showing you this mockery of myself. Why, the last time this happened was years ago.”

Once again, Dr. Tufas’ eyes slitted and shone blood red. “I’m sorry Mr. Smith, but without a soul there’s nothing I can do for you. Except, pray for your salvation perhaps.” Dr. Tufas laughed cynically.

“It’s okay, I understand.” Robert Smith left the clinic with his eyes glazed over and his shoulders slumped.

On his way back home, Robert stumbled upon a dumpster. Normally, he would have grimaced at such unsightly things, but today, for some inexplicable reason, he was drawn towards that grimy green metal cage. He inched closer and found the decaying corpse of a 1976 Fender.

Truth be told, Robert was always a guitar nerd. Ever since he was little, he liked to play loud rock music. Unfortunately, his mother advised him that that was unbecoming of a young gentleman, referring him to the more classical piano. However, Robert would always grab guitar magazines and ooze over all the different makes and models in secret, waiting for the day that he could play his own instrument.

Robert grabbed the guitar and wiped as much dirt off of it as he could. There was still life in the instrument, Robert decided. He knew a guy, Lennie. Owned a music store down the street. Real nice guy. He could fix the guitar right up. Maybe throw in a free amp and audio cords as well. Robert got to work.

|

Mature Demolition

John Zedolik

Death to disco and its wax

remains, he determined in ‘81

so firecrackered the small batch

of 45s from ’77, ’78, and ’79,

speeding the shards into futile

skies, disposing of the dross

from those insipid years

as he followed the current trend

to which at 15 he was expert—

of course—unlike three years

before when he simply—a pure

child—enjoyed the now worst

|

Accept Apart

John Zedolik

Resist the urge to hate the art

of the artist who was a

bastardpervertcriminal

just because you hate him/her

and cannot stand giving credit

to one so objectionable to your/our

sense that right life must marry

right art and dance the distance

in harmonious steps, one leading

then alternating to the other and back.

You must separate one from the other.

Influence is certain, but these two

are not necessarily paired. Let go

of the miscreant, the mad, the cad

and let art swing—up, away, and out.

|

Mute

John Zedolik

Could only imagine a spinal column

drifting down, blown free from its flesh,

onto the standard-issue tent

as the ex-soldier told me

could only imagine the bone-assemblage,

like an untethered wind chime,

clumping, unmusical, on that fabric

torn by the blast

as the ex-soldier saw

and hoped never to, again

even as he made the vision,

just one time, clear to me

|

Flames over Anacostia Flats

Lee Conrad

Patrick O’Brien stepped out of the slapped together shack on the Anacostia Flats. The July morning was already hot and steamy. The Flats, situated between Washington DC and the Anacostia River, muddy even in dry times, added to his misery. His denims and cotton shirt, loose on his wiry body, were soiled and sweat seeped through. He looked around the encampment as the 10,000 strong remnants of the Bonus Army in their make shift city called Camp Marks roused from an uneasy slumber.

O’Brien, like the rest, was a veteran of the Great War. They came to Washington DC a month ago from all over the country to pressure congress to give them the veteran bonus that was due to them. It was two years into the depression and people were desperate. They were out of work, out of their homes and out of hope, except for the promise of the bonus. The bonus though wasn’t payable until 1945, and now in 1932, many felt they would be dead from hunger if they waited much longer. They wanted the money now and the Bonus Army and its leaders came here to make sure they got it.

“Hey Patrick, want some corn mush? It ain’t much but it is tasty. Might cheer you up some.”

The voice was his friend Sean Ryan. They served and fought together with the 1st infantry in France and survived. Many of their comrades didn’t.

“Thanks. Don’t give me too much. I don’t want to short you.”

“When we get our bonus you can buy me a fine meal at a fancy restaurant,” said Sean.

“You know Sean, this congress and this President Hoover ain’t going to give us anything. You have been out of work for a year and I’ve been looking for work for a year and a half. The “good citizens” of those towns we passed through on the way here called us tramps and bums. They didn’t call us tramps when we marched off to war in 1917.”

“Patrick, when the Senate voted not to give us the money in June I thought it was all over. But look around you. Even though many have left there are still thousands here in our own Hooverville and more inside DC. How can they ignore us?”

“We and the thousands of others are here because we got no homes to go back to Sean, and they will ignore us or worse.”

They finished their corn mush, cleaned up and walked towards the center of the camp.

Camp Marks was orderly, with streets laid out like a regular city. Kitchens were set up to feed people, even though the food donations were running out. A library was set up by the Salvation Army. At night bands would play music and the people would dance their cares away. The dwellings of the people were everything from scraps of wood and metal found at the rubbish dump nearby to canvas tarps and tents. Some even built small replicas of the homes they no longer had. Signs on the shacks showed where they were from. “Racine, Wisconsin to DC!” said one. Another said “Washington or Bust-Bonus We Trust”. Still others flew state flags and American flags. This was their city and their country.

The people looked like the millions that were out of work and living in tent cities all across the country. Gaunt, sallow faces from too little food and too much worry. Veterans who brought their families looked worse off. Their children had distended bellies and no shoes. Mothers kept clothes together with scraps of sack cloth. White and black veterans shared food and dwellings. The segregation in the military and even in their home states was ignored here. They all had a common purpose and it kept them going.

“Hey Sean, seems to be a gathering over there. Let’s see what is going on.”

On the back of a truck a leader of the Bonus Army was speaking.

“Men, you have a right to lobby congress just as much as a corporation or those corrupt Wall Street bankers. Let us march, but keep your sense of humor and don’t do anything to cause the public to turn against us.”

With that he jumped down and mingled with the other veterans as they all began to head to a small drawbridge that led to the capital district. Sean and Patrick joined them as the mass of people chanted “the yanks are starving, the yanks are starving!”

Thousands of veterans were also camped inside Washington. They had taken over the many abandoned buildings that were all over the capital. There was an uneasy peace between them and the police. The Chief of Police was a veteran and sympathized with their plight.

President Hoover and Attorney General Mitchell did not. They considered the ex-soldiers a ‘communist mob’ who illegally occupied the nation’s capital. They gave the order to clear out the veterans.

