A Viable Option

Jack Moody

It’s a common misconception that during free-fall, the human body will give out and go unconscious before the inevitable impact. Most often than not, you will be painfully aware of every second until the body connects with the water and crumbles, breaking every major bone, snapping the neck and spine, leaving the incapacitated victim to slowly drown in the forty degree harbor if you’re not one of the few lucky enough to simply die upon collision with the beautiful, blue death that a mere four seconds ago waited dutifully at 250 feet below you before taking the 75 mile an hour plunge into black certainty. There had been 1,600 before him since the Golden Gate Bridge’s opening in 1937, not including the handful that decided they had made a terrible mistake mid-flight and somehow survived to become paraplegics, or at the least, just as fucked up as they had always been before their ill-fated and miscalculated jump into the San Francisco Bay. That’s not to say that many of the other 1,600 dead didn’t also decide they had made a terrible mistake mid-flight, but of course they didn’t stick around to let anyone know that.

These were among the scattered thoughts floating through his head as he hung unmercilessly over the red guardrail at three in the afternoon on a Saturday, flirting with his palpable fear of heights. The cool sea air smelled of sweet salt and urban decay as it gently rocked him back and forth on his unsteady perch every time the breeze came in again. The rumbling of passing vehicles, ignorant to his pre-meditated misdeed, softly shook the thick metal underneath his feet every few moments, but he told himself he didn’t mind the attention or lack thereof; it only brought him back into focus of why he was willingly at the edge of the plank that day. He had planned on it for weeks, but it had been characteristically cloudy for a long while, and he wished to look into the sun as he did it. Truly, it was a beautiful day out, and he saw no better way to spend the afternoon.

Passersby would walk past obliviously or shoot an uncomfortable glance at him, wondering what this disheveled young man was doing in such a dangerous place, before dismissing him as if he had already been cemented into his fate. Part of him was still uncertain, and wished for nothing more than to be stopped before he resigned to his plans. His heart would jump and skip a beat with every set of eyes that made contact with his, as he secretly hoped for someone to save him from his childish decision, but none did. This only really proved to be more of a reason to do it, and with each passerby that ignored him, the fire under his ass would grow and burn with a stubborn intensity, screaming at him through the spitting flames to be cooled by the deep body of freezing water that stared back at him from below. He spit over the side and watched the wad of saliva slowly fly down into the murky depths, counting the seconds with Mississippis. It came out to more than four seconds until contact. This worried him. He had read it took four. Maybe a human body would drop faster; maybe it was just the wind.

He had tried drinking himself to death for the past two years but it was taking too long. Knives were too sharp and messy, guns were too expensive, and no doctor in his right mind would prescribe him anything that he could overdose on. He had cried wolf so many times at this point that no one took him seriously anymore. He had crashed the family car into a tree three months earlier, but survived after rolling three times into a ditch and played it off as an innocent mistake in order to avoid going to a treatment facility, and thus have to face his problems directly.

The wind was picking up and the clouds were moving overhead at a quick pace; big, fluffy cumulus clouds that perforated the perfect light blue of the sky. The sun hung overhead and lit up every scar and freckle on his pale, exposed skin with an orange glow. His eyes fixed on a colony of sea lions lying about on a dock about a half-mile out from the bridge. Two were happily barking and diving in and out of the water together near the rest of the group. A young couple walked past behind him as he watched the animals far below.

“Hey, fella!”

He turned around to meet the noise, spat out by the young man as his girlfriend hung onto his arm.

“Hey, fella! If you’re gonna do it, do it! I’m sure it’ll work out just fine!”

The young man’s girlfriend stifled an embarrassed laugh and half-seriously scolded him before hurrying him forward. “Howard, that’s not nice! Leave him alone.”

That’s it? That’s all she had to say? Did no one care about a human life anymore? Was it overpopulation, lack of empathy brought on by the anti-social, computer-age mindset, reality television? What had happened to people? This interaction proved to be incredibly embarrassing. He had expected someone, anyone to care that he was about to end his own life in broad daylight. Where was the attention he craved before his last moments? Where was the regret in that young man’s voice, in his eyes? Did he really not care? This whole plan was beginning to feel quite lackluster and anticlimactic.

He leaned back against the metal guardrail and reached into his breast pocket for his last cigarette, reached into his jeans pocket for his lighter, lit up. Well, it seemed he had all the time in the world to make his decision. He figured it would be a lot easier. Things change when you find yourself looking into its face; death’s face. He was going to do it, sure he was. He just needed to step back and breathe, get himself prepared. A car rushed by and shook the bridge underneath, knocking him off his footing momentarily. The blue Bic lighter shook loose from his hand and plummeted into the bay. Five seconds. The sea lions had all jumped into the water and swam to a different area of the harbor where he couldn’t see. White puffs of smoke disappeared into the gusts of wind overhead as he crossed his eyes to focus on the red cherry at the end of the Marlboro just below his crooked nose. He couldn’t remember how long he had been hanging on the edge of the bridge. 1,600 people, 75 miles an hour upon impact; four second drop, maybe five. He repeated the facts over and over in his head as he sucked down the last of the cigarette hanging between his lips at an angle. Okay, just do it. Listen to that asshole, just do it. You’re ready, okay, now do it. He shuffled uncertainly towards the edge of the bridge until his toes were hanging over the bay, his arms wrapped around the guardrail behind him to maintain his balance. He spit out the butt of the burnt out cigarette and took in a deep breath, closing his eyes as he took in the scent of the sweet salt air one last time. He wished he could see the sea lions. Okay, okay, one...two...three...

“Hey, whoa man! Are you crazy? What the hell are you doing?”

A sharp voice echoed inside his closed eyes as a large hand firmly grabbed onto the back of his shirt and yanked him backwards.

“Hey, are you listening? I said what in the hell are you doing?”

This caught him off guard, as he wasn’t expecting someone to so directly intervene, especially at the moment of truth. He spun around, still in the firm grasp of the unfamiliar man behind him. He was an older man, skin worn and wrinkled like thick leather. A pair of circular glasses sat at the edge of his nose, and long brown hair hung down around his shoulders in a way that he found almost feminine, but from him emanated a powerful air of unmistakable masculinity. His eyes were large and acutely aware, focused squarely on him with an urgency that for some reason struck a fear into him, causing him to feel shameful of being caught in such a compromising position.

“Well, I was planning on jumping.”

A jolt of surprise surged through his body, uncertain of why he had just been so honest with this stranger when he could have played it off like he had so many times before when he lost the nerve to follow through.

“Jumping? Now, why would you go and do that?”

The man showed no sign of anger or surprise, instead appearing to be genuinely interested why. His lips formed a crooked smile as he spoke, his eyes full of warmth. His hand still grasped firmly onto his shirt, letting him know fully well that he wasn’t going anywhere until he provided an answer. But the truth was, he didn’t have one.

“It just...seemed like a good idea.”

He immediately felt sheepish because of his lack of a decent explanation. He could have come up with something, some excuse that he had used in the past to justify his suicidal tendencies, but something about this old man clinging onto him almost lovingly made him unable to lie.

“A good idea?” The man laughed, not in a mocking way, but more so as an attempt to lighten the mood.

He couldn’t help but crack a stiff smile at the old man’s unorthodox reaction to hearing that someone was just about to kill himself. The metal underneath his feet shook as a green Sedan drove past. The man’s grip on his shirt eased up a bit.

“What did you think was gonna happen?”

After four seconds of free-fall, the human body will make impact at 75 miles an hour, shattering major bones and severing the spinal chord, leaving the incapacitated victim to drown to death in the forty-degree harbor.

“I’d go for a swim.”

The old man threw his head back and exploded with laughter. He smiled warmly and eased up on his grip.

“Right, lovely day for a swim. I was thinking about that myself. And then what?”

“And then what, what?”

“And then what, after you’re dead.”

A second couple strolled past the pair, completely ignoring their exchange at the edge of the guardrail. He paused for a moment and looked at the old man in his warm eyes.

“Well, I hadn’t really thought about it.”

The old man widened his grin.

“I suppose that would make it easier.”

“Are you gonna let go of me?”

“Hold on a minute.”

He had gotten the attention he craved so much, and he was quickly beginning to regret it. An uncomfortable wave rushed over him as his blood ran cold. He wasn’t sure why. The old man appeared to be taking some sort of pleasure out of this. He continued.

“Let’s say there’s a hell, and you end up there. What then?”

He felt a condescending tone when the old man asked that.