By the time the thousands from Camp Marks made it to the capital district the police were on the move. Buildings were being cleared out of veterans.

Patrick and Sean watched with dismay as police stormed an abandoned building filled with veterans.

“Sean, did you hear gun shots?”

Veterans poured out of the building.

“They killed two of our fellows,” yelled one.

“I didn’t survive the war to get shot here. Bill Hushka and Eric Carlson were both shot dead. Now the poor bastards will get their bonus,” a disheveled vet said to Patrick as he passed by him.

The two friends nodded their heads in understanding. The bonus was paid early on one condition, if you were dead.

The police pushed the ex-soldiers away from the abandoned buildings and towards a line of trees along Pennsylvania Ave.

At 4:45 pm as veterans mingled with government employees leaving work, 400 soldiers and 200 cavalry with 8 small tanks behind them moved down Pennsylvania Ave. Off to the side was Army Chief of Staff General McArthur.

McArthur walked over to a cavalry officer. “Major Patton, I want you to clear these red insurrectionists out of this city.”

“Yes sir!” he said. Major Patton wheeled his horse around and led his troops towards the crowd of office workers and veterans.

The veterans thought the military display was to honor them as ex-soldiers of the Great War. They cheered them as they approached.

Suddenly Patton’s cavalry drew their sabers and charged veterans and government workers alike. “Shame, shame” echoed from the scattering crowd.

“Come on Sean, let’s get the hell out of here. Head back to the camp.”

Soldiers wearing gas masks and with fixed bayonets on their rifles threw tear gas canisters at veterans and onlookers alike. The vets, having tasted war before, threw the gas canisters back and fought with whatever they could pick up.

“Sean, we went through worse than this in the war. Remember your training and we will get through ok,” said Patrick, barely able to talk as he choked and coughed on the gas.

“Patrick, they are coming this way,” yelled Sean.

A soldier in a gas mask advanced through the haze of gas and lunged at Patrick with his bayonet. Patrick’s mind was now in 1918 France, not 1932 Washington and he reacted with force. The soldier in front of him was the enemy and Patrick side stepped and took him down easily. As the soldier lay on the ground, Patrick’s clouded mind reached over for a large rock, held it above his head with two hands and prepared to smash the gas masked face in.

“No, Patrick!” shouted Sean above the din of shouts and horses charging.

Patrick shook his head and his mind cleared. He ripped off the gas mask of the prone soldier. In front of him lay a soldier with a young face.

“Sweet Jesus boy, how old are you, 12?” said Patrick.

“No, I am 18,” said the soldier with contempt.

“Right lad, and when we were in France fighting, you were in shorts hanging on to your Mama’s knee. Now stay there. Don’t follow us. And maybe you should be thinking you are on the wrong side in this fight”, said Patrick as he moved away.

Sean glared at the young soldier. “You’re lucky we don’t have guns. I guarantee I am a better shot than most of you.” With that he turned and joined Patrick and other vets making their way back to the vet’s city.

The trek back was a battle in itself. Hundreds of veterans fought back as cavalry slashed at them with their sabers and soldiers jabbed at them with bayonets. Tear gas wafted over the area, burning faces and searing lungs

Off to the side Sean saw a soldier bayonet a black vet in the back. He walked quickly over to the injured man with Patrick close behind. As Sean knelt down to help the injured man the vet said “go on suh’s, just leave me.”

“We aren’t doing that, are we Patrick,” he said looking over to his friend who was eyeball to gas mask with the soldier. “We were in it together over there and we are in it together here.”

With that they helped him to his feet and took him to a group that was taking care of the injured. They sat him down. He winced with pain. “Thank you fella’s,” he said. A vet next to him coughed violently. “Gassed at the Argonne and gassed in Washington. Don’t that beat all,” he said as another coughing spasm shook his body.

They left the wounded in the care of an ex-battlefield medic and joined the routed vets making their way to Camp Marks. When they reached the drawbridge to the flats they looked back at the carnage and mayhem taking place. They couldn’t believe that soldiers had attacked ex-soldiers in the nation’s capital.

General McArthur stood at the drawbridge leading to Camp Marks, hands on his hips and chin thrust in the air. He yelled out to an officer in charge of a detachment of soldiers, “clear them out!”

Soldiers moved into the camp with bayonets and torches. One by one they lit shacks and tents on fire. Scraps of wood, possessions, flags and the homemade signs of the Bonus Army lit up the darkening sky. The books in the Salvation Army library added to the conflagration. Families were forced out of their pitiful dwellings, barely retrieving the little possessions they had.

As the flames rose above Anacostia Flats the camp looked like hell on earth—a nightmare come to life.

Patrick and Sean moved through the camp, helped people when they could, but knew they had to get out the back way.

Panicked thousands, some in cars, many on foot, once again moved as one.

When they reached the outskirts of Anacostia Flats, Patrick and Sean looked back at the flames that rose above Camp Marks. Shacks were burnt to the ground, as well as the possessions of people who came to Washington with the hope that someone would listen to their plight. Smoke billowed towards the capital district. There was a curtain of blackness between the capital and the veteran’s city.

“Well, Patrick where to now?” said Sean wearily.

“Outta here. And I don’t think we will be getting our bonus,” said Patrick angrily. “This was the last straw for me. It was bad enough they killed the economy and our jobs. Now they want to kill us. If that is what they do to veterans who just want what is owed them, what are they going to do to the rest of the country? I think what I will do is put one foot in front of the other and where I go I will tell people what I saw happen here today.”

“If you don’t mind, I will tag along with you. After all I got nowhere else to go right?”