“Well, I guess I’d have a few questions for the devil.”

“And what if you go to God?”

“Him too.”

“What if there’s nothing at all?”

“Then I wouldn’t have any questions.”

He found it odd that the old man was yet to ask him to step back over the guardrail. He stood on the other side, nearly motionless, holding onto the front of his shirt with a firm but steadily loosening grasp.

“Do you think anything will change once you jump? For the world, for anyone else but you?” The old man asked.

“Nothing has changed from me existing in this world. I hardly doubt jumping would suddenly change much either,” he responded.

“So I ask again, why do you need to go and do a thing like this?”

“I guess it just seemed like...a viable option.”

“As opposed to what?” The old man asked again, loosening his grip rather noticeably on the younger man’s shirt.

“Sticking around. Driving a car, going to work, pretending to like people. Pretending to like myself.”

A passing minivan rumbled the guardrail and forced him to grab onto the old man’s shoulder for support.

“You know what I think?” Said the old man, as the afternoon sun shone and glinted off the top of his glasses. “I think you want attention. I think you’re scared to die.”

“I never said I wasn’t scared.”

“Then do it.”

“Let go of me.”

He was becoming increasingly frightened of this longhaired, spectral figure, and wished nothing more than to be released from his grip and take off back down the bridge where he came from. The anxiety was reaching too high of a level for him to pretend to be suicidal anymore. He was scared for his life. The old man looked directly into his eyes with growing malice and spoke with an intense growl.

“If you want to jump so badly, then jump. You’ve gotten the attention you wanted, you’ve got an audience. I’m right here. So jump...Jump.”

The old man released his grip entirely; letting him slip backwards towards the beautiful, blue death below. He screamed and grabbed onto the old man’s shirt to keep from meeting his fate. The old man lurched forward under his weight but held onto the guardrail, saving the both of them.

“Don’t let go of me! Help me up, I don’t want this, I don’t want to die!” He screamed aloud finally as he hung over the edge of the Golden Gate Bridge, barely supported by the shirt collar of the old man. There was no one on the bridge to hear his desperate pleas for mercy. He was alone again.

“You need to let go,” said the old man. “You’re tearing my shirt.”

“FUCK YOUR SHIRT!” He screamed as they struggled together on either side of the red guardrail. “I DON’T WANT TO DIE!”

“WHY?” The old man yelled back. “WHY DON’T YOU WANT TO DIE? WE ALL DO IT.”

“BECAUSE MAYBE IT’LL GET BETTER!”

Because maybe it’ll get better. This answer seemed to satisfy the old man. He smiled again and laughed softly for the both of them, reaching out his hand for the would-be jumper to finally take hold of.

“Please help me up. I want to go home.”

“Take my hand, kid.”

He let go of the old man’s shirt collar with his right hand, reached out and grabbed his outstretched open palm, then let go with his left. His hand felt like rough tree bark from a centuries-old Redwood.

“Okay, pull me up.”

The old man stood there with the would-be jumper’s shaking hand in his, smiling warmly.

“Hey! Okay, pull me up!”

The old man was silent, his long brown hair swaying in the soft ocean breeze that encompassed them so fully. He could feel the heat of the afternoon sun’s rays on his back. He took a moment to look down into the bay. The colony of sea lions had returned, and were swimming around in circles just beneath him. They were so beautiful. He turned back around to the old man.

“What are you doing? I’m ready. I’m ready.”

“I know you are,” the old man whispered into the breeze.

For a moment, life stood still. The cars passing by stopped in their paths, the birds in the air were stuck in their act of flight, the sea below ceased to undulate and flow. The sea lions waited together patiently in place. And for a moment, life was incredibly beautiful.

The old man looked into his eyes, smiled once more, and in one slick motion, released him from his grip, letting him careen down with his back to the water. The sun looked down upon him, and he looked up upon it as his body impacted with cold, blue death. The old man didn’t stay to watch; he had left the moment he let go of him. He died on impact. It took four seconds; he counted. The sea lions formed around him and they floated together. He didn’t die alone. That was the least he could have asked for.

|

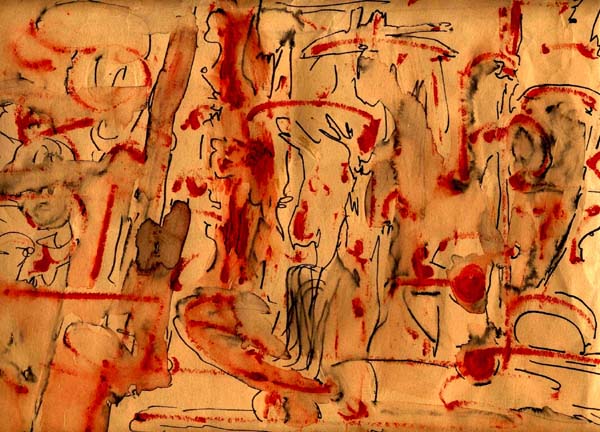

Haiku (inkblot)

Denny E. Marshall

doctor asks me what

the inkblot picture looks like

a supernova

|

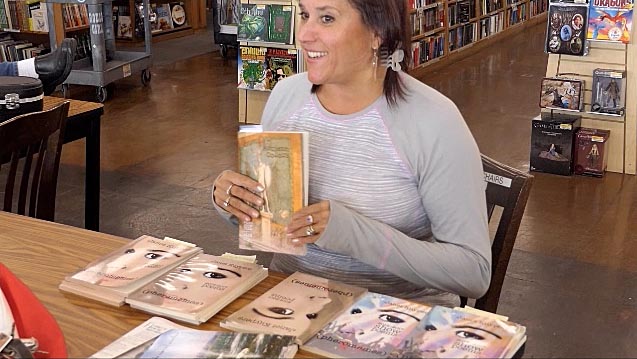

See YouTube video from 8/12/17 of John reading Denny E. Marshall’s poem “haiku (inkblot)” and Rebecca Cowgill’s poem “Rain” from “Ancient Colors” at “Poetry Aloud” open mic.

|

I Hate Monkeys

E. Martin Pedersen

Why do I, Captain Nonsense, pretend to be an alcoholic

When I’m not – because I am

Dean Martin

In my Italiano fiction

Stranger than 12-step spaghetti

Also I pretend I was locked in a closet as punishment as a child

In complete blindness, timeless, placeless

Curled up like origami – but I wasn’t

Except now I do, a different curl

Why do I need someone to say I’m so good

At what I do

When the world knows I am

As though only I know I’m faking it

Pathetic, worthless, loser

I should start a band

Called SHUT THE FUCK UP!

In why-land

Why-not land

Doubt-land’s maze of fears

Forlorn-land’s trip through the trees with mocking monkeys

One thing: I hate monkeys.

|

Malcolm X. Banjo

E. Martin Pedersen

I’m Malcolm X. Banjo, bro

I thump the hambone in the only all-black punk-funk bluegrass band in the West

All new age style Afro-grass post-apartheid world music

See I am black but was raised by white hillbillies, adopted at birth,

syncopated rated, then traded by mistake with my Caucasoid twin,

black shadow stalking

I can do the shuck and jive, I jump Jim Crow, I am Mr. Interlocutor

In the world’s only all-hemophiliac, ebony minstrel Cosby Show

Festival Medicine Man Extravaganza and Fish Fry

I don’t drink Bosco, I don’t eat Oreo

I don’t wear colors besides orange, black and chains

My motto is, “Better f-word black than n-word black!”

Minister Farakan inspires me, Hailie Selassee adores me

Michelle O and Magic Johnson taught me to sing, “Cripple Creek” or “Muleskinner Blues”

I play the comb and tissue paper with a gloved fist raised

If the white man talks to me I am courteous because I know

He’s thinking I am trying not to act Uncle Tom

And I’m thinking he has no idea of the jet-black O.J. blade tidal wave of melodic antebellum doubletime vengeance

That is right behind him ready to crash on his hideous slavedriver soul

When I play the country hit: “Color TV in the 90’s”

Ozzie Davis and Ruby Dee hug and dance for cookies and milk

Seein’ an’ feelin’ the blue heat of the riots right before they happen

SpikeLee big white hat, mirror shades, Oprah Network Nikes – hidden in plain swingin’ sight

Frail those spraypaint guns at Somali Pakistani Iraqi and East Palo Alto too

Music is my panther life, my African roots

I express my ethnic pride X-ness by playing

The five-string gourd banjo and pea green hurdy-gurdy in the world’s only n-word

All Narcoleptic

Blackgrass Rhythm Blood Donation Band and James Brown Ice Cream Social.

|

Rain

Rebecca Cowgill

rainy days

celebrate woes

of a domestic cat

|

See YouTube video from 8/12/17 of John reading Denny E. Marshall’s poem “haiku (inkblot)” and Rebecca Cowgill’s poem “Rain” from “Ancient Colors” at “Poetry Aloud” open mic.

|

Cocktails

Rebecca Cowgill

spring horizon

a line of cocktails

wash away memories

|

Meeting Head-On and Head-Off

Andrew Schenck

Sitting up in bed, my mind tried to reconcile the rapidly fading memories of a horrible nightmare with shadowy projections from a large oak tree, which crept along the moonlit walls to reach for me. Just as I made up my mind that waking up was the result of too many Doritos before bed, dull thumps began to resonate from the back porch. Moving toward the sound, a chill ran down my spine, and straight into my toes, locking me into position.

There was a hairy ape-like creature standing next to my tomato bush. He had a serious six pack. It bulged and glistened, giving me the ridiculous idea that he must be one hard-core Planet Fitness guru. His snout and cone-shaped head made me sure he wasn’t human, but he walked on two legs, giving me the eerie feeling I was looking at some kind of missing link. Like an idiot, I went for my BB pistol, thinking it was the one thing that could save my life. Just as the creature began to fiddle with the porch door, a car sped by the front of the house, casting a light directly on his face. He looked startled, as if never exposed to such a contraption, and ran off into the woods, fusing with the foliage.

Did Halloween come early this year? Have I gone completely nuts? The police certainly thought so. They took their sweet time, coming about 30 minutes after I called. When they heard what happened to me, their first question was, “Sir, are you currently on any medication?” I was starting to wonder if I did need some kind of professional help. After they left, I sat down in my chair, utterly exhausted. I drifted off, only to be woken up by the slightest rustle of the branches, the dull tick of a wall clock, the nearly imperceptible howl of a distant creature.

The next morning, sunshine streaming from my picture window washed away a lot of my anxiety. Red-breasted robins chirped and fluttered around as they always did. A white-tailed deer grazed below the forest canopy, just waiting for me to turn my back, so it could sneak into my yard and eat my rose bushes. Getting back to the day’s routine was the best way to settle my nerves. One coffee filter, two scoops of the Ethiopian blend, and three cups of water. A recipe for calm. I thought there must be some logical explanation for the creature.

Life was pretty routine until about midnight, when I heard a dull thump, followed by some kind of animal noise. It wasn’t a coyote. They have a high-pitched cry, which sounds more like a woman screaming. Instead, heaving breaths produced deep, ominous howls that ended with a crescendo of short whoops and grunts. As I peeked nervously out of my kitchen window, I saw the creature. This time, I slammed my marble countertop with a frying pan, trying to scare him off. He ran like a shot and was quickly devoured by bushes that lined the hedgerow.

Not surprisingly, officers greeted me with the same incredulous tone. After they took my statement and left, I checked, double-checked, and triple-checked all the locks before sinking into my La-Z-Boy. With a cup of hastily-made green tea in hand, I tried to process the terrifying encounter, but involuntary tremors caused my cup to quake, creating a clamor that made concentration impossible. As I slowly drifted off to sleep, a ring at the front door jolted me back to reality. Seeing a hypnotic array of red and blue lights flicker across my living room ceiling, a flood of frightening scenarios raced through my mind. I ran to the door and found a man dressed in a dark blue uniform waiting at the front step.

“I’m from the Cayuga County Sheriff’s Department,” the man said coldly. “We’ve found the suspect. He would like to talk to you.”

Talk to me? Just as I began to process what he had said, another officer led the hairy creature over to the door. He now had a bald human head, framed with coke-bottle glasses that made his eyes look squinty. It was my next-door neighbor, Paul. Where in the world...Why in the world would he buy a gorilla suit? Evidently, he got it from a second-hand store, planning to pull off the mother of all pranks.

After Paul finished telling me about his plan to joke around and then share a good laugh, he looked down dispiritedly, like a child ready for a spanking.

“Would you like to press charges?” the deputy asked me bluntly.

“Not YETI.”

|

bruised

Janet Kuypers

haiku 2/14/14

I think all feel bruised

deep down, but don’t think of it

until times like these.

|

All too Common

Liam Spencer

I was running late. The appointment was for 9:30 and traffic was a bitch. The news on the radio was frightening. Two Veterans were debating the incoming regime of Trump. His supporter repeatedly sung his praises and hopes for the strong man leader. The opponent nervously said that dividing people within the military was not good for the military, and having no foreign policy experience did not bode well. The two were thanked and wished a Happy Veteran’s Day. A new program began.

I found parking on the second level and hobbled my way to the elevator. Time was tight. I might make it.

The line to check in was long. Mostly it was older, damaged people, but there were some young faces scurrying about.

The standard questions asked in the assembly line; “Last name?” “Insurance?” “Date of Birth?”

“Next?”

I looked over the new paperwork I had just received in the mail. It was from OWCP (Office of Worker’s Comp. Programs). Federal workers’ comp. Sigh. My back. This time it was middle and lower back, along with left hip and groin. It hurt like a motherfucker.

I checked in and hobbled to the spinal clinic. I knew them well. They had more paperwork for me. All things must be tracked in every way. Mountains of trees dead for record keeping, to ensure against bad apples.

I shaded in the areas on the tiny human body inked onto the form. How absurd. Scales of one to ten. Where was thirteen? New symptoms? Not enough room to fill out. The old ones had not been fixed.

Work is such a bitch. If one is even slightly capable of physical work, they’ll be chewed up and spit out until they’re no longer capable of any work. Then it’s to the streets.

With Trump coming, the streets will mean private prison labor camps, which will mean death.

It was my turn. I was whisked away to a room, and asked questions by a cute young woman. Bubbly.

“Oh, you prefer to go by Liam? I have a son named Liam. The thing is (she giggled) it took him nearly two years to say “Liam.” He kept saying “Lia.” I told him “No No not Lia...not Lia... Your name is not Lia.”

She giggled and blushed a certain sexiness.

“Dr. Burton will be in to see you shortly.”

“Ok. Thank you.”

I went back to completing paperwork, wondering if the kid would end up changing his name to Lia, and if would be alright for him to do so by then.

Dr. Burton came in, tall and lanky as ever, his long silver hair flowing in the wind supplied by his hobbled pace. He washed his hands before shaking mine. He sat down with some paperwork just as I handed him more.

“How is it going?” he asked as he looked over the shaded body on the paper.

“Not good. I’ve had another injury.”

“Really?!”

“Yes, I sent a secure message with details and the doctor I saw.”

“Yes, I saw that.”

“Speaking of which, I have yet more paperwork to fill out. For the new injury.”

He began looking it over and sighing.

“Yeah, all the paperwork. Looks like you’re swimming in it.”

“It never stops.” He sighed.

“Well, it’s all a nightmare here too.”

“Yeah, I bet.”

“and the election didn’t help either, shit.”

He took a break from staring intensely at the paperwork, leaned back and smiled.

“So you didn’t like the results, huh?”

“I need a full roll of Charmin every day.”

“Well, Liam, you’re a white guy, so you have little to worry about...unless you try to save those who are not as white, that is.”

“You know the old saying though; First they came for.... Need I say more?”

“Liam, I don’t think....look Trump doesn’t believe what he said. He just said whatever to win. He’s....He’s just...He’s just full of shit, Ok?”

Dr. Burton looked around nervously as we both laughed. He had gotten away with one.

“Well, with this new injury, I’m required to examine you. I already know what’s going on. You’re getting a new MRI. I still have to give you an exam.”

We began. It was standard. I couldn’t quite stand straight at first, but worked my way up. Crouching only went so far. My left leg began shaking and giving out as I struggled to straighten my back. Pain was severe.

“Hmm.... I’m going to have to study you more. Have a seat on the table.”

“Uh oh...I’m not sure I like the sound of that.” I said as I sat down.

“No, there’s no uh oh. It’s very common, actually. Some damage to discs. Common.”

He began testing reflexes, etc., and sought to reassure with calming voices.

When he got to my right foot, he looked up at me sharply. It had been my left leg and foot for all this time.

“Did you ever have brain damage?”

“No.” I gave that look.

“Hmm....Ok. Make yourself comfortable while I fill out this paperwork.”