The two friends turned their backs on the capital district, leaving flames, tear gas and chaos behind. They joined the dispossessed veterans and their families, a stream of refugees in a country lost and adrift.

|

SniperGale Acuff

I’m about to pull the trigger that kills

my father. I’m three years old. He’s sitting

in his easy chair in the corner of

the living room. It’s Christmas morning. One

of my presents is a toy rifle which

clicks when I pull the trigger. No ammo

with it, though, so I improvise: I jam

a short green Tinkertoy stick into it

and, on a long diagonal across

the room, I aim at him, aim carefully,

because he’s wearing glasses, and a corner

of the newspaper wafts with the warm breeze

from the steam heater against his wall. I

don’t know what I’m doing and nobody

ever taught me to shoot and I don’t know

why I’m bearing down on him but then I

fire and the Tinkertoy catches him right

below the right eye. This is my first time

shooting with a real projectile, though I

don’t know that word yet. I do know hungry,

thirsty, sleepy. I know what anger is.

I know the body language, though I don’t

know what body language means, of my hand

on my fly, trying to choke off the pee.

I know please and thank you but I don’t say them.

When my plate’s empty and I want more I

scream Meat! or Potatoes! or French fries! though

they’re curing me of that. Pass them pork chops,

I might say. I wan’ mo’ red stuff, I’ll say.

Sauce, I mean, but I don’t remember that.

Milk I know. Water. Kool-Aid. Ice cream. Pie.

Cake. Cookies. Candy bar. My c is bad

—Take. Tookie. Tandy. Sometimes I get them,

sometimes I don’t. When I don’t, look alive.

I never fired a gun before without

my mouth blasting the appropriate sound,

accompaniment for people I’ve clipped

—sisters, brother, mother, grandmother, dog,

cat, goldfish, invisible (but I see

them) soldiers, Indians, aliens, thieves.

Sometimes Pow. Then there’s Bam, Blam, Kapow, Boom,

Ping-ping-ping, rat-a-tat, rat-a-tat-tat,

and other sounds even grownups can’t spell.

And when I’m dead I always rise again,

if not as the same person then one life.

No one can touch me even if they do.

Except for being spanked—that makes me mad,

I cry and crying makes me furious.

They lock me away. Sleep it off, they say.

I lie there and make plans and sniffle and

choke my teddy bear ‘til his rubber nose

and jowls protrude and scare me then I hurl

him against the wall and leap on him where

he’s landed, my boots on his stupid face

which never breaks expression unless I

force it and then (except for one crack where

I stabbed him with a flathead screwdriver)

it always pops back into shape. I hate

that—he’s cuter than I am and will out

-last me. Father puts the news down, rises,

pads past me like I’m one of those zombies on

Saturday afternoon TV movies

I’m not allowed to watch. I follow him

into the kitchen. I have learned to say

I’m sorry then, without being told to.

I’m thorry, Daddy, I cry. I dint

mean it. He’s bathing his eye at the sink.

You not crying, is you, Daddy? He says,

It’ll be alright, Son. He doesn’t

hit me. He doesn’t lecture me. What’s more,

he doesn’t take my Christmas gun away.

He just returns to his chair and paper

and crosses his right leg over his left

but it’s usually left over right

so maybe he’s just protecting his whizzer

from me in case I should try to outdo

myself. I’ve killed him—that must be his ghost

sitting there. I’m not sure who’s won. I feel

cheated. It isn’t fair. I wouldn’t be

happy with him dead but living kills me.

|

Sunday

Neil Flory

The carpet

is dirty and so is the stove and I could really

stand to do something about this sink

full of dishes not to mention the leaky faucet gadzooks

who knows what other untold projects I could

scare up but ah forget it I’m gonna

drive out into the hills watch the hawks glide

back and forth all day long high above the river and

there are plenty of cemeteries that I don’t

listen to and perhaps that’s what

keeps me just afloat

|

they’ve run out of wine at the market

Neil Flory

job listings today?

not even one, his reply.

hand me the vodka

|

What’s it Like to Be An Addict?

Marc McMahon

Do you remember what it was like when you were about 14 years old let’s say and you wanted to go do something that was forbidden by your parents? When you would weigh the benefits of sneaking out to go to a party vs. the ass whooping your Father was going to give you if he finds out. When you get that nervous excited feeling in your stomach that says I’m going to do this anyways even though I know I am going to get caught and severely punished.

That uncertain, empty, gut knotted tighter than the best double knot you ever tied as a little boy feeling that you get, when your mom finds out you stole the rent money out of her purse and sent you to your room to wait hours until your Dad got home from work to deal with you! When your only means of escaping the inevitable is to fill a backpack with your most prized personal possessions and run away from home.

But then you realize if you do decide to flee for your life, your Father will hunt you down like a wild game animal. Gut, skin, and hang you upside down from a neck hook so you can bleed out before slaughter! That all too familiar fear that grows infinitely stronger with each passing moment. Building up to the point where as soon as your Father opens your bedroom door, you will be consumed with an overwhelming, heart-pounding fear, that causes you to break down into a terrified whimper as soon as you see his face.

An all too familiar feeling that my addict behavior has allowed me to, unfortunately, become as used to as one possibly can. Like being put in a dimly lit room with your killer and hearing the door slam closeed behind you! It is fearful, frightful and fun-filled. Serious, selfish, and surprising. Hateful, happy, hurtful, and high. It is everything you ever wanted and all the things you prayed you would never get all ground together into one big, exhausting nightmare!

Being an addict goes well beyond the scope of having a bad habit that you might indulge in a little too often. Being a bottom of the barrel, gutter level, under the bridge sleeping dope fiend is a way of life. Not one you would have ever chosen mind you, not even one you would wish on your worse enemy. But one that was forced upon you to master by the very disease you have chosen to embrace.

We chose to recreationally get high at some point in our lives just like millions of others do for the first time every year. For most the substance use serves its purpose, runs its course, and the casual user will eventually grow out of it as life’s pressures to perform begin to out way the benefits of doing the drug. Or the negative consequences experienced begin to out way the benefits of getting high.

But for some, like me, the drug we decided to play around with for fun at some point decided to flip the script on us. As it decides to use us for some fun of its own. There is an old saying that goes “see the man use the needle, watch the needle use the man!” And as we at some point choose to try and fight this monster that’s within us a lot of us begin the arduous journey of trying to get clean & sober. It is for many a vicious cycle of recovery and relapse for years for some before they ever gain any long-term sobriety.