He began filling out paperwork furiously, rarely pausing. I began alternating between sitting and trying to walk it all off, while trying to peek at what he was writing.

What the hell was this? What now?

I noticed on one of the OWCP forms he had written that it was certainly a work injury. Whew! That had been a fight since the last back injury, some seven months prior. Now, that, at least, would be resolved. I would have some measure of income, even if I was not able to work until this healed.

“You’re getting an MRI on both your lower and middle back. I’m keeping you off work for at least a month, probably longer, ok?”

“Ok. That’s probably a good idea.”

“Yes, yes it is.”

“What was the thing with the right foot? Brain damage?”

“No no, what that likely means is that there’s some nerve compression in your middle back, which may explain the groin pain as well. Now, do you have numbness in your groin?”

“Well, not really...I mean, there are times where there is an absence of pain.”

“Ok. Good. If there is ever numbness, get to the ER, ok?”

“Ok.”

“Now, would you like some pills for the pain?”

“No, I still have plenty left from the ankle surgery two years ago. I hate pills, and I know they’re expired, but I ignore those expiration dates.”

“Good. Those pills are horrible for you...and you’re right, the expiration dates don’t mean anything.”

He continued filling out forms, then handed them to me, asking that I hold that bundle while he finished yet another bundle. His desk was too small to fit everything.

While he was wrapping up, I looked at the paperwork he had filled out. For the OWCP forms, he had written “No surgeries to be scheduled yet, but highly likely pending MRI results.”

Fuck! I knew the road all too well. Minor, routine, day surgery my ass! Here I go again.

Quickly the MRI was scheduled. The next appointment set. Out the door to my car. The good thing was that I wouldn’t have to go to the hell of work for a month. Whew. At least that.

The radio held more news on the incoming Trump regime, with experts of every persuasion citing the same unpredictability. Some reassurance was predictable, no matter how false it would be.

I knew it was coming. Congressional leaders and others of influence would seek to show normalcy, lulling us to relaxation about what was coming, meanwhile knowing full well that no one could stop Trump. No one could. It was truly the end of Constitutional Democracy.

It was much like when doctors tell you it is nothing to worry about. It’s very very common. Death is also very common. Authoritarianism is very common. War is very common. The fall of a great power is very common. Nothing to get upset about, right?

What is, or I guess was, uncommon is Constitutional Democracy. I thought to the founding fathers. When I got home I looked up and reread the Declaration of Independence.

The time is coming to restore the uncommon, much like being able to stand and walk when one is over a hundred years old. Give me the uncommon any time.

I paced my apartment. Who would stop Trump? How? When? Would he be stoppable? I thought about the uncommon peace in Europe; the longest in history. It would be no more. NATO and the EU were about to be further gutted, the far right taking over. The commonalities of war and brutalities returning. We’ve learned nothing from history.

A beer opened. Then another. Nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. Born in the USA.

My back locked up. My groin doubled me over. I forced deep breaths into my lungs. It released a little, just enough to grab ice packs from the freezer and make my way to the couch. My body relaxed slowly. A little of the blanket found a way to snuggle, lulling me to sleep, like the majority of the country.

Meanwhile storm clouds gather, and a new normal begins to set in. Dehumanization already well established. Building ever higher. Scapegoats number in the billions. It’s been building for a very long time. Now unstoppable, even in the mightiest nation in history.

It can’t happen here. It IS happening here.

We’re all just common after all.

|

Shotgun Signs

Justin Hunter

The movie theater played classics on Tuesdays for two bucks a pop. You had to get there before eleven, though. And they wouldn’t serve alcohol even though the goddamn bar is just as stocked in the morning as it is late at night. So, Daryl poured some coconut rum into a plastic bottle of Coke while still in the parking lot. He’d found the rum tucked in the bottom drawer of the dresser at the old motel he stayed at last night. He slid the bottle into his jeans pocket when he walked into the theater. Now, he was itching to pull it out as he waited for the 10:30 a.m. showing of The Jerk to start.

His daughter’s first movie had been in a theater like this. Small, empty, playing classics like this one. Dani laughed and he laughed and What’s Up Doc? carried them through to the black-screen credits.

That was before Daryl decided he didn’t want his daughter anymore.

An usher walked past Daryl, looking down. Suspecting. Then, he came back and stood next to Daryl. “Sir, is everything all right?”

Daryl kept his eyes on the screen, waiting for the movie. “What?”

“You don’t look well.”

“I’m not.”

“Can I do—do you need anything?”

“I need plenty.”

The lights dimmed and the usher gave up and walked away. Daryl pulled the rum and Coke back out and sipped as the movie began.

He wished he could say he was drunk when Steve Martin danced on the porch of that house at the end of the movie. But he didn’t feel a thing. He stood, knees popping, and walked out of the theater, past the concession stands, and into the parking lot where the sun had begun to bake the tar.

He stood in the middle of the road before walking to his truck, and he tried to hold the sun’s gaze. His eyes burned after a second, and his eyelids shut after two. He used to tell his daughter staring at the sun would make her go blind, but that was when Dani was just a girl. Now, he didn’t know what he’d tell her.

When Daryl got to his truck, he tossed the empty Coke bottle in the bed. The bottle of coconut rum in the glove compartment should get him through his day of driving. Johanna used to drink stuff like that. Bay Breezes made with Malibu, Hurricanes made with some other shit that tasted more like Kool-Aid than alcohol. She spent the summers sipping cocktails on the back porch, pretending it wasn’t a hundred and fifteen degrees outside.

He and Johanna were still married as far as the law was concerned. But she wasn’t going to find anyone new with the way she was, and Daryl didn’t want anyone in his life besides their daughter.

He climbed into the cab of the truck and started it up. Most days began like this now. Maybe not with a movie, but with a couple of drinks and too many memories.

Dani had been eighteen when she told them she was moving in with Sharon. Johanna told her it was a great idea, told her she supported it. And that’s why Daryl’s wife still got to see their daughter.

Daryl shut his eyes and tried to remember the exact words he’d said to Dani. “Ain’t no daughter of mine shacking up with a dyke.” That was it.

Of course, if it had stopped there, he might not be driving up and down the empty highways of Southern Arizona just to keep from going insane. No, Daryl told his daughter that she was a piece of shit. Human garbage. That if she left his and Johanna’s home, there’d be no coming back.

She left, and now all he wanted was for Dani to come back.

But there wasn’t anywhere to come back to. Daryl’d been living out of his truck and cheap motels for months since Johanna’s thing at work. Somehow, the way Daryl treated their daughter didn’t do them in. It was something that happened on the job. From what she would tell him, Johanna had to use her gun and it messed with her head.

He guided the truck onto the back road leading toward the state highway cutting west toward Tucson. Dani was living in a trailer with that same girl across the state line up in Utah. They must have wanted to escape the desert. He couldn’t blame them.

Daryl had even driven up there once or twice. Long drive. He’d sat in the bed of his truck, drinking warm beer, and watching the light through the curtains of the trailer’s windows. He couldn’t just go knock on the door. He’d tried to come back from what he’d done, but Dani wouldn’t allow it.

A cloud streaked in front of the sun, dropping Daryl into the shadows. When the cloud passed by and the sun lit the cab again, the light caught the edge of a piece of chrome on the passenger side floorboard. He leaned over and pulled back a rust-covered tarp and looked at the shotgun on the floor. The old 10-gauge wouldn’t do much in its current state, but it helped Daryl sleep at night.

Sometimes, just before laying his head back in the reclined driver’s seat of the pickup at the end of the day, Daryl would slide the barrel of the shotgun between his lips, careful not to smack it against his teeth. He’d hold his thumb across the trigger, and he’d close his eyes and think. Sometimes about Dani—like how he didn’t care who she fucked now, probably didn’t care back then either. Sometimes about Johanna—how he missed her forgiving him for everything he’d ever done as they fell into bed together.

And on these nights where Daryl let his tongue run across the cold steel shotgun barrel, he’d let his brain wander until he couldn’t stand it anymore. Then he’d pull the trigger.

The dry click of an empty chamber made his blood go cold and his skin tingle.

He’d picked up the shotgun at a gun show after he got tired of passing road signs torn apart by birdshot. If people loved shooting up metal signs on the side of the highway, he might as well give it a try. But he never got around to buying shells.

When Daryl made it to Interstate 10, he went south then caught Interstate 19 toward Mexico. He ducked off I-19 at the first state highway he could find, and he set the cruise control. Yesterday, he drove five hundred miles back and forth across Pima County, Santa Cruz County, and Cochise County. He hit a coyote in the last hour of driving, and that told him it was time to call it a night.

By one in the afternoon, Daryl was fifty miles outside the city. He passed trailers and ranches. A fireworks stand stood a few yards off the highway. When Dani was twelve, Daryl tried to impress her with a fireworks show on the Fourth in their backyard. Johanna had told him not to do it, but she was gone to work when he sat Dani in a lawn chair out back. He lit the first firework without any trouble. The second one, though, exploded on the ground, caught Daryl’s arm on fire. He got it put out with just a few burns, but Dani cried the rest of the night.

He’d take that night over any other he’d had in the last few years.

How he’d made it this long was a mystery. Dani was thirty now, had two kids she adopted. That Sharon girl—woman, now—worked at some crisis management company. Didn’t make much as far Daryl knew since they were still stuck in that trailer. But Johanna told him their daughter seemed happy.

For the first couple years after Daryl told Dani not to come back, he stayed angry. Couldn’t look at a picture of her without wanting to hit a wall. He’d shattered every picture of his daughter they had lined up on the dresser after Dani moved out.

Daryl spun off the cap on the rum, took a drink from the bottle, then closed it up. He watched a storm build to the south. All show, no go. The clouds puffed and darkened, but when it came down to action, the storm would back off. Like a bully forced to fight for the first time.

Daryl had been fighting for some time now. Fighting himself. Fighting Johanna. Fighting the pain after he got hurt on the job. He broke his back in six spots when that wall came down on him. Now, Daryl wasn’t supposed to lift anything heavier than ten pounds. He was supposed to be taking Vicodin to numb the pain. And he was living off the settlement the company gave him.

That happened four years ago. Maybe that’s what changed his mind. Made him realize what a piece of shit he was. Or maybe it was Johanna leaving him.

The first time Daryl tried to apologize to Dani, to beg her to let him back in, was three years after she left. Johanna gave him Dani’s number, and Daryl called. Sharon answered and even begged Dani to come to the phone, but Daryl heard his daughter in the background.

“I ain’t got a daddy,” she’d said to Sharon. Then the phone went dead.

Daryl tried once more after the accident at work. From his hospital bed, he scratched out a letter. Said he wasn’t worth the time she was taking to read the letter, but he hoped she could forgive him. Said he loved her. Said he might even love Sharon if Dani would give him another shot. He wrote about his own father. No excuse, he’d told her, but his own daddy hated everything. Hate flowed through blood, but Daryl should’ve been better.

When he got an envelope back from Dani, his heart about stopped. He was out of the hospital by then, laying on the couch at home. He tore it open and found his original letter shredded. He dumped the tiny pieces of paper to the floor, laid his head on the couch, and closed his eyes. He hadn’t tried to reach out since then.

Daryl passed a few trailers, some slump block homes, a gas station serving as a grocery store, and a post office. He watched the hawks high in the sky, circling, waiting. Waves of heat rose from the tar ahead of him, and he imagined the rain coming, cooling the road. He passed the shell of a burnt-out car and an old mattress tossed to the side of the road.

Then, he passed a gun store and hit the brakes.

Daryl pulled to the side of the road and looked at the store in his rearview mirror. It was looking back at him, daring him to break eye contact. He threw the truck in park and stepped out into the dusty hard clay lining the highway.

He walked back to the store and pulled open the door. An old Indian with close-cropped hair nodded then went back to watching daytime television on the black and white mounted behind the counter.

“You got 10-gauge shells?” Daryl asked.

The Indian didn’t look up, but he pointed at a wall toward the back.

Daryl looked at the rifles on racks along the wall, the handguns under the glass. He could look all day, but he wouldn’t be able to walk out with one of those guns until passing the background check, and that would take too goddamn long.

He picked up a box of 10-gauge Remingtons from the shelf along the wall in the back and walked up to the counter. It smelled like sawdust and whiskey in the shop, and it reminded Daryl of working out in the garage when Dani was little. He built her a rocking horse from wood he’d picked up in the neighborhood. She watched him, clapping when each new piece was finished. And he got that thing polished to a shine while he drank cheap booze from a styrofoam cup.

“What’re you drinking back there?”

The Indian looked up. “What?”

“Smells like something I’d drink.”

The Indian shook his head. “You’re on the reservation, so you assume we’re all drinking, all the time. That it?”

Daryl shook his head and placed the shells on the counter. “Nope, just smells like whiskey. That’s all.”

“Well, you smell like rum.”

Daryl shrugged and pointed at the box of shells. “How much?”

“I’m not selling these to you when you’re drunk.”

“I ain’t drunk.”

“Well, you’re not right either.”

Daryl shook his head. “Just sell me the damn shells.”

The Indian looked Daryl in the eyes. “Anything else you want to say to me? Maybe you want to ask me to do a rain dance for you, huh?”

Daryl thought about the storm building out to the south, and the Indian went back to watching the television. Daryl pulled out his wallet. He grabbed a twenty and laid it on the counter. “I didn’t mean no offense. This should cover the shells.”

Daryl grabbed the box, but the Indian slammed his hand down on Daryl’s hand. “Watch your mouth next time.”

Daryl nodded and slid his hand and the shells out from under the Indian’s hand. When Daryl was back outside, he opened the case of shells and looked inside as if he was worried he’d just bought an empty cardboard box. He found five rounds stacked in a line inside. Satisfied, he closed the lid and walked back to the truck.

He should have been angry. And maybe he would have been in the past. Maybe he would have been if he were still at home feeling sorry for himself. Or, maybe that old Indian made some sense.

Daryl drove on for another twenty or so miles. He drove until he stopped seeing homes. When he was surrounded by saguaros and mesquite trees and open desert, he searched for a road sign. He found a sign warning drivers that the bridge ahead would ice before the road. He couldn’t remember the last time it iced anywhere around there.

He pulled to the side of the road ten feet from the sign. Daryl lifted the shotgun to his lap, grabbed the box of shells, and climbed out of the truck. He went to the tailgate and popped it open. He slid the shotgun into the bed and set the shells on the side rail. Daryl climbed up, feeling his back try to pull apart as he did so.

He picked the shotgun back up and grabbed the shells. Up front at the cab of the truck, he laid the 10-gauge down across the roof and opened the box of shells. He’d seen Johanna clean and load her guns a million times, but she never wanted Daryl to have one of his own. That’s why he kept his daddy’s old bolt-action at the job site, tucked under a ventilation duct. Until the accident. He never did get that thing back.

When he and Johanna got married, she’d been out of the Air Force for six months. She didn’t know what to do next, and Daryl suggested she try to catch on with the sheriff’s department. And after all that time, she was still there.

Daryl loaded a round into the shotgun and held the gun across the top of the cab. He aimed for the sign in front of the truck, squinting under the late afternoon sun. He laid his finger alongside the trigger and sucked in the hot air coming off the top of the sheet metal.

When he was young, Daryl’s family had big get togethers. They didn’t have a name or a reason for them, but his grandparents had a lot of kids and those kids had kids. He could remember driving from Arizona out to New Mexico with his parents and pulling into the dirt lot of the ranch house. There’d already be six or seven other cars there, and when they’d get inside, the house would be an echo that just wouldn’t end. Laughter, shouting, cheering, crying. All of it rolled into one.

He’d taken that away from Dani. He didn’t think before he spoke, didn’t even think before he thought. Daryl squeezed the trigger.

The birdshot tore a hole in the top-left part of the sign, but he knew about half the pellets went sailing past the sign, cutting through the humid air. He looked out to the south and the storm clouds were getting darker. Getting closer. He loaded another shell.

Daryl started thinking about where he might sleep tonight. He figured he’d be best sleeping in the truck, but if the storm hit, he’d prefer a real roof over his head. He took aim at the sign again, but the stopped. He laid the shotgun on the roof of the cab and wondered what Dani would be doing right about then.

Daryl realized he didn’t even know what she did for work. Didn’t know what she did for fun. He made a decision years ago—one that he couldn’t even understand anymore. He just said things, spoke too much. Didn’t listen enough.

After a moment, Daryl slid the remaining shells from the box and tossed the box into the brush off the side of the road. He counted the three shells in his hand, rolled them back and forth. Then, he threw them to the side of the road, leaving the one chambered in the shotgun. He climbed down from the bed with the gun leaned against his shoulder.