Once a person gains the upper hand on their disease though I believe that they have through that experience acquired a strength of character almost unrivaled by any other. It gives civilians a combat experience known by few, and it teaches us how to survive some deplorable situations. It is a ride that many get on and only a few get off. A roller coaster of monstrous magnitude that keeps twisting and turning your entire being. Rendering you a shell of a person who wanders about wanting help but being too ashamed and afraid to ask.

|

Falling Upward

Marlon Jackson

Moving forward is sometimes a challenge.

When obstacles plop down way past average.

I see the sun ablaze, but beneath I get lost

sometimes where I’m coming from.

The moonlight follows me at night and I see

the shadows that keep me up all night.

They run and they lurk within the area and within

and upon my presence.

They irk me as I walk around and slow my speed

I bend and i continue because it’s my destiny.

|

Founders’ Day

Logan Lane

I’m living in the era of S women: the Saras, Stephanies, Samanthas, Selenas, and Syndneys. Sometimes even Sierras or Stellas. We don’t get a lot of Sadies, Syklars, or Savannahs in Northeast Ohio, but when I find one, she’s always a ride.

I met a Sage, once, too, in the alright part of Akron: a little strip of bars and muraled coffee shops. She had strawberry blonde hair and eyes so dark they swallowed the light. When we were drunk enough, I asked her to fuck me like a prophet. She did.

It could be just a quirk, an oddball fetish—but I think it’s more than that. I like to believe it’s something in the rhythm and noise between people, something between the syllables of the names. The way the whole package rolls off the tongue. Something in the brain, in the heart and loins, recognizing a familiar spark. It could be romantic; sometimes it is.

Just now, I hear Sabrina downstairs in the kitchen. The blender growling. A window opening. Warm air rolling indoors. Her sneakers on the linoleum. I roll over in bed and smell the hint of her perfume on the pillow beside mine. All of it holds a trace of the name, just a whisper of the person running around downstairs. Even the home noises, the creaks and cracks, that she makes underfoot carry a dash of Sabrina.

I’d think about it more, but it’s Founders’ Day. That doesn’t mean much, but here in Akron it’s when the alcoholics and their sponsors and their families and their knobby little kids go bumbling around the city. They jaw around on street corners and in little diners between AA landmarks, talking about the wonderful thing Dr. Bob and Bill W. created some years ago. And always by midday they flock to Dr. Bob’s very own house, the little white two-story across from the apartment Sabrina and I share.

So, right now, instead of thinking about Sabrina, tasting her name in my mouth, tasting her, I’m watching a herd of American suburbia and grimy bikers mingle on Dr. Bob’s lawn from our upstairs window. Soft, stooped men in high white socks, ball caps tugged over their grey heads, loose polos and t-shirts smacking around in the breeze. Others in black boots and jeans, their shirts unsleeved at the shoulder. They mill around Dr. Bob’s yard and on the sidewalk, aimlessly pointing, laughing, nodding, smoking.

Sabrina calls from downstairs.

I go down. She’s made lunch: two bowls of tabbouleh quinoa salad. I’m not surprised to find that she’s already eaten hers. I sit down and she stands, swings over to the sink to clean her bowl. In running shorts and tennis shoes, with her hair pulled back into a tail, she is a cord of muscle and tight tan. She’s listening to music in her earbuds. She sort of sways and bounces, kicking the rhythm around, and I hunt the beat springing down her thighs as she steps her weight from one foot to the other.

“Hey,” I tell her.

She hums hello.

Watching her, I know she’s already taken her pre-workout. She eats the powder like my dad used to eat cocaine. She mixes it into her cereal, her salad, her smoothies. When it settles into her system, her eyes go quick and ardent. She gets a warm, sweet flush across her neck and chest. It makes me sweat. For a while, I watch her at the sink. She attacks the dry bits of quinoa in her bowl with a brush. She bobs her head, stamps her heels into the floor mat. Her body is a spring, and all I want to do is throw myself against it.

Eventually, I stand and slip behind her. I push my hands across the curve of her waist, down past the navel, under the waistband of the running shorts. I reach the holy land and she pulses back into me—receptive, I think—until I start kissing her neck.

“Jack,” she hums, shrugging me back.

“Sabrina.” God, her name is candy.

“I’m going for a run.”

I cling to her, pleading with kisses and sighs. She whips around, snatches me by the shirt, kisses me. She dives down into my tongue. Her skin buzzes; her heart gallops against me. I could climb into her, make a throne out of her surging ventricles. Or not. I’d be happy to beg between her legs.

“I’ll be back in a bit, alright?” she says finally.

“Mhm.”

I watch her leave. I consider, for a moment, going back upstairs to stand at my window and track her down the road—not to scratch some neurotic itch, but just to carry the flows and flutters of her body with me for a while longer. I know that a bit could mean two hours, three, or even longer. During summer weekends, when Sabrina works out three or four times a day, I see her in blurs and flashes, hear her in fits and creaks. The dark tail of hair bobbing behind her as she pushes open the door. A waft of her warm, working body as she goes up to bathe. The squeak of her sneakers. The gurgle of her blender in the kitchen. Our interactions, brief exchanges in the kitchen or in the bedroom, always leave me stirred.

After I finish eating, Sabrina texts me gym and I can already see and feel the day and evening unraveling, their transition completely void of her. Often when she runs, she’ll decide to step inside the nearest gym. She comes home, hours later, flushed and ragged, panting like a horse, and passes out before I can even kiss her hello.

It’s been happening more often lately, too. Our interactions seem like haphazard collisions, our conversations like static. Love babble. Crooning laughter. Updates on each other’s professional lives. The fate of mutual friends, of our local siblings and parents. We pick and prune our future plans, the vacations and getaways that are half-trimmed, unwatered. Maybe it’s all normal. Maybe there’s nothing wrong with what’s happening. Maybe this is what happens when we grow accustomed to the rhythm of our partner’s routines. Your joined life just goes subsonic. A fall into white noise.

I wouldn’t mind so much if it didn’t seem like our sex were not also just another nameless mutter in all of this low, cold noise. Momentary contact when it’s convenient. Brief and fanatic collisions before we succumb to sleep and, in the morning, Sabrina races off again.