He wondered if Dani would have come to the funeral if that wall had killed him. Probably not. He wouldn’t go to his own funeral even if they had an open bar.

Daryl climbed into the truck, laid the shotgun on the passenger side floorboard, and cranked the engine. He watched the storm swirl overhead and heard the first rumble of thunder. The storm might have a little go in it, after all.

He put the truck in gear then flipped a u-turn in the middle of the highway. It was a half-day drive up to Dani’s trailer in Utah, and he wanted to get as far away from that storm as he could.

|

Justin Hunter Bio

Justin Hunter is currently working on his MFA at Arcadia University. He lives in Dallas with his wife and kids, and when he’s not writing, Justin is probably buried under a doggie pile of children and, well, dogs. His work has been published or is forthcoming in Corvus Review, Down in the Children, Churches, and Daddies Magazine, and Centum Press, among others.

|

gone

Janet Kuypers

haiku 3/1/14

when the love is gone

I’ve searched for it, and wondered:

where did the love go?

|

Up Against the Wall, Millennial Females:

The Changing Fashion in TV Sex

Dennis Vannatta

It’s been over twenty years since Dennis Franz paraded his naked posterior on prime-time network television.1* Twenty years is not so long in historical terms, of course. Indeed, the much ballyhooed sexual revolution of the ‘60s was slow to reach television. Not many years before the hippies began letting it all hang out, Lucile Ball and Desi Arnaz, a real-life married as well as sitcom couple, were forced by the TV mores of the day to sleep in separate beds. Today, TV couples in the throes of passion don’t even bother finding a bed. But more on that later.

The increasingly realistic depiction of sexual acts on television mirrors the increasing popularity of cable TV stations. It began there, and network television followed, a bit gingerly. I refer, of course, to simulated sex on what we might call “standard” TV: the network channels, FX, AMC, TNT, and the like. Porno channels are there for those who want them. (Not me; my wife won’t let me.) Sex didn’t burst upon us in all its variety but began modestly, one might say almost demurely, and went from there. One curious aspect of this phenomenon is the way sexual activities have come in preferred styles or fashions that change over time. Once this was popular; then that; now the other. What’s next?

If the first depictions of sexual intercourse now seem timid, almost innocent, one would do well to keep Luci and Desi in mind. The cultural chasm from a married couple sleeping (and only sleeping) in separate beds to a close-up (heads and upper torsos, rarely more) of a married or unmarried couple, lips locked, moaning in ecstasy is vastly greater than that from those early, minimally erotic, depictions of sex and today’s soft-core porn. The TV movers and shakers of the ‘50s wanted us to believe that couples did not have sex; by the 1980s they wanted us to believe it was happening right before our eyes. All the rest is just details—or let’s call it fashion.

That first sex was close-focus: faces, mostly, necks, shoulders, maybe the bed sheet slipping down far enough to reveal the tops of the woman’s breasts. Nipples? Definitely not. We were religious folks back then, too; the missionary position was our fashion. Man on top, woman on the bottom, just like the Good Lord intended. But was that actually sex they were supposed to be having? We saw so little of what they were doing under the bed sheet that it was hard to tell. Whatever erotic feeling was communicated—and it wasn’t much—came almost entirely through their facial expressions, their sounds. But even their sounds came in a rather narrow range: murmurs, at the most deep-throated moans. No sweaty-faced panting. Dirty talk? Don’t be silly. Orgasmic scream? Mon dieu, non!2*

It would seem logical that if “conventional” sex (missionary), suggested more than acted out, represents the first stage of TV simulated sex, then the next stage would be missionary sex portrayed more completely and realistically. Interestingly enough, though, missionary sex has never been much in vogue on television. I’m certainly not saying that we never see man-on-top, full-view (head-to-toe) sex being simulated, but given that the position, I would assume, is the most commonly practiced in actuality, it’s curious that we see so relatively little of it on TV. When we do see it, it’s almost always side-viewed, rarely full length from the top. Even today the focus tends to be on the faces and upper torsos of the partners or, in an interesting variation, on the caves, ankles, and feet, the man’s between the woman’s, toes digging for purchase against the rumpled sheet.

Why so little fully depicted missionary sex? I’ll offer two theories. One is economic. Coming so late to the sexual revolution, in competition for the entertainment dollar not only with movies, which had been doing so much more for so much longer, but also with other channels and networks, TV fashioners were soon impatient with the conventional stuff and raised the sexual ante. Missionary sex was old hat. Old hat doesn’t sell.

My other theory is offered half in jest—but only half. Now, I enjoy sex as much as the next guy, and I’m not totally immune to the charm of watching comely actors and actresses engaged in simulating it. But is it just me, or is missionary sex a little, well, ungainly. A bit awkward-looking. Unless the man is gentleman enough to support at least part of his weight on his arms, the poor woman looks like she’d have trouble breathing. If he does support himself, it looks more like a workout for him than a love session. More PT, drill sergeant! In fact, I’m convinced that the reason directors almost never shoot missionary sex from above (or, egad, from behind) is that it’s not at all erotic; it’s comical.

*

The truly erotic entered our TV virtual world when the missionary position gave way to female-superior sex. For cinematic purposes, it possesses almost every advantaged over the missionary position. Depending upon how the participants arrange themselves, the camera can close in on both faces together or either separately (difficult to do with the missionary position). Whereas the side view is the camera angle most often employed for the missionary position, the female-superior can be fetchingly filmed from side, front, back, or above. And one thing it never is is awkward or comical. Whereas the male superior partner tends to go at his task with all the elegance of a jackhammer, when the woman is in charge, she has her way slowly, gracefully, sensuously. (If she wants. She can turn up the heat, too, but her rhythms always seem attuned to the musical rather than the male’s mechanical. And, really, which would you rather watch?)

It is tempting at this point to wax political and theorize that the ascendancy of the female-superior position on TV reflects the feminist consciousness that began to change society in the 1960’s and only intensified in the ‘70s and ‘80s—precisely when the female-superior position began to dominate sex simulation on TV. Were writers and directors making deliberate political “statements” in their sex scenes? Probably most of them would laugh at the notion. Still, there it is in front of us in living color: she’s on top, in charge, going just as fast or slowly as she wants, and we only have eyes for her. Half the time we don’t even see the man, who is only a tool for her pleasure.

If this view is true, then we should expect male viewers to be turning off their sets all over America in protest, right? Ha. “Use me, baby, use me!” we shameless males shout. Indeed, as the camera focuses on the woman writhing in pleasure atop the man, who in the audience is getting more turned on? I wouldn’t hazard a guess as to whether more men prefer to be on the top or bottom during actual sex, but I’d bet a lot of money on more men preferring to watch female-superior sex.

Maybe we should just say that with female-superior simulation, TV can have it both ways: feminists can enjoy the idea of the woman being in charge while the man can enjoy those lovely vistas when seen, or imagined, from below.

*

If the triumph of the female-superior position (dating can’t be precise but let’s say over the last couple decades of the twentieth century) is in part at least emblematic of Woman’s assertion of her independence and power, the next new fashion might be seen as The Revenge of the Male. I refer to—let’s see, is there a polite term for this?—“doggy style.” Rear entry. Woman on her hands and knees, if not draped across a sofa back or table, man upright behind her, hands on her hips or waist pulling her to him as he . . . well, you know. As with all intercourse positions, this one comes with variations, depending upon what furniture is available.

The first time I saw rear-entry sex, TV version, was, I’d guess, around 2000. I do not now recall the series although of course it was on a cable channel. I don’t recall all the particulars, either, but those I do are significant. A black man is carrying on a conversation with a white man. The black man, a criminal of some sort, is menacing, and the white man is appropriately intimidated, as he should be because he owes the black man money and has been unable to pay. Indeed, the black man is having a lot more fun in the scene because as he talks to the delinquent debtor, he’s in bed having rear-entry sex with a woman. The black man tells him, Pay up or I’m going to be doing this to your wife.

Again, the specifics. The black man threatens not rape in general but rear-entry rape. That old lamentable male chauvinist canard—that if a woman is bound to be raped, she might as well relax and enjoy it—clearly does not apply here. The threatened rape is going to be even more excruciating for wife and husband because it’s the rear-entry variety. The atmosphere of the scene is one of violence, intimidation, power imposed—this despite the fact that for all we know, the woman in the scene may well be a willing participant. She hardly counts at all, though. (My memory could be faulty here, but I don’t recall even seeing her face—just as the male has as a difficult time seeing his partner’s face in this position.) Does she enjoy it? Hate it? Is she in love with her partner? Paid for sex? Forced into it? We don’t know and don’t really care. The emotions in the scene are entirely the males’—the black man’s sadistic, gleeful imposition of will, the husband’s feeling of helplessness and dread, heightened by our conjuring up his conjuring up the same scene except with his wife on the bed on her hands and knees. It’s a man’s world here, baby.3 *

Rear-entry sex has never dominated the airwaves to the degree that the female-superior position did for a number of years. It’s never been a staple of network TV, for instance, where it’s sometimes coyly referred to but rarely simulated. Still, I think it’s interesting that we’re seen it a lot on cable TV in the last decade or so. The question is, why?

I doubt if politics has much to do with it. Whereas I truly believe that the rise of feminist consciousness plays at least some part in the ascendancy of the female-superior position on TV, I was mostly being facetious when I spoke earlier of The Revenge of the Male. No, I suspect that it has to do with a more predictable motivation: ratings. We won’t go out of our way to watch a program that promises just more of the same old thing. If, on the other hand . . . Omygod, can you believe they’re showing them doing that? . . . we’ll watch, all right. The problem with this strategy is the genetic flaw in the new: it will very soon become old. It seems to me that I’ve seen less rear-entry sex on TV in the last couple of years. Has anything come along to take its place?

*

In the opening episode (“Power”) of the recent Spike TV three-part series, Tut, the pharaoh’s wife is talking to her lover in an otherwise deserted hallway of the palace. Words give way to yearning glances; glances give way to an embrace, kisses. “Look out!” I say to my wife. “I hope they built walls strong back then.” Sure enough, the man backs the woman against the wall and, Wham bam, thank you, ma’am.

Yes, trending now on your television screen is up-against-the-wall sex. I don’t claim that we see it to the exclusion of others. Rear-entry still has its adherents. Female-superior is still popular. The missionary position is still grudgingly indulged in. But up-against-the-wall sex appears with surprising and puzzling frequency. I mean, it can’t be that comfortable for the woman to be slammed against bricks, stone, wood-paneling, or drywall with shoulder-blade-cracking violence.4* For the man, it just looks like way too much work. Generally filmed from the side and slightly behind with the woman’s face in full view, the man reaches down with his right hand and pulls the woman’s left leg up and holds her in place by her thigh. Or, requiring an even greater expenditure of energy, he lifts both her legs up and holds her to him as he pins her to the wall. Not infrequently, they don’t even make it to a wall but do the humpty-dance right there in the middle of the room. Keep that up, fella, and you’re in for a lifetime of chronic lower back pain.

Haven’t they heard of beds?

I suppose what the writers/directors are trying to suggest is that the couple’s passion is so great they can’t wait the extra five seconds it would take to find the bedroom. So be it, but, while I haven’t looked into The Kinsey Report for awhile, I can’t imagine that up-against-the-wall sex has ever been very popular and I’ll wager today is far less practiced in reality than simulated on TV. Maybe I’m naïve.

Maybe I’m also cynical because the only explanation I can think of for the recent prevalence of up-against-the-wall sex on TV is, once again, ratings. You have to keep up with your competition; even better than keeping up is going them one better. Up-against-the-wall sex is better only in the sense that it is newer than the aforementioned varieties in terms of TV exposure. But the newer has a short shelf-life. Time for something different. What might that be?

*

Oral sex? It’s been going on quite a while now on TV although generally rather tamely presented, more suggested than graphically simulated. The couple will be in bed, embracing, kissing, close-up on their faces. Then we see the man begin to work his way downward until he gets somewhere mid-torso, at which point the head descend on until it’s out of camera range. In a moment his partner might arch her back and moan in ecstasy, but it’s up to our imaginations to supply the details of what’s transpiring down there. Or, switch the sexes, the woman going down—same result. Oral sex on TV, then, tends to be just about as graphic as simulated missionary sex was when we first began to encounter it decades ago: focus primarily on the faces and upper torsos, the rest only suggested.

There are exceptions, of course. In an episode of The Wire, Mayor Royce is blundered upon in his office as his secretary is taking dictation, as it were, on her knees. She springs back, and for an instant his penis is there for us to see in all its engorged glory (whether the actor’s actual member or a mock-up, I couldn’t say). Unless I’ve missed it (and if so tell me where it is so I can see for myself, purely for research purposes, of course), cunnilingus is never simulated as graphically as fellatio is in that <>IThe Wire episode. Indeed, the most famous instance of cunnilingus on TV may well be where that particular sex act is not present for viewing at all, nor even directed mentioned, but is only hinted at. I refer to the Seinfeld episode (“The Rye,” 1996) where Elaine’s fastidious, jazz-musician boyfriend finally decides to go that extra mile for her. (I use coy terms here because that’s exactly how it’s communicated in the episode; nothing is stated explicitly, nothing at all shown.) He goes to it with a will, indefatigably, but can’t quite ring that bell. Worse, when he attempts to play the saxophone before an important music producer later than day, he hits all the wrong notes, and we know why. It’s a priceless episode, hilarious, and just about as erotic as a whoopee cushion.

No, TV oral sex is too old to be new and just isn’t handled very well on the small screen. We’ll have to look elsewhere for the next new thing.

*

For the next big trend, surely the smart money would be on gay sex, especially in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decision allowing for marriage between homosexuals. I don’t mean to imply that we haven’t already seen gay sex simulated on TV, but it’s seen less frequently than one might expect and has generally been rather tamely presented: close focus on faces, men kissing men, women kissing women. Not much else. Perhaps since oral sex is such an important facet of gay sex, we shouldn’t expect to see gay simulated sex arrive as a dominant trend until TV learns to deal more fully and imaginatively with oral sex than has heretofore been the case, at least from what I’ve seen.

Since TV has indulged in the representation of rear-entry sex frequently enough that I’ve nominated it as a one-time New Big Trend, it’s puzzling that we so rarely see this variety in simulated sex between gay men. I can only conclude, if my own viewing experience is a reasonably accurate gauge of what appears on TV, that the issue is the homosexuality and not the difficulty of finding a way to present it on the small screen. I predict that this will change, though, and that there will soon be a Golden Age of simulated gay sex on TV; but it will be brief, after which gay sex will be portrayed only whenever it’s appropriate to the story. Just as, in an ideal TV world, sex in all its variations would appear.

*

Well, though, sex in all its variations? Sex with animals, for instance? I recall some comedy sketch (Saturday Night Live, perhaps?) from several years ago that offered a man and his paramour, a sheep. No sex simulation was involved, thankfully. I don’t recall seeing sex with animals more than jokingly alluded to on TV. Maybe I’ve just been lucky. No, sex with animals will never be a Big Thing on TV.

Sex with children? No. We’re not going there. Pull the plug first.

If we’re thinking about future trends, how about sex with machines (robots). It’s already been done on the AMC series, Humans. In the first instance, a comely robot hides from pursuers by working in a robot brothel. She is one of a group of robots humanized by their maker to a greater degree than allowed by the authorities, who are hunting them done. Her humanity, in fact, takes the form of a decidedly feminist orientation. The first time we see her servicing a customer, she’s being subjected to rear-entry sex. During the act she stares at the camera (at us) with eyes devoid of life, suggesting that for the woman rear-entry sex is dehumanizing, deadening. The next man who demands a dehumanizing act gets what radical feminists might say is just what he deserves: death at her hands. It’s an interesting thematic take on sex, but I have to say that man-robot sex is erotic only to the degree that the robot seems human, not a robot. I live in the South and can tell you that Southern boys love their pickups, but I’ve never heard of one having sex with his Ford 150. Man-machine sex a trend? Hardly.

What’s left? You might now be saying, Oh, you callow lad. Man on top, woman on top, rear-entry, standing, oral—you think these are the only possibilities? Well, sure, we could go through the Kama Sutra page by page, position by position, and speculate on the likelihood of one or more showing up on the flat screen. But surely these would just be variations on the old, neither singly nor in toto likely to constitute some new trend.

Similarly, we can safely predict (unless the Tea Partyers truly do take over) more nudity (full frontal on network TV), more graphic simulation of gay and oral sex. But would these manifest something new or just refinements of the old?