Six o’clock comes by and I decide—no, I realize—that I need to go out. I text Sabrina that I’m meeting a coworker for dinner. When I step outside, the city and all of its crowded heat and noise boils around me. Men in black tank tops roar by on motorcycles. The alcoholics and company, still milling around Dr. Bob’s house, wave at the passing bikers. I go out into the street and unlock my car.

“Hey,” a man calls out as I’m fishing my keys out.

“What?”

“How’s it feel living next to Dr. Bob?”

I shrug. “Like living next to any other dead doctor, I guess.”

He laughs furiously. His gut sags and swells. All 210 pounds of his sweaty, good-natured gymnasium bulk goes ruddy. “Yeah right, buddy. You know what he did, right? Dr. Bob, I mean. The man’s a hero.”

“Didn’t he spend seventeen years performing surgery while drunk out of his gourd?”

Everything good and whole about this middle-aged, pink-cheeked man goes sour. He looks at me like I’m small and insignificant. “He founded AA,” he says. “You really should be more respectful.”

“But he did that after, right? After all of his operations, I mean.”

The man shakes his head and returns to his family across the street, a wife and child who give Dr. Bob’s home long, craning looks. I climb into my car and swing onto Main Street and find myself in a pack of motorcycles, engines ripping and growling. I drive to the strip of bars and cafés.

I find a bar, some place out of the way, but it’s still early. I find a place and have one beer, two, and then start scoping out the place as the sun comes down. People start filling the bar, packing the walls with a warm, rowdy buzz. They bob to the pop music, laugh and babble. I look hard for an S. Eventually I spot some woman in jeans and a T-shirt drinking a beer a way down the bar. She’s not gorgeous, but her body’s got enough swerve to rope me in.

I go up alongside her. We start talking, going through the rhythms. She’s an engineer somewhere, a dog-lover, an avid fan of Spanish culture. Celine, she tells me. Not an S, but it scratches the itch. I buy us another round, and we’re both getting tipsy, and then some, and we get closer, thigh-on-thigh, cooing amours in a raw, wanting whisper.

I’m half-aware, this whole time, of a flock of women a few feet away. They chatter and laugh, but there’s one, a dark-haired thing in tight jeans, the queen of the flock, who keeps telling her friends how ironic it is that we’re all here, in a bar, on Dr. Bob’s very own day. Isn’t it just so ironic, she says? Isn’t it just the epitome of irony that there are still happy hours on this of all days?

But even that melts into the background static as Celine and I start getting warmer. We bounce and roll to the wobbly throb of some pop song. We slop back the rest of our drinks and I lean in, give her the eyes, ask her if she’s got a place nearby. By now, we’re both hopelessly athirst, draped over one another, murmuring nonsense while our bodies do the work. This is my favorite part. Always. It’s like the tide starts to roll. It washes the place out, makes all its noise fuzzy and distant. We’re trapped in our own pocket of acoustics, caught up in our own buzz and babble. We’re elbowing people around us, catching eyes from the tenders and wallflowers. My hands are antsy around her waistline; hers are having a tantrum against my belt buckle. I start pushing toward the door when I hear the woman again, the queen, keening in my direction:

“Jack? What the fuck are you doing?”

Now, even a bit slurred I can hear my death knell in queenie’s voice. I consider shoving the catch, my Celine, forward, onward, out into the hot night. I consider bolting alone. But before I do anything, queenie catches up and sinks her claws into me.

“Jack, who is this? What’re you doing here?”

I turn around and get one look to confirm. It’s Sabrina’s sister. She comes at me with those eyes, pupils leaping up at me. I’m not completely shameless, so I mount a quick defense. I’m stupid, I tell her. Drunk, too. Stupid and drunk, out of my depth. I abandon poor Celine. She leaves scowling at me, swearing at me, as I stand packed in by queenie and company, hounded by promises of retribution.

In the end, none of it matters much. I escape—wading through the tide of shoulders and arms—while queenie is calling Sabrina. I push open the doors and stream out into the hot, wooly night. I bum a cigarette off some guy outside just to spite my body, my brain, my lungs. I choke it down and go along the street, trying to unscramble my head. I’m usually careful, cautious, but I’m not much of a planner. It’s all starting to go loose, to unravel, and I think, shit, let’s just ride it out.

So I head to the next bar. I’m walking along when I see this tall, filthy, yeti-limbed caveman come shambling down the sidewalk. Ragged, dirty, bearded, he’s almost Paleolithic. He hugs the curb, weaving in and out of the parking meters. I slow down to watch him. He stops alongside each one, hugs his hand against the meter head, and feeds a plastic card into the mouth of the machine. It’s late, so I know those meters aren’t ticking, but he works them like a meter maid—no, like a dancer, a lover. One step, two step. Card in, card out. One step, two step. He swivels, snatches the next head, feeds it the plastic. It’s marvelous. A heavy madman working his meters in two-time.

But wait—he’s got a snag. The machine eats the card, spits it back out, but the yeti doesn’t move on. I expect him to freak, but instead he goes in close, starts murmuring to the machine. He smacks his words around in his mouth, slops them across his tongue. I can’t make it out. For a second, I really think someone’s pulled him out of a museum.

Still slurry, I go in close. I can’t catch a look at the meter, so I go in real close. I’m lover-close now, and the yeti doesn’t smell as bad as I’d thought. No boiling rot here; just a sharp, musky zest lurking under dry mildew. A real complexity.

“Hey, buddy,” I call out.

He starts jamming the card in and out of the meter. When I crane a bit closer, I see the ERROR on the machine’s screen. It flashes this message and gives a digital whine each time the man rams the card back in.

“I don’t think it’s working.”

One, two, flash, whine.

“It’s not working, man. Give it a rest. They don’t even run after eight anyway, so I’d save the charity until tomorrow—if that’s what you’re after.”

I’m about ready to turn tail and leave the man, but I finally make out what he’s saying:

“Nineteen-seventy minus eighteen cents, then another fifteen. We get—mm—we get—aahh—we get thirty-seven. Mhhh-yuh.” But it’s all low, garbled, dragged through the gutters of his poor mind. So I shove my palm over the error message, grab him by the wrist. I feel his sharp bones and tight little sinews twitch in panic.

“Easy, easy. Just wait. It’s Founders’ Day, you know? It means you don’t gotta do this, buddy. Here. Don’t look, don’t listen. Just feed it one more time, yeah? This one’s on me, though. Don’t worry about the money.”

The yeti doesn’t give me his eyes—they’re lost somewhere out in the dark—but he manages to jerk a nod and give the machine one more two-time. I even cover the sound grate so he can’t hear it whine. I think Dr. Bob would be proud.

He turns away and shambles on down the sidewalk. I want to turn around and keep walking, but I’m stuck. I just stand there and stare at him, at this shaggy madman, and just before he disappears into the dark, I see him start lurching back toward the meters.

I manage to swivel back around, but after a minute of walking I too start to lurch. I nearly run into the bouncers outside the first bar I come across, and they almost don’t let me in. But they do. I get inside. I have one drink, then another, and then some liquor. I get sloppy with booze and cigarettes. The noise here is bad, spoiled. I can’t tell an S from a T. Hell, I can barely give the barman my next order—but I’m set on seeing this thing through. By the time I roll out of there, I’m stumbling, pawing at my gut, slurring through names.

Shelly, Shelia.

I chamber each one, let it sit on my tongue, but they don’t feel right. What was her name again? The number in the jeans?

The night and lights and cars swing past in streaks, the colors starting to run. I look up and find I’m no longer even on the sidewalk. My leg catches on a tangle of bush. I go tumbling. For a moment, I thash around in the growth, trying to free my limbs. Then I’m out. I get up and haul myself across the street—my street, I realize, as I kick leaves and twigs out of my jeans.

Stephanie, Suzanne...

Down the road, Dr. Bob’s porch light is on.

Shelby, Sara...

The bikers stand smoking on Dr. Bob’s lawn. They watch me, heads cocked. I cross the street, still spilling names, and climb my own porch. But I stop and hang there on the porch. I swing around and take a look at Dr. Bob’s, at the bikers there, and consider wandering over. I could just walk right over. I could shoot the shit with them. Let the night unwind. Ride this thing out. I bet they’d let me stay if I said something nice about Dr. Bob. I could tell them I helped a homeless man. They’d love that. They’d probably let me hunker down and sleep this off. Maybe afterward, I could remember the S from the bar. Her name is still buzzing around somewhere.

I wrestle with this mess, try to force it into shape, until my own porch light whines on above my head. I blink the light out of my eyes and when I finally swivel around, Sabrina’s standing there in the doorway. She’s in her bouncy running shorts and her hair is pulled back into a bun. Her eyes are tight and red and misty. She doesn’t look at me, won’t look at me.

“Sabrina,” I slur.

She swerves around me, her sneakers squeaking on the sill, and dashes out into the night. And I really can’t bring myself to chase her.

|

Sleep Again

Gregory K. Eckert

2005—

I cannot honestly say why I did what I did. I’d like to think that we all—at some point in our cowardly existence—have elected to push instead of pull—or watch instead of act. We are, after all, incredibly emotional, and because of that fact, irrevocably flawed and inherently weak. If you’re viewed as a strong individual, it’s because you haven’t been watched long enough. Do you think that philanthropy is about giving? No. Hell, no. It’s how the rich absolve all that prevents the pillow from doing its job. If enough newspapers tell you you’re a good person, you’ll start to think it’s true—you’ll celebrate the person that money can buy.

But that’s not what you’re here for. You need the whole story, and I will give it to you—the unadulterated version.

——————

Jan 1992———

The first time—and the last time—I walked into his apartment, there was a haze of cigarette smoke spread across the living room and two faded sofas stretched along adjacent walls. An all-glass chandelier hung directly above the kitchen table—massive in size—and emitting a hazy, inordinate amount of light throughout the first floor. To the left of the front door was a closet. The door was taken off its hinges, propped against the wall just before the steps to the second floor. This closet was overflowing with all colors of dirty clothing; board games were stacked haphazardly on the shelf at the top. A damp odor traveled from the closet. Jeremy clomped his way down the steps with a smile on his face and untied shoelaces swinging through the air like unburdened wind chimes.

My parents were always fine with Jeremy visiting our house, but they didn’t want me anywhere near his. My mom would be doing dishes in the kitchen and would call me over to her. “Cops over at Jeremy’s house—again,” she would balk, scrubbing an oven pan, directing my eyes out of the window with her glare. “I wonder who the center of attention is tonight. My guess is that little slut Mary.”

Her questions were, no doubt, rhetorical. Engaging my mother in battle is just something you don’t do. If you’re not with her, you are immediately in her crosshairs. Her words sought out anyone that elected a different lifestyle than her own. Jeremy, of course, according to her, did not choose his life. That’s how she arrived at the “he can visit here, but you cannot visit there” mentality. She thought that he was nice enough, always sporting a doltish smile and wearing dirty, second-hand clothing—

“Let’s go before my dad wakes up,” Jeremy said quickly. “He was in a bad mood last night.”

I shook my head and turned around and reached for the doorknob. Twisting and pulling, I couldn’t seem to get the door open. I turned the main lock back and forth, hearing the bolt awkwardly click as I struggled.

“You have to lift up and pull real hard,” Jeremy interrupted, while I played tug of war with the door.

Jeremy walked up beside me, slipped his right glove off and opened the door in one fluid, jerking motion. He motioned for me to go first, but then raced out the door laughing, playfully elbowing me out of the way as he ran into the arms of the cold winter wind. He quickly turned his head around and smirked at me. Jeremy licked his lips and used his fingertips to tuck his dark curly hair under his flap cap. He smiled and his eyes narrowed tightly below his thick black eyebrows. The lightness of his skin drew comparisons only to the fresh snow falling sideways all around him.