I find myself perilously close to the position of the head of the US Patent Office who supposedly suggested in 1875 that they close the office because “there is nothing left to invent.”5* In regard to sex, though, the truth is there are only so many things the human anatomy can be required to do in the bedroom (or on the kitchen table, up against the wall, etc.), and TV has already simulated a lot of them. Once we get all those variations and refinements, then what? Go back to the beginning? (“Honey, come quick, look at this! You’re not going to believe it, they’re showing this couple having sex, and the man is on top of the woman!”) Or maybe go farther back than that, even, to that much ballyhooed Golden Age of Television on the ‘50s when husbands and wives slept in separate beds and—hubba hubba!—blew kisses to one another.

If that happens, I’m clutching my twenty-dollar bill in my sweaty palm and heading back to the movies.

* NYPD Blue, “The Final Adjustment,” 1994. This wasn’t the first instance of primetime semi-nudity, but it was perhaps the most widely publicized and in some unaccountable way seemed the most ground-breaking. Maybe the feeling was that if they’d show Dennis Franz’s bare bottom on the air, they’d show anything.

* By the time this hardly more than implied sex had reached the airwaves, Marlon Brando had long since brought the butter to his date in The Last Tango in Paris and Joe Buck had been gone down on by a teenage boy in Oscar-winning Midnight Cowboy. Isn’t it curious that what we’ve been allowed to watch in the privacy of our homes has been far more rigidly circumscribed that what we could view in public at our local cinema?

* Here as everywhere throughout this essay, I generalize. Rear-entry sex isn’t always portrayed as violent, the woman the helpless object of the male’s will. Occasionally, the act is viewed from the front, the woman’s face dominating the screen, and sometimes, especially more recently, she seems to be enjoying herself, a most willing participant. Even so, I’d argue that the “architecture” of the act bespeaks male dominance.

* Although these collisions of woman’s back with wall can indeed be violent, we almost never, at least from what I’ve seen, get the impression of the woman being subjected to something by a brutal male, as is often the case with rear-entry sex. In all the instances I can recall, the woman was an enthusiastic participant.

* Frequently quoted but apparently an urban legend.

|

A Manageable Condition

Ruy Arango

The man sitting next to her is encroaching on her seat. He’s big. Maybe he can’t help it, but still. She doesn’t want to be touched in any way. Ever. She has the sudden impulse to tell him, to get something out of this. Sudden disclosure right in his ear.

He gets off at the next stop.

She watches him check his phone on the platform. The train moves and he slides past. She presses her face against the glass for a better angle. Little black zigzags shoot from her eyes. If people could see them they’d edge away.

The desire to lash out is healthy, her therapist told her last session. His legs were crossed. She could see his nice socks. The way he said the word healthy bothered her.

She didn’t need the help. In the first grade another girl told her dogs were stupid. It was during lunch. At hand was one of those hard shell ice packs.

It took two teachers to drag her off. When her parents picked her up the principle asked them if either of them had seen Quest for Fire. They had. The principle told them it was like that.

She gets up before her stop. Across the closed doors in sharpie:

FUCK

YOOO

Open:

FU CK

YO OO

At work they gave her two weeks off, paid. As much time as you need, some guy told her afterwards. She found out later it was the CEO.

She stomps up the escalator. The pill bottles in her purse shake like a couple of maracas. The family in front of her look back at the sound. Passing on the left, she snaps.

Outside it’s still warm and sticky. The fall is years away.

The therapist told her this could be very isolating. He wanted to know if she had people to confide in. The noise maker was set to ocean.

Steven, she said.

He made a practiced face.

Steven makes sense, he said.

HIV. People keep saying that. She finds she hates the word. It’s like The N Word, twice the work.

People don’t blurt things out or get angry around her anymore either. It’s like being held in oven mitts.

Her mother tried to move down to help out.

Just what do you think you’re going to be able to do here, she asked.

Steven was looking at her when she put the phone down, hitting her with the thousand year old wisdom eyes.

Don’t, she said.

Hope is supposed to be a part of it. Hope gets big play.

Her doctor was young and gave the impression of having spent a lot of time studying her case. He told her he would do his best.

The thing is to get ahead of it, he said. This meant two separate Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors and one Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor. Later, there might be switch ups.

Sounds like a party, she said, feet dangling from the patient table.

He told her they’d have to keep in touch about side effects.

It had been Ziagen (yellow oblong, scored), Combivir (white oblong, scored) and Sustiva (yellow oblong, smooth) to start with. The Sustiva looked like a multivitamin.

Her hair is down and already the heat is making her sweat. She used to wear it up to accentuate her cheek bones, but she’s had it down ever since she started accumulating fat on the back of her neck (Combivir).

Street level and college students in blue shirts try to catch her coming out of the station. She’s all stomping heels and swinging bag and they retreat.

She laughed when she started getting mailers for support groups. They were on high quality paper with good looking people smiling on the front. She got halfway through the first one before she could figure out what the hell they were alluding to. After she threw the thing away she realized it had been someone’s job was to make it. Another person’s job to mail them. A department ran payroll. My sickness is an industry, she told the garbage can.

Everything changes when you’re dying. Someone told her that, but who? She can’t remember. Someone well meaning.

She thinks about that as she walks through construction tunnels. Workers clomp on the plywood over her head. Thinking you’re going to die, that’s how she felt before, she decides. Now she knows, though really, something could get her before. Bus, Rottweiler, Rapist-murderer (joke’s on him!).

She shoulders through the crowd to stop with her toes on the edge of the crosswalk. Passing cars do things to her hair.

What has she been doing with her time? Not much, she goes to the therapist and takes her meds. She drinks more than she did before, but that’s not saying much. She’s not planning to go back to work. She’s tempted to take out a big loan, get a new car on credit, wrap it around a streetlamp, do something that flies in the face of her borrowed time. She knows one thing, but feels another.

Past the construction tunnel the roll away doors of a CrossFit studio are up. Blaring music and gleaming torsos. A coach asks for one more rep. Dead anyway, she thinks. Dead anyway has become her go-to against the pressures of a previous life.

Save up to buy a condo? Dead anyway.

Eat kale? Dead anyway.

Maintain relationships with your fellow humans, encouraging them in their struggles and listening in their dark moments, thus creating that succor which is the one and only comfort of this mortal coil? Dead anyway. Dead anyway. Dead anyway.

Sweat has plastered her hair to the fatty lump on the back of her neck. All around her the city is folded in on itself, the sights and sounds squared to infinity. The beggars and the buildings. The buying and selling and saving.

At the steps to her brownstone a coffee cup sits half full, she tips it over with the toe of her shoe.

I feel as if you don’t like me, the therapist said with ten minutes left. She got the feeling the therapist assumed this was how long the conversation would take.

It’s okay if you don’t, he clarified, you could even hate me. She looked at him, smooth hands, full head of hair, glasses with no smudges, and those little things. What were they called? Cuff links.

He cocked his head when she looked up.

It’s four flights of stairs to her walk up. After the first flight the sweating doubles down, then the nausea. Not fair, says some part of her brain. Not fair.

She’s got to stop at the top of the third flight to catch her breath. The nausea is like waves at a beach, crashing into her. But she’s close, close to the top. Close to home. And already she can hear Steven, who’s been thinking about her all day.

Through the door she can hear him jumping and prancing, skittering on the wood floor and he can’t wait to see her. He’s going nuts.

|

Eleanor Leonne Bennett Bio (20150720)

Eleanor Leonne Bennett is an internationally award winning artist of almost fifty awards. She was the CIWEM Young Environmental Photographer of the Year in 2013. Eleanor’s photography has been published in British Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Her work has been displayed around the world consistently for six years since the age of thirteen. This year (2015) she has done the anthology cover for the incredibly popular Austin International Poetry Festival. She is also featured in Schiffer’s “Contemporary Wildlife Art” published this Spring. She is an art editor for multiple international publications.

www.eleanorleonnebennett.com

|

Sunday School

Tyler Wolfe

God’s fingers pierced through stained glass windows, lining the walls of the cathedral. Open corridors encompassed rows of cheap, wooden benches. Archways, supported by obelisks, lined the side of those corridors, welcoming all to enter. Mice skittered about, to and fro, racing across the cathedral’s stone floor. And lastly, a massive, glorious dome rested above a crucified Jesus of Nazareth, and the Bishops chair.

It was Sunday, and Little Timmy was in trouble. He stood in the Bishop’s office, bent over, gripping the side of the Bishop’s desk as Mother Susan spanked him. He locked eyes with the carpet, which was as red as his hiney. His pants and underwear were kissing it, leaving his bottom unprotected. Where his hands gripped the desk were two worn-out edges. They dipped deep into the desk. Everyone knows where to place their hands now.