Dusk comes early in January. The temperature plummeted as the sun tucked behind the massive box elders that lined the western end of town. The icicles enveloped the branches, absorbing the last bit of sunlight trickling through the tiny spaces between. Jeremy sprinted ahead like an animal set free. I didn’t chase after him. I never chased after him. The truth is Jeremy is what I called a neighborhood fringe-friend. He helped me pass the time, but at school, I ignored him. We are not the same. Jeremy is simple.

I see him take a seat on the lip of the underground sewer drain that protrudes out of the ground near where the cornfield and edge of town meet. Close to the edge of our neighborhood is an above ground sewer tunnel. For two years we’ve had a competition to see how long you could stay inside without coming out. It seems to go for miles like an underground maze, occasionally providing a sewer grate where you could look up and see some other part of town. Before today, the record had been three hours and twelve minutes—set by me just last month. A few of the neighborhood kids say they broke my record, but not a single person has someone to back them up, someone to claim that it was true. I had just the light from my watch to keep me company—and Jeremy, of course. The rule has always been that the time doesn’t start until it is completely dark—just a few minutes away.

“I gotta be home by midnight,” I said. “My parents went to a friend’s house.”

“Not me. Nobody’d notice I was gone,” Jeremy responded, pulling his flap cap down to cover his ears and licking his lips. “You’re lucky. Your mom’s real nice.”

“She’s got everyone fooled,” I interjected.

“What do you mean?”

“Just . . . never mind.” I sighed and watched my warm breath travel to greet the cold winter air.

Jeremy glanced away and let his legs dangle over the circular opening, jamming his hands into his coat pockets.

I noticed two dark figures approaching from the tree line. The shadows teetered back and forth as they closed in on us. “I see you brought your friend,” said the one on the left—Adam—walking slightly in front of Kurt. Jeremy was busy running the tip of his shoe along the outline of the sewer tunnel opening.

Adam and Kurt were a grade ahead of us in school.

Adam slid his backpack off his shoulder and pulled out a bottle of vodka. There was just a little missing, and he quickly twisted off the top from its long neck and pushed it into Kurt’s chest. Without hesitation, Kurt lifted the bottle, squinted his eyes, and took a swig.

“You two—so cute together,” Adam continued. “Does he drink?”

“He’s probably the oldest eighth grader. Ever,” Kurt added.

“Kurt, give him some,” Adam interrupted, and then swiped the bottle and held it out in Jeremy’s direction. Jeremy gazed at me as if looking for approval. I shook my head decisively and watched him slowly grab the bottle and raise it to his lips. He opened his mouth and swallowed but immediately spit some back out and began coughing.

“Ha-ha-ha. He even drinks funny,” said Kurt. “You would think he’d be a natural.”

“He failed third grade twice—the whole family is trash,” Adam said, continuing to chuckle.

I stared at Jeremy, watching him cough and then try and catch his breath. He took to the bottle again—again with the same result. He tried a third and fourth time, with the same outcome.

“Ha-ha-ha. Aw, man. Look at him go,” Adam interrupted. Both laughed.

The fifth time yielded a different result. He drank from the bottle, and then it slowly descended from his lips, glancing at us with a vacant expression. He sipped again without choking, setting the bottle on the cement of the sewer drain beside him.

Adam reached into his backpack and pulled out a rock. “If you can empty the entire bottle, I’ll give it to you.”

Jeremy inspected the rock, a purple amethyst. He marveled at its intricacy, at its brightness, its uniqueness.

“Now listen,” Adam interrupted, fighting back laughter. “This rock will prevent anything bad from happening to you; there’s a whole story about it—”

“What are you talking about,” Kurt interrupted.

“I can’t remember the whole story. You hold the rock close enough to your chest, you won’t get drunk. It has . . . special powers.”

Jeremy concentrated on every word pouring from Adam’s mouth.

“You’re an idiot,” said Kurt.

“Think I’m making this up?” Adam continued. “I changed my mind. You need to drink the whole bottle and spend the night inside the sewer drain—like way inside.”

Adam leaned over to Kurt and said quietly, “Don’t worry, man. There’s another bottle in the cabinet.”

Jeremy looked at me, excitedly, holding the rock in his hand. I could feel his stare burning into me, but I refused to look in his direction. I just gazed away, focusing my attention toward Adam.

“What’s it gonna be?” Adam impatiently added.

“He’ll do it. I’ll make sure,” I responded, surprising myself at the quickness of my response. “I’ll stay here. It’s almost seven now, and I don’t need to be home until midnight. He’ll never make it past midnight.”

Adam looked at me, grinning. “Alright.” He had a look of pride or satisfaction or some mixture of the two in his eyes. “Have it your way.”

“Let’s get out of here,” Kurt said, grinning and shoving Adam with his left hand.

There was no urgency in their steps. I watched them focus their attention from Jeremy and then turn to leave. I could occasionally hear an outburst of laughing or Adam emphasizing a word in conversation. They got smaller and began to blend into falling snow and darkness.

I turned back to Jeremy and noticed that he now took to the bottle with a new fierceness and determinism. After only fifteen minutes, he had drunk the bottle to the halfway mark.

“Jeremy, let’s just pour out the rest. I won’t tell them we did.”

“I want the rock,” Jeremy responded.

“Jeremy, there is nothing special about the rock. They were just messing with you.” I began to lose my patience. “Everyone does. It’s so easy.” I paused and exhaled. “The rock is just like any other rock,” I said, with a stinging frustration. “It’s nonsense. You know he’ll never let you keep it.”

He took another sip and another, clenching the rock close to his body with his right hand. “I want it. I just want it.”

Ten more minutes passed with Jeremy occasionally sipping at the bottle. I reached for the bottle and then held it in my right hand. I refused to let him drink the rest. “Please, just go in. I’ll start the timer now. An hour is enough.”

“Okay,” he said in a nasally voice.

Jeremy stammered as he got to his feet. He rested his hand on the lip of the sewer drain and then instantly began to vomit. It came violently rushing out of his swollen face.

“Jeremy, do you see? The rock, it doesn’t work,” I said. I sighed and looked in the direction of where Adam and Kurt had disappeared. “Let’s go home. They just wanted to be cruel to you.”

Jeremy dragged his sleeve across his face and looked at me with welted eyes and smiled. He mumbled, “I’ll beat your time” and turned away from me, coughing and trying to catch his breath. I watched him crouch down and crawl into the sewer drain. I clicked on my flashlight and peered at him crawling deeper and deeper until he disappeared.

I looked up and saw a starless sky tucked behind a relentless steady snowfall. The wind began to pick up with occasional gusts that rattled the branches. After two minutes of waiting, I yelled for him but received no response. I sat on top of the sewer opening and took a drink from the bottle. At this point, maybe an inch of liquid remained. I jerked back and spit the liquid out as it felt like fire when it hit the back of my throat. It was only the second time I had alcohol. I couldn’t seem to remove the hot saliva from my mouth, emitting the spit from the tip of my tongue in rapid succession.

I almost forgot—I glanced down at my watch and started the timer and yelled into the tunnel for Jeremy—again, no response.

After rubbing my hands together and lifting my shoulders to cover my face from the wind, the watch hit twenty minutes, and I reached for my flashlight. I saw nothing as the light poured into the dark circular opening. How far could he have gotten? As I surveyed the inside of the sewer drain, the wind picked up, knocking the bottle behind me on its side. The liquid trickled out—I could not care less.

I decided that I waited long enough and bent over and made my way into the opening. After crawling for about twenty seconds, I pointed the flashlight straight ahead—still nothing. I looked back and heard the whistling of the wind swirl past the opening, almost angrily. I paused to listen for Jeremy’s movement or voice. This is ridiculous, I thought. I’ll just bring him back to my house and let him sleep it off. There is no point to this nonsense.

I crawled deeper into the tunnel and stopped. Still nothing. Awkwardly hitting my elbows on the floor of the sewer drain, I dug deeper into the mouth of the drain until I could barely see the opening from which I entered. A foul smell hit my nose —followed by a flash of rapid movement. I saw it. I didn’t want to see it. I never should have gone in. I shouldn’t be here. This was a mistake. Jeremy was lying on his side, his body convulsing. I turned him toward me and saw that his eyes were half open. I panicked. The purple amethyst lay just inches in front of him, covered in his vomit. I turned around and headed back to the opening, but then faced his direction again—his convulsions seemed more violent the more I backed away. I re-approached and placed my hand on his side, feeling his unnatural movements. His eyes were glazed over and without focus. Removing my hand, I reached for the purple rock and clenched it. I began to scuttle backwards as the smell of fresh vomit rushed back into my nose and repulsed me.

My heart galloped in my throat. My breathing quickened. I moved faster. I couldn’t breathe in the tunnel. Not a single breath of air was enough. I tried filling my lungs with air but nothing worked. I felt trapped and that the opening was collapsing around me. I could see the circular opening just feet from my fingertips and reached for it, sucking in as much of the fresh air as I could.

As soon as I reached the opening, I stumbled to my feet and ran. I didn’t look back. I wouldn’t look back. I swallowed air but choked on it as I stumbled the way to my street. I can’t even remember how I arrived.

I unlocked the front door to my house and instinctively went straight to my room. All I could think about was tearing off my clothes. I ran downstairs and ripped a black trash bag from the box underneath the kitchen sink and struggled to snap it open. Thoughts of Jeremy’s face cut through every time I would blink my eyes. Once I got the bag open, I forced everything into it. Everything. Except for the rock. I placed it on the nightstand next to my bed. I was sweating but my legs were cold and my teeth were chattering. Closing my eyes for a second, I placed my shivering right hand on my forehead. The smell of vomit hit the back of my throat and a paroxysm of pain struck me violently.

Stumbling to the bathroom, I turned the knob to the shower all the way to hot and got in. The steam surrounded me and the pain of the hot water soon pelted me. I couldn’t move from the punishment—I wouldn’t move from the punishment. I began to sob—and dropped to my knees—the water slicing me on the shoulders and neck. Seconds blended into minutes until I could stand again. Reaching for a towel, I removed myself from the water and turned off the pressure and surrendered into bed. My skin ached. I looked at the purple rock on my nightstand and closed my eyes—

_________

|

Haveli

Sheikha A.

The halls around me shed their dust

like flea-motes,

I know this place of de-sewn shadows,

walking the lengths of my ancestral home

while I smell the carpets hiding

their wetting greed

rolled and stacked up, I see rooms come out

of rooms, the walls shift to the forward

shuffle

of my feet, more carpets, more dust,

more musty

shame hangs with their sons scaling

the cob

webs, the dust float like angry flies

over an empty plate

that is my body, shed of bones,

given to rituals

as the walls keep opening into rooms,

my steps

braver, my heart the one of a deer

on a stick

over a cooking fire, I know the finding of

nothing within something that is everything

and the walk becomes a more

pronounced science

the dust gathers thickly, as though by command

the walls end to a wood-latticed window –

the gates of the shadow

wherefrom it’d enter –

the road beyond a tapered racket of shops

without doors, the open faces of

which look up

telling me this is home.

* Previously published in Danse Macabre, 99

|

Symphony Tonight

Sheikha A.

The sounds of loneliness sing

through the eyes,

hear them in the slow sweeping

of oars in still waters,

the overlooking moon’s breathing

like a wolf behind a bush,

a faint whistle of a white winter

owl on a barren bough;

there is a song playing on repeat

in my head

about love’s conquers, happy

melodies in your smile,

your grim stare of a hunter’s,

the sound of wind

between your fingers as your run

them through your hair,

the drop of my heartbeat

in the lock of your look,

the shovelling of sand

under our toes as we walk,

the whimpering of foams

as the water writhes,

the gentle thumping of the pier,

you urging me towards the sea –

* Previously published in Danse Macabre, 99

|

Slain

Sheikha A.

It has become quiet

thinking up a line of soul,

there is a sparrow

outside circling the tree

at this hour of night

unusually, its feet can

barely grip the thin,

woodless twigs it has been

teetering on

much like the veins

in my body right now

running course

like a lump of entwined